Amanda Ba, For Sports: Finding Culture in Athleticism

The rawness is being willing to take an L and take a risk and change something. Maybe it’ll make you less popular than you were before, but you’re trying something new. Interview with Amanda Ba

Amanda Ba’s Late-Night Painting Sessions and Upcoming Micki Meng Exhibition in San Francisco

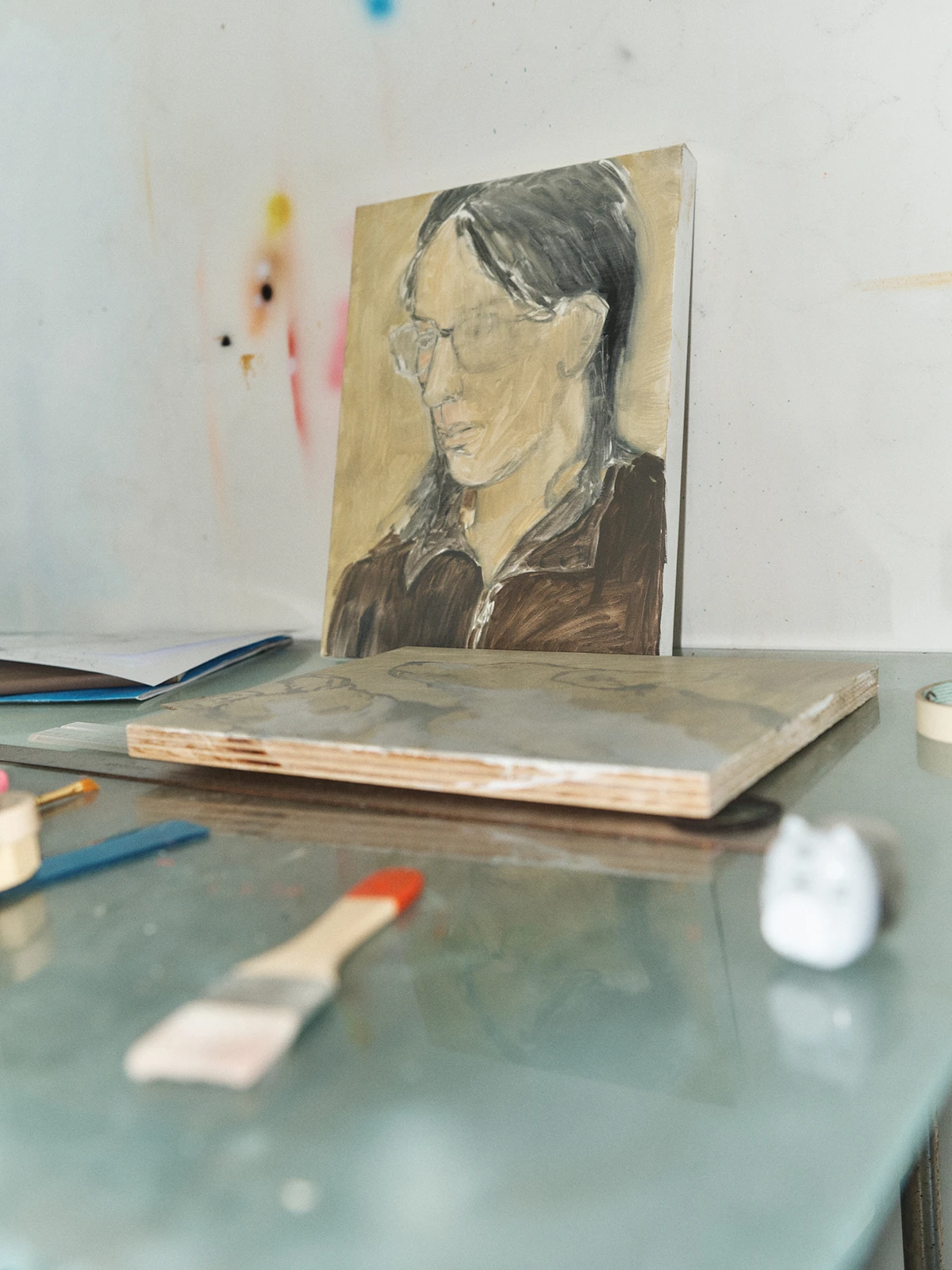

It’s midnight in New York. Fresh from dinner, Amanda Ba is settling into her studio for another night session—preparing for her upcoming show at Micki Meng in San Francisco in late May.

Behind her, a new painting is taking shape: a warm dusk-yellow glow suffuses the canvas; the ghostly outlines of hunting beagles are yet to be rendered; a rocky landscape is emerging beneath a trench-coated figure in motion. The scene is both a continuation and a departure from Ba’s vocabulary. It references the bleak, Andrew Wyeth-inspired landscapes and recurring dog motifs that have become commonplace in her work—but ventures into a new arena: athleticism.

“Developing Desire”: Amanda Ba’s Jeffrey Deitch Gallery Debut on Urban China, Economies of Longing, and Monumental Female Titans

Last September, the American-Chinese artist marked her New York solo debut with _Developing Desire_, an exhibition that transformed Jeffrey Deitch Gallery into an exploration of economies of desire and urban development in contemporary China.

Canvases depicted nude female titans commanding crumbling urban spaces—towering over Shanghai’s skyline and the unabating interchanges of Huangpu’s highways. A sixteen-panel billboard presented portraits of women in different professions, tiled together like a Zoom call; its reverse was covered in collaborative drawings referencing revolution-era dazibao protest posters. A three-channel video, created with her partner Justine Cheng, wove together staged and documentary footage of life in Hefei, the city where Ba spent her early years.

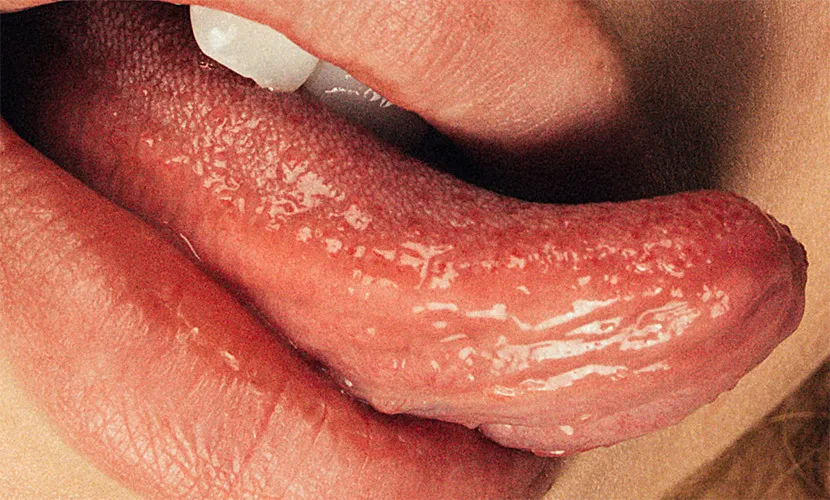

Blood-Red _Love Lies Bleeding_ Vinyl Art: Amanda Ba’s A24 Collaboration Captures Erotic Tension and Physical Power

In May of last year, her blood-red artwork for the _Love Lies Bleeding_ vinyl—bulging, bikini-clad bodies locked in a scissor hold—proved a perfect match for the A24 film’s steroid-fueled world of erotic tension and physical power.

Defying a Signature Style: Why Amanda Ba Embraces Creative Risk and “Taking an L” to Keep the Work Fresh

Yet Ba continues to resist settling into any single signature style, deliberately challenging audience expectations with each new body of work. It’s an approach she acknowledges might alienate collectors who prefer consistency, but Ba remains committed to following her curiosity wherever it leads—even if that means taking an L.

Art, Sports, and Global Identity: Amanda Ba on Olympics Inspiration, Pakistan’s Weight-Lifting Hero, and National Pride

Amanda Ba: Art and sports are often far apart culturally, and the types of people interested in each tend to be different. I’m fascinated with sport as a dedication to physicality. When I look at competitions like the Olympics or any international championship, individual people’s athleticism can translate to the pride or nationalism of an entire country.

In recent Olympics it’s always been China and America competing for medal count. When you have a weight-lifter from Pakistan—who had very little professional training compared to others—winning a gold medal, that becomes a big deal for everyone in Pakistan. It reflects what’s happening globally and it gives people an identity. You know, like how being from a certain state in the Midwest ties you to a football team, and being from a city in England ties you to a soccer team.

I was tired from my last show. It was my debut solo in New York and the space was huge—conceptually and formally rigorous—and I put a ton of work into it. It was all guns firing for seven or eight months straight. I wouldn’t say I was burnt-out—that’s a low point, and you know when you’re burnt-out—but it was intense. With this upcoming show, the space is smaller, so the scale is also smaller. I’m trying to have fun and experiment more with painting itself. Conceptually, I still need something to latch onto. It’s going to be called _For Sport_, and it’s all about athleticism and what the implications of athleticism can be politically, nationally and globally.

I have cinematic dreams—different camera angles, CGI, shifting narratives. For a period I made a point of voice-recording my dreams: I’d wake up and describe what happened. That trained my mind to remember them more vividly. When I approach my paintings, it’s logical; I’m piecing together things that make sense together. Dreams are nonsensical. My dream life is separate from my reality, and my paintings can sometimes be quite serious about reality, even if they’re funny or light-hearted.

From Lucian Freud to Red Dogs: Copying Masters, Finding Voice, and Painting the First “Me” Canvas at Slade in 2019

HS: There’s this idea that you must copy before you can create. Lucian Freud was an early reference point for you.

AB: When you’re learning something you can only copy—everything you’re doing is mimesis. You find out what you like and then you try to make something like that. What you end up making is something between what you make and what that person you’re trying to copy makes. Early in college I was just making Lucian Freud paintings, Alice Neel paintings, David Hockney paintings, Alex Katz paintings.

HS: What was the first painting you made that felt like you?

AB: It was a dog painting I made at Slade in 2019: a woman lying down with four red dogs surrounding her. The dogs are about to attack her but she’s unaware—she’s in a fugue state. Is she aware of the dogs’ presence? Is that a layer of subconscious interpretation—are we seeing what she thinks she’s seeing? Even though that painting wasn’t fully developed into my style, it set the tone for many of my first successful works, when I was in my “red period”. That painting wasn’t all red; it was just the dogs. After that I made a whole series whose primary colour was red, and there were dogs in all of them.

Post-Human Theory, Topic Switching, and the Martin Kippenberger Model of Varied Artistic Practice

I learned that I needed to dissect my interest in dogs. I read a lot of post-human theory about our hierarchical relationship to animals and other living and non-living things. Then I realised I like to work this way—it’s productive. As I switched topics, the look of the work changed. At Slade I realised you don’t have to do anything—your time is your time. I had a lot of free hours to make work and to go look at art.

I feel vulnerable about the whiplash of switching topics and styles with every show. I’m not giving myself—or the audience—a moment to breathe. There’s a sweet spot where people want to see work they like and keep seeing it for a while. It’s like when an artist drops an album you love: you want one or two more in that vein, and then if they keep repeating it you’re like, “Okay, time to switch.”

It’s like what happened with Beyoncé’s _Cowboy Carter_, the album that won the Grammys. It’s different from what we expected. Everyone’s like, “Who’s listening to this?” I’m not really listening to it, but I recognise it as a rigorous exploration of country music. Half of America listens to it and the other half… not so much. It’s also politically charged.

If you’re good enough at being a jack-of-all-trades and you sustain that long enough, it becomes your style. Martin Kippenberger could do everything. You look at one year of his work and think, “What the fuck, this is all over the place!”—but he kept it up long enough that you’re like, “Wow, he has an extremely varied practice.”

Beyoncé, Magnum-Opus Anxiety, and the Value of Raw Experimentation in Contemporary Painting

HS: Not everything has to be your magnum opus, and some people’s best work isn’t their most commercially successful.

AB: The rawness is being willing to take an L—to risk, to change. Maybe it’ll make you less popular than before, but you’re trying something new. I get bored, maybe faster than the public gets bored.

Building a Visual Vocabulary: Olympic Slow-Motion Replays, 360-Degree Cameras, and 100-Image Reference Folders

HS: When you’re moving into new territory, how do you build your vocabulary? Some artists avoid references altogether. Is your process more visual or theoretical?

AB: Primarily visual. The idea started visually—watching the Olympics every couple of years. I’m binging YouTube clips of women’s 100-metre dashes and the visuals they use to keep time. They have these crazy 360-degree cameras that capture every bit of action as you cross the finish line.

For every painting I start, I have a folder with 50–100 images. Each of these dogs (gesturing behind her) has at least one, maybe three references. I draw individual dogs from several images, drop them into Photoshop, compose, tweak. There are so many moving parts that I don’t want all their faces obscured—I need the scale right. Painting purely from imagination is hard; if I ask you to draw a bicycle you’ll pause and wonder what a bicycle actually looks like.

My last show was reading-heavy—I leaned on theory to keep the topic tight. Whenever you’re dealing with politics or theory you need to get it right; whole careers are devoted to those subjects.

Beyond Shock Value: Porn-Site Taxonomies, Transgression Fatigue, and Deeper Artistic Questions

HS: You’ve said you felt lost once the shock factor of female Asian nudes wore off and the work didn’t feel transgressive anymore. Do you need to be transgressive?

AB: I’m drawn to transgressive things. There’s an initial shock, but I’m more interested in what’s underneath. It’s like the front page of a porn site—once you stop staring at the graphic header you start asking, Why are the categories organised like this? Who coded this? Are they ranked by algorithmic popularity? The surface shock isn’t shocking anymore, so the interesting part is why it exists and why we’re still attracted to it.

Dressing the Athlete: Sport Fashion, Arc’teryx Elitism, and Hyper-Contemporary Context in the “For Sport” Series

HS: The presence—or absence—of clothing in your work feels intentional.

AB: I leave figures nude when I want them to feel eternal or blank. In this sport series none of my figures are nude, which is telling—I’m pin-pointing a specific time, place, context. Dressing them lets me push that context further.

There’s a cult-like dress culture behind every sport. People get amped to assemble their ski outfits—you need Arc’teryx, you need Oakley. Sport-specific brands become a prerequisite for the “look” even before you’re good enough at the sport for skill to matter.

HS: There’s an elitism there, too.

AB: Absolutely—that’s part of how I’m dressing the figures. It’s hyper-contemporary.

Financial Independence as Artistic Freedom: Cutting Parental Support and Thriving in the U.S. Art Market

HS: This issue explores the theme of independence.

AB: The first thing is financial independence. I’m in America, the nation of “independence”, but that’s too broad, too empty. Financial independence gave me the actual freedom to pursue art. With my parents it wasn’t worth chasing their empathy—“we understand why you’re doing this.”

Near the end of college I stopped taking money from them. I hustled until I could earn enough doing what I loved. My attitude was, *If you don’t like it, I’ll show you other people do—they’ll spend bags on it.* Once that happened my parents backed off and my confidence shot up.

Generative Fill, Upscalers, and Outsmarting Algorithms: Amanda Ba’s Pragmatic Approach to AI in Fine Art Practice

HS: What’s your relationship to AI?

AB: A helpful, sometimes stupid tool. I use Photoshop’s generative-fill. I use AI up-scalers when the perfect reference image is 500 × 800 px and looks like shit—I pay ten bucks to get a 5 000-pixel version.

It’s annoying when I search for references: I type “beagle hunt” and 80 % of the results are AI beagles, fake paintings in faux-European classicism. In thumbnail they look like Met paintings; you open them and go, “Oh, this is garbage.”

You have to out-smart the tool. If it speeds up your drafting, you need to be smarter with what you do next. We’ll see if the desire for original thought outweighs the urge to do something easy.

Social Media Serendipity: Instagram Leads to A24 Collaboration and 95 Percent of Career Opportunities

HS: Adults can choose how to use these tools, but it’s different for kids. Outsourcing menial tasks might affect cognitive development. Teachers have to grapple with capabilities they don’t yet understand.

AB: Boomers feared social media would wreck millennials’ ability to socialise—didn’t happen. We’re still social; individuality won out. Yes, people get addicted, but we work with it.

Pessimistically, AI might smooth-brain some teens; optimistically they’ll use ChatGPT to plan a trip to Thailand and experience more than their boomer parents ever could.

HS: Roughly 90–95 % of your opportunities have come through social media. Was that true for the _Love Lies Bleeding_ vinyl?

AB: Somebody from A24 emailed me, but I’m sure they found me on Instagram—how else does anyone find anything now? I watched a screener before release. Honestly, I couldn’t tell you if the movie was good or bad—I was busy thinking about the images; I missed the plot.

Painting Archetypes over Celebrities: Avoiding Kristen Stewart’s Face and Focusing on Mood for the Love Lies Bleeding Cover

HS: The imagery makes a lot of sense with your work. How did you approach the piece?

AB: I didn’t want to paint either of their total faces because Kristen Stewart means too much to me personally for me to just straight-up paint her face. It felt like caving to my own fandom. The film runs on archetypes, not hyper-specific character studies: the middle-lower-class Mid-West girl who’s stuck; the runaway muscle lesbian; the abusive husband; the evil criminal father. I focused on tone, not likeness. We settled on partial faces; the bodies aren’t anatomically accurate either, but it captures the tone.

Recent Film Binge: Arrival, Molly’s Game, and Rediscovering the Harry Potter Series for Visual Inspiration

HS: What was the last movie you saw that moved you?

AB: I’ve kind of been watching stupid movies. I watched _Arrival_, that alien movie with Amy Adams—that was good. Then _Molly’s Game_, about the Hollywood poker ring (based on Tobey Maguire’s gambling issues). And I re-watched _Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince_. I’m re-watching the _Potter_ films and thinking, “Oh wow, they’re actually pretty good.”

Harriet Shepherd