Norbert Niederkofler and the short supply chain that changes the mountain

From the origins of Cook the Mountain to three destinations – Atelier Moessmer, Ansitz Heufler and AlpiNN – Norbert Niederkofler has built a model rooted in Alpine short supply chains and cultural heritage

How ‘Cook the Mountain’ rewired Alpine fine dining and its supply chains

Norbert Niederkofler has built a vision. He calls it Cook the Mountain, a strict choice to practice fine dining with what the mountain itself provides—season after season, without importing “easy” ingredients. It is a philosophy that has, over time, reshaped supply chains, preservation methods, and even the relationship between chefs, farmers, and herders.

Today, that vision takes form in three places telling a single story: Atelier Moessmer Norbert Niederkofler in Brunico (three Michelin stars and a Green Star), the newly restored Ansitz Heufler manor in the Anterselva Valley, and AlpiNN at the summit of Plan de Corones, beside the LUMEN museum. Three different expressions, one project: demonstrating that a transparent and sustainable short supply chain can generate identity—and a future.

Inside Atelier Moessmer: from a wool mill villa to a three-star laboratory

The Cook the Mountain philosophy began as practice and then as a manifesto: regional, seasonal, no greenhouses, no out-of-territory products. This means giving up olive oil and citrus fruits, using very little salt, and finding alternative sources of acidity (such as grapes or berries), preserving through fermenting, drying, and smoking, and above all, building an operational relationship with those who actually work the mountain. Niederkofler himself has explained that starting in 2008, it took him five years to build a reliable supply chain, to persuade producers and to organize a local economy capable of sustaining the pace of fine dining.

The outcome is a method where the menu is dictated by Alpine biodiversity, by climate and natural rhythms: no tomatoes in winter, no lemons, no foie gras or imported caviar, no exotic shortcuts. It is a cuisine that reduces waste and respects every part of the raw material. “In my kitchen I don’t use olive oil… we use very little salt, and only at the end,” the chef explained when describing the transformation of his style and the birth of Cook the Mountain. The project today also exists as a two-volume book (with photography and 60 seasonal recipes) that gives voice to the human and natural landscape underpinning this philosophy.

Atelier Moessmer, three stars in the villa of wool

The Atelier Moessmer is the present-day home of Niederkofler’s haute cuisine. The restaurant is located in the historic director’s villa of Moessmer, a textile company founded in 1894 in Brunico and still active today as one of the few remaining mills to manage the entire wool cycle (from washing to finishing) on-site, collaborating with major international fashion houses such as Gucci, Chanel, and Loro Piana. The villa sits in a historic park near the city center, preserving objects such as a fabric sample book from the early 20th century—reminders of the link between territory, craftsmanship, and quality.

The villa has a layered history: once the residence of Moessmer’s directors, it was later used until the 1990s as a private home and eventually as an atelier by a South Tyrolean writer. When the Rosalpina—Niederkofler’s previous base—was headed toward a period of closure and renovation, the chef and his brigade saw an opportunity. Rather than dispersing his twenty-five collaborators, he sought to preserve the team by opening a new home for Cook the Mountain in Brunico, just a few minutes from where he lives. The decision, first conceived as a dream when he drove past the villa on his daily commute, became reality after 2022.

The project was fast-tracked: the Rosalpina closed in March 2023, and on July 12 of the same year the Atelier opened its doors, with two preview services for friends before welcoming its first guests on July 14. The timing was crucial: to be considered in the Michelin Guide, a restaurant must operate for at least 100 days before the annual November announcement. By November 14, only four months after opening, Atelier Moessmer received three Michelin stars and the Green Star for sustainability—confirmation of the project’s maturity and coherence.

Atelier Moessmer: the historic villa and the contemporary glass wing

The restoration of Villa Moessmer brought back the warmth of its wooden ceilings, the intimacy of its rooms, and the cadence of its original windows. Yet the most striking addition is the new glass pavilion opening onto the garden: a transparent volume that hosts the open kitchen and counter seating, conceived to make the choreography of cooking visible and directly connected to the surrounding landscape.

This dual identity—textile heritage and contemporary precision—also defines the dining experience. Service is measured, techniques are clean, textiles appear as markers of identity, while wines and fermentations echo the Alpine microcosm. Every morning, the brigade goes out in search of what the mountain can offer that day. From there, the gastronomic performance begins: like a theater troupe, the team moves in calibrated harmony around the stainless-steel open kitchen, each chef at their own station. Guests, seated on stools along the counter that frames the kitchen, watch the spectacle unfold—an audience drawn from around the world to experience Niederkofler’s cuisine.

Beyond this futuristic space suspended within the park, the villa also offers smaller dining rooms, where intimacy and privacy balance the transparency of the glass wing.

The “second creation”: Ansitz Heufler, a 16th-century manor reimagined as an inn

If Atelier Moessmer is the research lab of haute cuisine, Ansitz Heufler is its welcoming counterpart. Set at the threshold of the Antholz/Anterselva Valley in Oberrasen (Rasun di Sopra), the manor dates to 1580 and belonged to the Heufler von Rasen lineage. The landscape frames the project’s rhythm. Ansitz Heufler looks toward Plan de Corones/Kronplatz and sits on the route that climbs to high-meadow trails, the Rieserferner-Ahrn protected area, and the lakes and passes that mark the valley’s upper stretches.

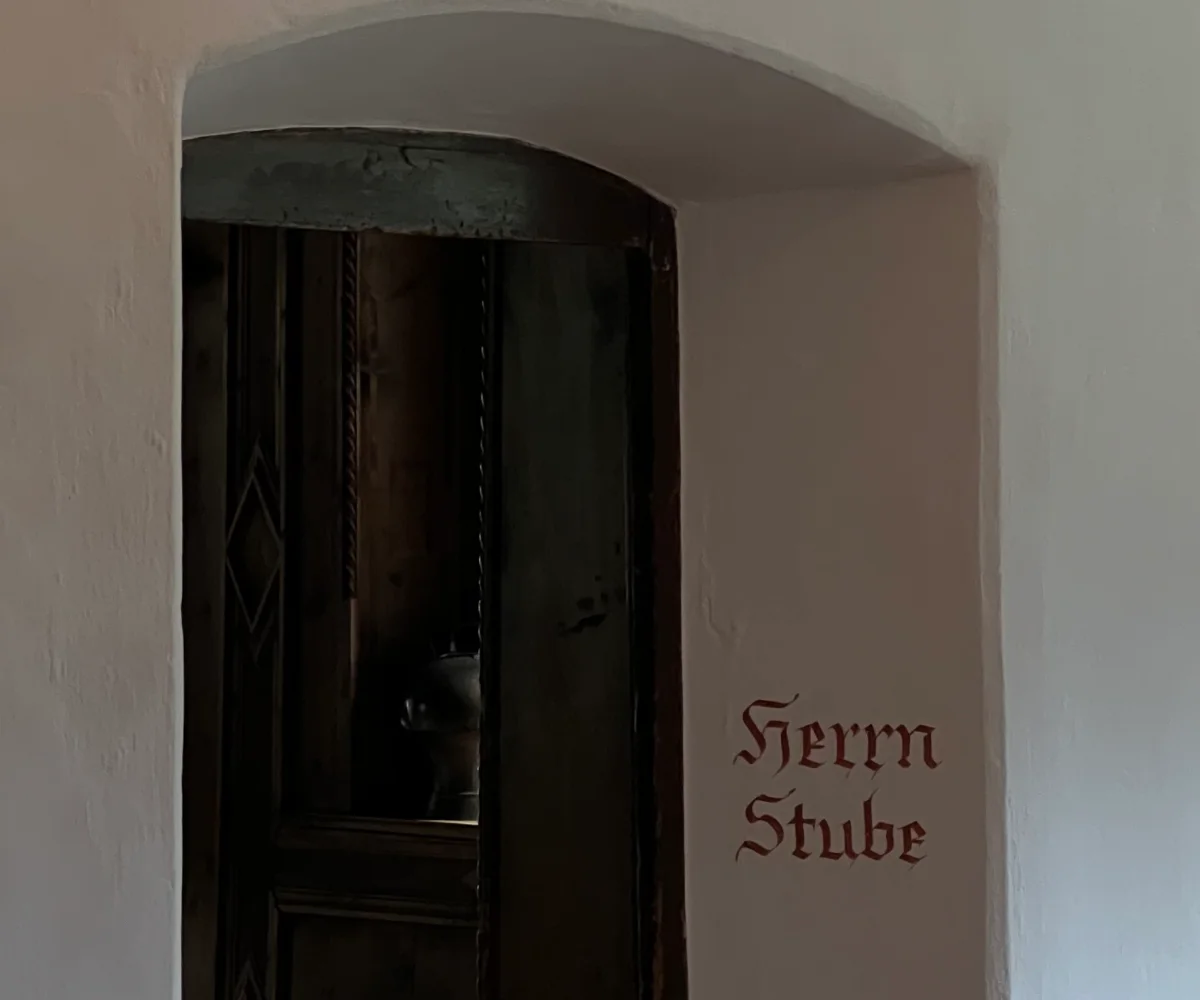

After a philological restoration, the house has returned to life as a small hotel with a trattoria and lounge bar—hospitality woven into history rather than layered on top of it. Inside, the building reads like a primer of Alpine domestic culture. Wood-paneled stuben, hand-carved ceilings and door frames, and the celebrated Hearnstube—a Renaissance parlor centered on a heraldic kachelofen—preserve the atmosphere of an aristocratic home while remaining usable, human, warm. The former Rauchkuchl (smoke kitchen) now hosts the lounge: a nod to the old techniques of drying and preserving that once defined mountain life. The result is not a museum but a living interior, where daily rituals—breakfasts with small-scale dairy, afternoon snacks, a glass by the fire—carry local memory forward.

What is a stube?

But what, exactly, is a stube? The stube is the wood-paneled room typical of Alpine homes in German- and Ladin-speaking areas: historically the only heated room, centered on a large ceramic stove (kachelofen). It was the heart of family life, a place of work and gathering, and over centuries became a status symbol, with carved wood, benches, and decorated surfaces. Often the stove was heated from the adjoining kitchen, making it both efficient and emblematic. To understand the stube is to grasp the cultural weight of Ansitz Heufler’s interiors and their role in Tyrolean life.

The contemporary South Tyrolean trattoria led by Matteo Delvai

The dining room translates Cook the Mountain into everyday terms. Under Norbert Niederkofler’s supervision, Matteo Delvai runs a modern South Tyrolean trattoria: clean techniques, short supply lines, clear flavors. Expect pressknödel, schlutzkrapfen, polenta with mountain cheeses and mushrooms, alongside roasts such as pork knuckle, and sweets like kaiserschmarrn or rice pudding—comfort dishes grounded in the valley’s pantry. Sourcing prioritizes nearby producers; the point is not nostalgia but continuity, bringing the same transparency practiced at Atelier into a format that’s informal and approachable.

Upstairs, ten rooms and suites furnished with local woods and a restrained palette extend the same idea of measured comfort. Mornings open with an alpine breakfast—fresh breads, butter from small dairies, homemade preserves—served to guests. Reading rooms and smaller parlors offer privacy, while the lounge in the old smoke kitchen anchors the social life of the house with charcuterie, cheeses, and a daily soup.

AlpiNN: architecture and design—adaptive reuse, choreography, and view

At 2,275 meters on the summit of Plan de Corones/Kronplatz, AlpiNN is the most panoramic face of Cook the Mountain: a restaurant “suspended” between Dolomites and Alps, conceived as a “living room in the mountains.” It occupies the summit-level shell of the former cable-car station, reworked within the LUMEN complex. Inside the museum’s four floors (about 1,800 m²), AlpiNN shares the same envelope and outlook, including the iconic “Shutter,” a giant mechanical diaphragm that opens to the panorama or closes as a projection screen. Floor-to-ceiling glazing turns the horizon into a constant backdrop.

Day to day, chef Fabio Curreli interprets Niederkofler’s philosophy with straightforward dishes, clean techniques, and mountain fermentations (miso, kimchi, sauces made with local produce).

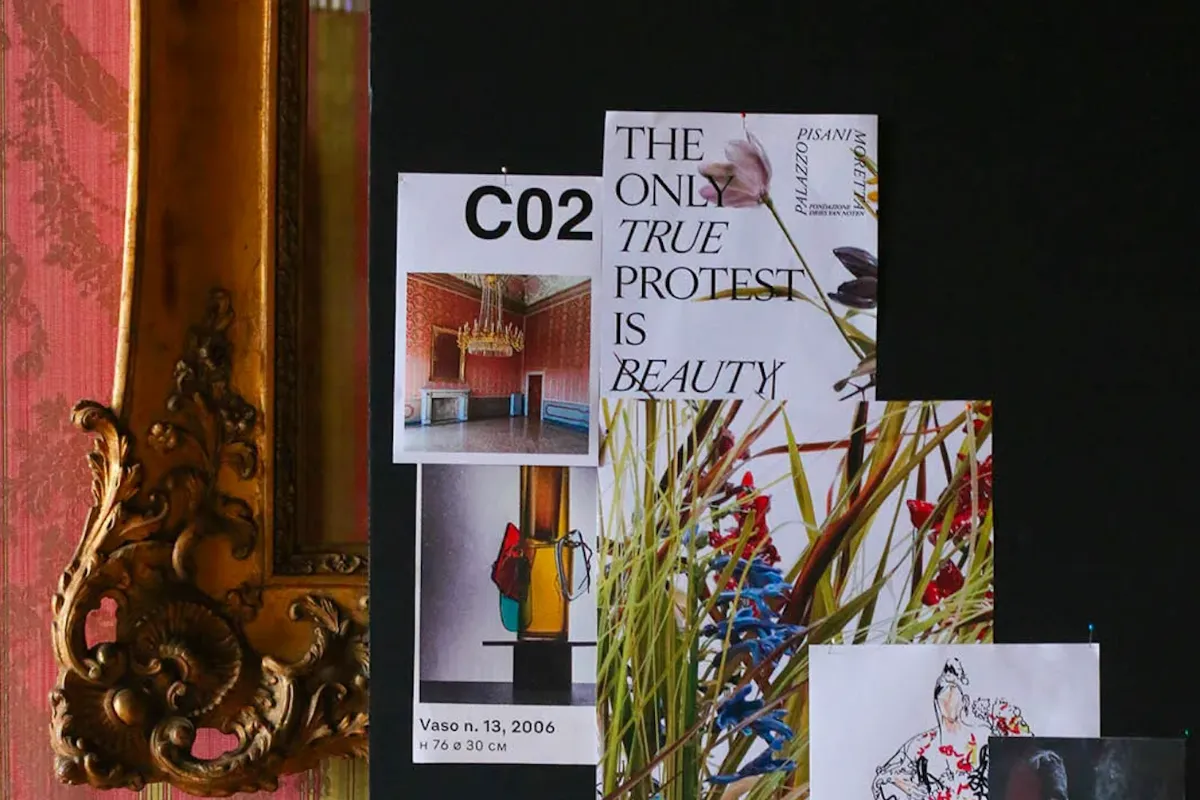

Design by Martino Gamper at AlpiNN: loden ceiling, modular tables, stube chairs

Martino Gamper shaped the interiors of AlpiNN to replace a rigid restaurant typology with a choreography of standing/dining/lounging. Circulation, counter heights, and seating typologies are calibrated to those three postures, keeping service fluid while staging the view as an “ingredient.” The result is a public interior that feels domestic yet works precisely for mountain hospitality—craft-driven, social, and context-led.

Materially, the space privileges local craft and materials. Furnishings made by South Tyrolean artisans put wood at center stage; seating reinterprets the stube chair archetype, modular tables regroup for different service patterns, and lamps ride linear rails to flex with layout changes. Overhead, a ceiling of loden panels (Tyrolean wool cloth) creates a soft, acoustically warm plane—here finished with a water-friendly Japanese technique—while underfoot a larch floor from the Aurina Valley updates traditional Tyrolean parquet. The palette is tactile and place-specific, connecting dining to the region’s material culture.

Spatially, AlpiNN is articulated into distinct yet connected zones. Food Space is the informal bistro heart; The View is a front-row strip of eight tables aligned to the windows for a dedicated tasting experience; and The Lounge extends the “living room” idea with sofas and low tables for aperitifs and pauses between ski runs. Each area shares the same seasonal, locally sourced ethos while using design to modulate tempo, privacy, and perspective on the mountains.

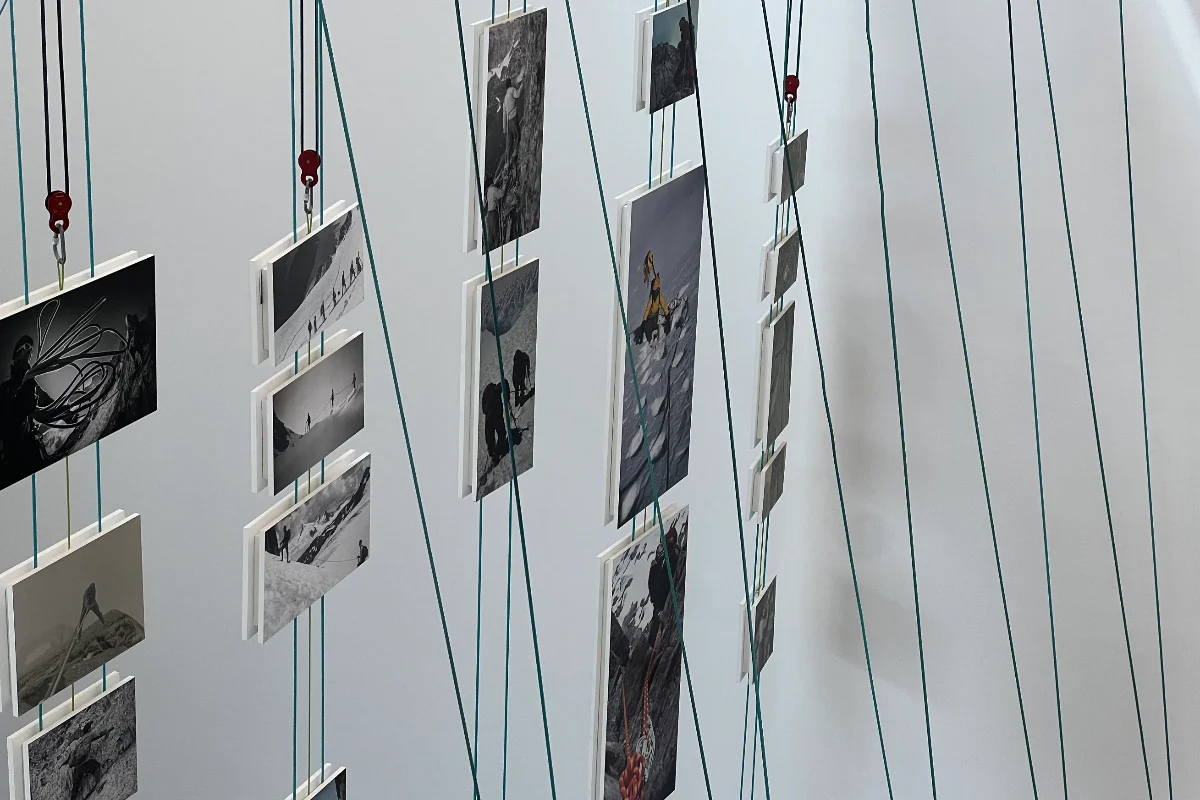

LUMEN next door: photography, landscape, identity

AlpiNN shares its building with LUMEN, the Museum of Mountain Photography: a four-story, 1,800 m² project opened in 2018 inside the repurposed cable car station. It is dedicated entirely to the history and language of mountain photography, from Vittorio Sella’s pioneering shots to contemporary works. Its icon is the “Shutter”, a giant mechanical diaphragm that opens toward the Dolomites or closes to serve as a projection screen. The museum-restaurant combination is deliberate: culture and cuisine as two ways of observing the mountain.

MMM Corones by Zaha Hadid: architecture carved into the mountain

Beside LUMEN stands MMM Corones, the last of Reinhold Messner’s six mountain museums. Designed by Zaha Hadid and opened in 2015, it is embedded in the rock, with four openings like telescopes onto the landscape. Inside, it narrates the culture and history of alpinism. Hadid described the project as “descending into the mountain to explore its caves and cavities, then emerging on a cantilevered terrace with panoramic views.” This is one reason Plan de Corones has become a European crossroads of outdoor sports, design, and culture.

Matteo Mammoli

Plan de Corones/Kronplatz

Plan de Corones/Kronplatz is a mountain shaped like a dome, offering 360° views of Dolomites and Alps. In winter it is one of South Tyrol’s largest ski areas: 121 km of slopes, modern lifts, broad sunny descents. In summer it becomes a terrace for trekking, hiking, and biking, with well-marked trails. The summit is also home to two unique cultural poles: MMM Corones, designed by Zaha Hadid and dedicated to extreme alpinism, and LUMEN. Visitors can also take off for paragliding and hang gliding, and the Concordia 2000 Peace Bell rings out as a symbol of unity.