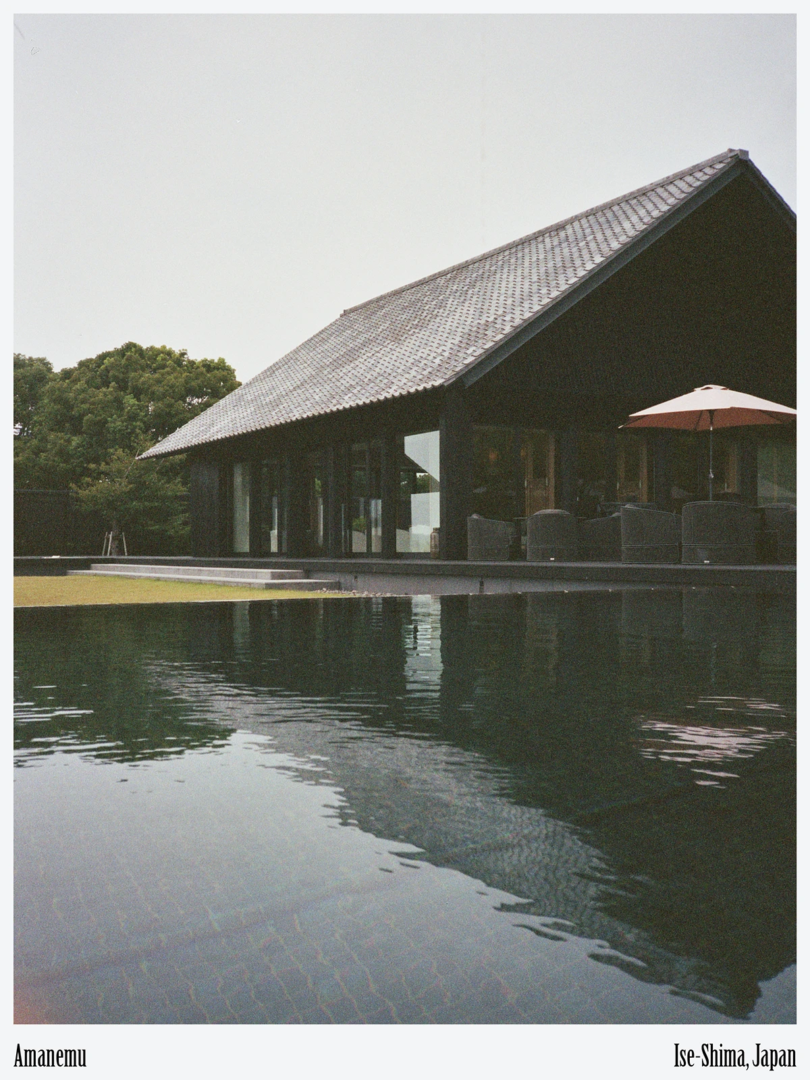

Amanemu: natural hot springs and black cedar in Mie Prefecture

Amanemu by Kerry Hill Architects in Japan’s Ise-Shima National Park is built from local stone and cedar, featuring geothermal hot springs and a sustainable design rooted in tradition

Amanemu: equilibrium between stone, forest, and sea – opened in 2016 and designed by Kerry Hill Architects

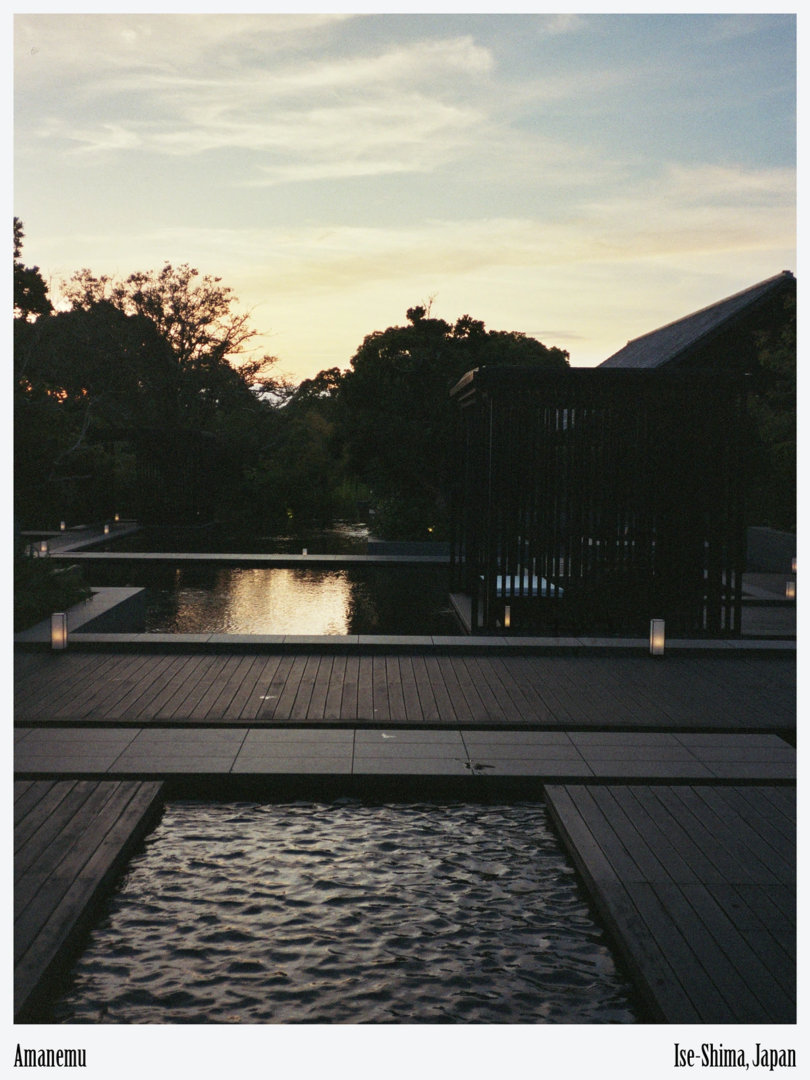

Between the wooded ridges of Shima Peninsula and the still surface of Ago Bay, Amanemu rises from the ground as if drawn from the same mineral layer. The bay, known for its floating rafts used in oyster and pearl cultivation, defines the rhythm of this coastal region — a geography shaped by salt, mist, and silence.

The resort extends over two hundred and fifty thousand square meters within the Ise-Shima National Park, in Mie Prefecture, an area historically linked to the Imperial Shrine of Ise, one of Japan’s most sacred Shinto sites. Here, the balance between human presence and landscape is a cultural rather than aesthetic matter: a way of inhabiting rather than transforming.

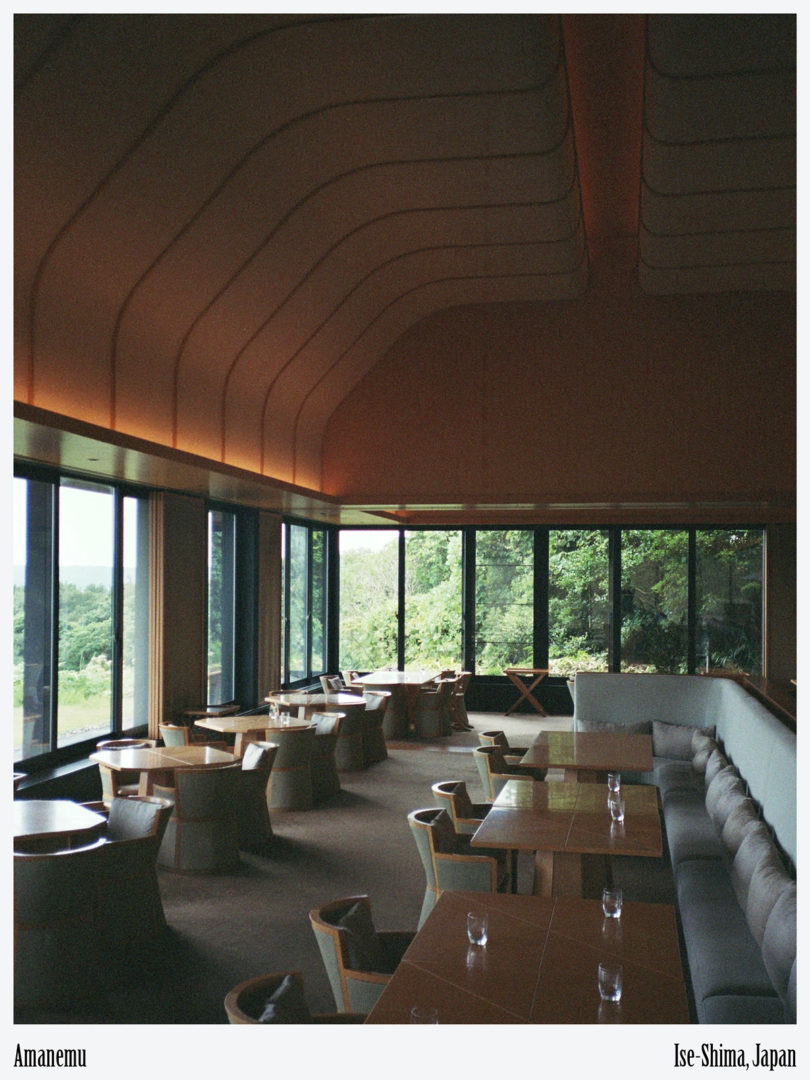

Opened in 2016 and designed by Kerry Hill Architects, Amanemu continues the practice of the studio’s founder, known for translating regional craft and climate logic into contemporary minimalism. The project recalls the traditional minka houses of rural Japan — low, elongated, rooted in the earth — and the architecture of ryokan, the thermal inns where life unfolds around water.

Rough architecture: Gaya stone and the blackened cedar that absorbs the heat

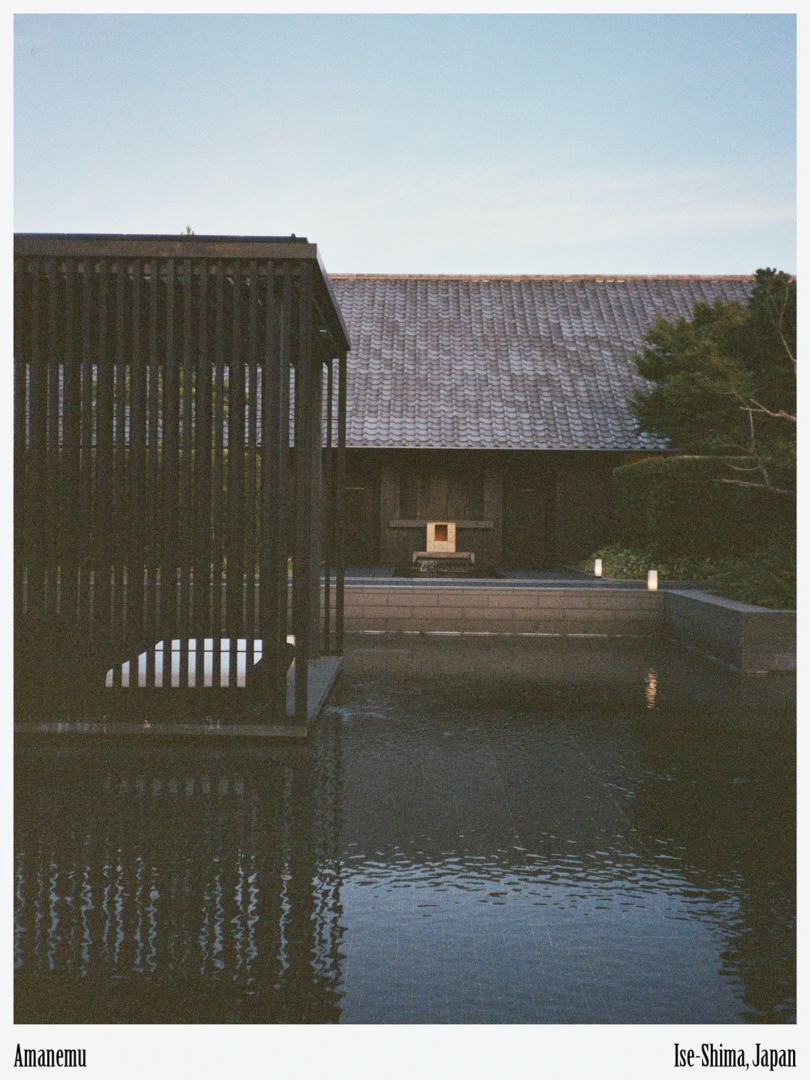

The architecture of Amanemu is a study in local geology. The main structures are built with Gaya stone, quarried nearby in Mie Prefecture. Volcanic in origin, the stone carries subtle tonal variations — greys, dark browns, and traces of iron. Used for the foundations, paths, and terraces, it grounds the complex both physically and symbolically in the surrounding soil.

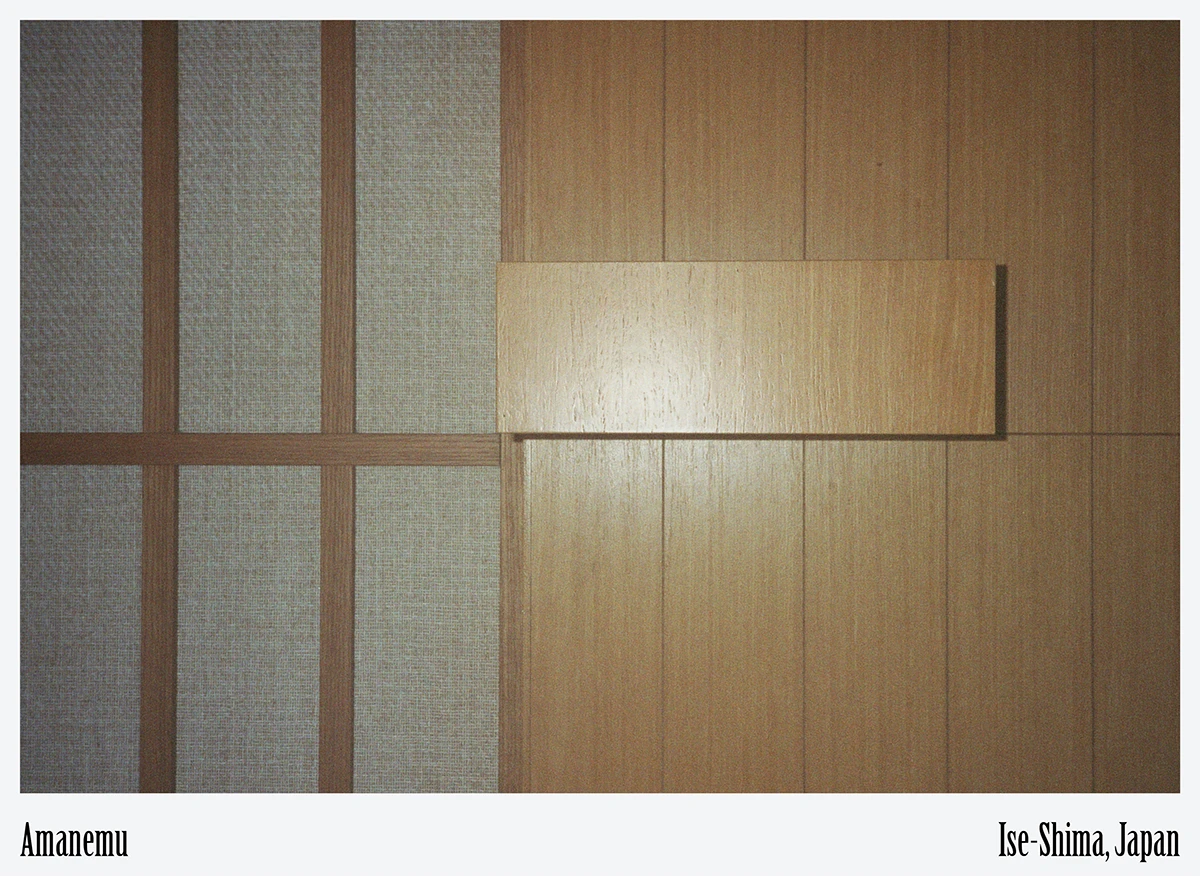

The exteriors are clad in Japanese cedar treated with yakisugi, an ancient technique in which the surface is lightly charred. The carbonized layer darkens the wood, making it resistant to rain, humidity, and insects, and creating a form of natural insulation. The result is a deep matte black that absorbs humidity and stabilizes interior temperatures. It is a reversal of Mediterranean logic, where whitewashed walls are meant to reflect heat — in Japan’s humid climate, darkness protects the material and preserves the cool.

This contrast between cultures of heat becomes a metaphor for Amanemu’s approach to architecture: local observation rather than imported formula. The cedar cladding is not purely aesthetic but functional, derived from centuries of adaptation to monsoon and salt air.

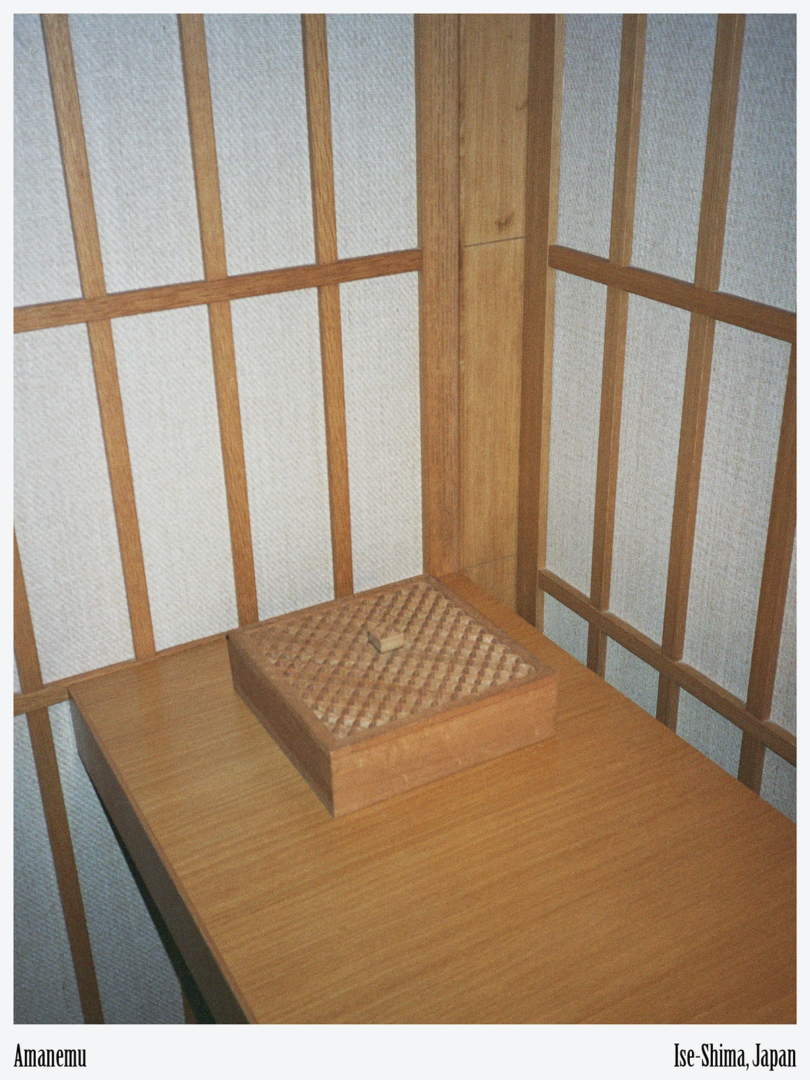

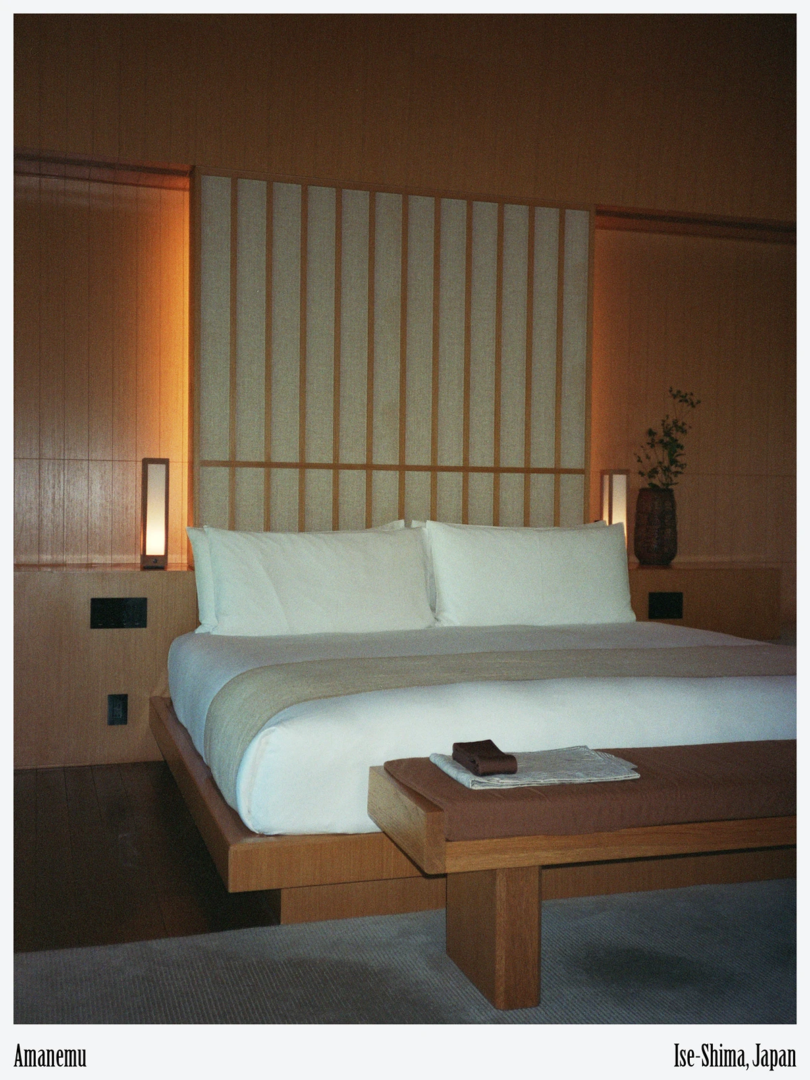

The interiors are finished in pale Japanese timber, mostly white oak, a species valued for its strength and the way it refracts light. Floors, panels, and furniture remain untreated, allowing the grain to absorb the filtered sunlight that enters through sliding doors of woven textile. Chandeliers and lighting fixtures were custom-designed by Kerry Hill Architects, combining paper, bamboo, and metal in geometric frames that reinterpret traditional Japanese lanterns.

Amanemu, sustainability as continuity: forest, fauna, and the balance of maintenance

Located within a national park, Amanemu is surrounded by a natural ecosystem that predates its construction. About twelve thousand trees have been planted since the opening, complementing an existing forest of maples, pines, and camellias. The latter, Camellia japonica, grows spontaneously across the property, its red blossoms scattered over the moss in winter.

Wildlife moves freely around the resort: foxes, raccoon dogs, rabbits, deer, and monkeys. Eagles and kites circle above Ago Bay. Near the spa, a small family of wild boars — the inoshishi — has taken residence; their image appears on the in-room linen cards used to indicate reduced laundry service. Guests who choose to limit washing cycles contribute to the Shima City SDGs Promotion Fund, which supports local sustainability projects.

Energy use follows seasonal logic: pool heating is suspended during summer, and air conditioning minimized through cross-ventilation. The principle is one of sustainability by design — an architecture that breathes rather than consumes. The black exteriors absorb warmth in winter, reducing the need for artificial heating, while the forest canopy creates natural shade in summer.

The resort’s design does not seek isolation but integration. Paths are unpaved in part, allowing rainwater to percolate naturally; lighting at night remains subdued to protect nocturnal species. Each maintenance action is part of a wider ecological rhythm.

Raw Materials and thermal rituals: how water defines the architecture

Amanemu’s identity is inseparable from its natural hot spring, the only one in the Aman portfolio in Japan. The spring water surfaces at thirty-seven point two degrees Celsius and is gently heated to forty-two degrees Celsius for bathing. The process is cyclical — no cooling is needed, only controlled reheating. A continuous flow circulates through the pools and private onsen baths, filtered for hygiene while maintaining mineral integrity.

The bathing experience follows Japanese tradition. Rooms are equipped with deep tubs of basalt stone, their dark surfaces reflecting the garden outside. The contrast of black basalt and pale wood recalls the dualism that runs throughout Amanemu — hot and cold, light and shadow, water and earth.

The spa’s herbal treatments rely on ingredients collected from the surrounding forest: yomogi (mugwort) in spring, biwa and lemongrass in summer, sansho (Japanese pepper) and cinnamon in autumn, azuki beans in winter. The herbs are hand-dried and infused into oils and balms. These preparations connect Amanemu to a lineage of regional medicine where the forest provides both resource and ritual.

Camellia oil, extracted from the seeds of Camellia japonica, is used in traditional Japanese skin care and in the resort’s spa treatments. The cycle of collection and renewal mirrors the natural pace of the forest: nothing industrial, nothing decorative.

Sustainable hotellerie: rice, milk, and the marine geography of Ise-Shima

The Ise-Shima region has built its economy and culture around the sea. The calm surface of Ago Bay hides oyster farms and the famous Mikimoto pearls, cultivated since the late Nineteenth century. The tradition continues today in the same waters visible from Amanemu’s terraces. Local fishermen provide fresh seafood, including the prized Ise lobster, while smaller producers supply vegetables and seasonal greens.

Every morning, milk from the nearby Yamamura dairy is delivered to the restaurant. The rice served at Amanemu is grown exclusively for the resort in Suzuka City, also within Mie Prefecture. Staff members join the planting and harvesting process — an exercise in proximity and awareness.

Contrary to common belief, rice in Japan is not grown continuously year-round; it follows a single annual cycle tied to the monsoon. However, Amanemu’s partnership with small-scale farms allows for rotation across fields, ensuring consistent quality and soil preservation.

The restaurant’s sake list is curated by the in-house sommelier, focusing on the region’s breweries that combine centuries-old methods with small-scale production. Sake here is not a symbol of luxury but an expression of geography — each bottle linked to the same climate and water that feed the rice paddies and the hot springs.

This network of collaborations defines Amanemu’s model of sustainable hotellerie: a hospitality system rooted in the ethics of proximity rather than in spectacle.

Human commitment: craft, labor, and the continuity of cultural memory

Amanemu’s stillness conceals a dense web of human work. Carpenters, stonemasons, gardeners, and textile artisans from Mie Prefecture contributed to its construction and continue its upkeep. The principle of human commitment shapes both the architecture and the daily operations: maintenance as preservation of knowledge.

Interior furniture was produced locally in oak and ash; fabrics for curtains and seating include natural compositions of linen and viscose, some woven specifically for the project. The choice of materials prioritizes touch and longevity over novelty — each surface meant to age visibly.

The resort also integrates the work of Genbei Yamaguchi, an obi and kimono artisan from Kyoto whose family has led silk weaving for over two hundred and seventy years. His pieces, mounted as wall panels, connect the interiors to a lineage of Japanese textile artistry, turning each villa into a quiet archive.

The act of hospitality extends beyond service: gardeners maintaining the moss, cooks testing local rice varieties, technicians monitoring the mineral content of the spring. The structure’s permanence depends on a network of small, repeated human gestures — evidence that architecture, here, remains a living process.

Time, weather, and the meaning of endurance

Over the years, Amanemu’s cedar walls have deepened in tone. Rain leaves marks, moss rises along the stone paths, metal fixtures tarnish. The process is not corrected but accepted — a philosophy aligned with the Japanese notion of wabi-sabi, where beauty resides in transience and imperfection.

The resort’s identity is therefore less about design than about duration. The landscape reclaims what architecture offers; the black surfaces absorb the scent of salt and cedar. The result is not a monument but a condition — a place where the passage of time is visible, where rough materials become smooth through use, and where silence holds the same weight as form.

Amanemu

Amanemu is a hotel located within the Ise-Shima National Park in Mie Prefecture, Japan. Opened in 2016 and designed by Kerry Hill Architects, it comprises twenty-four suites and eight villas built with locally sourced Gaya stone and cedar. The property includes natural hot spring facilities and a restaurant that works with nearby producers for its ingredients. The project reflects a contemporary interpretation of traditional Japanese architecture and its relationship with the surrounding landscape.