Minimalism with a backbone: Gion A. Caminada carves Hotel Maistra 160 into Pontresina

Not another chalet and not Belle Époque cosplay, but a heavy, precise monolith of gneiss, terrazzo and Swiss stone pine that turns a central Pontresina plot into a sanctuary of grounded design and alpine stillness

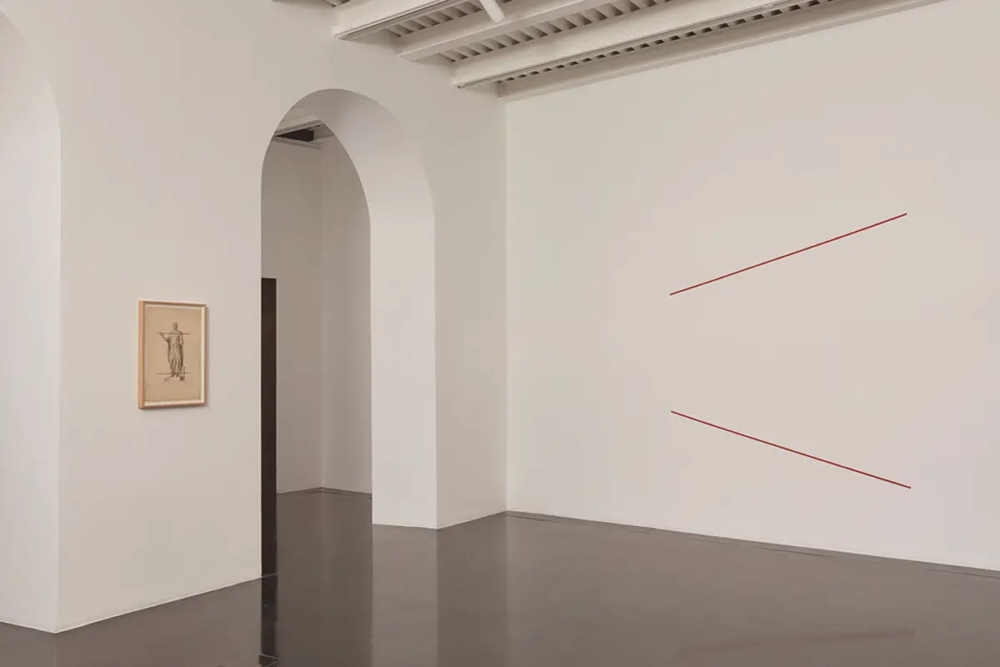

Minimalist design in the Engadin: Gion A. Caminada’s sanctuary for Hotel Maistra 160 in Pontresina

Hotel Maistra 160 takes its name from its exact street address on Via Maistra, the central spine of Pontresina. The choice is almost provocatively modest: no invented brand, no poetic suffix, just a geographic coordinate. It sets the tone for everything that follows. Where the historic Hotel Post once stood, a new monolithic volume—completed in 2023 after several years of demolition and reconstruction—now rises in its place. Conceived by Grisons architect Gion A. Caminada and developed by hoteliers Bettina and Richard Plattner, the 4-star superior hotel reframes Engadin hospitality as an exercise in material honesty and quiet precision.

The property houses 36 guestrooms and 11 lodges, along with a restaurant, bar, curated library, event spaces and a two-level spa built around an open-air courtyard. Rather than echoing Pontresina’s Belle Époque façades or the chalet vernacular common to the Upper Engadin, Caminada pursues something far more radical: a structure that feels carved from the mountain itself, a block of stone and concrete tuned to the altitude, the light and the long winters of the valley. The address, the architecture, the atmosphere—everything gravitates toward understatement. This is not a hotel that shouts its presence; it resonates.

Maistra 160, Pontresina: a statement of place, not a marketing gesture

Pontresina’s visual language is steeped in ornament. Painted facades, decorated sgraffiti, carved balconies—hotels often wear their history on their exterior. Maistra 160 does the opposite. Its name is literal, almost administrative; its façade is disciplined, gridded, composed of deep loggias and vertical fins of local stone. The effect is both contrasting and anchoring: the building breaks with the decorative tradition while remaining unmistakably tied to its site.

Replacing the former Post Hotel required a near-complete erasure of the previous structure. Yet the new volume is not an attempt to overwrite the past. It acknowledges the continuity of the plot, the rhythm of arrivals, the flow of Via Maistra. Naming the building after its address reinforces this: it is neither concept nor fiction, but simply the truth of where it stands. In a valley just seven kilometres from St. Moritz—where luxury often leans toward spectacle—this refusal of embellishment reads almost like a manifesto.

A new Engadin archetype: Caminada’s minimalism of mass, proportion and quiet luxury

Caminada’s work is rarely about formal bravado; instead, it listens to place. For Maistra 160, he distills the Engadin into a set of architectural principles: the dignity of understatement, the gravity of stone, the clarity of light, the slow cadence of mountain life.

The exterior is rigorous and compact. Inside, the building opens into a choreography of materials and volumes. Public areas are defined by high ceilings, stone columns, a continuous terrazzo floor and a chromatic palette derived directly from the surrounding Bernina massif. Rooms and lodges soften the tone through timber: walls, floors and ceilings wrapped in Swiss stone pine, a species deeply rooted in the region’s domestic architecture.

Each guestroom includes a Stüvetta, a miniature retreat within the room—part reading nook, part hideaway cabin—enclosed entirely in pine. Above the beds, softly lit ceilings carry hand-applied floral motifs, reinterpretations of historic Engadin ceiling paintings. These touches complicate the minimalism: they introduce quiet narrative moments, lingering traces of local tradition re-coded for the present.

Maistra 160 becomes, in this way, a study in silent luxury: a space where emotional warmth arrives through texture and scent rather than decoration, and where minimalism is not an aesthetic austerity but a form of generosity.

Stone, terrazzo, jade and Urushi: material storytelling as the DNA of Maistra 160

The hotel’s material palette is unusually coherent. Caminada builds from a triad of stone, concrete and wood, but the specifics are what give the project its voice.

The façade and many structural elements are clad in Bodio Nero gneiss, a dark grey stone quarried in Ticino. Used as vertical pilasters and deep façade elements, it anchors the building visually to the surrounding geology. Inside, the mineral story continues: floors in hand-poured terrazzo—a process that unfolded over several months—embed fragments of jade from Valposchiavo, creating minute green sparks in an otherwise quiet surface.

Colour expert Lucrezia Zanetti developed the interior palette by grinding local rocks into pigment, letting the Engadin’s geology determine the hues of the walls. The effect is subliminal but powerful: the interior feels like a chromatic echo of the landscape.

Timber appears where intimacy matters. The extensive use of arven (Swiss stone pine) introduces softness and a delicate fragrance, particularly in the guestrooms. Beside these alpine materials, the designers introduce unexpected notes such as Urushi lacquer, applied in thin, tactile layers to select tables and surfaces. The Japanese technique adds depth and gloss at a level that avoids ostentation; it feels more like a whisper than a signature.

Furnishings eschew hotel catalogues in favour of curated, residential-quality pieces: Seal lounge chairs by Audo CPH, design icons from Molteni&C, Fritz Hansen and Cassina, and sculptural lighting by Lee Broom. Custom-made joinery and stonework complete an interior that feels lived-in, not staged.

The Plattners behind Maistra 160: a 35-million project and a hospitality culture built on people

Maistra 160 is the most personal project to date for Bettina and Richard Plattner, a couple with deep roots in the Engadin’s hotel world. After decades managing and developing properties in Pontresina and Zuoz, they founded their own company, shaping a portfolio that blends design-driven apartments with contemporary Alpine hospitality. The new hotel required an investment of approximately 35 million Swiss francs—a figure that places it closer to cultural infrastructure than to a conventional hotel business model.

Their management philosophy prioritises a people-first culture. The hotel is run by an experienced director couple and a team described as collaborative, international and long-settled in the valley. Guests consistently read the atmosphere not as formal or ceremonious, but as quietly attentive—the kind of service that feels natural rather than choreographed.

Maistra 160 attracts an equally distinct clientele: travellers with a cultivated sensibility, architecture enthusiasts, readers who disappear into the library for hours, remote workers who treat the lodges as alpine studios, and mountain lovers who divide their days between slopes and spa. Luxury here is not about opulence but about calm, literacy and presence.

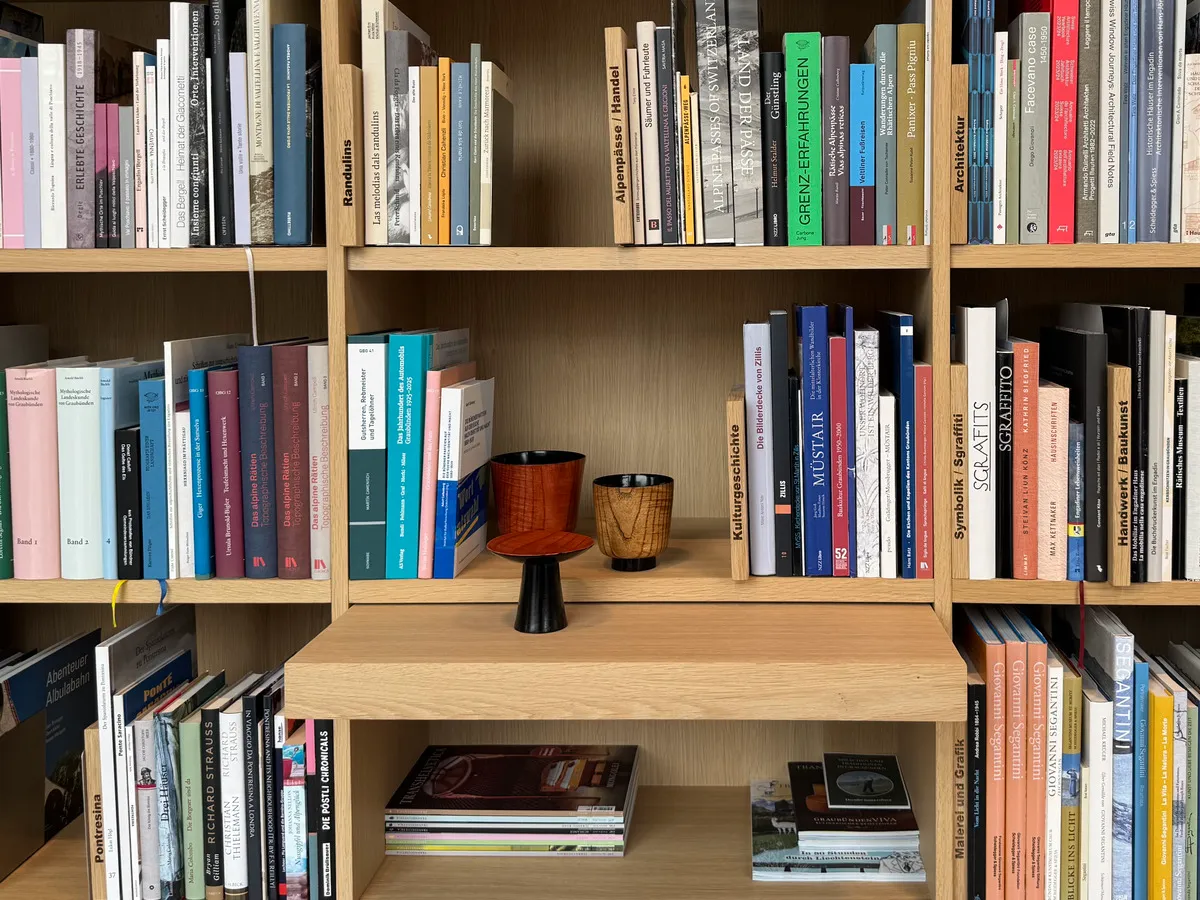

The library: the intellectual core of Maistra 160

Books have a permanent place at Maistra 160. The hotel boasts a carefully curated library, home to around 1,000 titles — a mix of literature, alpine history, art, culture of the Engadin and surrounding regions, regional novels, women’s writing from Graubünden, texts on mountain agriculture, hotel-industry history, monastic life, emigration stories, alpine cuisine and much more. The selection offers guests a chance to dive into the many facets of the high valley and its cultural layers.

This is not a decorative add-on: the library hosts book presentations and readings, and the curated selection is regularly refreshed. Guests can even borrow books via a “book trolley,” or purchase selected works at the hotel’s Concept Store — turning reading into an integral part of the Maistra stay.

Sustainability through design and behaviour: energy, water, textiles and the refusal of waste

Sustainability at Maistra 160 is built as a system of behaviours rather than slogans. The building employs high-performance insulation, solar panels on the roof, and a compact volume designed to minimise energy loss. Materials are predominantly local—stone, pine, terrazzo aggregates—reducing transport impact and ensuring longevity.

In the spa, water management becomes almost architectural. The outdoor relaxation pool is treated as a heat reservoir: covered at night, it retains warmth so that morning reheating consumes significantly less energy. The gesture is simple, invisible to the guest, but emblematic of the hotel’s method: efficiency without spectacle.

In the rooms, sustainability manifests as absence. There are no single-use plastic bottles and no minibars. Instead, each floor includes a communal kitchenette with equipment for tea and coffee and taps delivering filtered boiling, chilled and sparkling water. It is less about deprivation than about rethinking convenience as a shared resource.

Even the textiles carry a human scale: tablecloths hand-sewn, linens chosen for durability and tactile quality. Everything suggests a refusal of the disposable in favour of the lasting.

The spa as the hotel’s energetic core: a cloister to the sky, a future-like calm and a stone that speaks of origin

The MAISTRA Spa deserves its own chapter. It is conceived as the energetic centre of the hotel—a contemporary cloister organised around a square courtyard open to the sky. Weather enters the architecture directly: in winter, snowflakes drift into the void; in summer, sunlight cuts brief, concentrated lines onto the stone.

The journey through the spa alternates between compression and release. Narrow corridors in dark gneiss open suddenly into a double-height atrium lined in warm pink marble, with a fire at its core. From there, doors lead to saunas, lounges and treatment rooms, all stripped of decorative excess. The impression is cinematic, almost futuristic: a vision of a civilisation that has learned to merge nature, stone and minimalism with an advanced sense of calm.

At the centre of the courtyard, a sculptural stone presence rises like a geological marker—an object that feels both ancient and intentional, reminding visitors of origins and trajectories.

The steam room, lined entirely in deep basalt, amplifies the elemental tone. Basalt, a volcanic rock capable of withstanding extreme temperatures, creates a primal, cavernous environment. Inside, at 42 degrees and full humidity, the room feels less like a spa chamber and more like a remnant of cooled magma adapted for human ritual.

Everywhere, the spa insists on reduction. It removes noise—visual, acoustic, psychic—until only stone, water, air and body remain.

Short supply chains and mountain terroir: how the kitchen extends the hotel’s design philosophy

The restaurant reinforces the architectural language: granite columns, a terrazzo floor with Bernina stone, a textile coffered ceiling that softens acoustics, and dark walnut furniture that recalls a modern alpine apartment rather than a hotel dining hall.

In the kitchen, chef Priscilla Cavagliotti develops a cuisine grounded in regional, seasonal and direct-sourced ingredients. Her cooking blends alpine flavours with subtle global accents, producing dishes that are both comforting and contemporary. The approach is not to overwhelm but to distill: fewer components, sharper focus, more coherence with the landscape outside.

The supply chain mirrors the hotel’s ethos. Producers are local, collaborations personal, the menu adaptable to what the season offers. The tone is fresh and unpretentious: a cuisine that belongs to the valley but is ready to interpret it anew.

Matteo Mammoli