In Munich, an urban hotel drawn to the edge of a botanical horizon

With its curving volume, The Charles Hotel, extends the essence of the Old Botanical Garden into the city’s fabric, pairing rational architecture with biophilic interiors

The Charles Hotel, a Rocco Forte Hotel – Munich: an urban threshold between Maxvorstadt and the Old Botanical Garden

Approaching from Sophienstraße, the city’s noise dissolves more quickly than expected. The building curves gently along the edge of the Old Botanical Garden, drawing the eye off-axis toward the canopy of trees. The Charles Hotel, part of the Rocco Forte Hotels group, was commissioned in 2005 and opened two years later as a purposeful insertion on the western edge of Maxvorstadt — a hinge between the railway district and Munich’s historic core.

Designed by Munich-born architect Christoph Sattler of Hilmer, Sattler & Albrecht, The Charles Hotel occupies a prominent site within the Lenbachgärten development, a large-scale urban renewal project that mediates between the bustle of the central station and the composure of the city’s museum quarter.

Urban form, façade design, and the architectural language of The Charles Hotel

The hotel’s main volume runs parallel to the edge of the Botanical Garden, following a subtle curvature that shapes the urban frontage while opening framed views toward the greenery. This soft geometry breaks the rigidity of the street line yet preserves continuity with the surrounding residential buildings.

The complex comprises eight above-ground floors and one basement level dedicated to technical and service functions. The ground floor acts as a transparent base mediating between public and private realms: the generous lobby serves as both visual and functional filter, connecting the entrance on Sophienstraße with the park opposite.

Christoph Sattler employs a measured architectural language, recalling Art Deco tempered by German Rationalism. The façades are clad in light limestone — a natural, durable material consistent with Bavarian building traditions. Vertical openings framed by fine mouldings create a rhythmic elevation, subtly emphasized by the curvature of the main frontage.

Interior design philosophy: from architectural rationalism to botanical inspiration

The interior design was developed by Rocco Forte Design, under the direction of Lady Olga Polizzi, in close collaboration with the architect. The group’s approach avoids standardized hotel formulas: each property is conceived as an interpretation of its local setting. In Munich, the adjacent Botanical Garden becomes the conceptual thread — expressed through vegetal tones, natural fabrics, extensive use of wood, and the presence of living plants in public areas.

The result is not decorative but perceptual: the interior prolongs the visual continuity with the park outside. The design language remains rational and disciplined, with bespoke furniture integrated into the architectural framework.

Nearly two decades after opening, the hotel underwent a substantial refurbishment completed in 2025. The project – by Paolo Moschino and Philip Vergeylen, in collaboration with Olga Polizzi – focused on the ground floor, restaurant, and rooms. The intervention respected the building’s original structure while renewing the atmosphere through updated materials and palettes.

In the lobby, a large curved plaster installation by François Mascarello forms a sculptural backdrop to the reception. The new desk is clad in green marble, with pale sandstone flooring beneath. Furnishings are arranged radially, echoing the curvature of the façade.

Florio Restaurant, Munich – architecture, material coherence, and culinary design

The Florio Restaurant occupies the hotel’s principal frontage, directly overlooking the Old Botanical Garden. The 220-square-metre interior is organized into three zones — bar, main dining room, and terrace — unified by clear visual continuity. Axial views align interior perspectives with the surrounding park, while round columns clad in light oak and continuous material surfaces define the space without resorting to ornamental excess.

The restaurant’s language is rooted in material coherence. The color palette echoes the exterior landscape — moss green, olive grey, beige, and ochre. The central bar, faced with Indian Rainforest Gold marble, introduces an organic counterpoint: its flowing veining recalls botanical structures and reflects natural light from the full-height windows, creating a dialogue between mineral and vegetal matter.

Gastronomy and design: contemporary Italian cuisine rooted in Bavaria

Custom-designed furnishings combine wood, brass, and natural textiles. Curved banquettes and sage-green velvet seating follow the geometry of the envelope, while light draperies and potted plants filter daylight and soften the transition between interior and exterior.

Forming the backdrop to the breakfast buffet room, a bespoke hand-painted mural with botanical motifs creates a visual connection to the adjacent garden. On the main dining area, large glass doors open onto the terrace, paved in light stone and furnished with iron tables and chairs.

Local sourcing and sustainable gastronomy

Behind the culinary vision of Florio is Fulvio Pierangelini, Rocco Forte Hotels’ Creative Director of Food. The restaurant offers contemporary Italian cuisine rooted in local and seasonal ingredients.

Florio integrates a local supply network that supports short-chain production and traceable sourcing across Bavaria. Producers are selected for their environmental standards and continuity of traditional practices. The hotel collaborates with Gutshof Polting, a family-owned estate active since 1899, which provides corn-fed poultry, lamb, and trout raised through extensive farming and responsible land management. This approach establishes a direct link between the kitchen and the regional landscape.

Further suppliers include Honest Catch, which cultivates freshwater prawns and shellfish in controlled Bavarian aquaculture systems, and Back Geschwister, a bakery specializing in naturally leavened bread made from regional grains. The system reflects The Charles Hotel’s objective of maintaining transparent supply chains and aligning its culinary offer with sustainable production methods rooted in the local context.

The Charles Spa: biophilic wellness and architectural continuity

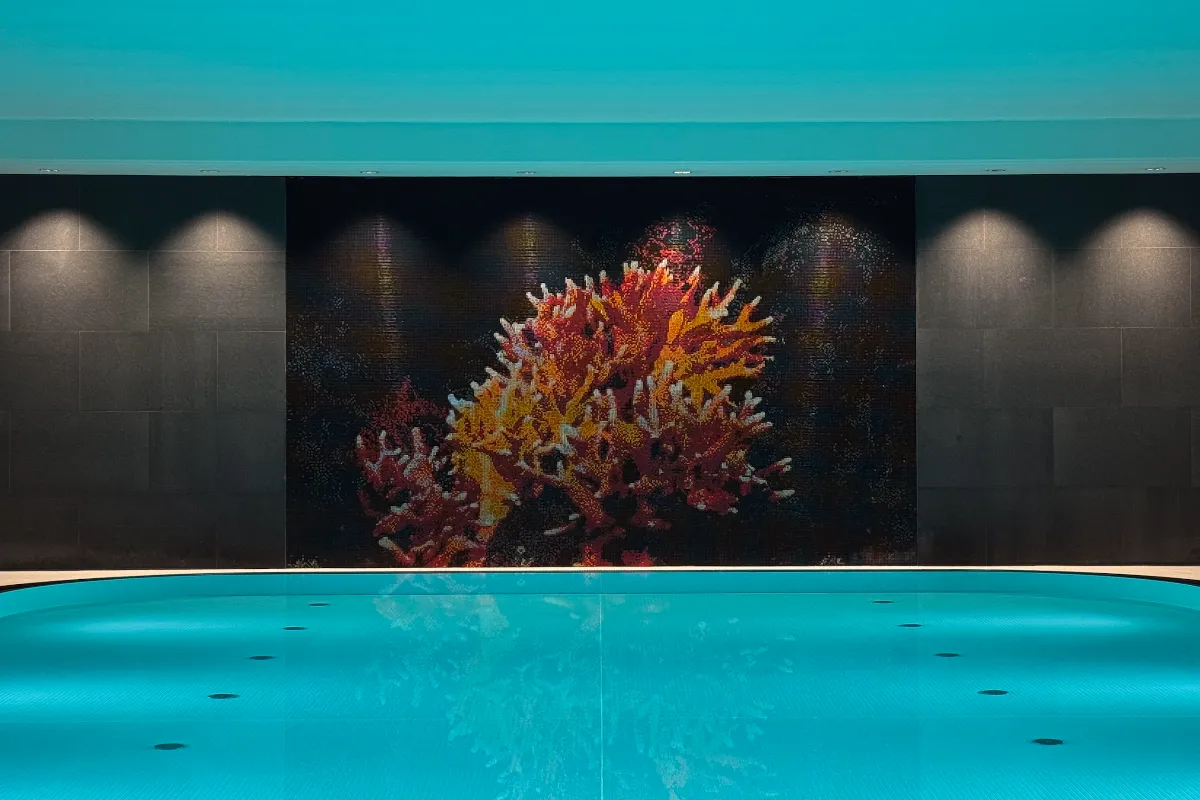

Located on the lower level, The Charles Spa is organized around a 15 × 8-metre indoor pool, gently illuminated and heated year-round. Designed by Lady Olga Polizzi, the spa translates the architectural vocabulary of the hotel into a coherent subterranean environment — calm, tactile, and warm.

Light limestone surfaces combine with pearlescent green-glass mosaics that line the pool and humid areas. The pool’s main wall features Bisazza mosaic stones depicting coral motifs in vivid red tones – an artistic allusion to the Bavarian noble family Wittelsbach, who used corals in their coat of arms.

Along the north side of the pool, three stone chaise longues, also clad in mosaic and internally heated, offer a sculptural complement to the space. Adjacent areas include a sauna, steam room, and footbath zone, all designed in the same restrained and natural language.

The Old Botanical Garden, Munich – landscape heritage and urban continuity

For The Charles Hotel, standing directly along the garden’s northern edge, the Alter Botanischer Garten is far more than a pleasant view — it is a design reference.

Covering roughly four hectares between Munich’s central station and Karlsplatz (Stachus), the garden forms a vital hinge between the historic core and Maxvorstadt. Designed by Friedrich Ludwig von Sckell between 1804 and 1812, it served for more than a century as Munich’s principal botanical garden. Its original layout, inspired by the principles of the English landscape garden, organized plant collections within a network of winding paths and open lawns structured by a strong central axis — a feature still legible today.

After the botanical collections were moved to Nymphenburg in 1914, the area was gradually converted into a public park. In 1937, the Neptune Fountain (Neptunbrunnen) was installed at the centre, and the entrances redefined with wrought-iron gates and portals. Among them, the neoclassical gate by Emanuel Joseph d’Herigoyen (1812) remains one of Munich’s most recognizable landmarks.

Despite numerous transformations over the 20th century, the park retains its irregular layout of open lawns, mature trees, and layered vistas — a rare example of a historic landscape surviving intact in the dense, infrastructured core of a European capital.

Matteo Mammoli