Lampoon, the new issue, a tribute to the independent publishing: roughness and sustainability

The new issue of Lampoon is a tribute to independence: in publishing, music, and architecture. From Romain Laprade to Olivier Zham, from Joel Dicker to Caterina Barbieri, Mathis Chevalier, Isabelle Albuquerque

Lampoon, a rough magazine – nothing extraordinary

Lampoon is a rough magazine. A roughly embossed cover, frequently analog photography, with minimal post-production. No excuses, no retouching. The same goes for writing: sixty to eighty journalists worldwide – in different languages, publishing with us in English or Italian. They write following our editorial guidelines: adjectives are banned, adverbs are banned. Words like important or essential are banned. Superlatives are forbidden, and the term extraordinary is perhaps the most despised – who can presume to define what is ordinary and what is extraordinary? What counts lies in the ability to recognize a detail. We want everything to be edgy, lean, like a natural fiber. We look for the scratch.

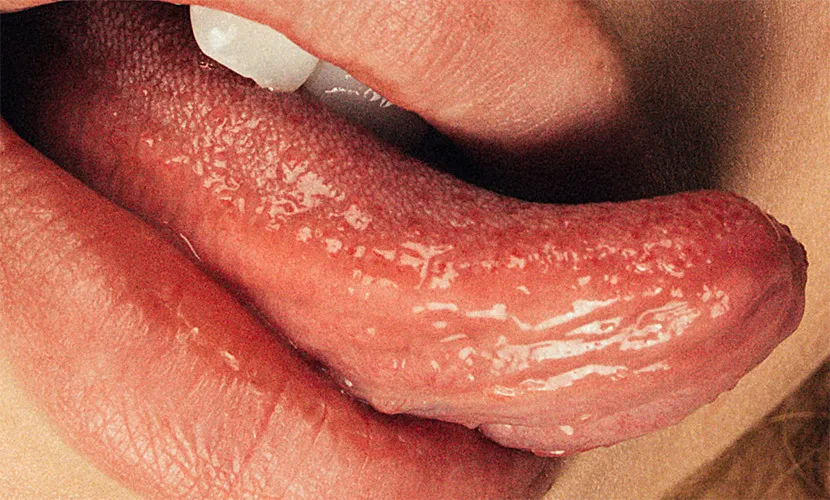

We hate plastic; we want skin

There is nothing we hate more than plastic. Synthetic fibers – polyester, viscose, elastane. Far too much of what we wear is made by mixing synthetic fibers with natural fibers, stuffing them with polyurethane to make them soft, trapping animal feathers in plastic cells so they can’t escape. We need to start choosing clothes that don’t contain plastic: fabrics that let the skin breathe; when we sweat in plastic, our skin smells off – something rancid. Our skin, human skin, when sweating, releases salt, earth, water, sweat, blood. Plastic makes everything smooth, compact, solid – but we like the hard and the naked, the rough, layered, pornographic, dirty, honest human soul. Plastic is necessary in hospitals – that we respect.

Roughness and no adjectives

Affection and softness can exist, but roughness remains. Roughness is a form of authenticity, honesty. When you start smoothing something up, wrapping it, you partly surface or kill it. Roughness is raw material. Rough means unfiltered. A rough world doesn’t need captions – it works without instructions. If a sentence includes an adjective, try removing it; if the sentence doesn’t hold up without that adjective, then remove that sentence itself to need the next one.

We looked for people, talents, who could talk about independent without labeling it. One chapter is dedicated to a project by Romain Laprade, who joined us in Rome to explore irrationalist, modernist buildings – an unexpected imagery for Italy’s capital. A long conversation between me and Olivier Zahm, editor-in-chief of Purple Magazine for over thirty years, discusses independent publishing in art and fashion. Joel Dicker – after Bernard de Fallois passed away, he decided to publish his books himself, launching his own publishing house instead of going through a large group. Caterina Barbieri, Mathis Chevalier, Isabelle Albuquerque – and more.

Independent publishing: what does it mean?

Independent publishing. What does it mean? It means coherence. By definition, publishing is the industry that spreads an authorial expression: a text, a photograph, a video. Authorial, because it conveys the personal experience of its creator. Compared to standard publishing, independent publishing must go a step further: authorial expression succeeds in carrying a message. Civil, ethical – even political. Independent publishing defines and reveals itself through consistency with that message. Such coherence must take priority over commercial, diplomatic, and financial strategies.

Lampoon’s message: sustainability is the only viable form of contemporary culture.

Lampoon is the cultural magazine dedicated to sustainability. Taken individually, these two words sound generic. Culture means curiosity. Sustainability – that unknown – can be understood in its broad sense of human respect, to the point that any civic commitment might fall under its umbrella. Sustainability means civilization – but it runs the risk of becoming so generic that it loses bite. Lampoon works on the intersection of these two terms: the culture of sustainability; sustainability as the only form of contemporary culture.

Sustainability in manufacturing, in production: we must ask questions about everything. An artist, a craftsman, an exhibit, a setup. The color black. Light and energy. A piece of furniture – wood, concrete, marble. A weekend trip when we drive eight hours, just to spend barely twenty-four hours awake by the sea. When we take too many flights, turn up the heat, do our grocery shopping, open our wardrobe. We must learn to look at everything around us through the lens of human respect – which, yes, means sustainability. The culture of sustainability – because sustainability becomes our intellectual ability, a filter in our minds: we need to understand, to observe, thinking about what impact each thing might have.

There is no artistic, narrative, or curatorial expression that makes sense today unless it asks how we can live together without harming one another. With thinking about what we’ll be living in July 2040.

Drill, baby drill is not progress. It’s nothing

The word sustainability is polarizing: some believe there’s nothing else to discuss, share, or publicize – that includes me, writing this, and an army of young people terrified for their future. On the other side, there are the boomers. By boomers, I don’t just mean those born in a certain decade of the twentieth century. I mean everyone, of any age and background, who lives with past the only measure. There is no progress without sustainability: drill, baby drill is not progress. It’s nothing. Boomers are everyone still convinced that sustainability doesn’t interest anyone – and if they must address it, for work or appearances, they do the bare minimum.

Sustainability is a compromise; independent publishing is a compromise

Up to this point, it’s all theory. In practice, sustainability is merely a compromise. I feel almost obliged to say that everything set out above is a utopia, the delusion of someone hoping to do something useful in a lifetime. Temperatures rise because the oceans are warming – and microplastics are part of that warming. The oceans are full of plastic – one possible solution might be a genetically programmed bacterium to digest it, with who knows what side effects. The textile industry, the cosmetics industry, tire usage – these are the major culprits for microplastic dispersion. The problem of microplastics in water almost makes the issue of carbon and air pollution look second.

What can we do? Concretely, I mean – what can a group of human beings do who’re trying to hold on the battlements of independent publishing, continuing to repeat above and wondering how pointless it might all be? What can we do, when we must accept compromises every day, compromises that turn into contradictions, making us feel like ants on a slick mirror, falling and muddying our ground?

We want reaction, conviction, illusion. We collide with walls, we plunge into abysses. We say naive, nostalgic, aroused, drenched, furious. We’ll take anything to free ourselves from that sense of finish we feel when we stand there like fools, scrolling a phone screen. Let’s use that finger for more intuitive purposes. Searching and shouting, we cry. And we will keep publishing words of honesty and roughness. Ten years have passed since 2015, when the first issue of Lampoon was released. The world is still ours, my love.