180 hectares of biodynamic agriculture: La Raia, a case study

Agriculture as an entrepreneurial art: biodynamics, short supply chains, the Barolo wine market, renewable energy: a visit to La Raia and a conversation with Piero Rossi Cairo

Langa, the hazelnuts, and the hectares cultivated for Barolo

Langa territory, which was a wooded area made up of hills seventy years ago, was known for its hazelnuts. “Ever since the Nebbiolo fever for Barolo exploded, if you find a tree you have to give thanks and light a candle. They have uprooted everything.” Today, the market foresees a value of up to three million euros (with possible higher peaks depending on the cru) for the purchase of one hectare of land for Barolo wine production. “You need to add equipment and operational costs every year. If all works out well, you can produce up to ten thousand bottles per hectare. Even at 40 euros per bottle—which is already an off-market price—how many years will it take to break even? On the other hand, if these lands come to you through inheritance, you are sitting on gold.”

The Estate – La Raia and the Rossi Cairo family: Demeter certification

La Raia Estate was purchased by Giorgio Rossi Cairo in 2002 – this conversation is with his son Piero. Biodynamic farms are certified. “We became organic in 2005 and in 2007 we became biodynamic with Demeter certification.” The name Demeter refers to Demeter, the ancient Earth goddess. The Demeter symbol was introduced in 1928 after the first courses held by Rudolf Steiner in Poland. It was illegal to recognize Demeter during the Nazi years. It was reinstated with force in 1946. From then on, the standards and codes that define a Demeter certificate have evolved following scientific research into biodynamic agriculture. The foundation is the agrarian mosaic: woods, meadows for grazing, hedges and bushes, horticultural and field areas. These are called ecotones, and their coexistence acts as a mutual catalyst.

Gavi from Genovesato: 50 hectares of vineyard

Gavi is produced in 11 municipalities in the area once known as Oltregiogo, that is—coming from Genoa—those territories beyond the Maritime Alps and before the plain. Lands that once belonged to Genovesato, the area dominated by Genoa. The Italian word Liguria would come much later with the Unification of Italy under the Savoia king.

“Even if I wanted to plant 50 hectares of Gavi, I couldn’t have done it. The planting authorizations for Gavi’s cortese grape are limited and assigned based on a score, 30 hectares each year. I am in favor of these restrictions: one of the crises facing wine, which is a cyclical crisis, is an excess of supply.” At La Raia, they cultivate 50 hectares of vineyard – some vines are seventy years old. Another 60 hectares are dedicated to pasture for the Fassona breed and cereal cultivation. The remaining 70 hectares are wooded or otherwise returned to the natural cycle.

Forest, regenerative agriculture vs. traditional, organic and biodynamic

The forest litter among the deciduous leaves and broken, fallen wood that decay in the humidity, provides an environment for soil microorganisms. Invertebrates, fungi. Through these microorganisms, carbon is sedimented and transformed into food for plants. The soil of a forest is a macro-organism. From the forest, quails and hares venture among the vineyards – both threatened by hunters and herbicides still used in intensive and traditional agriculture. “Regenerative agriculture supporters point out that removing forested areas impoverishes the soil, that means decreased fertility of hectares. Vines require the use of substances introduced by man, both in organic and biodynamic farming.”

On the walls of the village of Gavi, sheets with instructions are hung. It’s June – we are in the phase of separate flower buds. There has been a lot of rain in recent weeks. Copper and wettable sulfur are expected against downy mildew and anthracnose. Cow horn manure is prepared 500 – and is applied as an inoculant. Preparation 501, made of silica, is similar. Before being applied, they are dynamized in water at 37 degrees – i.e., dissolved in moving water that oxygenates the microbiology.

Ladybugs among the spelt, green manure, deer, wolf, red partridge, fox, and freshwater crayfish

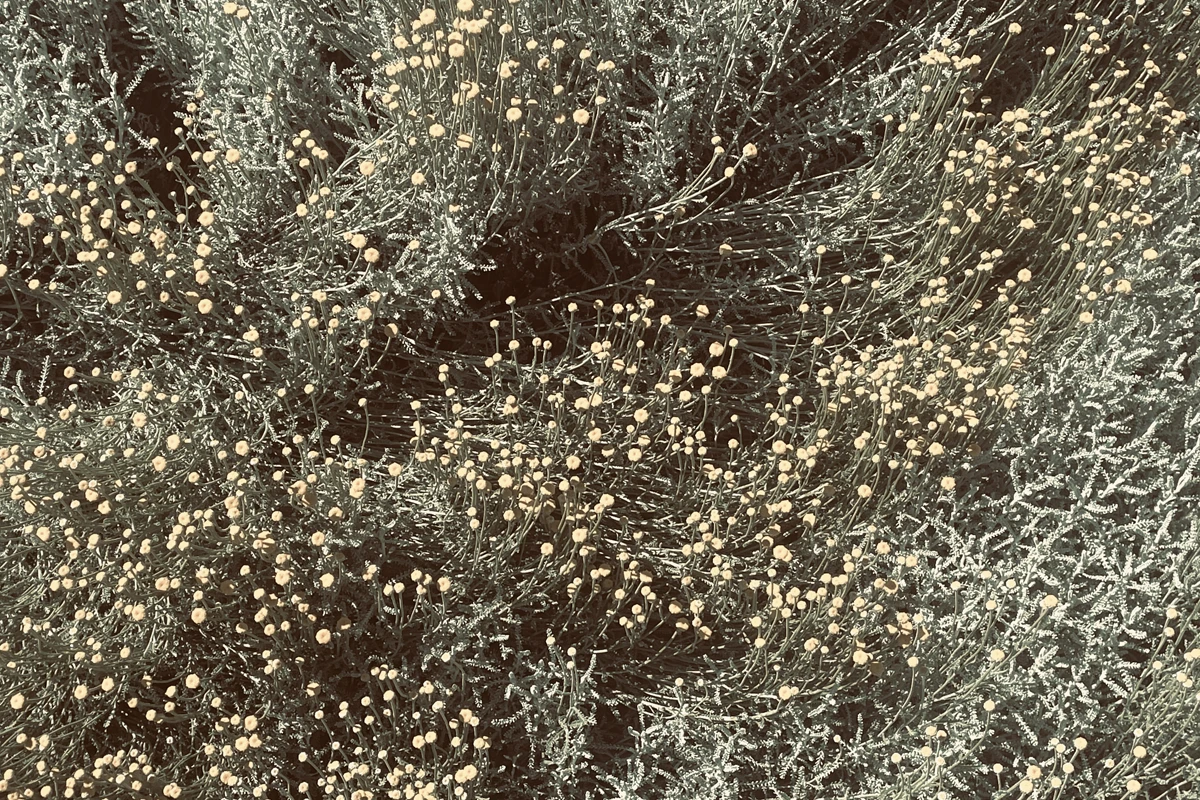

Ladybugs hide among the spikes on the plants and get wet with dew – they are voracious about plant aphids and work as pest controllers. The purple orchid blooms in the thermophilous forest and meadows in spring. The hornet is both an enemy and an ally: it loves grape berries but also wasps, which devour grapes.

Green manure is applied to alternating rows each year with wild peas and fava beans. Deer graze on these herbs but also on vine shoots. In the mid-1990s, a herd of deer escaped from a farm in the Savona area: today, repopulation occurs in the context of progressive human depopulation. Deer hide in the fields, becoming invisible in the mottled coat of the cereal cover: the fawns emit no odor to protect them, their mothers stay away and only approach to feed them. Together with the wild boar, the deer is the wolf’s prey. The wolf also likes grapes – in the La Raia valley, you can find wolf droppings composed entirely of grape berries, a source of vitamin C.

Red partridges sleep on rural houses roofs to avoid being killed by foxes, which eat wild roses. The owl nests in an old cherry tree among the vines near the cellar; the bat in a piece of detached plaster. In the canals and streams here at the base of the Apennines, you can find the Italian freshwater crayfish. These are threatened by exotic species spreading in the Po Valley and preyed upon by the grey heron.

The kestrel and the birds: the Holy Spirit technique

In the air, the hunting falcon, the kestrel, uses “the Holy Spirit technique”: it flaps its wings and keeps its tail spread, creating a vortex that holds it in a fixed point in the sky while scanning the ground for its prey. The kestrel’s eyes are sensitive to ultraviolet light, targeting the small rodents that mark the ground with their urine – the crystals of which reflect ultraviolet rays. The kestrel sees a network of tracks on the ground and focuses on these lines, hunting efficiently without wandering aimlessly over the field. Meanwhile, in the hedges, the fight between the snake and the green lizard continues.

Energy sustainability: wind turbines, solar panels, and kilowatts

La Raia is also an inn, a former post station on the salt route. “From an energy sustainability point of view, we would have liked to do more. Wind turbines do not spoil the landscape, quite the opposite. If it had been up to me, I would have placed a turbine capable of generating 250 kilowatts with a diameter of 45 meters on top of the hill. We are not bound by landscape constraints, but the next day I would have received legal notices and complaints. The turbines off Sardinia and Corsica make sense – but they are not good for fishermen because with the turbines and the associated underwater cables, you create a no-fishing zone. In Germany, they have shut down nuclear reactors and avoid saying how many regasification plants have been activated. Gas is not as polluting as oil and coal, but it is not zero impact.”

“In Italy, we have windy spots. Around Sardinia, around Puglia, in Trentino-Alto Adige. They say solar panels are ugly. Wind turbines are ugly. Nuclear is dangerous. What do we do? A coal mine behind your house? On the roof of the Inn, on the slopes hidden from view, we have installed about 30 kilowatts of photovoltaic. At Borgo Merlassino, another 30 kilowatts. At Serralunga d’Alba, at Tenuta Cucco, we have a project to build a hotel similar to La Raia Inn. There we are in a historic center, a UNESCO site. They don’t allow black panels, but they allow colored ones. The colored panel costs twice as much and yields thirty percent less.”

Barbera wine for breakfast

At La Raia Estate, eight hectares are cultivated with Barbera, a legacy of the sharecroppers who farmed these lands in the nineteenth century. The lands belonged to Genoese families, noble families. In the morning, the sharecropper would eat bread and cheese dipped in Barbera. Today, the cellar produces red wines. The variety of grapes grown determines the quality of the wine, which also depends on how the vines are cared for, how the grapes are treated after harvest, and the winemaking process.

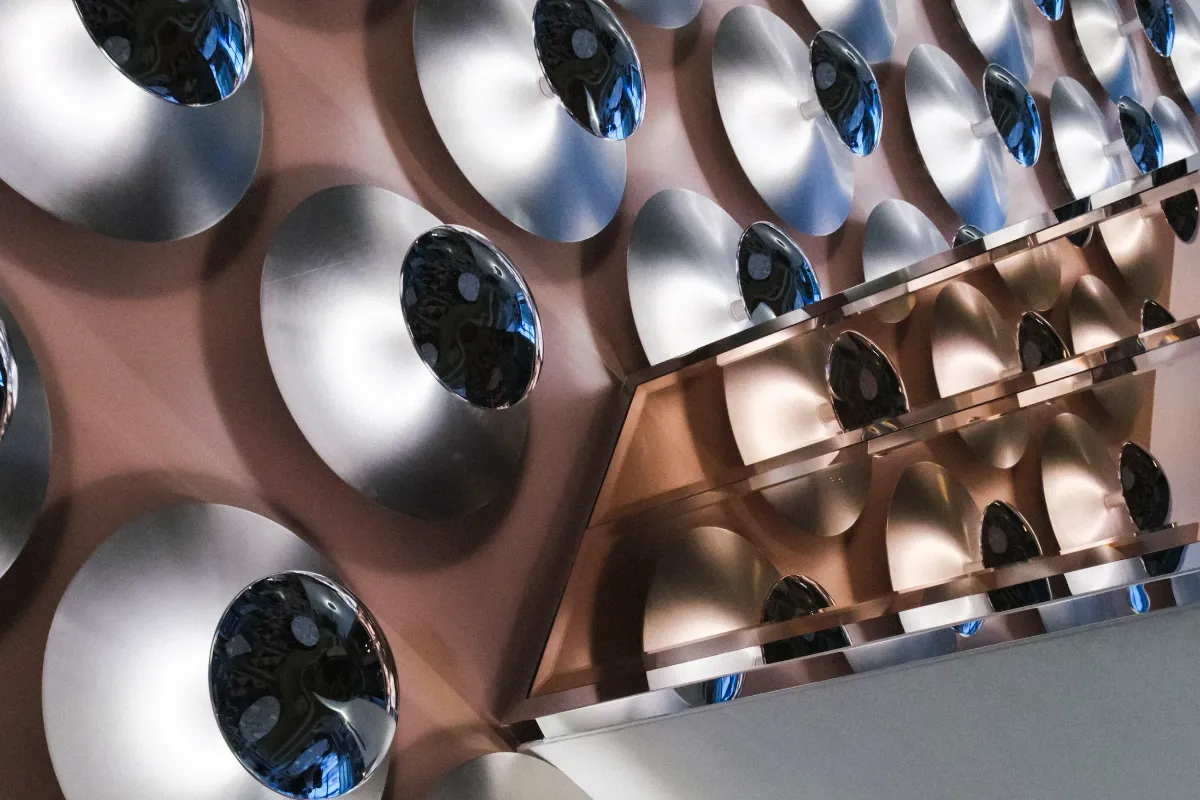

The Bee Palace, by Adrien Missika

The Bee Palace is a work by Adrien Missika, created in 2018. The architecture is designed for pollinating insects, particularly nomadic bees – bees that do not produce honey. There are 2000 holes, each with a depth of approximately three centimeters, allowing the insects to feel both protected and exposed to light. The holes vary in diameter and are drilled into slabs of Luserna stone – the same stone used for the Mole Antonelliana. The hardness of this stone permits the cutting of thin sheets, almost like leaves. Nearby the Bee Palace, there are aromatic herbs – such as wild sage. To construct the Bee Palace, a central cylinder was laid on deep foundations. We are near a lake, and the soil is soft. The ground, fluid and bearing the weight of the inverted pyramid, sustains the structure.

Gavia, princess of the Franks, via Monserito comes from the French language Mon Chere – the oaks and white hornbeam

In the sixth century, the princess of the Franks was fleeing from her father, King Clodomir. The girl’s name was Gavia, and she arrived in these hills. The French troops followed her and found her – but the Queen of the Goths came to her protection. She provided Gavia with an army for her defense and named her lady of these lands behind the Ligurian mountains. The oldest street in the village of Gavi is via Monserito, derived from the French Mon Chere. In honor of the girl from beyond the Alps, the farmers named the grape variety Cortese, which today produces the white wine of Gavi.

Whether it is the present or the future, the oaks will continue to live for up to 500 years. They will live alongside the ashes and white hornbeam. The acorns will be taken by birds as food; they will hide them in furrows of soil like food stores, sometimes forgetting them. The forest will spread again. The burrows of the badgers will bring air to the extensive root systems of the canopies. Dormice will sleep in their trunks, while the woodpecker will drill into the poplar wood.

Carlo Mazzoni

Fondazione La Raia

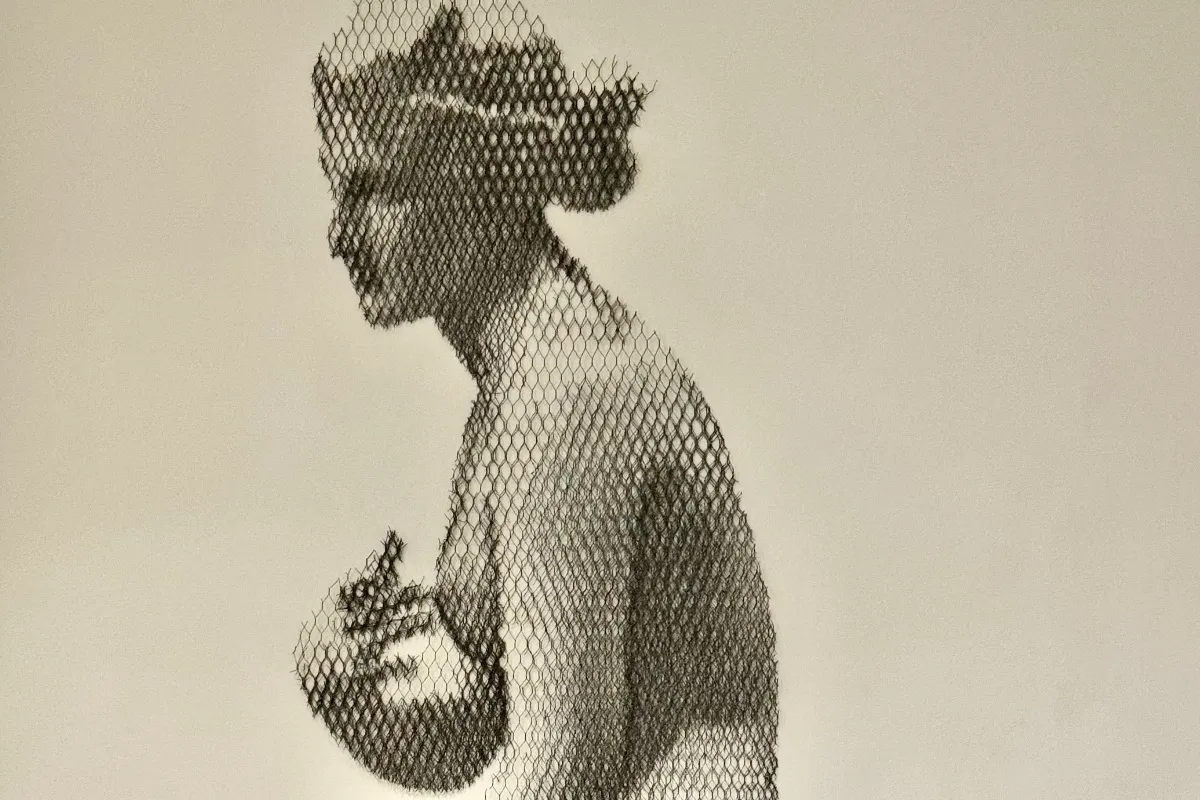

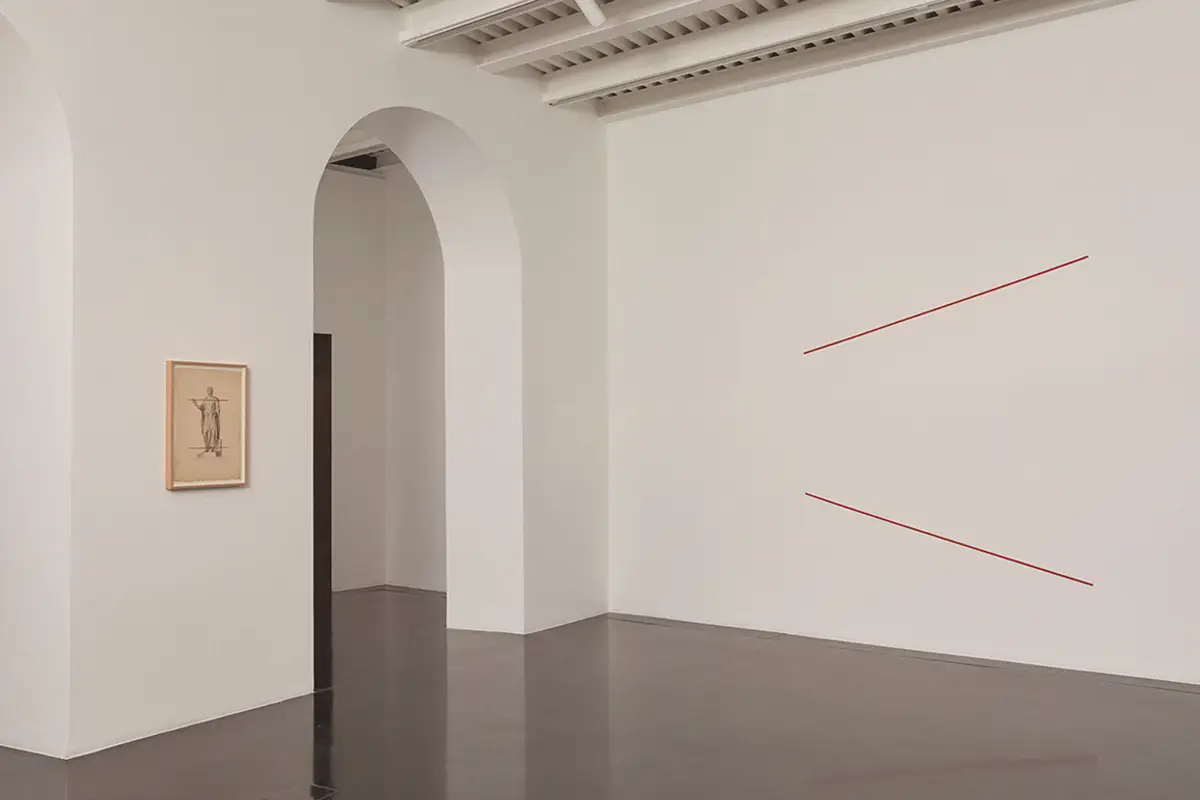

Fondazione La Raia develops themes consistent with the approach that the Rossi Cairo family has given to the homonym biodynamic farm over the past two decades, working in sync with the Gavi’s environment. In the past ten years, the natural theme has been a core issue for La Raia, which has dedicated ten works by international artists to the environment and biodiversity. The activity started with the Nel Paesaggio project: artists, philosophers, agronomists, photographers, and architects were invited to live and experience the vineyards, fields and woods of La Raia, and offered, through interventions and works of art, opportunities for knowledge and a new identity around Gavi.