Aedicola Lambrate, reclaiming Milano: a micro-publisher to help the city

Aedicola is an independent newsstand and micro-publisher fostering print culture, civic engagement, and community life in a rapidly transforming Milan

The newsstand as a space of cultural resistance in the face of gentrification and real estate pressure

GDM: Where did the idea for the newsstand project come from, and what past experiences led you to buy and reopen it?

AB: In the 1990s, I squatted in the former Zara cinema at Via Garigliano 10, in Milan’s Isola neighborhood—then a historically working-class district in the city center. We transformed the space into a multifunctional cultural center that included a restaurant, bar, and an art area with a strong focus on publishing and cinema. That experience catalyzed a small but powerful creative community. Over time, this cultural ferment began to attract attention. Bars, vintage boutiques, and new businesses opened, activating a process of urban transformation: vacant properties were repurposed, and the neighborhood started to shift.

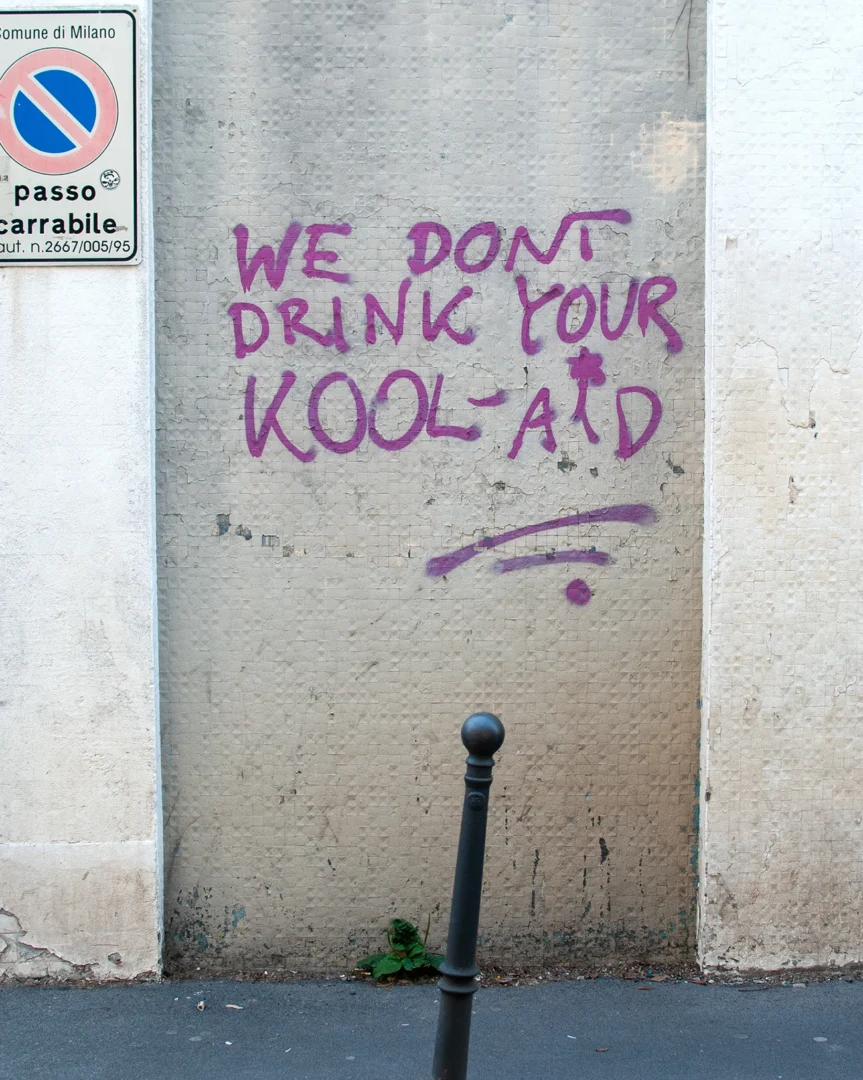

Unfortunately, this process spiraled into the kind of urban gentrification we know all too well. Developers and institutions co-opted the aesthetics and energy of the neighborhood, using slogans like Milan, capital of fashion and design to justify new waves of construction and speculation. he rhetoric of the “smart city” erased the district’s social fabric, pricing people out and turning authentic spaces into façades. When the squat was forcibly closed, we organized a week of workshops, debates, and public assemblies. We hung a banner on the building’s façade with the words Space and human resources—the two pillars of a civic project that had been shut down prematurely.

After leaving Isola, disillusioned and exhausted, I moved several times before settling in Lambrate with my wife Martina and our daughter, six years ago. I had given up on the idea of being active in Milan’s social fabric; I felt the city had betrayed me. Lambrate, though, is different. It’s a post-industrial, historically working-class neighborhood that retained the structure and spirit of a small village, despite having been annexed to Milan over a century ago. The area’s social legacy is still shaped by the Innocenti factory—an enlightened enterprise that, despite its contradictions, took responsibility for the well-being of its workers. ven here, when Via Ventura became part of Milan Design Week in 2010, local life was destabilized. Ground-level shops disappeared, property values rose, and daily life became harder.

I was still scarred by what happened in Isola and no longer wanted to invest myself in civic projects. he people in Lambrate knew my history and kept asking me to do something for the neighborhood. It was Martina who finally convinced me to act. One day she suggested we could try reviving the small, abandoned newsstand on Via Conte Rosso. And so, reluctantly at first, I decided to get back in the game.

Alioscia Bisceglia, Martina Pomponio e Michele Lupi – Aedicola Lambrate: redefining a traditional newsstand as a cultural and editorial platform

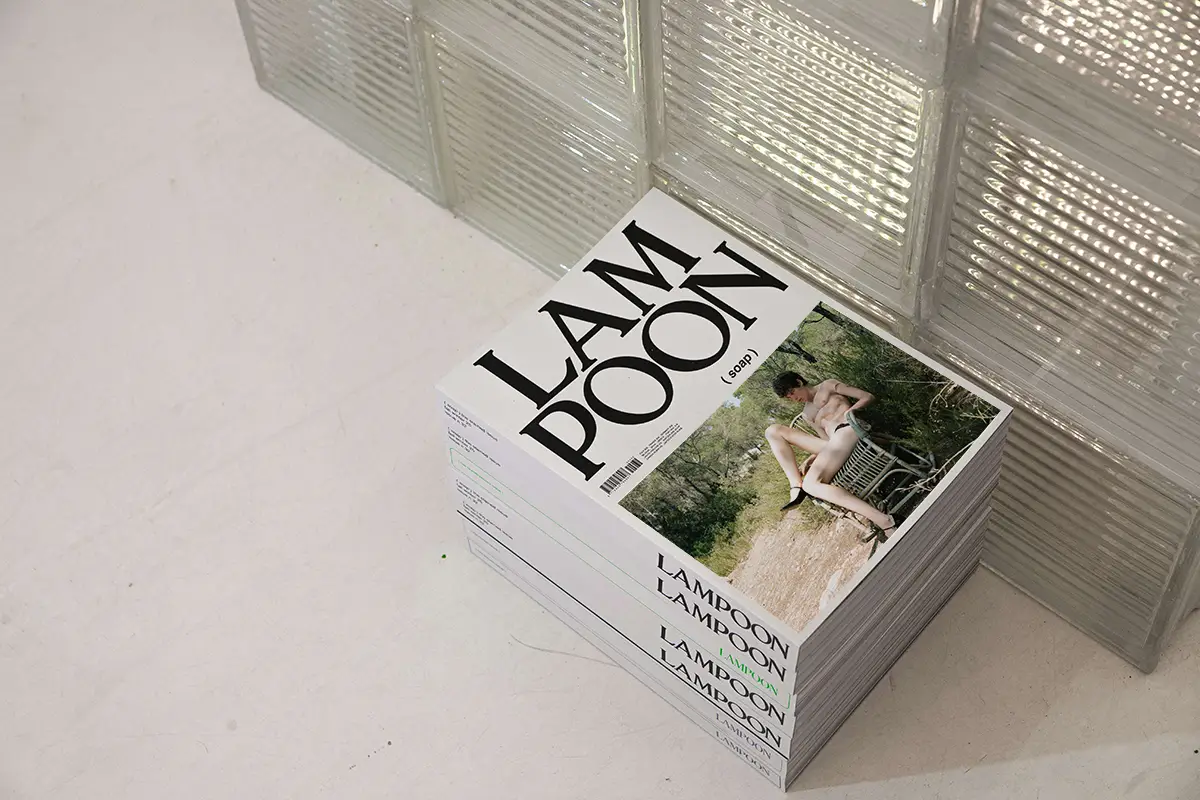

Together with Martina, we purchased the kiosk and founded Aedicola along with two other residents: Paolo Iabichino, a communication strategist, and Michele Lupi, who has lived in Lambrate longer than any of us. Aedicola is not the offshoot of a communications agency or a brand-awareness campaign disguised as local culture. It is a functioning, independent newsstand. From a business perspective, it’s not a profitable venture. t doesn’t need to be. The kiosk remains autonomous from any institutional framework; the only constraint we must adhere to is a municipal rule requiring us to display at least 60% editorial products. This explains why many newsstands around the city morph into cluttered, bazaar-style mini-marts selling snacks and toys to stay afloat.

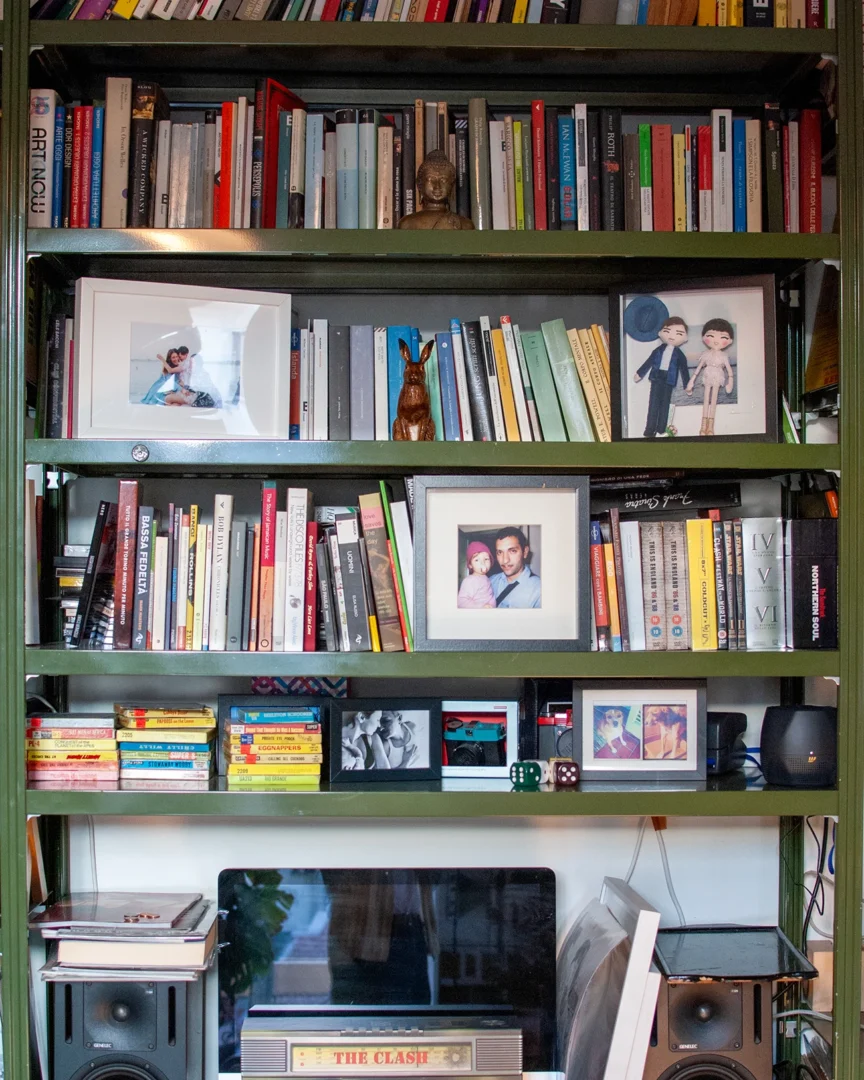

We wanted Aedicola to stay true to its nature. We sell newspapers, magazines, books, and we maintain a dedicated corner for small, independent publishing houses. The kiosk has become a space for collective readings, literary events, artist residencies, and curatorial projects. It’s an experiment rooted in the value of print, in the importance of slowing down, and in the richness of face-to-face conversation. The neighborhood has responded with enthusiasm and generosity—locals don’t just attend our events, they promote and protect them, becoming co-owners of the project in spirit. We receive no public funds. We are simply four private individuals who chose to invest in an idea of urban regeneration that values people over profit.

Reclaiming public architecture: the social role of a street-level kiosk in Lambrate

GDM: A newsstand is architecturally positioned in the middle of the street, disrupting the path of the distracted passerby. What is Aedicola’s role compared to traditional newsstands, and how has it integrated into the neighborhood?

AB: The historical newsstand of Lambrate dates back to the early 20th century, located on the same street as the current kiosk: Via Conte Rosso, which is still the main thoroughfare of the former municipality. Our current kiosk is not a vintage structure, but a more recent green-painted model—modern, functional, and, crucially, equipped with sanitation facilities. This may seem trivial, but it’s actually critical. Many newsstands close because the job is grueling, and the spaces are too small or inadequate. You must get up early, brave the cold, and work long hours in tight conditions.

The area surrounding Aedicola is rich in contrasts: just across the street are the ACLI offices (a Catholic association with leftist roots), and nearby there’s a squatted bakery raising awareness about citizenship and public health. The fabric of Lambrate is still woven through small-scale, village-like relationships. On Thursdays, for example, Aedicola becomes a hub for puzzle enthusiasts, who gather for the weekly release of crossword and puzzle magazines. I sometimes sit at the kiosk like a sociologist, observing the people who come by. I witness a cross-section of society. I notice who buys left-wing, centrist, or right-wing newspapers. Aedicola offers an alternative to digital alienation: it’s a moment of embodied community, the opposite of passive scrolling.

Like the space on Via Garigliano, Aedicola is rooted in a neighborhood vulnerable to real estate speculation. It is this very threat that makes the project one of civic resistance. I want to live in Lambrate as if it were a small ghetto—but one we embrace, a space of chosen community. Nicola Guiducci once described the Plastic Club as our ghetto with golden doors. Aedicola, in a sense, is our version of that idea.

From print to podcast: how Aedicola uses media production to build community engagement

GDM: Aedicola is a physical kiosk, with a newsvendor and readers, but it is also a virtual newsstand, producing podcasts, talks, and a special section for books, Aedicolanter Doc videos. It’s not virtual because it’s fake, but because it also communicates digitally.

AB: While we operate as a retail point for third-party content, we’ve also begun producing our own editorial content. At the moment, we distribute it primarily through social media. Our ambition is to become a small independent media outlet—what we like to call a “live magazine.” With the column Aedicolanter Doc, we engage audiences around the topic of reading and cultural participation. It’s a way to encourage deep attention in a world dominated by snackable content.

We see social media not as an end but as a tool to give something back to our community, particularly in a city like Milan, where competition and performance are the norm. Too often, community initiatives become performative spectacles, in which branding takes precedence over content. Milan has a whole ecosystem of ephemeral operators—visible, polished, and ultimately disengaged. here’s another Milan, one that’s quieter and more rooted in real life. When you start a family, you realize your priorities shift. You begin to seek stability and a sense of belonging.

Our newsvendor, Alessandro, is also a bookseller. This dual identity has allowed Aedicola to become a neighborhood bookstore—with a particular emphasis on social and political publishing. It’s a hybrid model: a traditional newsstand that meets the everyday needs of locals, and a curated space for reflection. We recently hosted an event where readers took turns reading the final page of their favorite books. It was a rainy day, but more than thirty people showed up. That kind of participation, without any brand backing or promotional budget, tells us something real is happening here.

Expanding beyond Lambrate: how a neighborhood newsstand becomes a citywide destination

GDM: Just like churches, each neighborhood has its own, and likewise, each one has its own newsstand. If I live in Lambrate, I don’t go to the newsstand in Maciachini and vice versa.Aedicola is a place visited daily by local residents, yet as a bookstore, it also draws visitors from across the city.

AB: Aedicola attracts people from outside Lambrate, largely because of our event programming. Sometimes visitors come expecting a sleek, design-forward kiosk, only to find a simple structure, full of life but not style-obsessed. We don’t want to become a glossy, Instagrammable object. The power of Aedicola lies precisely in its ordinariness and openness.

For example, on April 25th—Italy’s Liberation Day—we opened the kiosk by displaying only the Italian Constitution. Our guest was the writer and former magistrate Gherardo Colombo. The following year, we did something similar, this time presenting La Costituzione degli animali by Sara Loffredi, with guest Giuseppe Civati. These are quiet yet potent gestures. We’ve hosted events like Take Your Pleasure Seriously by Luca Barcellona, and organized a full week of discussions on youth distress during Civil Week. Our book selection is curated to include works on alternative economies, reflecting our interest in the third sector and cooperative models.

Looking ahead, we hope to expand. Aedicola could become a blueprint for other local initiatives. One project already underway is a rewilding effort supported by a grant from a cosmetic brand. With their help, we planted indigo in the green area next to the kiosk. That space could eventually become the seed for a local energy community, or perhaps a platform for children’s publishing, connecting local schools with our programming. Creating a community on a human scale—that’s the real goal. Not a smart city, but a sensitive one.

Urban resistance through print: why newsstands still matter in digital society

GDM: Aedicola serves both as a retail space and as a point of information, thanks to a series of projects that go beyond mere sales.

AB: Aedicola is a place for the circulation of thoughts as much as goods. Lambrate is changing, fast, under the pressures of real estate speculation. Rather than passively watching this transformation unfold, we believe it’s better to face it together, as a collective. In many ways, Milan is starved for social spaces. For people like us—those not entirely consumed by careerism—there’s an urgent need for physical spaces of exchange.

Newsstands, especially in post-industrial neighborhoods, can become active sites of resistance. Ours is a grassroots, informal project. No research committees, no institutional theory behind it. It may sound idealistic, but self-managed spaces still matter. People need somewhere to express themselves, to gather, to build. In a city that isolates, Aedicola helps people not feel alone.

Most of our lives are now lived indoors, mediated through screens. We believe we belong to a community because we have followers—but we rarely cross paths with people different from us. At Aedicola, we do. People with opposing ideas come into contact. And sometimes, in those small, unspectacular encounters, something changes. We begin to understand each other. That’s when distance becomes dialogue. And that’s where cities can start to heal.