The slow logic of hospitality: art, identity, and the contemporary Grand Tour

In the Tridente district, contemporary artworks spread across corridors, ceilings, and rooms — part of a hospitality project rooted in Basilicata and embedded in the living texture of central Rome

Art, hospitality, and the contemporary Grand Tour

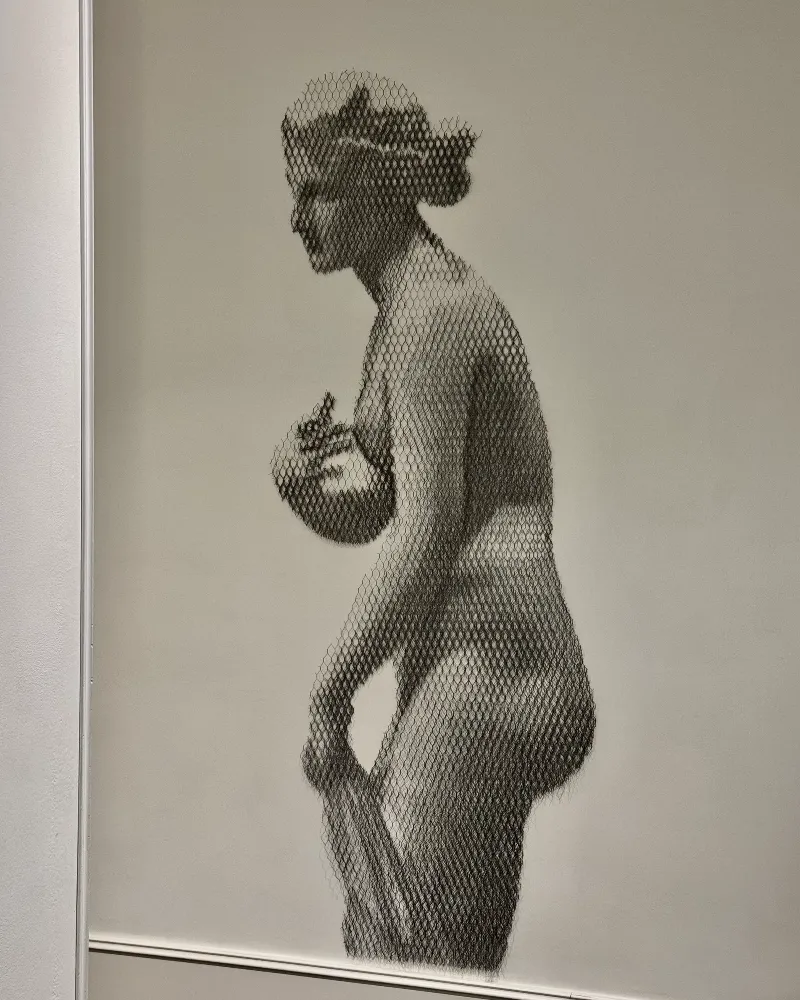

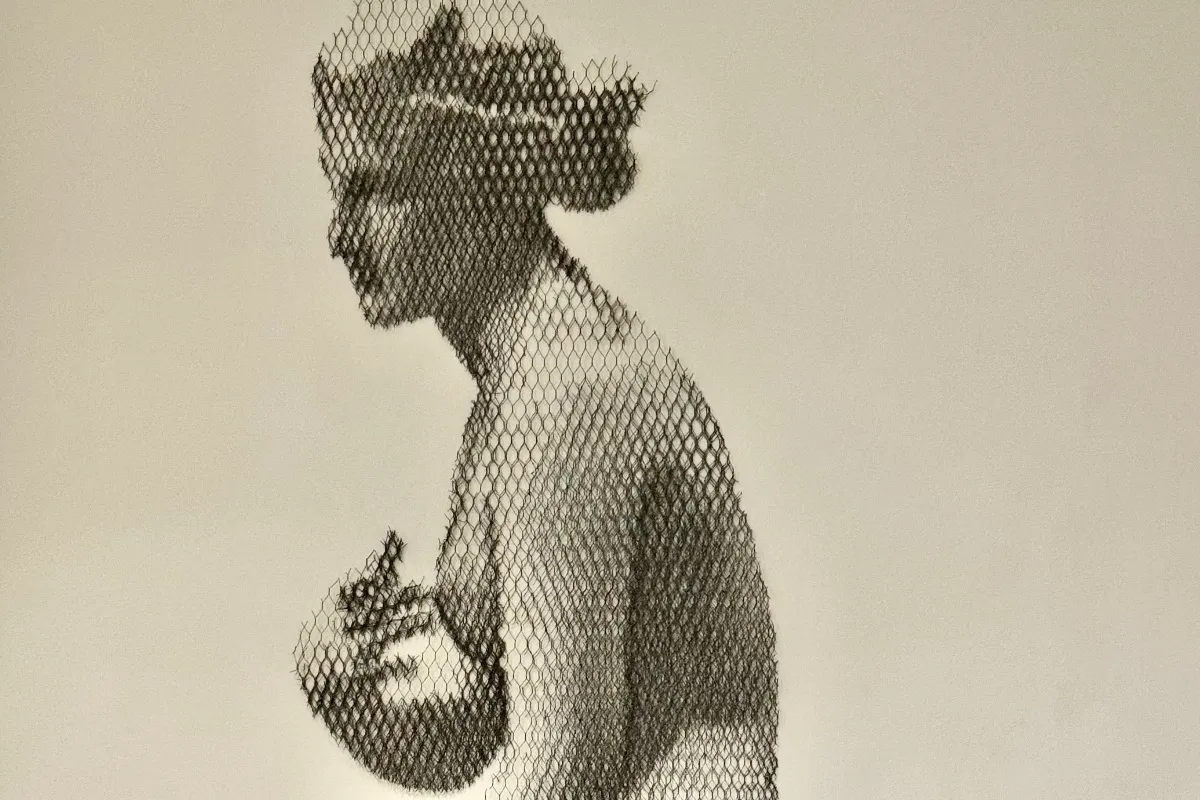

Hundreds of paper butterflies, cut by hand and pinned together, trace the outline of a map on one of the hotel’s walls. The borders shift depending on how long you look. Michael Gambino — an Italian-American artist trained first in biology, then at the Accademia di Brera — builds his cartographies from materials that resist permanence: paper, repetition, the suggestion of flight. His maps don’t claim territory. They question it. And in a place like this, where people arrive from elsewhere and leave again within days, that questioning feels less like a conceptual gesture and more like a precise description of the experience of travel itself.

This is an appropriate place to begin, because Elizabeth Unique Hotel is itself a kind of threshold. Located in Rome’s Tridente district, a short walk from Via del Corso and just behind the Bulgari Hotel, the property occupies one of the city’s most layered and mobile neighbourhoods — a compact area where historical sediment and contemporary commerce, fashion, and tourism coexist in continuous movement. Outside, the rhythm is one of transit and proximity. Inside, a different logic takes hold: spaces unfold as a sequence of encounters, where contemporary art plays a structural role in shaping how guests perceive and move through the building.

The hotel belongs to the Elizabeth Group, an Italian hospitality company with roots in Basilicata, with properties in Rome and Venice. At Elizabeth Unique Hotel, hospitality is conceived as an experience built through continuity — with a family history, and a cultural ecosystem that extends well beyond the check-in desk. That ecosystem takes its most visible form through an ongoing collaboration with Galleria Russo on Via Margutta, one of Rome’s historic streets for artists’ studios and galleries, located a short distance from the hotel itself.

The collaboration with Galleria Russo

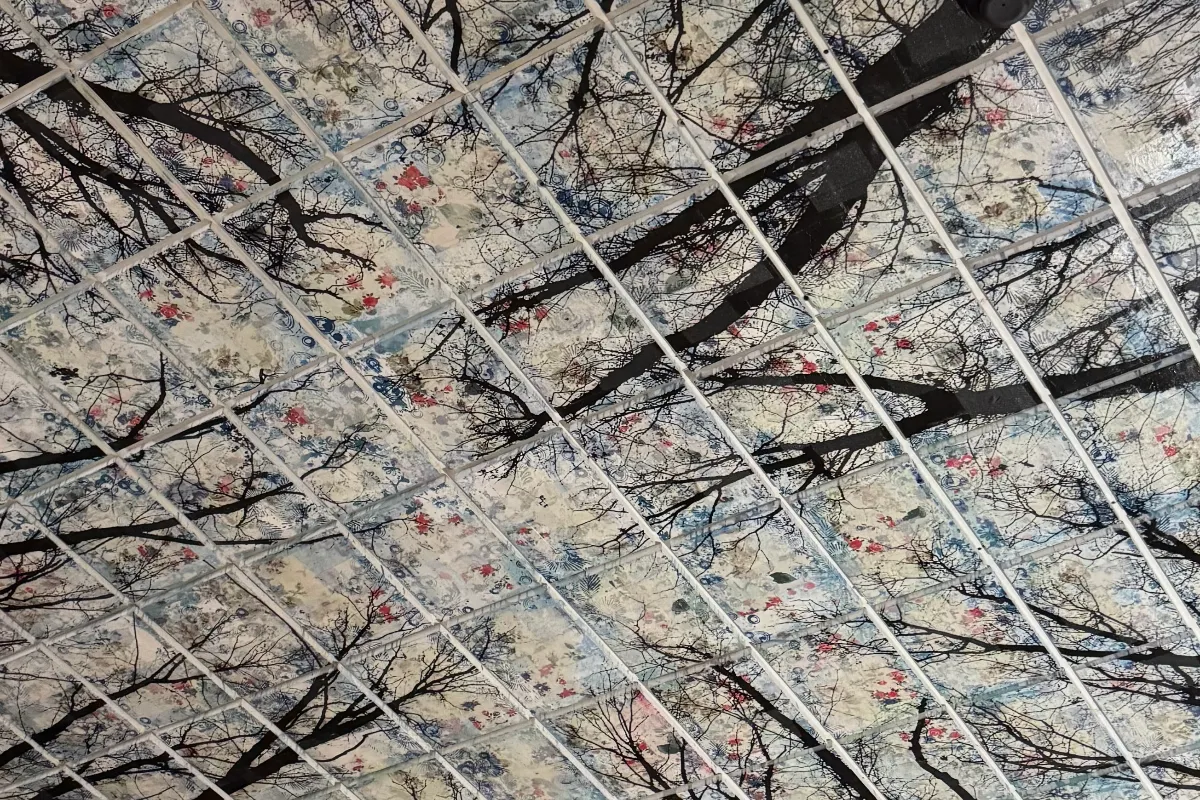

The collaboration with Galleria Russo is an active, evolving relationship. Works selected by the gallery are installed throughout the hotel, in a dedicated exhibition space, but distributed across common areas, corridors, guest rooms, and ceilings. Art is encountered while moving, waiting, or returning: it becomes part of the rhythm of daily gestures rather than an isolated destination. The result is an environment where hospitality and contemporary artistic research coexist without hierarchy.

Via Margutta, historically associated with painters and sculptors, continues to function as a micro-territory of cultural production within the city. By hosting works by artists represented by the gallery, Elizabeth Unique Hotel positions itself as part of this existing network rather than as a detached destination. Guests are temporarily inserted into a system that already circulates between private, commercial, and exhibition contexts. In this sense, the hotel operates as a threshold: not a container of art, but a place where artistic practices remain embedded in urban life.

The wish to be part of a community emerges here not as a declaration, but as a spatial condition. There are no explanatory panels, no curatorial texts mounted beside the works. Art accompanies movement, allowing observation to remain optional, personal, and unmediated.

The image of the tree in Manuel Felisi’s work

Among the artists whose works recur throughout the hotel, Manuel Felisi occupies a central position. His practice unfolds in the space between painting, photography, and collage, often taking the form of layered installations that explore how time accumulates on surfaces and in images. Felisi trained at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera, and his work has long addressed themes of memory, transformation, and duration — the way things persist not by remaining unchanged, but by leaving traces.

Trees are a recurring subject in his visual language. Rendered as bare silhouettes or fragmented forms, they function less as landscape elements and more as archetypal figures that belong to a shared cultural memory — images so familiar they seem to have always existed, independent of any specific place or season. Within the hotel, Felisi’s trees appear in large-scale compositions on walls and ceilings, introducing a displaced form of nature into an enclosed urban interior. The tree becomes a symbolic anchor: a figure of continuity and persistence in a space defined by passage and impermanence.

This approach aligns with a broader notion of sustainable art understood not as environmental messaging, but as attention to cycles, stratification, and the slow life of shared imagery. Felisi’s installations do not simulate nature; they recall it as an idea that survives through repetition and memory. In a city built of stone and density, this visual return of something organic subtly reorients the experience of being inside.

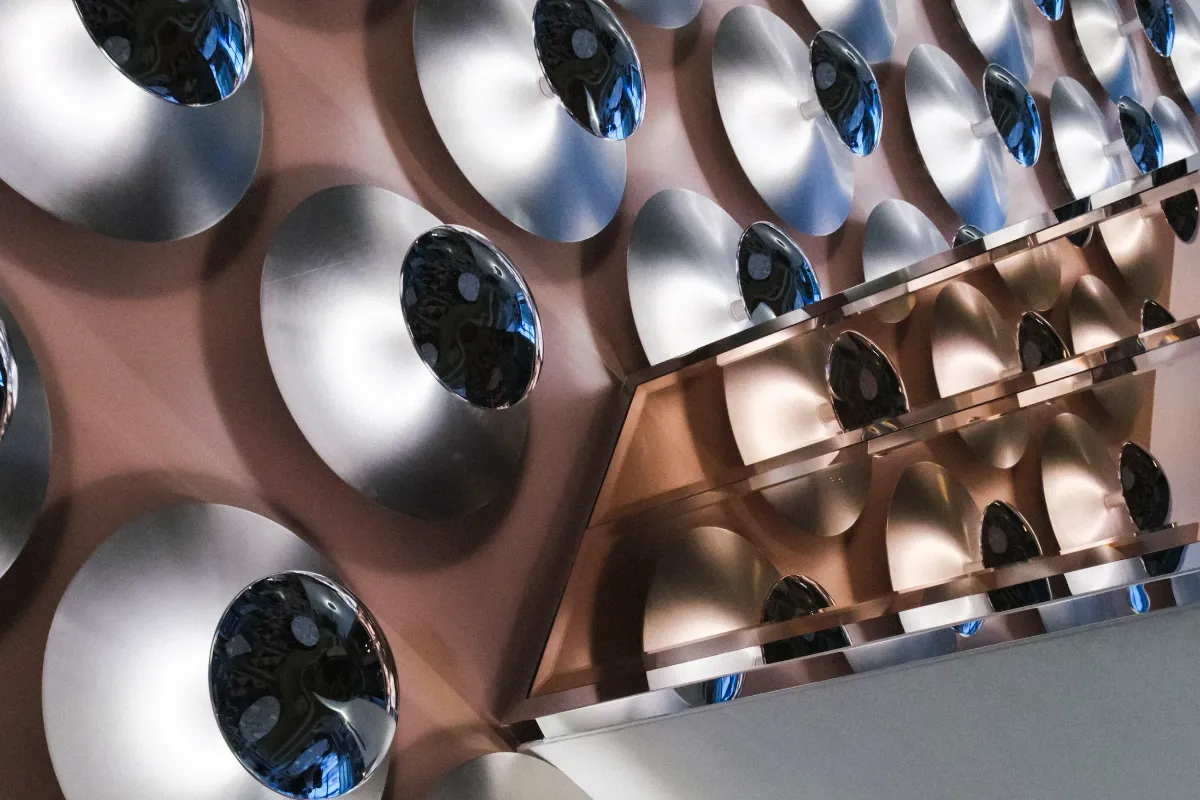

Ethics and aesthetics in Enrico Benetta’s typographic constructions

A different material language characterises the work of Enrico Benetta, whose installations are built from metal letters derived from the Bodoni typeface. Benetta trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice, graduating in Decoration, and his practice has developed across painting, installation, and sculptural forms. What connects these different modes is a sustained interest in how visual form carries cultural weight — how a shape can mean before it is read.

In his work, typography is detached from its conventional communicative function. Letters are multiplied, layered, and assembled into dense visual fields that occupy entire walls and surfaces. Bodoni — a typeface historically associated with Italian printing culture, with a formal elegance that carries centuries of editorial and institutional memory — becomes both material and reference: a structure that holds history in its proportions. Installed within the hotel, Benetta’s works act as interruptions in the expected neutrality of hospitality design. Language is transformed into pattern, and reading becomes secondary to perception.

The tension between meaning and form that runs through his practice situates it in a dialogue between ethics and aesthetics — where the visual pleasure of a surface coexists with its intellectual and historical resonance. These typographic constructions introduce an abstract dimension to the hotel’s interiors, counterbalancing the organic imagery of Felisi’s trees and reinforcing the plurality of approaches that the space is built to sustain.

Human fragility and the cartographies of Michael Gambino

To return to the butterflies: Gambino’s installations are composed of paper forms, cut by hand and assembled into clusters that trace geographic shapes. These configurations resemble maps — familiar in their outlines, unsettling in their instability. The butterfly, traditionally associated with transformation and ephemerality, becomes here a unit of measure for territories that are provisional rather than fixed. Borders drawn in paper and pins do not hold. They suggest that geography, like memory, is always on the verge of dispersal.

Gambino’s background spans both science and art — biology first, then visual arts at Brera — and this dual formation informs a practice that is methodical in its execution and quietly poetic in its effect. Within the hotel, his installations resonate with the specific experience of travel and transience that defines a guest’s relationship to any temporary dwelling. Representations of geography built from fragile, handmade elements mirror the layered, unstable identities of those who pass through.

These cartographies do not assert control over space. They question it, gently and persistently. The concept of human fragility is embedded in both material and form — in the paper, in the repetition, in the suggestion of wings about to move — making Gambino’s works among the most quietly affecting presences in the hotel’s dispersed collection.

DonnaE Bistrot and the translation of Basilicata into the city

Elizabeth Unique Hotel is part of a broader portfolio developed by the Elizabeth Group, whose ownership remains closely tied to its regional origins in Basilicata. This connection is not merely biographical; it informs the group’s approach to hospitality at every level, emphasising continuity, family memory, and long-term projects over rapid expansion or rebranding. The hotel is conceived as something built over time, not assembled for a market. The hotel is also a member of Design Hotels within the Marriott portfolio

The hotel’s narrative extends into its culinary space through DonnaE Bistrot. The name refers to Elisabeth, the grandmother of the owning family, establishing a direct and personal link between family history and contemporary hospitality — the kind of connection that resists the anonymity of branded food and beverage concepts.

Food becomes another layer of the journey the hotel hosts, connecting Rome with southern Italy through raw materials, preparation, and memory. DonnaE Bistrot operates as a complementary space to the art-filled interiors — reinforcing the same idea that runs through every element of the property: that hospitality, at its most considered, is not a singular narrative but an accumulation of experiences, each rooted in something real.