Manila Hemp is better known as Abaca Fiber: what is it?

The Sustainable Alternative to Glass Fiber: Manila Hemp (aka Abaca Fiber) – tensile strength, seawater resistance it’s willing to surpass hundreds of millions by 2030

Manila hemp (abaca fiber): the natural high-strength fiber gaining global relevance in sustainable materials

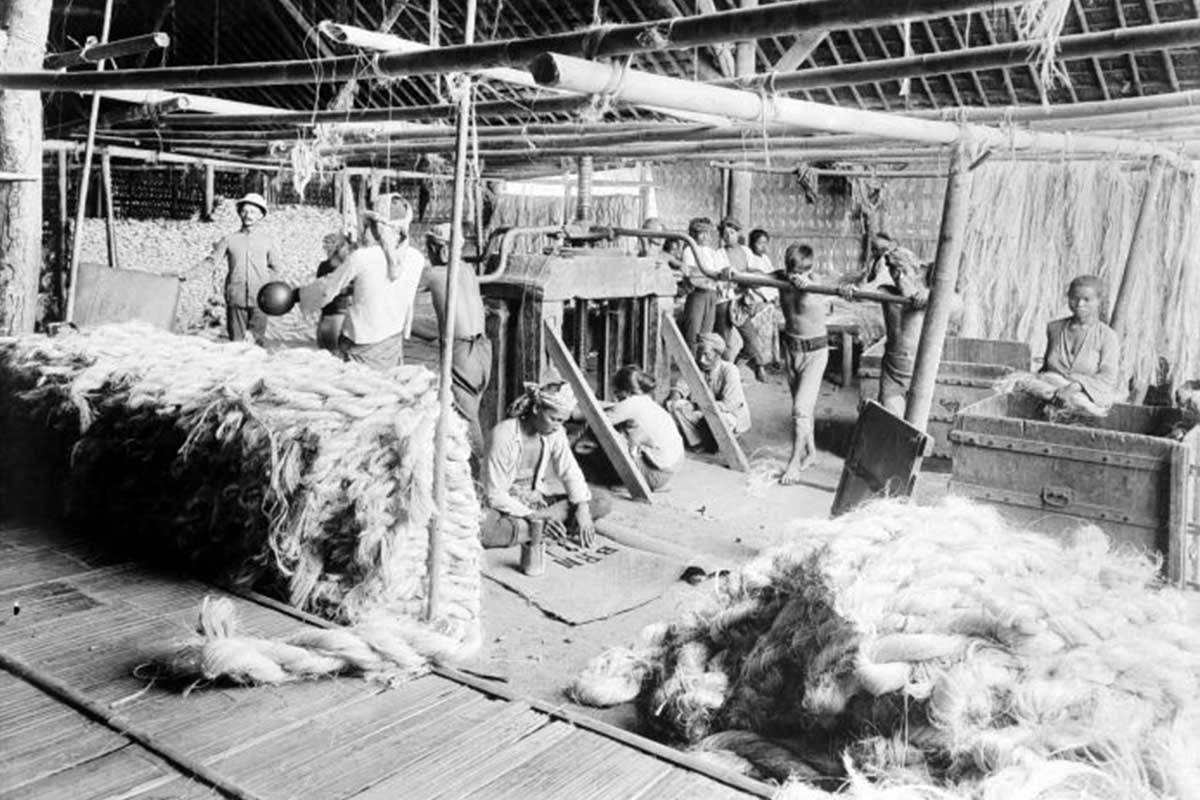

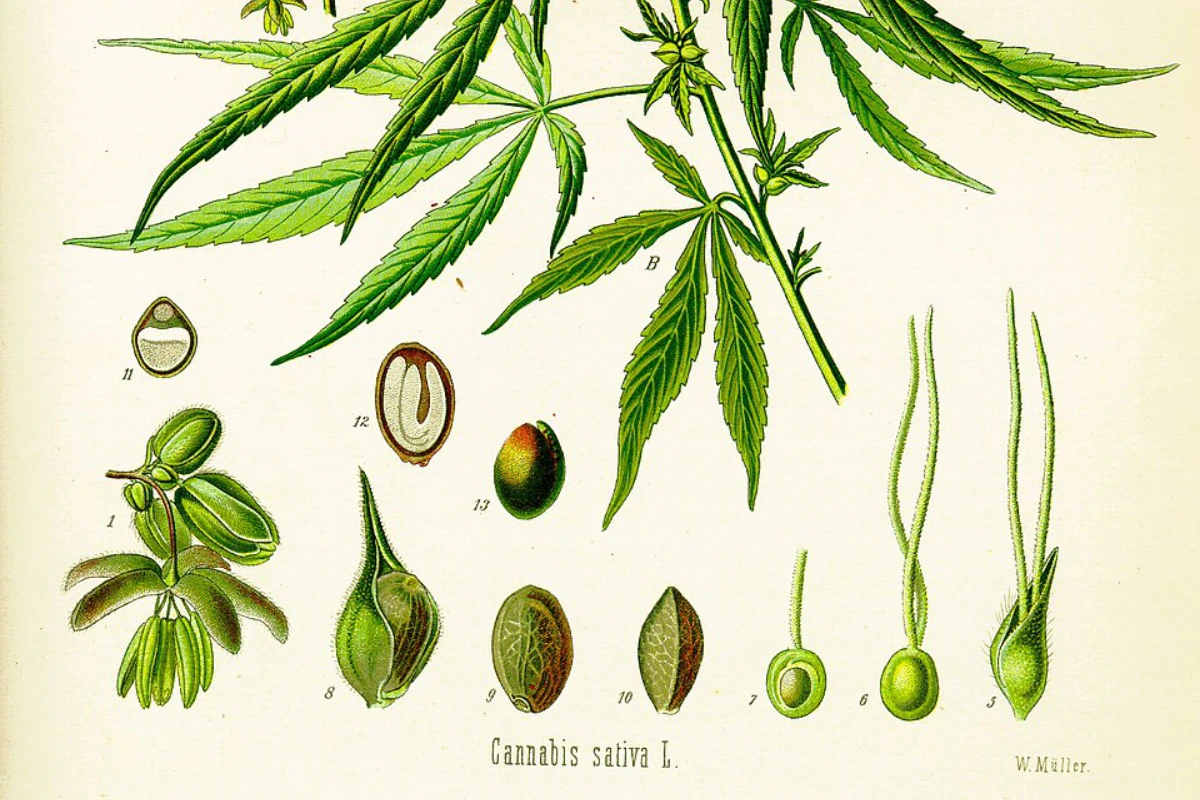

Hard fibers such as Manila hemp – internationally known as abaca fiber – it’s a fiber extracted from Musa textilis, a plant that develops numerous tall stalks from a central root system. These stalks, reaching up to eight meters, are stripped manually or mechanically to obtain long, resilient fiber bundles. Abaca fibers display colors ranging from white to deep brown, red or purple, and their outstanding mechanical strength is linked to their high cellulose content, favorable microfibril alignment and structural properties that enable them to perform under significant stress. As a result, abaca has become a promising option for components that require both flexibility and durability.

Abaca fiber’s unique mechanical advantages and its expanding industrial applications in 2025

For over a century, Manila Hemp has served industries that rely on robust materials such as ship rigging, ropes, twines and specialty papers. Its pulp is essential for currency, filter papers, vacuum bags, tea bags and premium stationery. In the last decade, however, abaca has entered a new phase of relevance thanks to its potential as a reinforcement for composite materials. It is increasingly used in automobile interiors, trim components, bolsters and panels where low weight, tensile strength and acoustic performance are crucial. The construction industry is also experimenting with abaca composite boards and panels as part of a broader transition toward sustainable reinforcement materials.

Production remains largely artisanal in the Philippines, where most farmers use traditional planting material and manual decortication methods that restrict yield and consistency. The textile sector recognizes abaca’s breathability and moisture-wicking qualities, yet its difficulty in weaving and its tendency to wrinkle prevent its adoption in large-scale apparel manufacturing. These limitations highlight the gap between abaca’s natural potential and the industry’s current capacity to process it efficiently.

Why abaca fiber is emerging as a sustainable replacement for glass fiber in automotive and construction industries

The global shift toward renewable materials has prompted a reassessment of natural fibers as substitutes for glass and carbon fibers. Abaca stands out because it combines high specific strength with very low density, making it ideal for fiber-reinforced polymers that aim to reduce overall component weight. Lighter automotive parts contribute to lower fuel consumption, and the use of natural fibers avoids the toxic emissions associated with synthetic fiber production. Abaca also demonstrates remarkable resistance to seawater and maintains excellent mechanical behavior under flexural stress, qualities that make it suitable for both land-based and marine applications.

Hybrid composites that blend abaca with glass fibers reveal improved ductility and flexural performance, although the resulting materials lose some of the biodegradability that makes abaca attractive to circular-economy industries. When engineers optimize treatments and coupling agents, abaca composites can reach performance thresholds comparable to synthetic alternatives while presenting a far more favorable environmental profile. This positions the fiber as a serious candidate for next-generation sustainable composite materials.

Environmental benefits of abaca cultivation: how Manila hemp restores degraded landscapes and increases climate resilience

Much of the Philippine landscape has been affected by decades of monocropping, erosion and land degradation. Abaca cultivation has proven to be one of the most effective interventions for restoring ecological balance in these areas. Its root system stabilizes the soil on steep slopes, reduces sedimentation in rivers and coastal zones, and improves the water-holding capacity of the soil. Communities in abaca-producing regions have observed fewer landslides and less severe flooding as the crop spreads across previously degraded lands.

From a climate perspective, abaca cultivation requires minimal energy compared to synthetic fiber production. Its carbon footprint remains low when residues are reintegrated into the farming system, and its natural biodegradability at the end of its life cycle gives it an ecological advantage over petroleum-derived materials. For this reason, abaca is increasingly regarded as a climate-positive fiber aligned with global decarbonization strategies.

Challenges facing abaca farmers and the urgent need for modernization, fair value chains and technological innovation

Despite its growing global relevance, the abaca industry still faces structural challenges. Farmers often work with outdated tools and labor-intensive extraction methods that slow production and compromise fiber quality. Inconsistent grading, contamination during drying and harvesting of immature stalks contribute to unpredictable supply. Many growers sell their harvest at low prices because they lack bargaining power within the value chain, and the absence of organized support systems exposes them to market fluctuations and exploitative practices.

Modernizing this sector requires improved access to efficient decortication machinery, training in standardized processing methods and the development of cooperative networks that allow farmers to negotiate fair contracts. Ensuring the availability of disease-resistant varieties and updated agronomic practices would also strengthen the industry from the ground up. Creating a fair and transparent value chain is essential not only for ethical production but also for guaranteeing that international industries can rely on a stable supply of high-quality abaca fiber.

How building a global abaca industry can meet rising worldwide demand for sustainable high-strength fibers

As the global market accelerates its transition toward bio-based materials, abaca fiber is experiencing a renewed wave of interest. Countries with tropical climates have the potential to join the Philippines and Ecuador in cultivating abaca at scale, contributing to a more diversified global supply. Mechanized plantations and modern processing facilities demonstrate that expansion is achievable when investment and agricultural expertise converge. If producing countries adopt new technology and improve processing standards, abaca could become a leading natural alternative to synthetic reinforcement fibers across multiple sectors, including automotive manufacturing, construction, specialty papers, packaging and consumer goods.

The growth of the abaca industry also leads to environmental gains, since the crop thrives in agroforestry systems that rehabilitate degraded land, restore biodiversity and support climate resilience. The future of abaca lies in uniting technological innovation, environmental stewardship and equitable development strategies—an approach that reflects the priorities of both emerging markets and global sustainability frameworks.

Education, research and global awareness: abaca’s role in shaping future sustainable materials and community-centered economies

Academic institutions and research centers are dedicating increasing attention to abaca as a model of how natural fibers can drive environmentally and socially responsible innovation. Courses and webinars focused on land use, rural development and sustainable manufacturing now highlight abaca as a case study in balancing ecological restoration with economic opportunity. Researchers view the industry as a living example of how renewable materials can replace high-impact synthetics while supporting the livelihoods of local communities.

These educational efforts help build greater international awareness of the fiber’s potential and contribute to shaping policies and market strategies that will define abaca’s role in the sustainable industries of the future. The material’s relevance is no longer limited to traditional uses; it now stands at the crossroads of technology, ecology and global development.