«Biochar is the ethical form of charcoal – ethical because you’re not cutting down the forest» – a green weapon in the Anthropocene age we live in

Biochar: a byproduct of Terra Preta de Indio soils

An anthropogenic dark earth mainly found in the region of central Amazon. The origins of biochar are unknown but it is presumed that for thousands of years these rich and highly fertile soils were used by ancient communities for traditional and effective soil management. The dark-colored ground contains a high amount of char, which gives it high fertility and nutrient retention. Biochar is created with a process called pyrolysis, a thermal decomposition of organic material, through toasting the biomass. Using renewable agricultural and forest waste, this process can turn any vegetal biomass into high-quality biochar. In 2002, Pro-Natura’s pyrolysis machine called CarboChar was awarded 1st Prize by the Altran Foundation for technological innovation, and since then the technology is in its 8th generation, being constantly updated and enhanced.

Since 1985 Pro-Natura created the world’s largest carbon sink, by planting over two million trees in the Juruena region of the Brazilian Amazon in partnership with France’s National Forestry Office; organized thirteen large expeditions to collect half a million samples of life forms; designed and executed reforestation projects in sixty-three countries, including Ghana, Tanzania, Brazil and Nigeria, implementing innovative carbon sequestration strategies and providing long-term food and water security, as well as sustainable employment within the local communities. Crespi has been involved in the development of a soil fertilization technology, advancing an ancient indigenous ‘dark earth’ into what is known today as biochar.

An ethical form of charcoal: biochar

«Biochar is the ethical form of charcoal, which is one way of defining it. It’s ethical because you’re not cutting down the forest», Crespi explains, continuing to clarify how it actually works. ‘In one end you put in the biomass, it then heats it, but doesn’t burn it, which is the main point and out of the other end comes out black powder, which, when compressed becomes the green charcoal – biochar. Our machines are clean, they do not emit any gas».

He points out that the machine can self-sufficiently produce electricity and biochar at the same time, alleviating the pressure of high cost of electricity in developing countries. This offers an opportunity to bring the machines to the areas of need all around the world, without having to transport large amounts of biomass through great distances. All kinds of matter can be utilized – from bamboo to sugar cane waste, rice husks, even the trunks of trees that are being felled by invasive insects. This technology both eliminates agricultural waste which has no use and would otherwise be burnt, harming the environment more; and produces ecological and fertile charcoal, which doesn’t involve cutting trees.

Lampoon talking with Brand Crespi

Forests cover thirty-one percent of the land area of our planet, counting around three trillion trees. Apart from purifying the air we breathe and water we drink, forests play a crucial role in mitigating climate change. Not only acting as a carbon sink, soaking up carbon dioxide, but they are also home to much of the world’ biodiversity and wildlife. The Amazon rainforest alone is responsible for 180 billion tons of carbon. Deforestation doesn’t seem to be slowing down, with 18.7 million acres of forests lost annually, mainly as a result of agricultural practices.

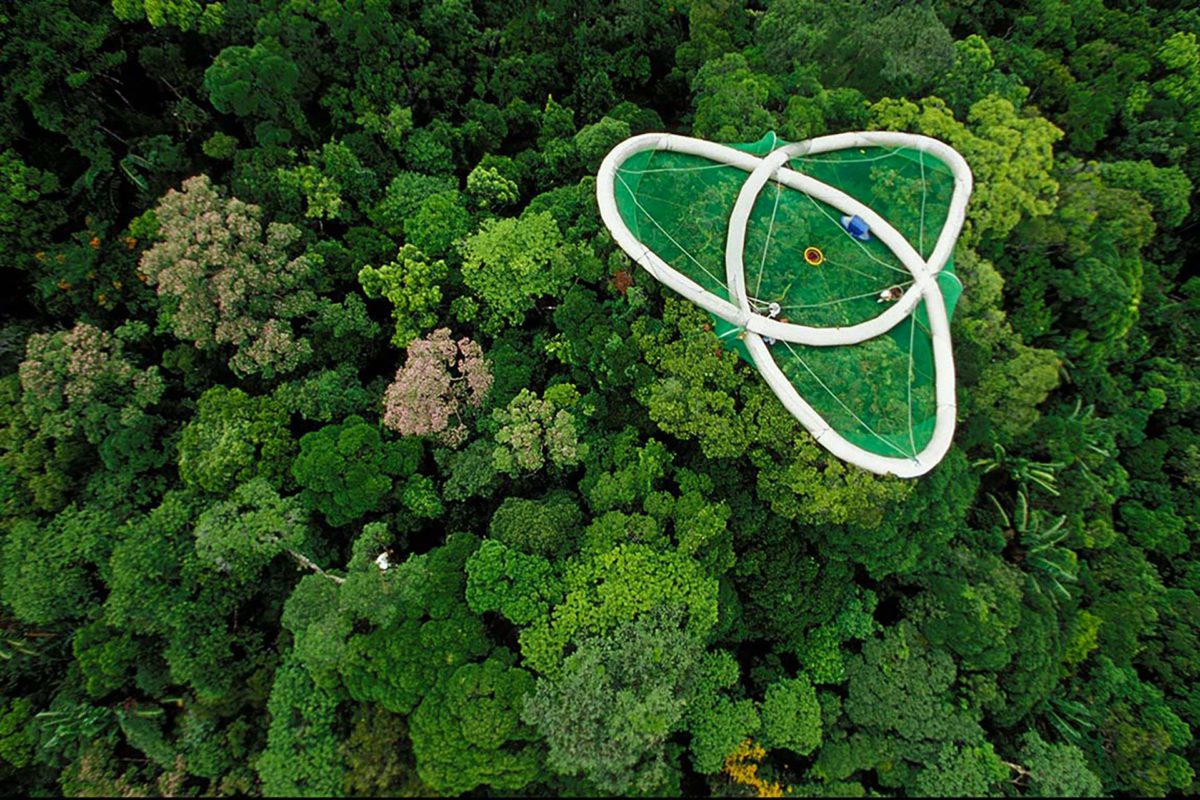

It accelerated despite a declaration on forests was signed in New York during a UN summit in 2014, requiring countries to halve deforestation by 2020 and restore 150m hectares of deforested or degraded forest land. «We need to use nature to help us in mitigating the devastating effects of the anthropocene age that we live in. To do that you need healthy forests. Forests also address water and food shortages, as well as biodiversity issues. A lot of native people traditionally used something called agroforestry which we are very much integrating into our strategies, which is to grow food in the forest canopy».

The effects of charcoal production in Africa

Crespi was first confronted with the effects of charcoal production in Africa, where seventy percent of deforestation is caused by charcoal business, as well as contributing to the air pollution, causing health problems within the local population. After investing five million euros to develop the technology, they gave some of the biochar to a neighboring farm, only to see that their rice production has doubled, and maze production has tripled in the aftermath of adding a small amount to the soil.

After years of implementation, it has been proven that just one application increases crop productivity to levels that range from fifty to 200% and maintains long-term fertility, at the same time enhancing carbon sequestration in the soil and fighting climate change. «Today we realize that biochar has lots of other applications including animal feed, which increases animal health; you can also use in the construction, add to cement to create stronger structures. And every time you use a ton of biochar you are sequestering 2.7 tons of CO2».

The use of biochar in providing food security and employment

By multiplying crops and improving soil health, the use of biochar can greatly contribute to providing food security and employment to impoverished communities all around the world. Crespi gives an example of a project in an area around the Sahara desert, where adding biochar, camel manure and water (10-15% than normally) to a sixty square meter super-vegetable garden can feed a family of ten. «We work with local communities to produce biochar based on their waste and integrate biochar into a number of what are known as climate smart, agro-ecological techniques».

He is optimistic about the future of our planet and his work – Crespi shrugs and says, «If fully implemented, we can offset up to something between 20-30% of all greenhouse emissions. It needs full global awareness, cutting down on fossil fuels and other areas and addressing food security and wellbeing of people». He is currently launching a new project in West Africa, with a goal, over twenty years to sequester 600 million tonnes of CO2 and triple the income of ten million families.

High-tech – artificial intelligence, drones, blockchain

Realizing it sounds ambitious, he is determined that it can be done. High-tech is one of the tools which Crespi is especially enthusiastic to bring into play, including artificial intelligence, drones, blockchain and satellite sensors. Blockchain can be fundamental in creating transparency and ethical practices, as well as by eliminating the intermediaries between the farms and the buyers, ensuring that the farmers are paid fairly. «I have a lot of optimism about the potential but a lot of concern about how it’s implemented. There is an enormous opportunity to use these technologies in a humanistic context».

We are still not moving fast enough to improve the situation, and simply planting more trees is not going to cut it. Biochar is thought to be the ‘Third Green Revolution’ by some, somewhat confirmed by James Lovelock, scientist and author of the Gaia hypothesis. He wrote in The Guardian, «We don’t need plantations or crops planted for biochar, what we need is a charcoal maker on every farm so the farmer can turn his waste into carbon. Charcoal making might even work instead of landfill for waste paper and plastic».

The need for older generations to embrace radical changes

Whilst there has been doubts concerning biochar, Crespi acknowledges that people and industries have always been resistant to change, but he figures that the COVID-19 pandemic might be a much needed nudge towards global awareness. «Will the older generation give up its power and embrace radical change? Are we going to go back to the systems we know don’t work, because these financial and political interests want to maintain them, or are we going to move forward into the 21st century and start healing all the damage we brought to our ecosystem?»

In 1997 Pro-Natura’s methodology was awarded the Mitchell Prize, considered sustainability’s Nobel, recognizing its proficiency in sustainable development benefiting communities in tropical forest zones. By promoting sustainable agroforestry, social justice and equality, as well as ensuring long-term solutions, this sustainable development model is now used widely around the world.

Partnering with institutions such as International Finance Corporation

Crespi says that the technique in the beginning of each project is an open conversation, including all members of the community and empowering everyone. «It always starts from understanding what the community’s needs are, then finding who the natural leaders of the communities are, and giving a voice to the women, who in majority of the cases do all the work», he says. After achieving the gender balance and identifying how their practices may be useful in a particular place, the technology and funding are brought in.

«By bringing what we call blended finance which is impact philanthropy and impact investing we can not only help communities get out of poverty by tripling income but we can also pay back investors who support this and make it profitable». In partnering with institutions such as International Finance Corporation, the investment arm of the World Bank, Pro-Natura is exploring how big players can integrate a much more just and ecological development model in parallel with their investment strategy, and pave the way for others.

«Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the mind – this is my mantra», Brando Crespi, co-founder of Pro-Natura, says quoting an Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci. He has been working in the environmental and anthropological sectors for the past thirty-five years, pioneering sustainability practices in more than 63 countries and improving the livelihood of nearly seven million people.

Pro-Natura

Pro-Natura is an international non-profit organization, originating in Brazil in 1985. Its main activity is in rural development, biodiversity protection and climate change prevention. Born in Lausanne, Switzerland, raised in Rome and educated in Switzerland, the UK and the US, Crespi became involved with Pro-Natura after building a successful career in the fashion industry, consulting multinational companies, including Ermenegildo Zegna, L’Oreal and Giorgio Armani.