Huasco Valley: Villages and Communities Abandoned at the Edge of Chile’s Desert

Photographer Cristian Ordóñez explores, through images, the last communities before the world’s driest nonpolar desert capturing poverty, pollution, and lack of access to essential services in what is called the “Garden of Atacama”

Cristian Ordóñez: A Photographer of Place

Cristian Ordóñez’s aesthetic revolves around solitary scenes and suspended atmospheres. In his photos—whether in black and white or in dry, warm colors—there is no direct reference to a specific time or place. Instead, there’s a sense of disquiet, drawn from small yet striking details: a crack in a wall, a plant sprouting from concrete, an abandoned or half-destroyed building, and desolate landscapes. Born in Chile, Ordóñez is both a photographer and graphic designer whose work addresses themes of territory, belonging, and memory.

Although he characterizes his approach as documentary in style, he clarifies that he is not a traditional documentary photographer: “I’m not interested in merely documenting reality as it is. I like a certain amount of abstraction that allows for imagination, interpretation, and wonder.”

Ordóñez’s images appear unrecognizable and suspended, at a time when everything is expected to be immediately understandable and defined. His minimal, purposeful graphic design choices—he also handles the production of his own photobooks—reinforce this aesthetic. He uses design purely as a functional method to convey the content of his images rather than following trends.

Poverty in the Huasco Region

Ordóñez’s recent project, “Valle,” begun in 2022, focuses on a complex area of Chile: the Huasco Valley and its communities. The Huasco Valley is the last green valley before the vast Atacama Desert, the driest nonpolar desert in the world.

After the pandemic, the photographer and his brother—who is a researcher at Athabasca University in Canada—started exploring this area, traveling across the diverse environments of the so-called “Garden of Atacama.” From the Pacific Ocean to the peaks of the Andes, they visited many villages and interviewed local residents. As they drew closer to the desert, they noticed drastic changes in the landscape and, more significantly, in the worsening economic and health conditions. Communities are increasingly abandoned to poverty and pollution.

“There is a misconception around the concept of poverty and what it truly means. Sometimes we define poverty only by what people own or lack. But poverty also involves education and access to modern society. In several of our interviews, I sensed that poverty was, first and foremost, a lack of opportunities and access to universal services.”

Valle and Mining Activity

These areas have been left on the margins, with little social and environmental support. The Huasco River, which shares its name with the valley, is the last river to flow through this region, bringing life and vegetation. Beyond the encroaching desert and climate change, local communities also suffer from pollution and urban decay — initiatives that have persisted for years with little government intervention and, often, suspended projects.

“Some of these multinational projects are active, while others were active and have been cancelled for different reasons after several years., Those cancellations had happened by government interventions, after protests, environmental issues or other social events.”

The “Valle” project examines the four principal cities—Alto del Carmen, Vallenar, Freirina, and Huasco—home to around 72,000 people. Today, these communities largely rely on mining, which represents the region’s main source of income (around 41% of the regional GDP).

Cristian Ordóñez on Huasco’s Pollution

The Huasco Valley’s people and environment have been profoundly affected by the explosive growth of mining and related industries. Today’s climate and pollution issues stem from high levels of metal contamination in the Huasco River, which flows into the Pacific Ocean. This contamination affects livestock and food products, leading to serious health problems for residents.

“I learned from community members that they want more investment from the government and from multinational corporations, and that brings various risks to both the environment and the people. The community leaders also shared how they’ve lost many family members to pollution and the effects of mining.”

Amid these dire conditions, there are also local businesspeople who see mining as a source of production and growth for their land. The Huasco Valley has been part of several mining-related development projects in recent decades, many of which have been closed or abandoned due to the region’s social and environmental difficulties, even though they did create jobs for local communities.

The Huasco Valley Region

Different parts of the valley suffer from various forms of pollution, all not properly addressed by the Chilean government. Actually, Huasco has been declared a “sacrifice zone” which at list implies certain mitigation measures put there by authorities, even though they are not enough.

Near the coast, areas once inhabited mainly by fishers are now polluted by a power plant built on the Pacific shore. Despite this, Ordóñez describes the beauty of these places—where the Atacama Desert begins—as “a combination of the Pacific Ocean, dunes, and low hills surrounding roads and the coastal towns.”

Venturing further inland, you encounter oases along the river’s banks, hidden within the desert’s dryness and mountain ranges.

Cristian Ordóñez on Climate Change

Mining is most active in the four cities mentioned above. Approaching the Andes, mining companies frequently undertake public works—such as building schools, repairing roads, and providing jobs—as an easy way to gain favor and votes, consolidating their power in the region.

The economic benefits brought from mining remains while the damage to the microclimates—generated by the convergence of mountains and river—is irreversible. Such pollution raises issues shared across the entire country: namely, climate change, which we both cause and suffer from. Ordóñez highlights how climate change manifests locally in the Huasco landscape and how human activity is rapidly altering it.

A State of Ongoing Abandonment

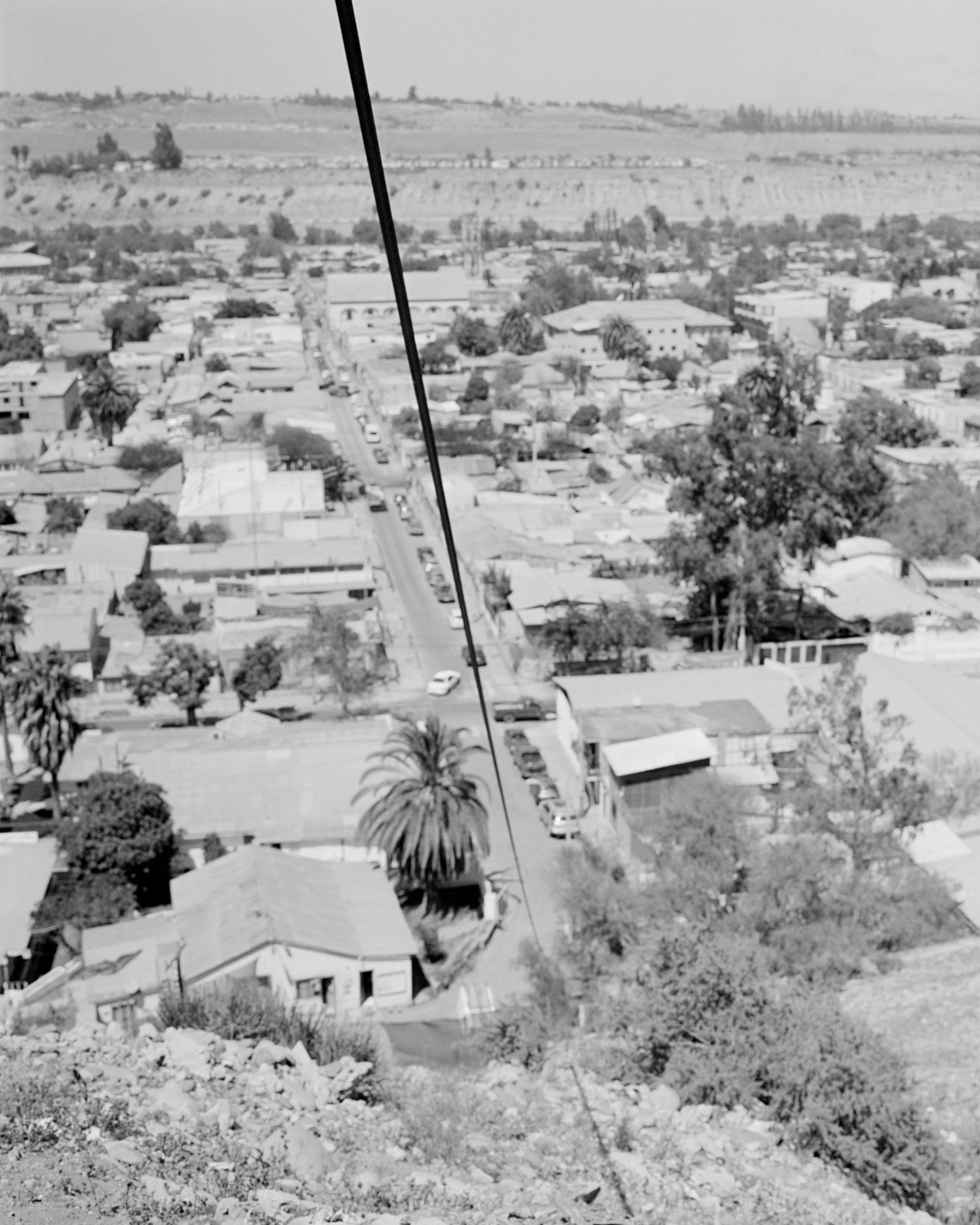

Ordóñez’s photographs depict towns in neglect and distress. Electrical cables for power, transportation, or telecommunications dangle overhead, unrepaired. Often, he places them in the middle of the frame, cutting the scene in two—suspended, unmoored references to the region’s isolation.

Connectivity, he explains, is another problem for these areas, which don’t dispose of all basic services, such as in provincial hospitals. The distances between towns can be deadly in a big emergency, due to the difficulty of receiving timely assistance.

In 2022, the photographer and his brother started documenting the Huasco region. They continued in 2024, extending their research into the Antofagasta Region and San Pedro de Atacama, where lithium extraction again brings its own set of challenges, repeating a pattern of exploitation in what was once a protected natural reserve in Chile.

Cristian Ordóñez

Born in 1976, Cristian Ordóñez is a Chilean photographer and graphic designer based in Toronto, Canada. His work explores themes of memory and belonging, territory and architecture, and everyday vernacular and banality.

In recent years, he has received the Edward Burtynsky Grant (Canada) and an Urbanautica Institute Award (Italy). His series “Frequency” was chosen for the 2023 Getxophoto Pause! Open Call (Spain), was nominated for the 2022 Leica Oskar Barnack Award (Germany), and was recently exhibited in a solo show at Galería Animal (Chile). He also self-published “Frequency” as a photobook in April 2023.

His newest project, “Valle,” created in Chile’s Huasco Valley in collaboration with Dr. Eduardo Ordonez-Ponce of Athabasca University, was recently shown in a group exhibition in Berlin and will be exhibited this year at the Rencontres de la Photographie in Gaspésie, Québec.

Claudia Bigongiari