Lake Como Design Festival: waste, work, and the life of materials

The seventh edition of Lake Como Design Festival examined waste, material honesty, and circular practices, showcasing how designers rethink resources today

Lake Como Design Festival 2025: Fragments as a way of reconstruction and reconnection

Lake Como Design Festival returned to Villa del Grumello for its seventh edition from September 14 to 21. The theme this year was called Fragments. It was in the works, in the materials, in the traces left behind. Stories, visions, memories, but mostly pieces of materials, of nature, of waste left over by human activity. Every object carried evidence of its origin—what it was, what it became, what it might still be.

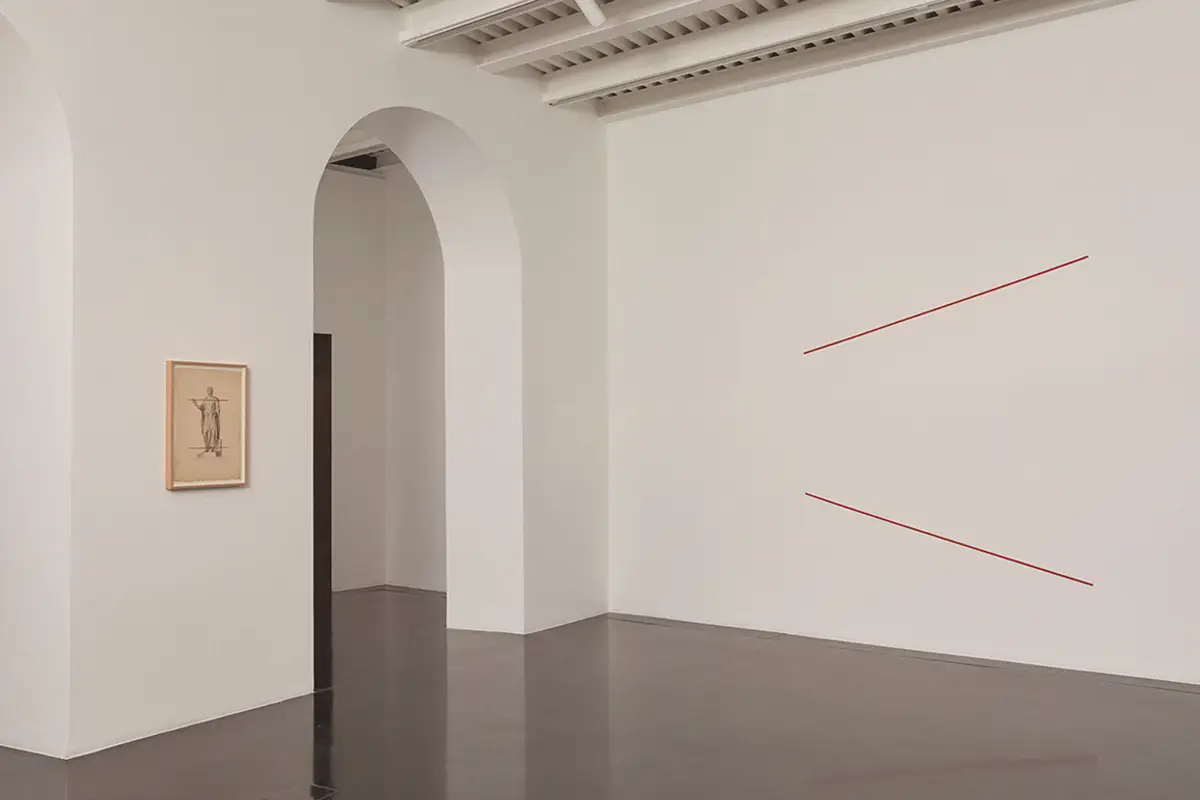

At the center of the exhibition was the 16th-century villa, standing tall on the shores of Lake Como. From works by Enzo Cucchi to Archivio Mantero and Campeggi’s Vico Collection, the house displayed physical and metaphorical manifestations of fragments—craft that’s raw and functional. The surrounding greenery extended the exhibition with the Contemporary Design Selection. Grumello Park housed contemporary works that continued the narrative, adding a more recent consciousness to the principles of design. The installations weren’t gathered in one place. They’re spread across the park, between trees and slopes, traceable through a map. Some almost disappeared into the setting. They didn’t impose on nature. The work was there, but it didn’t demand to be seen.

The villa itself was quiet. No crowd, no background noise. The absence forced you to look at the works directly. Nothing else distracted. Just objects in space. What remained was the encounter itself: if a work had weight, it held up under silence. Many pieces were unfinished. Rough edges, exposed textures, recycled surfaces. Glass showed shards, stone showed fractures, wood bore marks of use. Nothing polished to hide its origin. Materials already exist—they carry their history.

Heritage and craft preservation: Sustainability as knowledge, craft, and technique preservation by Archivio Mantero at Lake Como Design Festival

The villa welcomed with the display by Archivio Mantero, following Enzo Cucchi’s ceramic fusion of sculptures and paintings. The textile industry in Como has been a production system for more than a century. Mantero, founded in 1902, is one of the houses that shaped that system. Today, the archive holds 80,000 accessories, 100,000 printed and jacquard fabrics, 30,000 hand drawings. Printing tools, books, photographs, and garments from across the world complete the collection. Two hundred years of textile practice concentrated in one place.

For Lake Como Design Festival, Archivio Mantero presented its archive at Villa del Grumello through UNANNO—an installation marking the archive’s first year as an independent project. At the center stood the oldest volume in its collection, printed textiles dating back to 1820. Around it, a photographic record and a soundtrack documented the archive’s first year of activity as a platform for design and research. A fanzine, also titled UNANNO, was produced to extend the installation into print. An example that sustainability extends beyond the material. It’s also the act of keeping knowledge, processes, and archives alive. It requires maintenance, cataloguing, editing, restriction.

The Mantero archive shifts the focus away from endless production toward reactivation of what already exists

Every new product in the fashion and design industry is tied to resources—cotton, silk, dyes, labor, logistics. The Mantero archive shifts the focus away from endless production toward reactivation of what already exists. Instead of generating new patterns for the sake of novelty, the archive invites reinterpretation, adaptation, critical study of two centuries of textile culture. This sets limits on waste at the conceptual level: new ideas are not extracted from raw resources. They come from the reuse of existing cultural capital.

There is also a structural responsibility in how the archive is managed. Selective access avoids overexploitation. Restricting entry to those with a precise project prevents the archive from being drained into disposable trends—a working system with longevity.

Sustainability here does not look like recycling bins or biodegradable materials. It looks like a refusal to discard craft and history. The methods of weaving, printing, designing stored in the Mantero archive are part of a production ecology. To maintain them, to keep them accessible under controlled conditions, is to avoid cultural and technical waste. If raw materials can be reused, so can processes. In a market that consumes memory as fast as fabric, this preservation is itself an environmental stance.

Rationalist architecture and resource efficiency: Asilo Sant’Elia in Como

Another site for the design festival was Asilo Sant’Elia, a building that embodies the core principles of Italian rationalism. It hosted the Piccoli Razionalisti project by Wonderlake Como. Academia dei Piccoli Artisti was an official collaborator. The involvement of the academy is connected to its focus on rationalism, with over 1,400 primary school students exploring Como’s rationalist architecture during the 2024/25 school year.

The Asilo Sant’Elia was built between 1936 and 1937 by Giuseppe Terragni, whose portfolio includes rationalist buildings in Italy—Casa Del Fascio, Novocomum, Casa Rusticito. Initially built as a kindergarten, it was designed to serve the new working-class district of Como. The structure is simple: masonry walls supported by a reinforced concrete frame. No decorative excess, no superfluous gestures. Just solid blocks and large windows cut into them—voids designed to bring in light and connect the inside to the gardens.

Asilo Sant’Elia has often been read in parallel with Terragni’s Casa del Fascio

The building has often been read in parallel with Terragni’s Casa del Fascio. The difference here is scale—the kindergarten rests entirely on one floor. The glass walls extend the idea of the open-air school, opening classrooms to the landscape. Inside, the plan is carefully organized; even the furnishings, many designed by Terragni himself, follow the same discipline of clarity and function.

Beyond aesthetics, the structural clarity of Asilo Sant’Elia is resource discipline. What Terragni achieved through proportion and clarity is what sustainable design now calls passive performance. Resilience here does not mean flexibility in style or program, but in the endurance of its structure. The form is stripped to what is essential—what makes it adaptable by default. The concrete skeleton does not dictate one function forever. It provides a framework that can host different uses across time. The materials endure without the need for constant maintenance or substitution. Nothing has to be stripped back, dismantled, or rebuilt for the building to live again. Even in abandonment, the structure holds itself together. It carries the possibility of reuse in its very bones.

Rationalist architecture reduces form to its barest essentials, and in doing so reduces waste. It proves that efficiency can be aesthetic. Asilo Sant’Elia channels that principle—every element is intentional, reduced to what is necessary, every material carries weight and purpose. It invites repurpose and reuse through time, without structural waste.

Reuse of construction and natural waste at Lake Como Design Festival

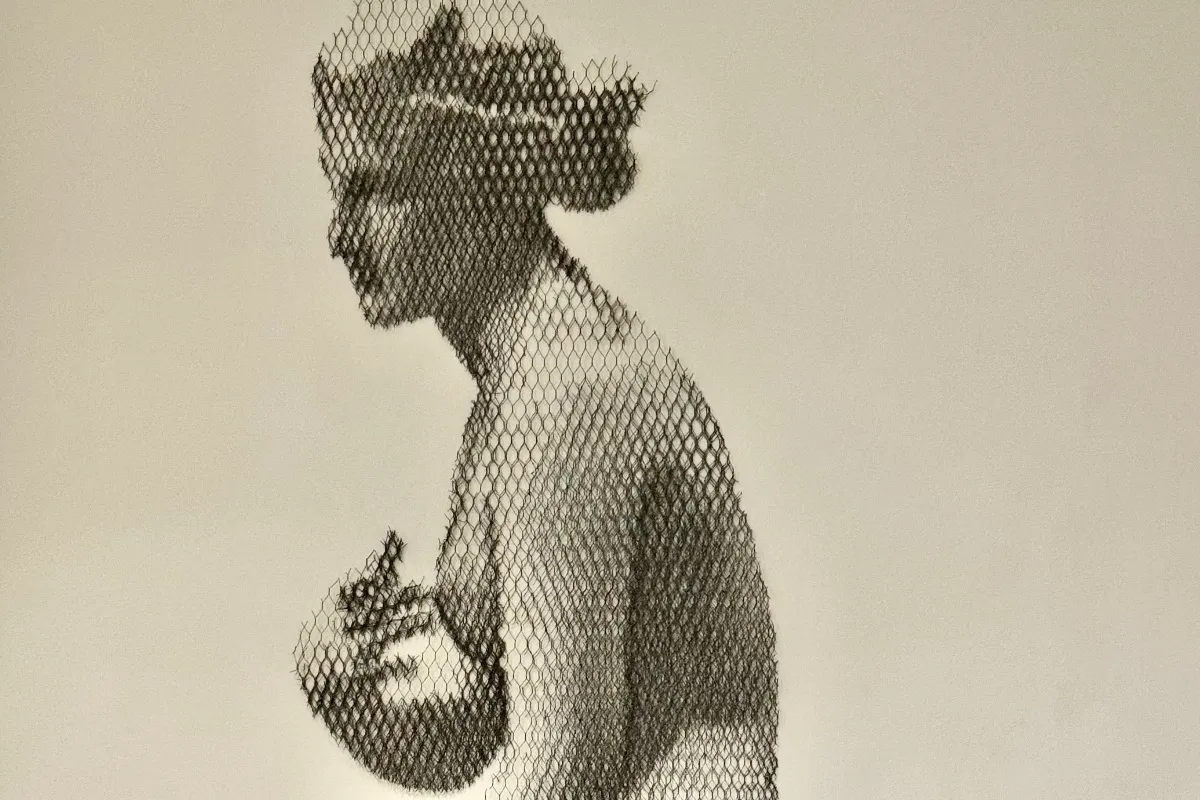

Waste is the one material design never runs out of. Piles of marble scraps in industrial ‘cemeteries,’ plaster blocks from demolitions, furniture carcasses dumped on city sidewalks—at the Lake Como Design Festival, several works stepped directly into the mess. Not disguising or romanticizing, they collect, bind, cut, reassemble the fragments. The goal is to give them a new cycle of life. This is what many contemporary works achieved.

Part of Capriccio, Iranian-born Payam Akari and Omniaworks presented their Remains project—an exploration of the theme of fragments through furniture design made from marble remains. The work dealt with marble by-products: shards and slabs that had accumulated as collateral of centuries of extraction. The pieces were not polished away. They were locked in resin, suspending irregular shapes and mineral colors inside layered blocks that were then cut back into slabs. The result was a three-dimensional terrazzo, industrial and heavy, where the scale of marble waste became visible and functional. The method was direct: collect, bind, re-cut, reuse. Resin acted as the glue, aluminum as the structural counterweight. Together, they created a hybrid surface strong enough to become shelves, tables, panels.

Georg Foster displayed Fractions, a series of burnt wood objects made from off-cuts that would have been discarded

Close by, Georg Foster displayed Fractions, a series of burnt wood objects made from off-cuts that would have been discarded. Each piece followed the natural cracks, knots, and splits of the timber, with minimal intervention and joinery defining function. Fire was used to soften edges and enhance texture, highlighting the wood’s imperfections instead of hiding them. Traditional off-cuts, often twenty to fifty percent of processed timber, became trays, candle holders, and surfaces, with every fragment given a new purpose. Waste became design, irregularity became structure, discarded material was transformed into functional objects.

From marble and wood to travertine, the use of wasted natural materials continued with the Surfaced: Amphisbaena installation designed by Sho Ota. Made in collaboration with Italian fabricator Bianco67 and curated by Agglomerati, the five-metre installation was placed in front of Villa del Grumello, in between the house and the lake. It was designed to replicate the shape of the mythic amphisbaena serpent, which had a head at each end, capable of moving in both directions. The installation was made entirely from architectural debris—unused travertine offcuts once meant to be used for the Vatican.

LoungeChair by Flatflat: American designer Aidan Reinhold used furniture waste from the streets of New York City

The theme of reuse continued with works that embraced the recycling of waste, with LoungeChair by Flatflat, for which American designer Aidan Reinhold used furniture waste from the streets of New York City. The final product, made from aluminum, is designed to fold in seconds and be moved around with its owner. It’s recyclable, lightweight, and resistant to bending—intentionally designed to be moved and used for a long time. A similar process was behind Mirach – Andromeda Series by PLASMA-f and Frigerio Marmi e Graniti—a project that explored the reconciliation of waste and form, using only marble scraps and leftover slabs to create coherent, functional pieces. The project turned industrial leftovers into deliberate, structured objects, making visible the connection between consumption, material remnants, and design.

Reclaiming and holding onto resources was also behind the Resourcer bench by Atelier Thomas Serruys. Placed outdoors near the villa, it served as an invitation to engage with material and memory: the seat, cut freely from reclaimed steel, rested on forged legs shaped like suction cups, holding fragments together and unifying them into a single functional piece. Waste became structure, and structure became use.

Rawness and material honesty: A core principle at Lake Como Design Festival

Beyond all, Lake Como Design Festival was a celebration of the material in its rawness, complexity, and the story behind it. Every work told a story through texture. Engaging with the material was not only permitted but encouraged. Without it, the story was incomplete. Decoro Mediterraneo, for example, a carpet by Eleonora Todde, invited the viewers to walk on it barefoot and experience the fibers physically. Material honesty was at the heart of every installation, making the story of each work inseparable from the story of its substance.

This principle extended across the festival. Matter Forms and Atelier WAMA presented Remnants of Reflection, exploring fragmentation as a catalyst for transformation. Oyster[Crete]® and reclaimed metal were combined to form a monumental table rooted in material memory. Welded offcuts of metal interlocked without traditional joints, leaving raw edges and layered textures exposed. Traces of erosion, sediment, time remained visible, honoring the origin of every element. The work resisted industrial uniformity, making every outcome singular and irreproducible.

Georg Foster’s Fractions kept cracks, knots, and splits in wood visible, with minimal intervention. Each object followed the timber’s natural lines, letting imperfections dictate form and function. Surfaced: Amphisbaena left seams and joins in travertine offcuts exposed, showing the process of assembly rather than hiding it.

Plaster salvaged from demolished buildings

A similar principle was used by Lucie Gholam. Displayed in Serreta, her Plaster Ruins – Vanity and Table repurposed plaster salvaged from demolished buildings. The works retained rough, unfinished surfaces, confronting the passage of time and the crudeness of a material often hidden or discarded. Vanity and Table juxtaposed nostalgic forms with raw materiality, turning demolition fragments into functional, tactile sculptures.

Studio Lilium’s Ayumi lamps showcased handmade paper textures and cocoa bean fragments. Texture was the language of the pieces. Irregular pleats and visible fibers emphasized the crafting process. The embedded cocoa fragments added subtle color, scent, tactile depth. Every lamp highlighted the material’s life and origin, inviting engagement with the physicality of the object.

Functionality and circular design: Designed to move and adapt

Another core principle at Lake Como Design Festival was circularity in action: works designed to last, to adapt, to move through multiple lives. Verstrepen.studio’s Contemplation Bench embraced circularity through material and function. The bench combined a recovered slab of black schist from Belgium with a simple aluminum frame, creating a piece that could serve both as a seat and a small table. Each stone was manually recovered and decontextualized—this turned an ordinary material into a multifunctional object. The designer’s manifesto framed the collection: a critique of overconsumption, an embrace of craftsmanship, a commitment to sensory experience. Every element was intentional, demonstrating that circularity is also about design that anticipates longevity and adaptability.

Flatflat’s LoungeChair, beyond its reuse of materials, embodied this approach as well. Born from the designer’s experience of frequent moves and the excess of discarded furniture on New York streets, the chair folds up in seconds, is lightweight, corrosion-resistant, recyclable. It is made to travel with its owner, extending its usefulness instead of being left behind to waste.

Studio Lilium’s Ayumi lamps closed the loop on functionality with biodegradable construction and careful material choices. Hand-pleated paper, embedded cocoa fragments, traditional Japanese techniques—these created objects meant for long-term use, where the story of the material remained visible throughout its life.

Fragments, the seventh edition of the Lake Como Design Festival, was an exploration of roughness as a functional and material principle. The works exposed their textures, construction, and origin, showing how design can reuse, preserve, and extend the life of materials. The quiet setting allowed each installation to speak through material, making process and function the primary form of expression.

Susanna Galstyan