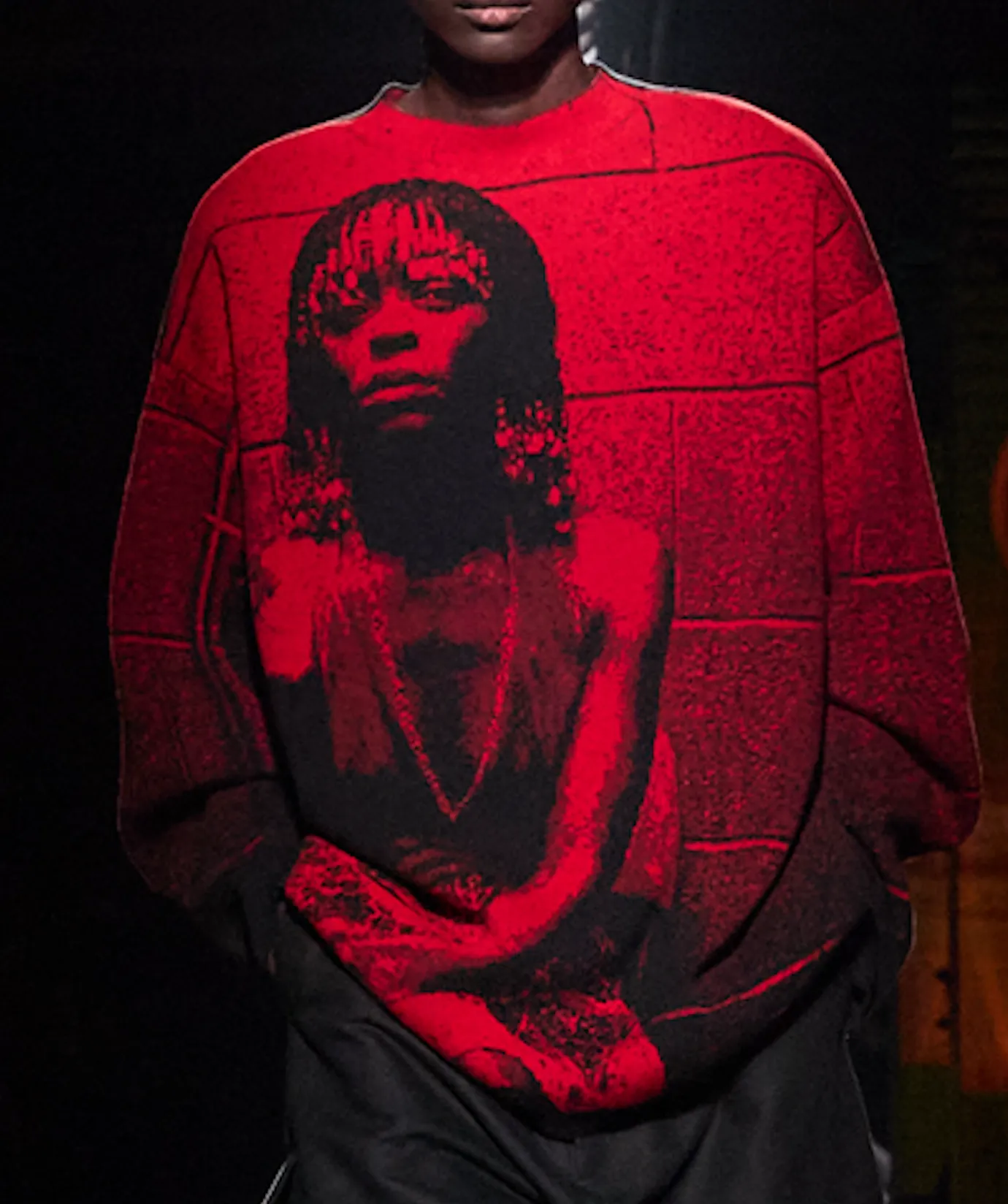

Adrien Dubost for Lampoon 32 – SOAP: Cartier in a bubble bath

Adrien Dubost takes the Maison’s jewelry out of the velvet box and straight into the sink. The pieces float through water, foam, fabric, blueberries, and a few accidents that look suspiciously like breakfast

Dubost turns the usual Cartier mise-en-scène upside down for Lampoon 32 SOAP

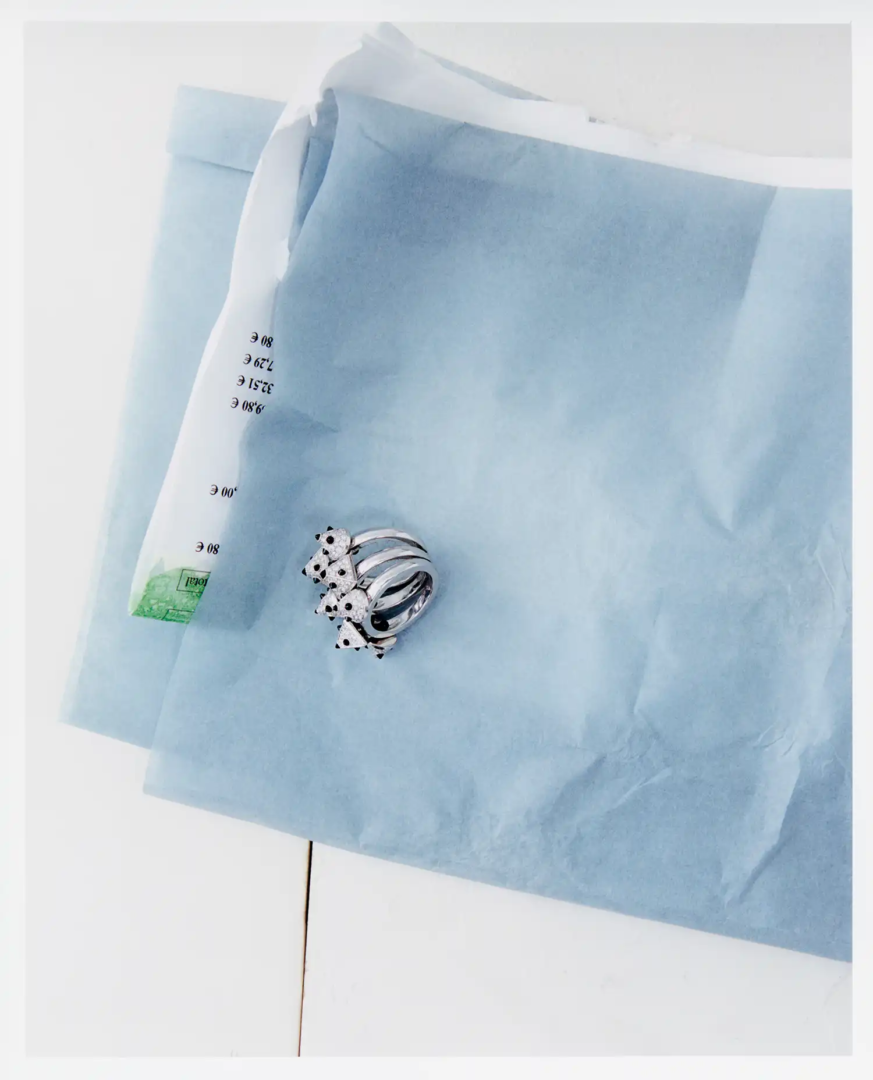

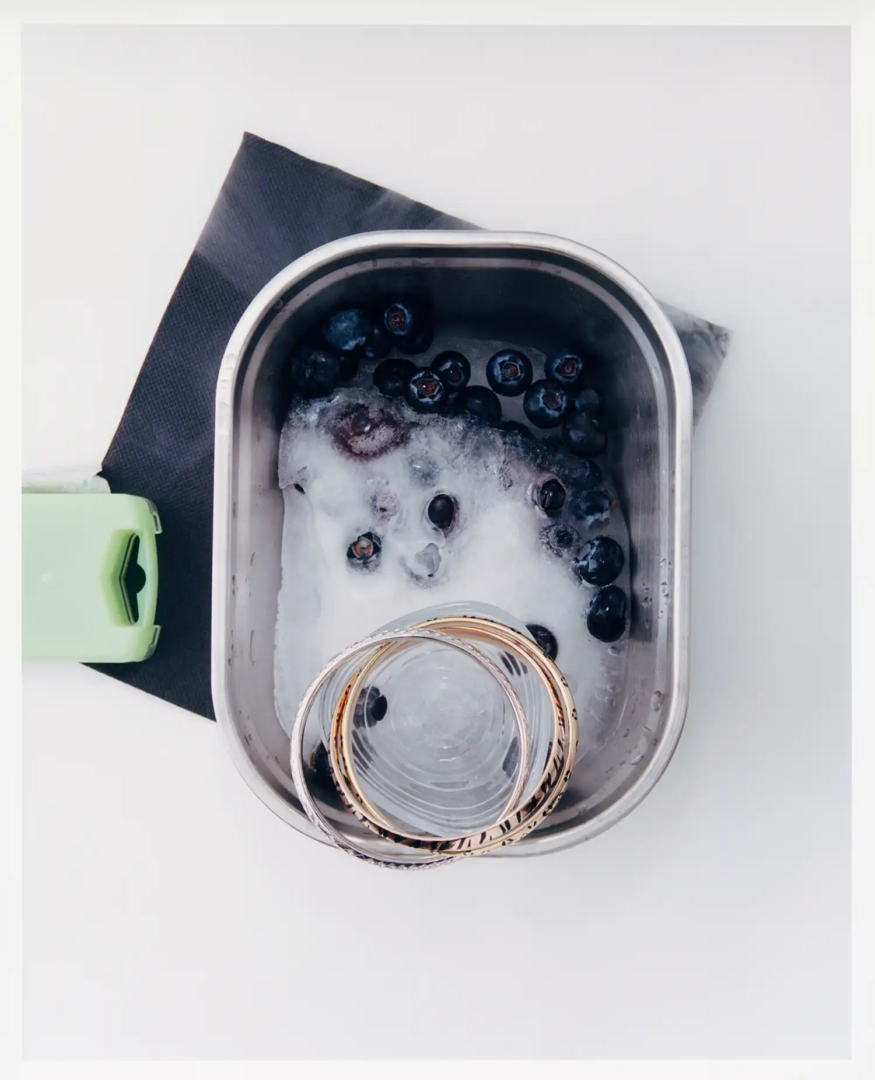

Cartier, but make it slippery. For Lampoon 32 – SOAP, photographer Adrien Dubost takes the Maison’s jewelry out of the velvet box and straight into the sink. The pieces float through water, foam, fabric, blueberries, and a few accidents that look suspiciously like breakfast. The result isn’t luxury as display — it’s luxury caught off guard. Rings and bracelets end up half-drowned, half-glowing, still holding their composure even when surrounded by soap bubbles.

Dubost turns the usual Cartier mise-en-scène upside down. The background is no longer marble or mirrored glass but a domestic mess — towels, bowls, stains, a soft blur of daylight. The images feel like evidence from a bathroom crime scene involving too much elegance. It’s a kind of visual joke about perfection: no diamonds were harmed, but none were spared from the suds either. Cartier stays Cartier, even under water pressure — clean, polished, and, somehow, funnier for it.

Cartier collections: six systems of form and meaning

Between Dubost’s playful compositions and Cartier’s internal logic lies a shared fascination with structure. The photographs in SOAP suspend the jewels in unstable, fluid environments — foam, cloth, water — where reflection and distortion expose how each piece reacts to contact and movement. The same principle, stripped of humor, defines Cartier’s own practice: a continuous study of how form holds under tension, how geometry resists or adapts. Moving from the domestic chaos of Dubost’s images to the ordered frameworks of the Maison’s collections is less a contrast than a translation — from improvisation to system, from gesture to method.

Across more than a century of production, Cartier has built a recognisable framework for design: a consistent use of structure, proportion, and material logic. Each collection operates as a case study in how an established house organises form and process. The six examined here — Clash [Un]limited, Trinity, Les Berlingots, Faune et Flore, Panthère, and Cartier Libre – TuttiTutti — outline the internal mechanisms of a brand that uses continuity as a method rather than a style. Together, they map a system where repetition, adaptation, and technical refinement function as the basis of identity.

Clash [Un]limited de Cartier: how engineering and modular design define a new Cartier language

Launched in 2022 as an evolution of the 2019 Clash de Cartier line, Clash [Un]limited focuses on the technical logic of movement within jewelry. The stud motif, inspired by Cartier’s early twentieth-century clou carré pattern, becomes a functional mechanism. Each stud is mounted on a micro-spring that allows limited motion without compromising stability. White gold, onyx, and diamonds are arranged in sequential grids, generating rhythm through repetition rather than decoration. The design process treats each element as a module, creating a structure that moves while maintaining order.

The collection demonstrates a shift toward architectural thinking inside Cartier’s design practice. Gender neutrality, mechanical precision, and visible structure replace traditional ornamentation. Clash [Un]limited uses repetition as an engineering method rather than an aesthetic effect, positioning movement as part of the jewel’s anatomy. It reflects how contemporary Cartier incorporates mechanical intelligence into the surface of its pieces, translating technical innovation into visual identity.

Trinity de Cartier: exploring continuity, proportion, and the geometry of three metals

Created in 1924 by Louis Cartier, Trinity is founded on the intersection of three circles. The yellow, rose, and white gold bands are linked but independent, sliding across one another without a visible joint. The system produces constant rotation and balance, relying on precise calculations of curvature and metal hardness. Over time, Cartier extended the concept into bracelets, necklaces, and earrings, adding enamel, lacquer, or diamond pavé while preserving the structural logic of three interdependent rings.

Trinity remains a central code in Cartier’s design language. Beyond symbolism, it serves as a technical exercise in proportion and tolerance. The exact calibration of each ring ensures mobility without deformation, making Trinity a continuous laboratory for testing materials and finishes. Its longevity lies in its simplicity as a mechanism — a self-contained structure that expresses Cartier’s capacity to merge mathematics, movement, and metallurgy into a single form.

Les Berlingots de Cartier: geometry, color, and the material study of volume

Introduced in 2019, Les Berlingots de Cartier belongs to the Maison’s ongoing exploration of color as structure. The collection takes its name from the triangular French candy “berlingot,” reinterpreted through precise geometry. Chalcedony, chrysoprase, carnelian, garnet, and malachite are cut as high cabochons and enclosed in rose or yellow gold settings. The focus is on solid volumes and uniform color, with metal functioning as containment rather than decoration. Each piece is built around the optical and tactile qualities of a single stone.

The collection studies color as a three-dimensional material rather than surface treatment. Cartier’s gemologists select stones for tonal consistency and texture, ensuring that the visual density of the piece is even across its structure. The result is a design language centered on matter and touch. Les Berlingots operates as a contemporary exercise in minimal construction, where light, density, and geometry define the identity of the jewel.

Faune et Flore de Cartier: translating natural forms into high jewelry structure

Faune et Flore de Cartier is part of Cartier’s high jewelry corpus and brings together pieces inspired by animal and botanical forms. Originating in the 1930s, the collection follows a consistent principle: transforming nature into a geometric and modular system. Emeralds, onyx, white and yellow diamonds, sapphires, and citrines are arranged to build texture and controlled movement. Each piece begins with a wax model, later rendered in gold or platinum, emphasizing construction over decoration.

The collection functions as both archive and laboratory. New interpretations appear regularly in high jewelry presentations, with recurring motifs of birds, felines, and flora. The focus lies in the technical translation of organic rhythm — the balance between solid and void. Faune et Flore reveals how Cartier abstracts nature into a language of engineering, transforming the observational into the structural and establishing a bridge between sculpture and ornament.

Panthère de Cartier: from symbolic animal to modular design identity

The panther first appeared in Cartier’s vocabulary in 1914, on a watch with onyx and diamond spots. In 1917, George Barbier’s Dame à la panthère illustration formalized the motif. By the 1930s, Jeanne Toussaint, Cartier’s creative director, established the panther as a recurring three-dimensional subject. In 1948 the first complete panther brooch was made for the Duchess of Windsor, setting the foundation for a continuing lineage. The form evolved into rings, pendants, and bracelets, often with flexible bodies and skeletal interiors.

During the 1980s, Panthère de Cartier expanded into watchmaking, giving its name to a square, soft-edged case and articulated bracelet. The construction demands complex stone setting, alternating onyx and diamonds to recreate the feline’s coat. Today, the panther functions as a modular emblem: sometimes literal, sometimes abstract, but always structural. It bridges Cartier’s figurative and geometric traditions, representing continuity through variation and the persistence of a single design archetype.

Cartier Libre – TuttiTutti: experimental geometry and color research within Cartier’s creative system

Cartier Libre began in 2017 as an internal research project for limited-edition pieces that reinterpret the Maison’s historic codes. The 2023 TuttiTutti series combines yellow and white gold with chrysoprase, onyx, and diamonds. Each jewel is composed of asymmetrical modules, diagonal cuts, and non-traditional chromatic contrasts. The construction allows elements to rotate or invert, creating multiple configurations. Production is limited, often to unique pieces.

The project serves as a platform for testing new assembly and hybrid stone-setting methods. TuttiTutti investigates how rhythm and color operate as structural principles rather than visual effects. The series functions as an experimental workshop inside Cartier’s ecosystem, where research on thickness, tension, and surface informs future collections. Cartier Libre represents the Maison’s capacity to analyze its own design grammar, translating experimentation into process rather than trend.