Belvedere and the making of cosmopolitan Mykonos

A 19th-century villa transformed into a “petite-grand hotel” where Cycladic architecture, international gastronomy, and curated sociability converge: a story within the larger story of Mykonos

High in the heart of the Chora, between the chalk-white Cycladic architecture and the razor-blue Aegean, the Belvedere Hotel Mykonos began as a 19th-century “big house” that, over more than half a century, has become a cultural device: a place that bridged the bohemian spirit of the 1960s–70s and the international glamour that would turn the island into a Mediterranean icon. To understand its role, one must begin with the moment when Mykonos itself rose from marginality to global attention: the years of the international jet set.

How Mykonos became a jet-set paradise: celebrities, counterculture, and cultural freedom in the 1960s–70s

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, Mykonos was still a windswept island on the margins of Greece, its economy tied to fishing and migration. Yet in less than a decade it became a beacon for the global elite. The arrival of Aristotle Onassis’ yacht Christina O in nearby waters, carrying guests like Winston Churchill and Maria Callas, helped place Mykonos and its sister island Delos into the spotlight. Soon after, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis made appearances on the island, immortalized by photographers who turned her strolls through narrow alleys into international images of style.

Fashion magazines followed quickly. Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Elle sent photographers to capture the dazzling light of the Cyclades, staging shoots against whitewashed walls, windmills, and turquoise sea. Grace Kelly and Richard Burton appeared in photographs and society pages, merging Hollywood glamour with the rustic simplicity of island life. The imagery traveled worldwide, presenting Mykonos as both authentic and glamorous.

At the same time, Mykonos attracted a very different audience: artists, writers, and free thinkers searching for spaces of liberation. The 1970s saw the island become one of the first in the Mediterranean where the LGBTQ+ community could live and celebrate openly, thanks to a local atmosphere of tolerance and the international bohemian presence. Bars and clubs became laboratories of new forms of nightlife—spaces where counterculture met jet set. Mykonos thus embodied a paradox: it was simultaneously the playground of global elites and a haven of freedom for communities and cultures facing obstacles elsewhere.

Archaeology also played its role. Delos, a sacred island of antiquity, is one of the most excavated sites in the world. Proximity to its ruins made Mykonos a natural gateway for visitors drawn by history as well as leisure. Tourism policies promoted by the Greek government, combined with the boom of air travel, meant distances shrank. Within a few years, Mykonos went from isolated outpost to stage of international cultural encounters.

Piero Aversa and the invention of Belvedere’s cultural DNA in the 1970s

In the middle of this transformation stood Mansion Stoupa, a neoclassical residence on the slope above the Chora. Around 1970, Italian-American painter Piero Aversa rented the villa and transformed it into a salon of Dionysian evenings. Aversa was no ordinary visitor: he moved between New York’s fashion and design circles, Palm Beach society, and the artistic scenes of Key West. His temperament was expansive, his social reach international.

At Mansion Stoupa, Aversa hosted dinners as performances, nights where collectors, designers, and journalists mingled with island locals. His approach to hospitality—where the house itself became a stage and conviviality an art form—reshaped the villa’s identity. Beyond his canvases, which ranged from still lifes to decorative patterns, Aversa left a legacy of atmosphere: the idea that hospitality begins with the writing of a mood.

He was also involved in the creation of Pierro’s, the bar that opened in 1972 and quickly became an institution of Mykonos nightlife. Through Aversa, the Belvedere’s DNA began to take shape: eclectic, international, yet rooted in Mykonos’ spirit of freedom and performance.

Mansion Stoupa and the Campanis/Ioannidis family: from a 19th-century residence to the seed of hospitality

The origins of Belvedere trace back to the 19th century, when Mansion Stoupa was built as an architectural exception among Cycladic cubes. Its ornamental pillars and, above all, its rare garden—lush with bougainvillea and Mediterranean plants—distinguished it from the stark, wind-beaten landscape. For the Cyclades, where the Meltemi winds limit tall vegetation, a cultivated garden was both anomaly and symbol of distinction.

Passed down through the Campanis/Campani family to Sofia Ioannidou-Campanis, the villa began to be rented in 1969, at first as a summer house for visitors. Even in the 1920s, however, international guests had been received there, confirming its vocation as a prototype of cosmopolitan sociability. The Ioannidis family would later take this vocation further, transforming the villa into a permanent platform for encounters that merged local traditions with international currents.

From private villa to “petite-grand hotel”: the Belvedere’s transformation in the 1990s

The decisive turning point came in the mid-1990s, when Mansion Stoupa was officially converted into Belvedere Hotel. The Ioannidis family embraced the idea of a “petite-grand hotel”: not a colossal resort with hundreds of rooms, nor a micro-boutique isolated from context, but a medium-sized organism where privacy and sociality coexist.

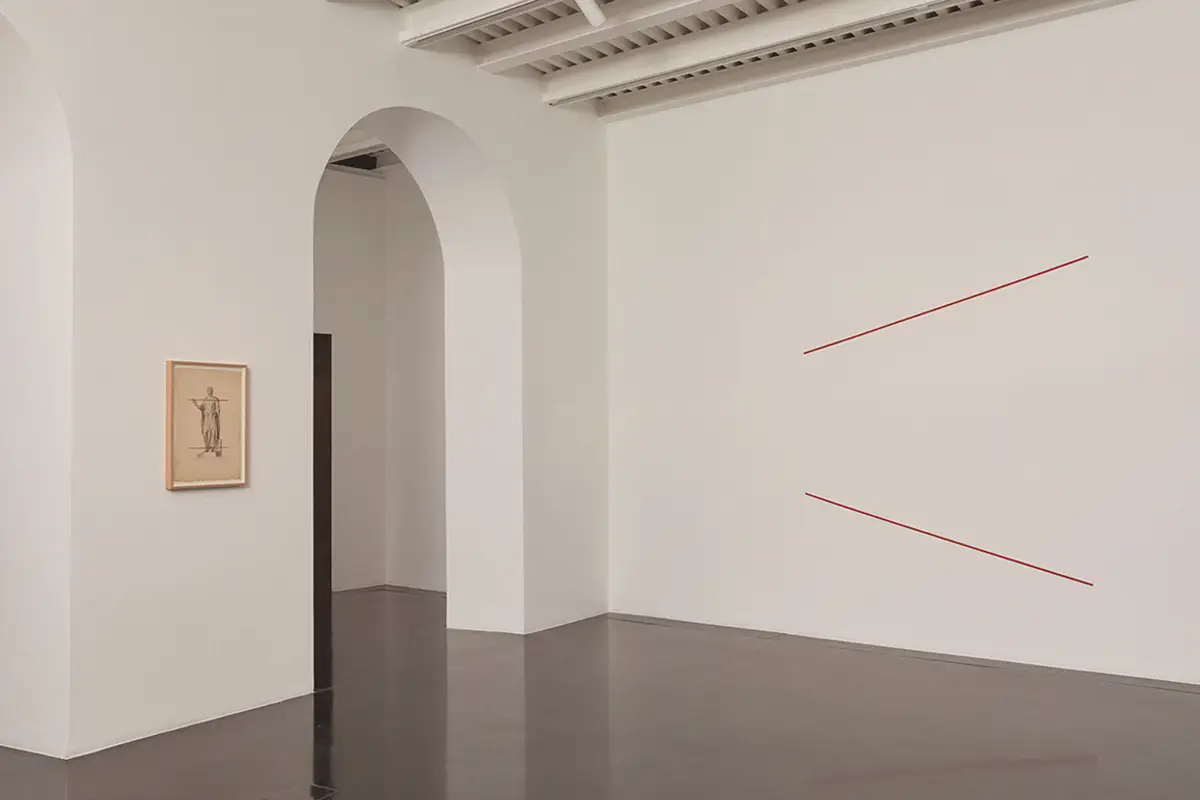

The layout followed Cycladic urbanism. Whitewashed structures were arranged around a central pool, creating a chamber that protected from urban noise while concentrating social life in shared spaces. The main body—today Main Hotel Rooms & Suites—was complemented by Hilltop Rooms & Suites, Waterfront Villa & Suites, and Villa Next Door & Suites. Each preserved the local architectural alphabet: limewashed curves, natural wood, dry-stone walls, and ramps adapted to the slope. International media soon described the Belvedere as “a small Greek village on a hill,” with panoramic views over the Chora.

Cycladic architecture and ecological hospitality: designing with wind, light, and scarcity

To belong to the Cyclades means to build with scarcity. The Meltemi winds, which in summer can reach 7–8 Beaufort, dictate construction logic: compact masses to resist gusts, narrow lanes to break the wind, small balconies, and thick white walls to reflect glare. The Belvedere mirrors these rules. Its courtyards, pergolas, and terraces are not decorative but bioclimatic: they temper the climate while shaping atmosphere.

The garden, inherited from the 19th century, is a cultural gesture. In a place where arboreal growth is rare, the Belvedere has cultivated bougainvillea and drought-resistant Mediterranean species. Bougainvillea in particular is more than aesthetic: it is a plant suited to full sun, drought, and salt, offering shade and chromatic framing without imposing mass. Its presence across the hotel—and across Mykonos—embodies resilience and identity.

The result is a balance between architecture and ecology: the Belvedere sits in the landscape without disguising it, adapting to scarcity and wind rather than fighting them.

Belvedere as a cultural and social hub: music, art, and curated atmosphere

From the late 1990s onward, the Belvedere reasserted its role as social hub. White Parties and the Pool Club became contemporary piazzas where atmosphere mattered more than spectacle. Music was central: Arman Naféei, a cultural curator with experience across fashion and hotels, helped define a sonic identity that distinguished the Belvedere from the hyper-amplified beach clubs. The legacy of Hans Havenaar, known as “The Dutch Touch,” resident DJ for over a decade, is preserved in the memory of the community.

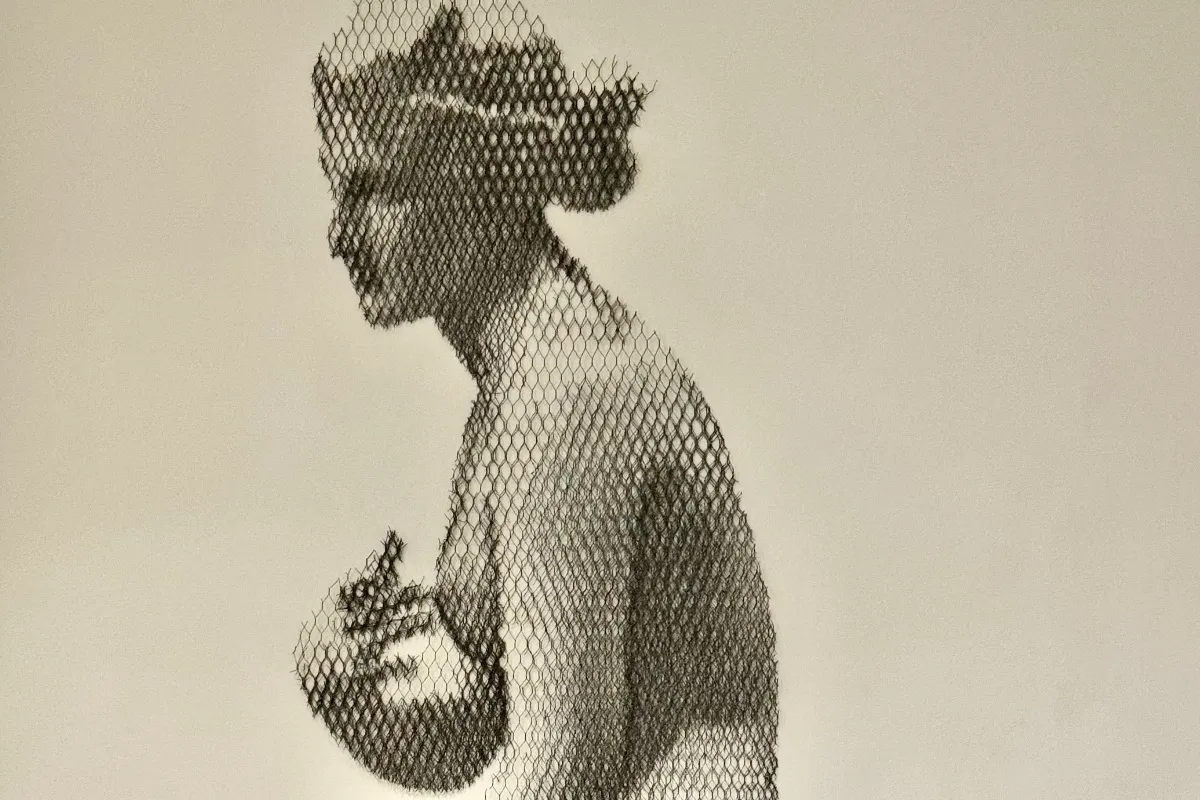

Visual culture has also been part of this positioning. In recent years, collaborations with artists and designers have reinforced the Belvedere’s hybrid identity between hospitality, art, and lifestyle. Among them, British artist-designer Luke Edward Hall brought his saturated colors and whimsical take on classicism, aligning the hotel with a broader network of fashion and interiors. His involvement marked the continuation of Belvedere’s tradition of connecting hospitality with cultural creation.

From Nobu Matsuhisa to cocktail culture: Belvedere as a dining landmark

In 2003, a chance meeting in London led to the opening of Matsuhisa Mykonos, the first open-air Nobu restaurant worldwide. This was not only a milestone for the island but also a new model for Greece: haute cuisine presented as cultural programming equal to lodging. In 2023, the twentieth anniversary was celebrated with an omakase week that brought international guests to the Chora.

Next door, the Sunken Watermelon Cocktail Bar extended the hotel’s philosophy to mixology. Its design echoes the garden with blues, yellows, and greens, and its rhythm follows the entire arc of the day: from shaded mornings to after-dinner gatherings. Unlike venues that stage “the Mykonos night,” the Sunken Watermelon composes a full-day cadence aligned with the Belvedere’s aesthetics of measure.

Hilltop Rooms & Suites: extended stays, privacy, and the second pool

Two hundred fifty meters above the main property, Hilltop Rooms & Suites added a new chapter to the Belvedere. With 26 suites ranging from 30 to 50 square meters, designed by Domna Ioannidis, the Hilltop emphasizes curves, natural tones, and views of the windmills and the Aegean.

In 2024, a rectangular pool was inaugurated for the exclusive use of Hilltop guests. Its placement was more urbanistic than decorative: it created a second piazza, offering privacy while expanding possibilities for social life. Hilltop also introduced the idea of extended stays—longer residencies that privilege belonging over brief visits—positioning Belvedere as more than a stopover, but as a home.

Samuel Hernest