Living Archives of Art Deco: How Two Brussels Villas Became Belgium’s Blueprint for Modernism with a Memory

From static masterpiece to adaptive monument, Villa Van Buuren and Villa Empain show how Belgian Art Deco mastered both permanence and reinvention

Villa Van Buuren, Villa Empain: two houses, two fates

France gave Art Deco its name. New York gave it a skyline. Belgium, true to form, gave it structure and a borderline obsessive attention to finish. While the rest of the world chased spectacle, Belgian architects built with restraint streamlined facades, exacting materials, and interiors that looked curated even before they were finished.

The clearest expressions of this quiet intensity still stand in Brussels: Villa Van Buuren and Villa Empain. Two houses. Same city. Same movement. Same era. But radically different fates. One froze itself in time as a domestic gesamtkunstwerk. The other was left behind, occupied, stripped down, and eventually resurrected as a public cultural institution.

What they share is not just a design language, but a national instinct to do modernism without noise, and to treat architecture as both artifact and argument. Belgium didn’t just adopt Art Deco. It outlived it,quietly, and with impeccable taste.

Designing Taste: Belgian Art Deco in Context

Art Deco in Belgium was less a rupture than an evolution. It emerged not in opposition to the curvilinear Art Nouveau that preceded it, but as a cooler, more geometric continuation. Belgian designers drew from French luxury, Dutch rationalism, and Viennese clarity, balancing decorative ambition with spatial restraint.

The result was a hybrid style that thrived in private commissions and boutique scale buildings rather than grand public works. Materials mattered rare woods, marbles, custom glass and so did craftsmanship. But just as crucial was the integration of architecture, interior design, and art into a coherent whole.This synthesis finds its fullest expression in Villa Van Buuren.

Villa Van Buuren: A Total Work of Art Preserved in Time

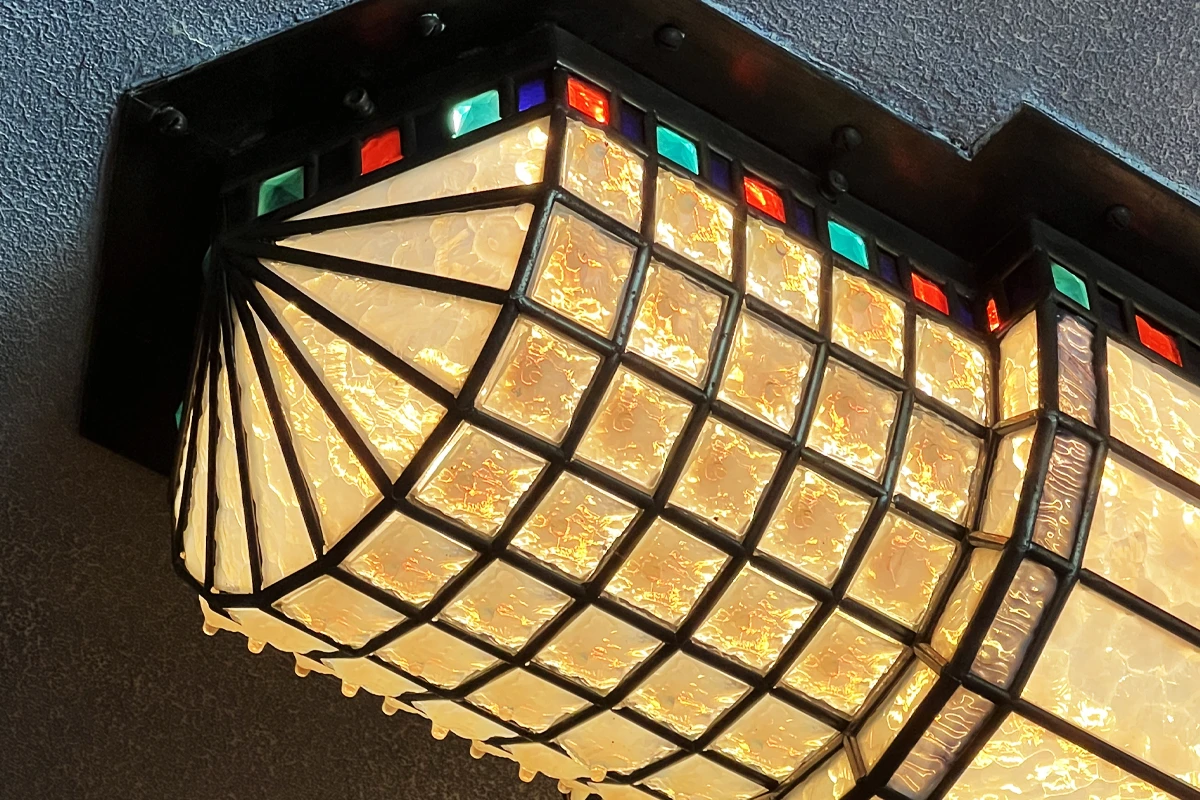

Nestled in the residential Uccle district, Villa Van Buuren was commissioned by banker David Van Buuren and his wife Alice art collectors, cultural patrons, and meticulous tastemakers. Designed by architects Léon Govaerts and Alexis Van Vaerenbergh, the house exemplifies gesamtkunstwerk: a “total work of art” in which every element, from the stained glass to the carpets, was created or selected to form a unified aesthetic environment.

The exterior draws from Dutch modernism, its brick façade modest and unassuming. Step inside, however, and the narrative shifts. The interiors are an intricate ballet of inlaid woods, sculpted light fixtures, and original furniture by Belgian and international designers. The couple’s extensive art collection including works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, James Ensor, and Gustave Van de Woestijne is embedded seamlessly into the domestic landscape. Nothing here is staged; everything is intentional.

Remarkably, the house has remained untouched since the 1930s. After Alice Van Buuren’s death in 1973, the home was converted into a museum under a foundation bearing the family’s name. As a result, Villa Van Buuren functions today not just as a house museum, but as a pristine document of interwar elite taste.

Landscape as Narrative: The Gardens of Van Buuren

Equally important is the villa’s garden, which evolved alongside the house. The original layout by Jules Buyssens featured sharp geometries and structured paths hallmarks of early 20th-century Belgian landscape design. Later additions by René Pechère, including the “Garden of the Heart” and the “Labyrinth of Life,” introduced a layer of symbolic storytelling that complemented the home’s interior aesthetic.

More than decorative green space, the gardens function as an emotional and philosophical extension of the villa. Together, house and landscape present a rare example of fully integrated design where architecture, interior, and nature are in deliberate dialogue.

Villa Empain: Monumentality, Decline and Reinvention

On the other side of Brussels, Villa Empain offers a starkly different trajectory. Commissioned by Baron Louis Empain, heir to an industrial fortune, and designed by Swiss architect Michel Polak, the villa was completed in 1934. Its aim was clear: to project cultural capital and architectural prestige.

Unlike the intimate scale of Van Buuren, Empain is monumental symmetrical, clad in polished travertine, and punctuated by bronze details. The layout is formal, almost palatial, with axial symmetry and vast reception spaces. Materials are opulent, but the style remains reserved, closer to Streamline Moderne than ornamental flourish.

A Revival by Design: The Boghossian Restoration

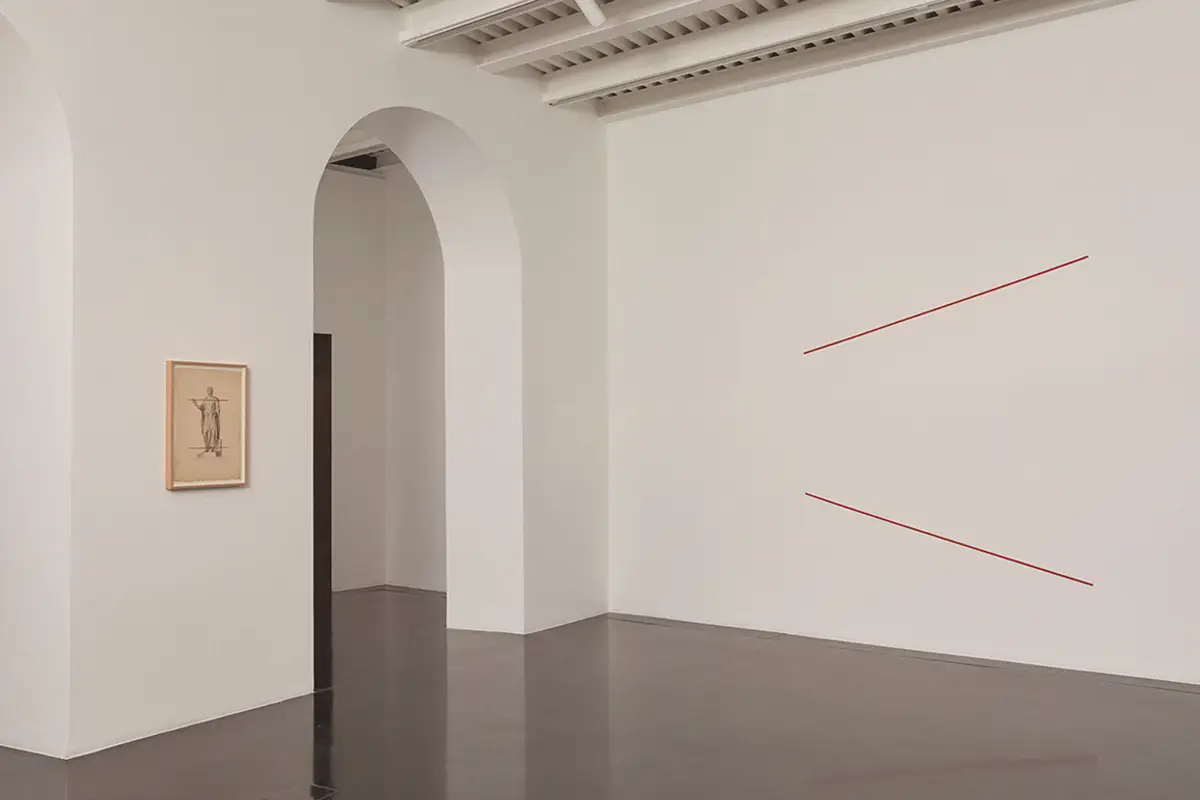

In 2007, the Boghossian Foundation acquired Villa Empain and began an extensive restoration process, completed in 2010. The project was ambitious,not just in reviving the physical structure, but in reimagining its use.

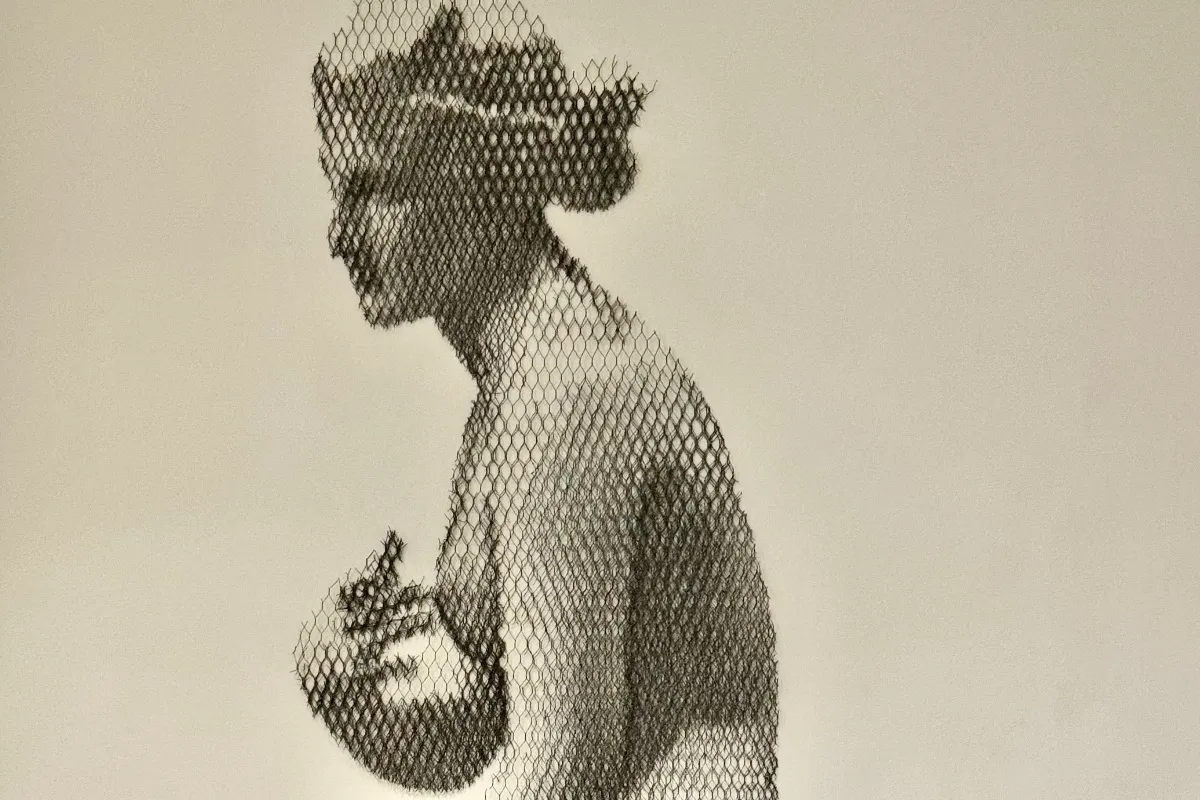

Today, the villa operates as a cultural hub focused on East-West dialogue. Its rooms, once designed for private display, now host exhibitions, installations, and public events. The restoration preserved original materials wherever possible, while adapting the space for contemporary use striking a balance between historical fidelity and functional reinvention.

Two Villas, Two Visions of Legacy

Villa Van Buuren and Villa Empain reflect two distinct trajectories of architectural heritage. One prioritizes preservation maintaining the house exactly as it was conceived, down to the positioning of artworks and the grain of the wood paneling. The other embraces adaptive reuse transforming a private space into a platform for public cultural production.

Both strategies offer valuable lessons in how design history can be activated today. Van Buuren offers intimacy and continuity; Empain offers scale and redefinition. Both serve as touchstones for Belgian Art Deco proof that even within a restrained national style, there is room for radical variation.

Why It Matters Now

As questions of conservation, sustainability, and cultural relevance reshape architectural discourse, these two villas offer models worth studying. They demonstrate that heritage is not a static condition, but a set of choices how we value the past, how we reuse space, and how we frame beauty as a form of cultural memory.

Benedicta Addoteye