Why is linen a noble fiber? A short or global supply chain: from Normandy to Italy

From the Terre de Lin cooperative to the manufacturing of the Albini Group: European linen and its traceability, between crop rotation, varietal selection and industrial weaving

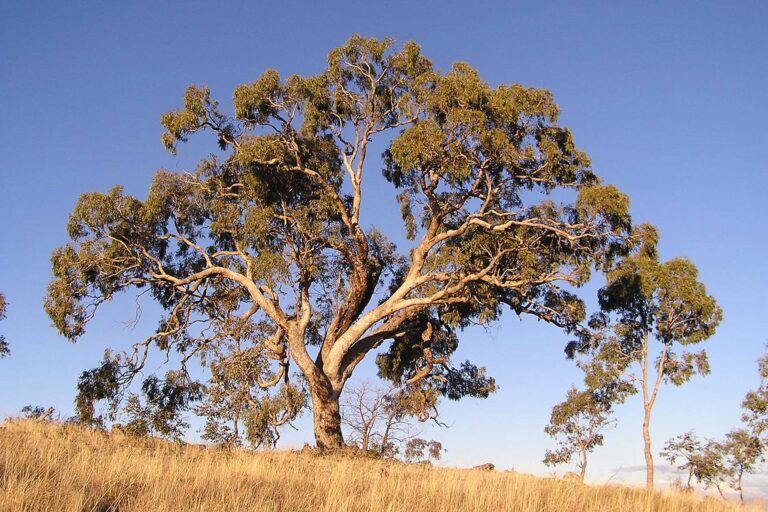

Linen in Normandy with Terre de Lin: a centuries-old cultivation that follows the rhythm of the land

In Normandy, Terre de Lin is the largest flax cooperative in Europe, made up of around 750 farmers and with more than twenty thousand hectares dedicated to flax production: “I’m the fifth generation. We grow flax every six years. I could do more, but I prefer this way: flax is a plant with memory.”

The crop is sensitive to how often it is sown on the same plot of land. Respecting a rotation of one in every six years reduces the need for fertilizers and produces longer, stronger fibers: “Flax grown with this care requires less nitrogen and maintains a higher retted fiber yield.” The retted fiber (filasse) is a long, high-quality fiber used for fine yarns.

Each phase of cultivation is planned in advance. The soil is kept in good condition through light work to preserve its structure and drainage capacity.

Ethical entrepreneurship: the shared story of Terre de Lin and Albini Group

Terre de Lin was founded in 1939, when local flax growers formed a cooperative to collectively enhance the value of their production. At the time, most of the fiber was sold to Belgian buyers. Today, the cooperative has six production sites and employs 400 people. It oversees every stage: from seed selection to the combing of long fiber, including retting, scutching, and classification.

The cooperative also creates and registers new flax varieties through breeding and crossing. It develops new cultivars tailored to specific climates or resistant to disease and pests. Terre de Lin sells these to third parties, including competitors, and holds the intellectual property rights to the registered varieties. Seed production gives members greater autonomy and resilience in the face of climate variability.

Terre de Lin collaborates with the Italian Albini Group, which sources its flax fiber from Normandy for fabric production. Founded in 1876 in Bergamo, where it still has its headquarters, Albini will celebrate 150 years of history in 2026. The company produces over 13,000 fabric references per year, exporting to more than 80 countries.

The collaboration between Albini and Terre de Lin began in the early 2000s. “Albini came to award our best farmers,” explains Anne Nizery of the cooperative. “It’s a long-standing relationship built on continuous dialogue.”

Natural raw materials: the flax cycle begins well before sowing – from field selection to natural retting

Flax cultivation follows a precise timeline. Field selection takes place three years in advance. After the wheat harvest, in the summer before sowing, stubble is cleared and the soil is lightly worked to avoid compaction: “We sow from March 15 onward, when the soil is dry and moisture is around eighteen percent.”

Flax has a growing cycle of about 100 days. It develops quickly and doesn’t tolerate obstructions, so the soil must be well-aerated, clod-free, and not compacted by unnecessary mechanical passage. Sowing is dense and shallow: up to 2,000 seedlings per square meter.

After flowering, seed capsules form quickly. The plant grows to 90–100 cm and is pulled from the ground, not cut, to preserve fiber length: “You have to strike the right balance between fiber development and seed formation.”

The flax is then laid in the field for natural retting, a process that lasts several weeks and depends on the balance of sun and rain: “The weather is in charge. The time window for action is short and must be constantly monitored.”

Circular economy applied to flax: scutching and fiber processing

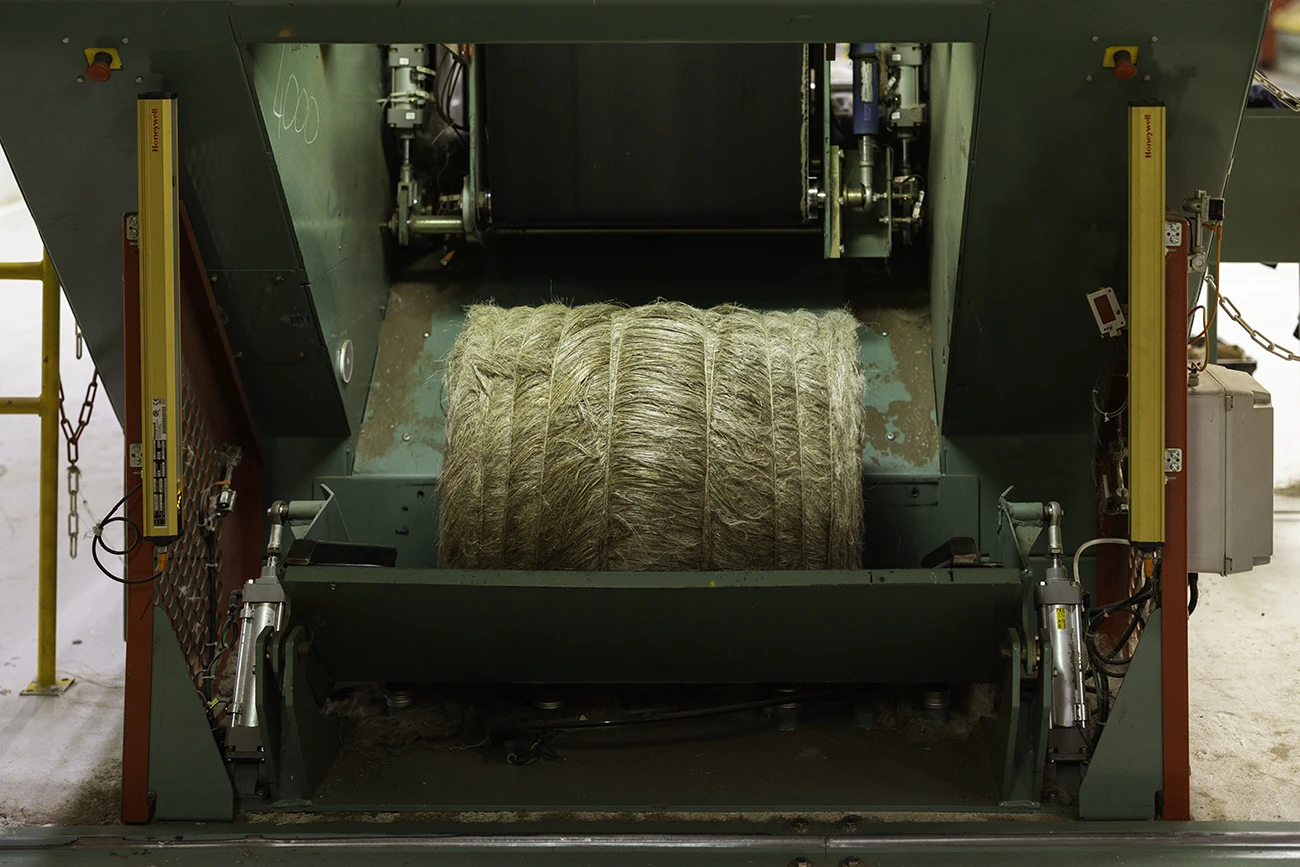

The fiber from the retting process is brought to Terre de Lin’s facilities for scutching. This step separates the woody core of the stem from the actual fiber. It includes several stages: scutching, combing, and classification.

Nothing is wasted. The woody byproduct is used for animal bedding, insulation panels, or biomass. Even the dust from scutching is recovered and used in agriculture as fertilizer: “We valorize every part of the plant, with a circular approach.”

Next comes fine combing of the long fiber, done with metal needles in humid conditions to avoid damage. The fiber is aligned, cleaned of impurities, and polished. Data is collected at every step: length, tensile strength, fineness. Classification is based on six criteria and also determines farmers’ remuneration.

Each batch is tested using resistance and fineness tools developed with industrial clients, including Albini. This creates a database used to regulate payments and assess each batch’s suitability for various industrial applications.

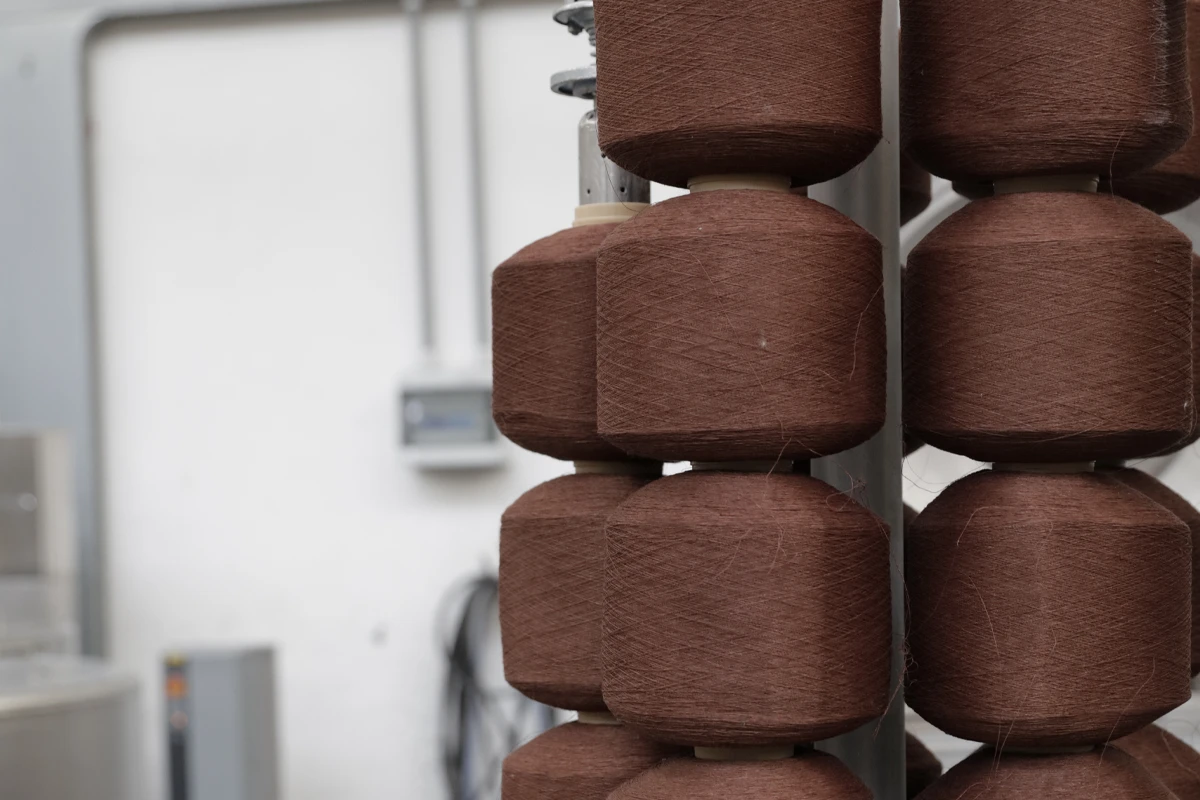

Flax spinning and dyeing. From fiber to fabric: thermoregulating, antibacterial, biodegradable

Spinning is the technical core of transformation: the fiber is first lubricated with vegetable oils to facilitate processing, then combed, stretched, spun, and finally twisted. The result is a continuous, even yarn, ready for dyeing and weaving.

Dyeing takes place in autoclaves, with strict controls on colorfastness, uniformity, and strength. The yarns are then woven on looms to create various structures: poplin for formal shirts, twill, or zephyr for lighter fabrics. Finally, finishing gives the fabric its desired hand and texture.

Ethical entrepreneurship: a certified and traceable flax supply chain

The relationship between Terre de Lin and its farmers is based on one principle: quality and yield determine compensation. Each batch is classified and paid based on objective criteria: “It’s a transparent system designed to reward those who grow best.”

Albini, in turn, controls every stage of the supply chain, from field to fabric. Traceability is ensured through internal monitoring and third-party certification. Suppliers are also assessed by country risk, with regular audits in more vulnerable contexts.

Albini Next: ecodesign and applied sustainability in the textile industry

Terre de Lin has a unit dedicated to research and experimentation: twenty hectares for varietal selection and agronomic trials. Seeds are disinfected with steam, without chemicals, and natural extracts like garlic are tested as pest deterrents.

The cooperative is also developing alternative agronomic solutions to adapt to increasing climate instability. Trials include disease-tolerant or early-growth flax varieties.

Meanwhile, Albini’s innovation hub, Albini Next, develops ecodesign and sustainability projects. Alongside Biofusion regenerative cotton cultivation, it continuously monitors its environmental impact. In 2023, it reduced water withdrawal by 36%, energy consumption by 29%, waste production by 31%, and landfill waste by 75%.

Albini and Terre de Lin aim to combine resilient agricultural practices with a fully traceable industry to generate shared value. Every fiber tells a story—of soil, labor, and ingenuity. From field to fabric, flax retains memory, form, and function.