The hottest title in Japan? Living National Treasure

First established in 1950, the title of Ningen Kokuhō – “Living National Treasure” – is given to artists who keep Japan’s traditional arts alive: it’s not the object that is protected, but the people

A public system for safeguarding craft: In Japan, the protection of traditional crafts is a responsibility of the state

In Japan, the protection of traditional crafts is a responsibility of the state and is anchored in the 1950 Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties. Under this law, bearers of important techniques – the so-called Ningen Kokuhō or Living National Treasures – receive an annual stipend and structured support to pass on their skills: funded apprenticeships, documentation projects, public demonstrations and talks. The system does not primarily defend objects; it protects the embodied expertise of the people who make them. To safeguard both quality standards and public budgets, the state maintains a limited number of designated holders, who are regularly monitored and supported as they train their successors.

Since 1974, a second, more industry-oriented track has existed alongside the individual title. The Ministry of Economy (METI) designates Dentō Kōgeihin, “traditional craft products”: today more than two hundred lines of production, including washi paper, urushi lacquerware, bamboo work, Arita and Bizen ceramics, and Nishijin textiles. To qualify, a craft must have at least a hundred years of history, be predominantly handmade, and rely on traditional materials and techniques. Designation opens the door to subsidies for training heirs, recording production processes, securing raw materials and stimulating demand through fairs, exhibitions and coordinated promotional strategies led by trade associations such as the Japan Kōgei Association.

A comparison with Europe makes the differences clear. In France, the Maître d’art title (introduced in 1994) formalizes a three-year master–apprentice path, backed by financial support and a national network for the métiers d’art. In Italy, by contrast, there is no equivalent national title. Safeguarding passes through inventories of intangible heritage and regional recognitions such as “Maestro Artigiano” – for example in Tuscany, with the Bottega Scuola scheme. These tools can be effective, but they are fragmented when seen against the integrated public infrastructure built around craft in Japan.

Ningen Kokuhō: Japan’s Living National Treasures

“Ningen Kokuhō”, Living National Treasures: the expression emerged in a country devastated by war and rapid modernization, at a time when many traditional arts were at risk of disappearing together with their masters. The response was a protection system designed not around objects, but around the people who still knew how to create them.

The Ningen Kokuhō title is perhaps the best-known recognition established by the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties. It is awarded to individuals who possess techniques considered part of Japan’s intangible heritage – from ceramics, weaving and lacquer to Noh and Kabuki theatre or metalwork. The state does more than celebrate their role: it provides financial support and actively invests in transmission, funding apprentices and ensuring that knowledge moves from one generation to the next.

Since 1974, the category of Dentō Kōgeihin (Japanese traditional crafts) has complemented the system of Living National Treasures. It now includes over two hundred crafts: from washi paper to urushi lacquer, from bamboo and swords to Arita and Bizen ceramics and the Nishijin textiles of Kyoto. Recognised crafts must have at least a century of history, be largely handmade and be grounded in traditional materials and techniques. Craftspeople gain access to research and marketing funds, take part in dedicated fairs and receive support from foundations and associations such as the Japan Kōgei Association, which organises exhibitions and competitions. Prefectures, in turn, develop their own registers and programmes.

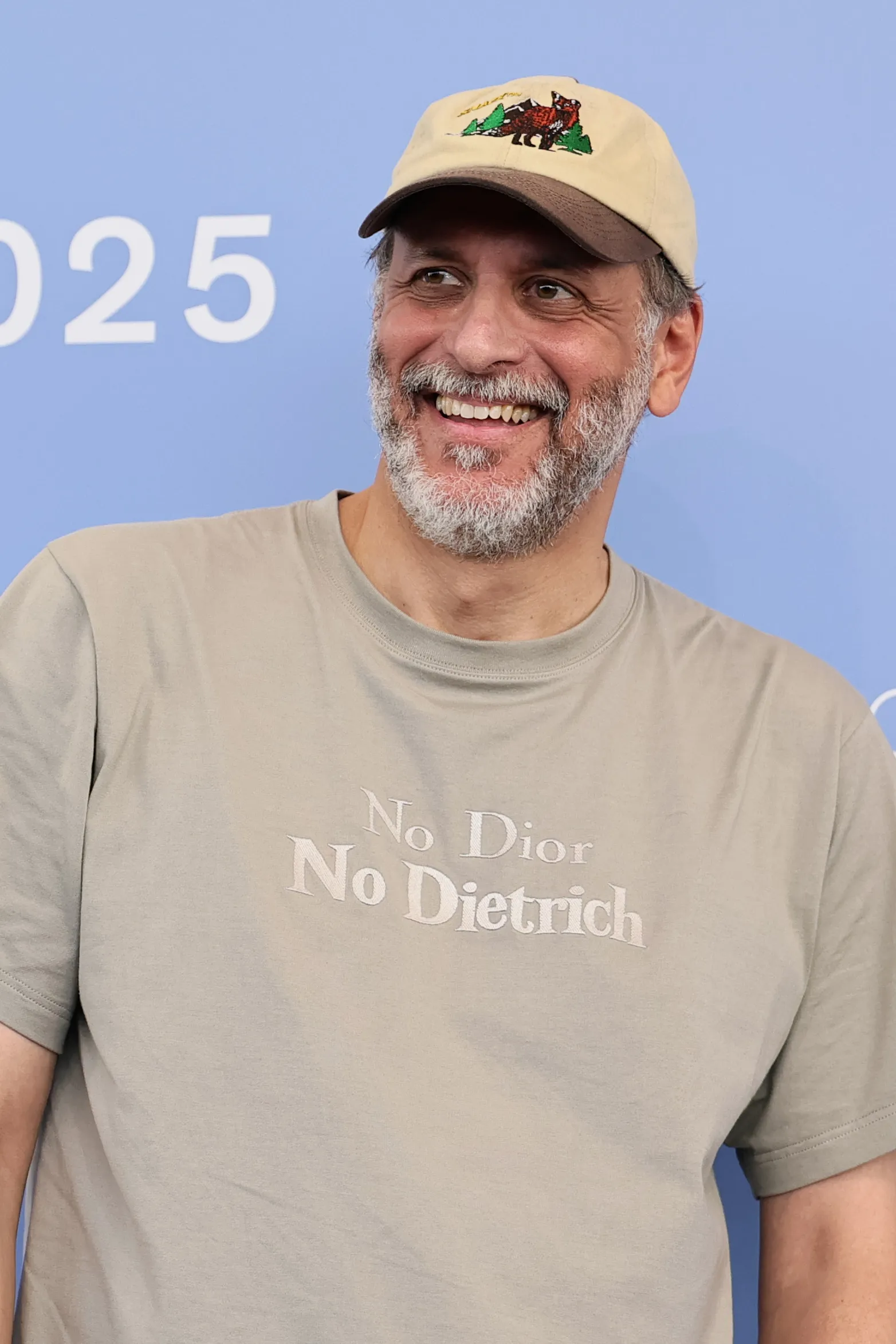

Murose Kazumi and the human commitment behind maki-e

Murose Kazumi was born in Tokyo in 1950. The son of a lacquer artist, he studied at Tokyo University of the Arts under two masters already designated as Living National Treasures, Matsuda Gonroku and Taguchi Yoshikuni. In the 1970s he began working independently; in 2008 he was named a Ningen Kokuhō for his mastery of maki-e.

Maki-e is rooted in urushi, the sap of the Toxicodendron vernicifluum tree. Tapped from incisions in the trunk, the sap is a milky, toxic substance which, after filtering and controlled exposure, becomes a hard, glossy resin. It is the fundamental material of Japanese lacquerware, used as a protective coating, an adhesive and a binder.

Maki-e is its most refined application. Fresh lacquer holds gold and silver powders that, once applied, are encapsulated beneath successive transparent layers of urushi. The repetition of these stages gives the image depth; light refracts on the surface, changing with the angle of view. This is a discipline that demands extraordinary human commitment: a single piece may require months or even years of work.

Human fragility: skin in contact with urushi

Before it cures, urushi can cause severe skin irritation. Apprentices quickly learn to recognize the risks, to protect themselves, to control the amount of direct contact. It is in this exposure that the human fragility bound up with maki-e becomes visible: the body is not external to the technique; it is part of it, with its limits and its capacity to adapt.

The work imposes slow rhythms, repeated gestures, held postures. Error is inevitable: a powder scattered a little too generously, a drying time too short, a polishing step taken a fraction too far. The finished piece still carries an echo of these tensions: the regularity of fields of color, the precision of contours, the continuity of reflections are the outcome of a delicate balance between the material and the body that works it. To be recognized as a Living National Treasure is not to embody an abstract ideal, but to show how fragile craft knowledge remains if it is not shared and passed on.

Natural raw materials: gold, sap and mother-of-pearl

Murose’s works are rooted in a constant relationship with natural materials. Urushi sap is collected only after years of growth, in small quantities and through carefully measured cuts. Gold and silver are ground into powders of different grain sizes, finer or coarser depending on the required effect. Mother-of-pearl is selected for thickness, cut into thin fragments and fixed with lacquer glue.

These materials dictate both the timing and the possibilities of the work: drying depends on seasonal humidity; the stability of the wooden core affects each subsequent layer; the iridescence of mother-of-pearl varies according to the direction in which it is cut. The visual result – a light that seems to well up from the depth of the surface – comes from a balance between natural resources and technical skill. Lacquered surfaces do more than reflect an aesthetic: they make an entire supply chain legible, from tree to metal, from shell to polished surface.

Objects built to cross centuries: a quiet sustainability

Once cured, urushi lacquer can last for centuries. Objects made more than a thousand years ago still retain their original shine. This durability is itself a form of sustainability: a piece that does not wear out quickly, that does not need constant replacement, but travels across generations with its function and beauty intact.

The pace of the workshop is deliberately slow: days of waiting for the lacquer to harden, patient and measured polishing. Museum conservation follows equally long-term protocols: control of light, humidity and temperature. Everything is organized to preserve what has been made. Each work thus establishes an intergenerational pact: the person who makes it today is working for someone who will encounter it tomorrow. Here, sustainability means responsibility towards the future, measured in years rather than seasons.

Tatsuzō Shimaoka and the echo of Jōmon ceramics

Tatsuzō Shimaoka was born in Tokyo in 1919. After studying at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, he apprenticed with potter Shōji Hamada, a key figure in the Mingei movement, which valued folk crafts as authentic expressions of Japanese culture. In 1954 Shimaoka opened his own kiln in Mashiko, a town with a strong ceramic tradition; in 1996 he was designated a Ningen Kokuhō for his Jōmon zōgan technique.

Zōgan involves cutting incisions into the clay surface and filling them with a contrasting clay body. Shimaoka combined this inlay process with the rope-pattern motifs of Jōmon pottery, which dates back over ten thousand years. Cords pressed into the clay leave deep grooves into which white clay or light glaze is inserted, contrasting with the darker body of the vessel. After firing, the surface shows a raised pattern that merges archaic roughness with the delicacy of inlay.

His work consists of everyday objects – cups, plates, bottles – in line with the Mingei ideal that refuses any strict separation between art and utility. The Jōmon echo is not a decorative quote but a structural principle. Repeated marks modulate the grip; light rests on the ridges; the glaze highlights every tiny variation in the surface: a slightly thicker area, a deeper groove, an imprint that is less pronounced. These minute differences become perceptible after firing, both to the hand and to the eye.

Akihiro Maeta: the silence of white porcelain

Akihiro Maeta was born in Tottori in 1954. He trained in the Hakuji porcelain tradition, characterized by completely white surfaces and developed a highly personal approach that led to his recognition as a Living National Treasure in 2013. His distinctive choice is to shape every piece entirely by hand, without using the potter’s wheel.

His porcelain pieces carry no ornament. Form itself becomes the language. Working by hand means repeating the gesture until the curve is uninterrupted, the wall thickness is even, the rim is visually and tactilely stable. It is a grammar of proportion that turns the maker’s body into a measuring tool.

White does not conceal; it reveals. Slight variations in thickness emerge after firing; internal tensions can be heard in the sound of the material; light traces the profiles with sharp edges. The “silence” of his work is not emptiness but extreme concentration: every repeated smoothing, every controlled surface speaks of a search for formal coherence. His poetics lies in the repetition of similar vases, where the gesture, more than any decoration, defines the identity of the piece.

Nobuo Matsubara and the breath of indigo

Nobuo Matsubara was born in Tokyo in 1940. After his studies, he devoted himself to traditional dyeing, specialising in the Nagaita-Chūgata technique, which uses hand-cut paper stencils and indigo pigment. In 2023 he was designated a Ningen Kokuhō as a guardian of this textile practice.

Nagaita-Chūgata employs long wooden boards on which the cloth is stretched. Hand-cut paper stencils are used to apply a paste of rice flour – nori – that protects certain areas of the fabric. The cloth is then dipped repeatedly into indigo vats, with intermediate drying periods and precise realignment of the pattern. The resulting blue is never perfectly flat: it vibrates, moves with the fiber, reflects the subtle variations produced by the fermentation of the plant.

In Matsubara’s kimonos, traditional motifs coexist with tiny deviations born from the direct encounter between pigment and fiber. The technique evolves without fanfare: by adjusting the density of the paste, the immersion times, the length of drying intervals. The supply chain can be read from start to end: cultivation of the plant, preparation of the dye, disciplined work in the studio. The “breath” of indigo accompanies every step, turning the cloth into a surface that speaks as much of tradition as of the present.

Tradition made present, without rhetoric

Tradition here is not a static repertoire of motifs; it is a method. Murose Kazumi brings time and gesture into lacquer; Shimaoka shows how clay records marks; Maeta strips everything back so that form can emerge; Matsubara uses indigo to tell a story of immersion, drying, alignment. Four distinct languages, one shared responsibility: to make what they have learned visible to others, to turn competence into teaching, to accept that the work will outlive its maker.

In Japan, this institutional infrastructure has turned continuity into a public responsibility. There is no comparable nationwide system in Italy, where recognition is still fragmented across local and regional levels. France, on the other hand, has since 1994 awarded the Maître d’Art title, managed by the Ministry of Culture, which operates in a way similar to Ningen Kokuhō: recognition comes with financial support and a concrete obligation to pass knowledge on to disciples.

Ningen Kokuhō

In Japan, Ningen Kokuhō – Living National Treasures – are individuals designated by the state to safeguard and transmit skills that might otherwise disappear. Among them are figures such as Murose Kazumi, who carries forward maki-e on urushi lacquer; Tatsuzō Shimaoka, who fused traditional ceramics with Jōmon rope patterns; Akihiro Maeta, who hand-shapes white porcelain; and Nobuo Matsubara, who dyes cloth with indigo using stencil techniques. Tradition survives in the everyday practice of those who continue to repeat it – and to teach it to future generations.