The Rough Voice of a Rough Woman: Maria Callas by Angelina Jolie

The roughness of voice and character in Pablo Larraín’s Maria, a biopic on Callas portrayed by Angelina Jolie

Maria, the Rough Voice—Singing Should Never Be Perfect

Maria Callas refuses to listen to the recording of her voice on the record. We’re halfway through the film: the scene unfolds in a Parisian café, with the sign “Acapulco” out front. It’s late; Maria is the last patron of the day, and the place is about to close. At the counter, the bartender reassures her, telling her he’s called her home so the butler can come pick her up. Maria is in the grip of hallucinations, under psychiatric medication, perhaps unaware of her surroundings. The bartender wants to pay her homage and turns on the record player, raising the volume as Callas’s voice fills the empty salon. Maria shifts from a subdued pose to that of a rough, snarling tigress; she raises her voice, demanding he turn it off, to stop the record. A woman whose voice has been recorded on a million vinyls tells the man that no, singing should never be halted by a record, because on a record, singing becomes perfect—and singing must never be perfect.

Callas’s voice was not that of an angel—perhaps more like an animal, a beast that might inhabit Paradise but a beast nonetheless. Navigating through the notes, she brushed against guttural sounds, scratches, slaps. A rough voice that broke in the nasal passages. A voice born from the depths of the gut, propelled by muscles, blood, rage, and sap: the diaphragm provided strength like a torsion. Later in life, when study and rigor waned due to the distraction of her love for Onassis and the high-society life with which he besieged and conquered her, Maria offered clinical explanations for her uncertainties in singing: spasmodic intestines that blocked the diaphragm, robbing it of strength; cavities closed by inflammation; sore shoulder muscles. According to Camilla Cederna’s writings, doctors viewed Callas’s pharynx as an anatomical marvel embedded in a muscular and parasympathetic system weakened and humiliated.

Meneghini-Callas on Via Buonarroti and the Comparison with Tebaldi at La Scala in Milan

During her successful years, Maria Callas lived in Milan on Via Buonarroti and was married to Commander Battista Meneghini. They were married for ten years, loving each other like children—in the car returning from Verona, the couple wanted to stop at the edge of the woods to sneak in and share a kiss. Caprices, rumors, gossip—love or not, the Meneghini-Callas couple was a business partnership: Callas would later declare that of her marriage, eight of those ten years were spent in the whiteness of the bed. Commander Meneghini managed her career as her impresario, trying to tone down the flirtations between Maria and Renata Tebaldi. For instance, in an interview with Time, the rough Callas said, “Comparing me to Tebaldi is like comparing champagne to cognac—or rather, to Coca-Cola.” Tebaldi responded, “We all know how even champagne, over time, turns to vinegar.” In Pablo Larraín’s film, the feud with Tebaldi doesn’t appear, nor does much of Callas’s life in Milan, except for a few fragments at La Scala, both outside and on stage.

Angelina Jolie at La Scala—Reproducing Callas’s Voice

A technician from La Scala was present during the film’s shooting. He recounted that, to enhance her performance, Angelina Jolie had learned the pieces and the singing, and on stage, she used her own live voice. She sang the parts to better act them—then the sound was merged and evolved to incorporate the restored recordings of Callas’s concerts and contributions from a professional soprano. There is no unanimous opinion or certainty about the methods used, but it’s reasonable to suppose that technology blended different sources, processing them into a result consistent with Callas’s original timbre. In the film, when Maria’s voice is weakened, when she encounters overly raw off-key notes, it seems they used recordings from her concerts in Japan, when her voice was fatigued.

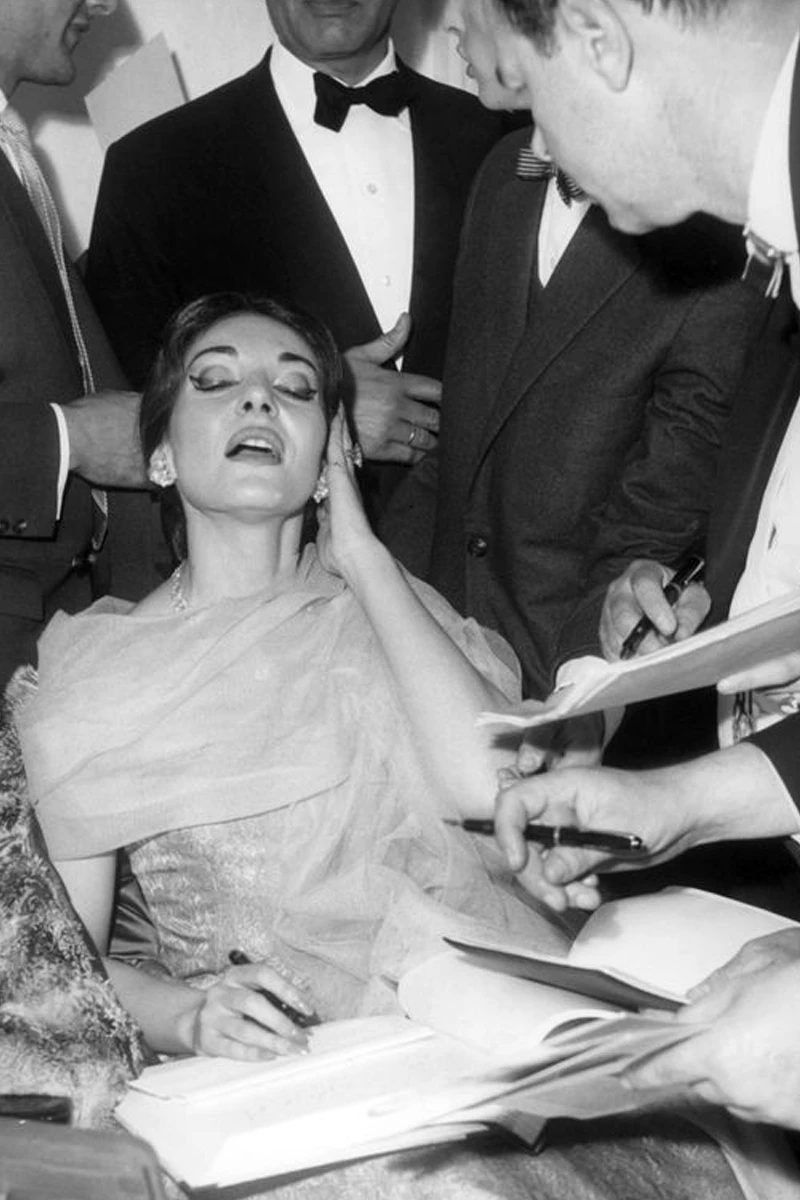

Angelina Jolie in Venice for Maria, the Cartier Chalcedony Brooch, the Veins of Her Hands and Forearms

Arriving in Venice on the morning of August 29, Angelina Jolie wore a Cartier brooch: a leopard with emerald eyes and black lacquered spots, perched on chalcedony. Chalcedony is a translucent quartz, one of the twelve gems given to Moses on Mount Sinai. In magical practices, chalcedony is a remedy against nightmares and fantasies. The brooch dates back to 1971 when Maria Callas purchased it from Cartier. Angelina Jolie wears it in a scene in the film and wore it when she presented to journalists that morning. She donned a sleek black dress to showcase the brooch—but in some photos, her hair slipped over her shoulders and covered it. In other photos, one can notice Jolie’s wrists and the veins of her forearms. Even more evident are the veins on her hands. In images taken later that evening, upon her arrival for the first public screening, her thinness is noticeable, her red lips, the tattoos—and again the veins, honest and sincere yet nervous, that pulse when Jolie touches her fingers or, while walking, holds her hands behind her back.

The Thinness of Maria Callas and the Legend of the Tapeworm

It was part of her portrayal of Maria Callas: Jolie, entering the cinema hall in Venice, was once again embodying Callas. Nervous, fragile, rough—a steady smile, fatigued in her beauty, adorned with jewels, while those veins on her hands and beneath her skin were cinematic graphics. There is only one diva—Maria Callas—revived in Angelina Jolie. Her thinness caused a stir and clamor in the 1950s. Maria Callas had become famous on stage weighing 90 kilos, with plump cheeks, the soprano’s double chin, ample bosom. Just a year later, she reappeared on stage at least 30 kilos lighter. From America, journalists telegraphed Camilla Cederna to find out what diet Callas had followed, which doctor had treated her, and in which clinic. It remained a mystery—except for a legend, to be taken with a grain of salt, that fueled the myth. It seems Callas, along with a glass of chilled champagne, had ingested a larva—the Taenia, commonly known as the tapeworm—which devours the food ingested by its host. There’s no certainty about this.

Teatro dell’Opera in Rome, Maria Callas, Norma, January 2, 1958

In those years, debate over the world of opera was as heated as today’s stadium discussions. Callas was a divisive figure due to her rivalry with Tebaldi. Two factions—for Callas or Tebaldi—just like Lazio or Roma, Inter or Milan. Rome or Milan—the two locomotives of Italy, compared and in rivalry. Callas was the emblem of La Scala in Milan; when she arrived in Rome, she was “the Milanese,” said with a derogatory tone. Snobbish like the entire northern city, capricious, sullen, and gloomy like the Po Valley fog. Callas took the stage at the Teatro dell’Opera in Rome for Norma on January 2, 1958. A gala evening, invitations in the stalls, paying public in the gallery, and President Gronchi in the royal box. During the first act, her performance of “Casta Diva” earned her a whistle from the gallery, immediately covered by encouraging applause from her most faithful.

At intermission, in her dressing room, Callas fell into irritation and perhaps fury: she said she wasn’t well and that she would not sing anymore, that for no reason would she return to the stage that night. The theater did not have, as it should have for a night like that, a standby performer. The opera was interrupted; President Gronchi left. People on the street railed against Callas, who had to escape through an underground passage, taking refuge at the Hotel Quirinale. There was a parliamentary inquiry. The news and scandal traveled to Paris, London, New York. The whole world talked about it. Perhaps that night marked the beginning of Callas’s slow decline, but the myth exploded; celebrity thrives on human roughness, pain and caprice, shame and humiliation—fragility. Angelina Jolie studied this aspect.

Elsa Maxwell and Maria Callas—Love and Jealousy

Elsa Maxwell was in love with Maria Callas. A writer and journalist, Maxwell, with her connections and her desire to entertain, amuse, and organize parties, had made the Lido of Venice a stop in the leisurely wanderings of high society in the 1940s and 1950s—the Café Society that emerged after World War II and would soon be called the Jet Set. “The Hostess with the Mostes'”—that’s how Irving Berlin referred to Maxwell in a song, and so she remained famous.

A lesbian never hidden but never declared, she fell in love with Callas when Callas was married to Meneghini, perhaps truly without ever sharing a bed. Some say it was Maxwell who introduced Callas to Onassis—but this doesn’t happen in Larraín’s biopic. Maxwell quarreled with Callas and distanced herself when the relationship with the shipowner became anything but platonic, and jealousy couldn’t bear it. Maxwell would soon also quarrel with Wallis Simpson, Duchess of Windsor—but that’s another story.

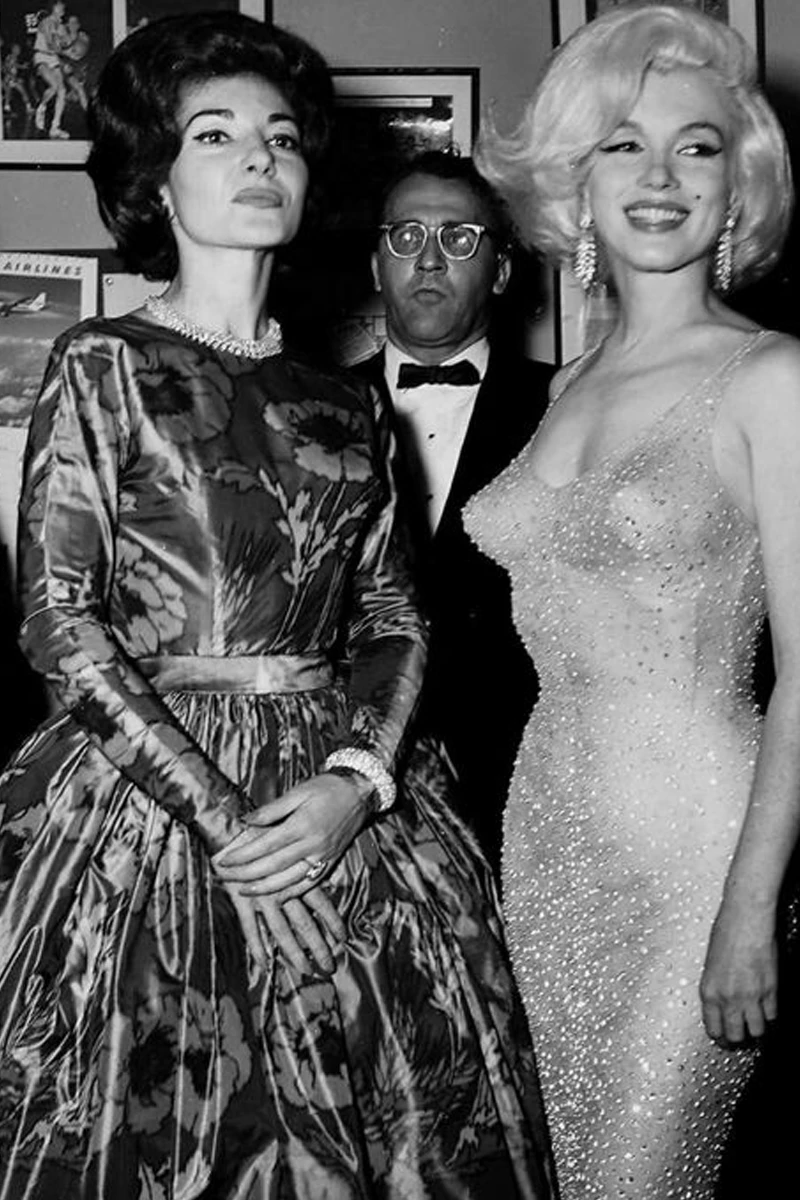

Pablo Larraín: In a Scene from Maria, the Meeting Between Callas and John Kennedy

In Pablo Larraín’s biopic, there’s a scene of a meeting that may not have happened in reality—when John Kennedy sits at a table with Maria, alone because the guards have moved others away. Shortly before, Marilyn Monroe had sung “Happy Birthday” to the president, with whom she presumably continued the festivities in the intimacy of a bed, indulging in voluptuousness. Now, perhaps it’s the next morning; Kennedy sits composed across from Maria. Maria asks him where Jackie might have been that very night and doesn’t hide her annoyance: she accuses him of having abandoned a wife who went to console herself with the only man Callas wanted for herself. Callas stands up and leaves Kennedy equally annoyed. We, the audience, are left with the roughness of Callas that Jolie has so adeptly portrayed.

Onassis detested opera; he wasn’t interested in music. Maria Callas discovered Onassis and Jackie’s marriage from a news broadcast. Over the years, Callas’s voice weakened. Love for Onassis had begun the distraction. Dedication to art and her legend had cracked; the fracture would become irreparable. The fault was nostalgia, which reacted with her character—the irrationality, the rough pride of a woman who could do everything with her vocal cords but was defeated. Memories burned her neural pathways. In Monte Carlo, Callas was not received at the palace because she was the concubine of a shipowner whose excessive wealth was annoying to the sovereigns of a small strip of land by the sea—yet the concubine overshadowed Princess Grace, because in those years, the true queen of Europe was only Maria Callas. Decline is the story of this film.

Carlo Mazzoni