New York City civic power and urban planning: neighborhoods contested

From Elizabeth Street Garden to Willets Point, and through East Harlem, Port Morris, and East New York: urban transformations in New York’s neighborhoods

Data and tools: the measured city and the risks of abstract planning

According to the Urban Displacement Project, more than 30% of New York City census tracts are at high risk of displacement. Around 90% of public housing is located in low-income areas, but only 21% is found in areas undergoing transformation. In addition, digital redlining—digital exclusion based on geographic and ethnic criteria—continues to affect neighborhoods with predominantly Black and Latinx populations.

While public initiatives have produced tens of thousands of affordable units, civic participation remains limited. Public hearings rarely result in substantial changes to proposed plans. Data reveals a continuous erosion of local identity and shared gathering spaces. The quantitative dimension—rents, zoning, square footage, investment flows—often displaces meaningful political debate.

Where We Live NYC and Local Law 78: towards equitable urban planning?

The Where We Live NYC program, launched in 2020 and updated in 2025, is an initiative from the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD). It aims to counter housing discrimination and spatial segregation through regulatory, urbanistic, and social planning tools. The plan includes measures to expand affordable housing supply, prevent evictions, improve legal access to housing, and collect disaggregated data to support equitable development.

In parallel, Local Law 78 requires developers to include Racial Equity Reports in their urban proposals, analyzing how new projects will impact various ethnic communities. The Equitable Development Data Explorer is a public platform that allows citizens, researchers, and decision-makers to access data on race, income, housing composition, and risk of displacement in each neighborhood.

But the implementation of these tools raises crucial questions: how much influence do they really have over final decisions? Who enforces their recommendations?

Elizabeth Street Garden: the politics of open space in urban redevelopment

In Nolita, the Elizabeth Street Garden stands as a revealing case. A non-commercial green space of about 4,000 square meters, opened in the 1990s on city-owned land, it has become a hub for collective initiatives, school programs, and neighborhood events.

In 2012, a proposal emerged to redevelop the garden into a complex of 123 housing units for low-income seniors, as part of the Housing New York plan. What followed was a decade-long political and legal battle among residents, advocacy groups, developers, and city authorities. In 2025, a compromise was reached: the garden will be preserved, while the housing project will be relocated across three sites in Soho and Chinatown, totaling more than 620 units.

The new solution requires a separate rezoning process for each site, increasing costs and inter-district coordination challenges. Green space becomes a bargaining chip, and Elizabeth Street Garden a symbol of how urban planning decisions reflect power dynamics more than shared priorities.

East Harlem: civic participation and top-down decision-making

East Harlem, a historically Puerto Rican and Latinx neighborhood, is one of the most debated cases of partial urban reform. Since 2016, it has been subject to a contested municipal rezoning plan. Local communities proposed an alternative: the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan. Despite years of participatory work, the plan was only partially adopted. New commercial developments have steadily replaced historic storefronts, while rents continue to rise.

According to the NYU Furman Center, East Harlem experienced one of the sharpest increases in rent between 2010 and 2023. Along Lexington Avenue, new buildings clash visually and socially with the remaining low-rise housing. Public buildings sit vacant, held in speculative limbo.

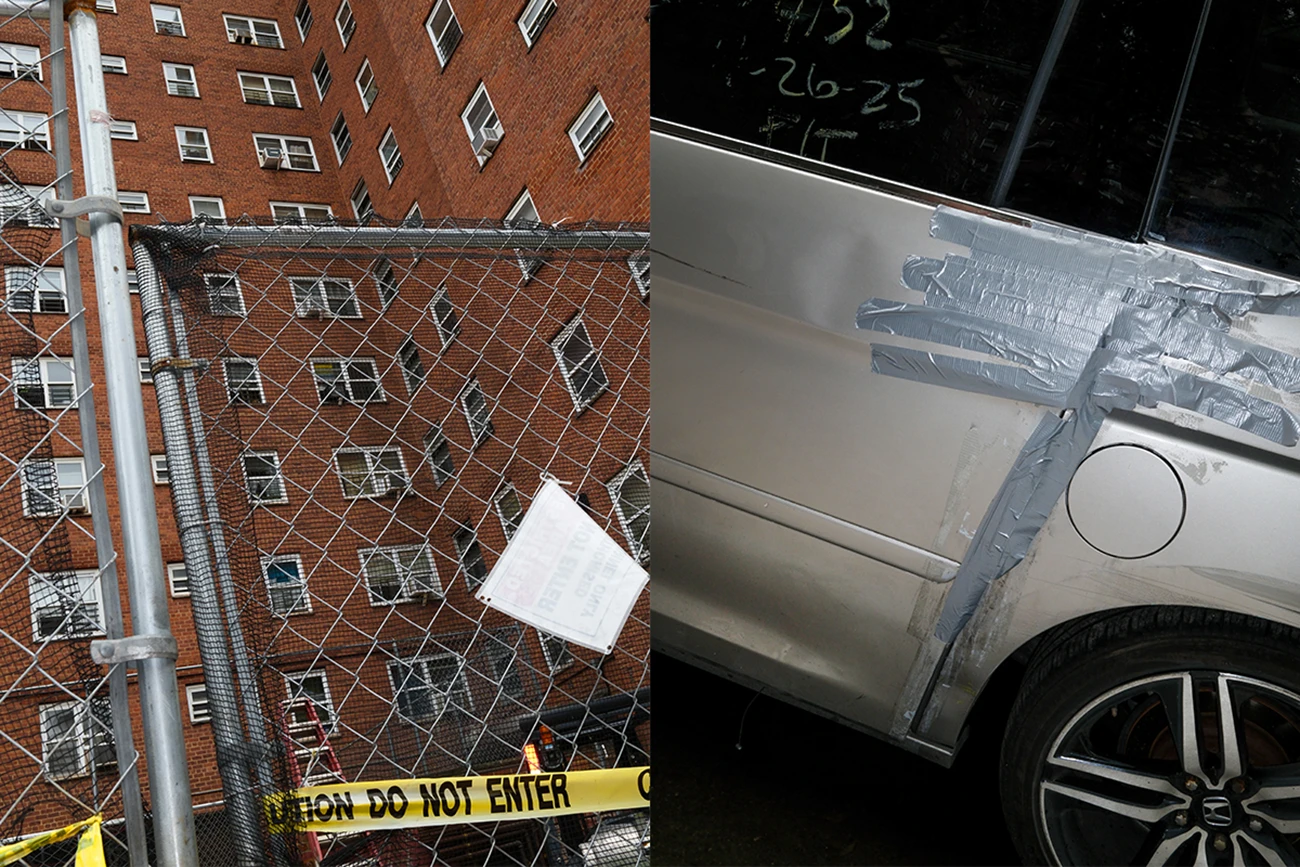

Civic participation clashed with institutional rigidity. The result is a suspended urban landscape—one where displacement happens in slow motion, hollowing out before rebuilding.

Port Morris: Community Land Trusts and civic reclaiming of urban space

In Port Morris, Bronx—an industrial area undergoing transformation—tensions are equally present. Between 2020 and 2024, rents rose by over 20%, while the median household income remains around $38,000—roughly half the city average.

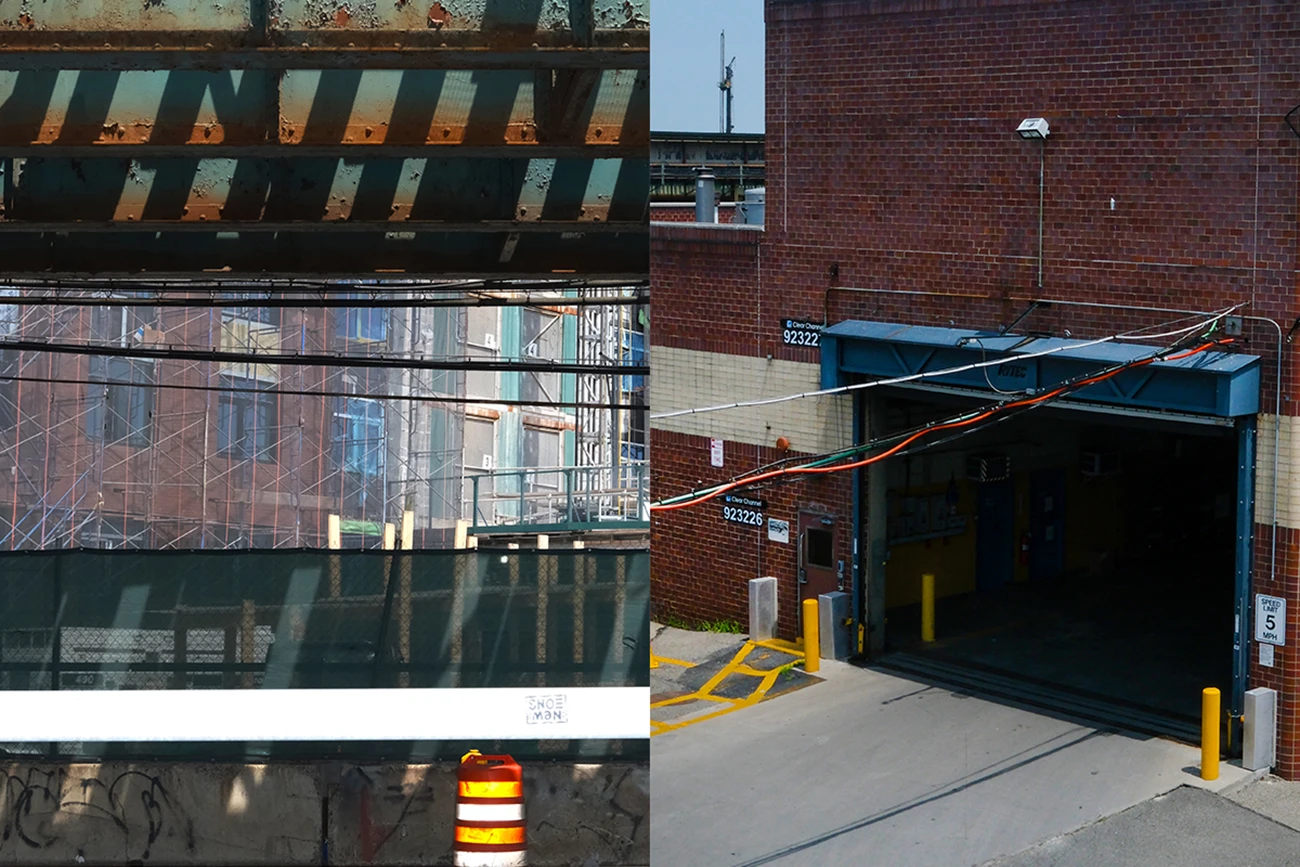

The area has seen mixed-use redevelopment: the conversion of warehouses like the Estey Piano Factory’s Clock Tower, and the emergence of creative spaces such as Silvercup North, a production studio opened in 2019. Yet environmental concerns persist: Port Morris sits in the so-called Asthma Alley, with childhood asthma rates exceeding 17%.

In response, civic action has taken root. South Bronx Unite installed 65 environmental sensors and helped launch a Community Land Trust managing a public building under a 45-year agreement. This stands as a rare case where community activism translates into concrete tools for managing urban space.

East New York: flexible zoning and the erosion of social cohesion

In Brooklyn’s District 5, East New York is the site of the Innovative Urban Village (IUV) program. Since 2022, over 450 new housing units and public spaces have been introduced. About 15% of the new housing is reserved for people experiencing homelessness. The project adopts principles from the City of Yes initiative, with flexible zoning mechanisms and over $260 million in public funding.

Despite green design, solar panels, and rooftop gardens, East New York remains classified as high-risk for displacement. Rents have risen 20% in four years—compared to a 12% citywide average. Black and Latinx communities report the disappearance of cultural landmarks such as independent churches and social clubs.

Five public hearings were held, but residents say they had little impact. The 2024 documentary East NY Voices gathers testimonies: “The plan brings services but scrapes away the soul of the neighborhood.”

Willets Point: large-scale redevelopment and the disappearance of working-class identity

Willets Point in Queens represents the other extreme: a fully orchestrated public-private redevelopment project. Once a marginal area of auto shops and scrapyards, lacking basic infrastructure, it is now home to Etihad Park—a 2,500-unit affordable housing project with a 25,000-seat stadium, schools, green space, and retail.

Phase one includes 880 regulated units; the second will add 1,200 more, alongside a school and the sports complex. The Independent Budget Office estimates the public cost—through tax incentives and exemptions—exceeds $1 billion. The cleanup began in 2021, involving soil decontamination and utility reconnection. Dozens of businesses were evicted.

Willets Point today is a contradictory construction site: cranes, solar panels, fences, and unremoved shacks. Its working-class identity has been erased. The project, while ambitious, exemplifies an urban planning model unanchored to local histories.

Building a fair city requires more than better tools—it requires real democracy

Across these case studies, a recurring theme emerges. Planning tools, no matter how refined, fall short when communities are excluded from actual decision-making. Planning is not neutral—it allocates resources, determines visibility, and enforces silence.

The reshaping of New York is also a reshaping of who gets to live, stay, and belong in the city. True transformation demands not only policy innovation but a redistribution of power: who decides New York?