Nosferatu: Robert Eggers’ Love Letter to Black Magic

Frankenstein, Dracula, and the New Nosferatu with Bill Skarsgård and Willem Dafoe: The Year Without a Summer of 1816 Inspired Gothic Literature’s Monsters and Influenced Robert Eggers’ Horror and Cinema

1816: The Year Without a Summer

1816 is also known as The Year Without a Summer. Chronicles from the time describe it as a disastrous year, primarily due to several large-scale volcanic eruptions in Indonesia. The clouds of debris and ash ejected into the atmosphere acted as a shield against solar rays, causing a drastic drop in temperatures—up to one and a half degrees below average—across the Northern Hemisphere.

Villa Diodati and the Genesis of Frankenstein and Vampyre

In June of that rainy and cold year, by a seemingly peculiar coincidence, some of the most famous and esteemed Romantic poets and writers of the era were vacationing by Lake Geneva in Switzerland. Lord Byron and his young personal physician, William Polidori, resided at Villa Diodati, a luxurious mansion in the village of Cologny. Nearby, Percy Bysshe Shelley and his future wife Mary Godwin (then an eighteen-year-old, later known as Mary Shelley) were renting the more modest Maison Chapuis.

The days were all the same: cold and rainy. Thus, in the boredom of an unbearable summer and in search of some strong emotion, the group of vacationers, after forming friendships, decided to spend time together reading ghost stories, primarily from German literature. All this was under the intoxicating effect of abundant doses of laudanum, that is, opium tincture in alcohol. A writing contest was also announced for the evening of June 17th. The rule was simple: the winner would be whoever wrote the best ghost story.

Only two stories garnered the most success among those present. Mary Shelley drafted a first version of what would become Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. Polidori, Lord Byron’s physician, wrote The Vampyre, inspired both by some tales and by Byron himself: a decadent dandy with narcissistic and overtly manipulative traits (so much so that Byron would publish the story under his own name, only crediting Polidori later).

From the Myth of Dracula to Pop Culture

That evening of the Year Without a Summer gave shape to two of the quintessential monsters of Gothic literature and modern horror imagery: Frankenstein, the morbid experiment that brings a collage of corpses to life with its own consciousness, and especially the vampire as we know it—a demonic presence that feeds on innocent blood to satisfy its thirst for undeath.

While Frankenstein has periodically enjoyed significant revivals, it is the vampire, particularly in Bram Stoker’s 1897 version of Count Dracula, that has maintained a constant, omnipresent presence in popular culture, first in the West and then globally. Leveraging attractive elements like immortality and repulsive ones like the fear of evil demons masquerading as humans, the vampire genre has never seen a decline. In fact, its reinterpretations are countless, even when narrowing the focus to Dracula and cinema alone.

Nosferatu According to Robert Eggers: An Obsession Realized

Starting with that 1922 Nosferatu, which concluded with a plagiarism lawsuit filed by Bram Stoker’s heirs (the film survived to this day only because director Murnau was ordered to destroy all copies, but one was secretly preserved), the Dracula story has been told in a thousand ways and is known practically by anyone born between 1897 and 2010.

This leads to the critical question: what could Robert Eggers, with his Nosferatu releasing on the first day of 2025, say that hasn’t already been addressed in past renditions of the Nosferatu/Dracula story? How can one scare in 2025 by leveraging characters that, even cinematically, have surpassed a century in age? The director has always stated that his Nosferatu was a personal obsession, something that eventually had to be done. Announced back in 2015, it was supposed to be the second film in his brief but notable filmography. Instead, it was postponed multiple times for various reasons, perhaps due to a legitimate fear of failure? The fact is, he finally filmed it, now able to rely on the resources, budget, and all production means of an established and universally acclaimed director. This certainly helped.

Vampire and Occultism: the New Face of Orlok

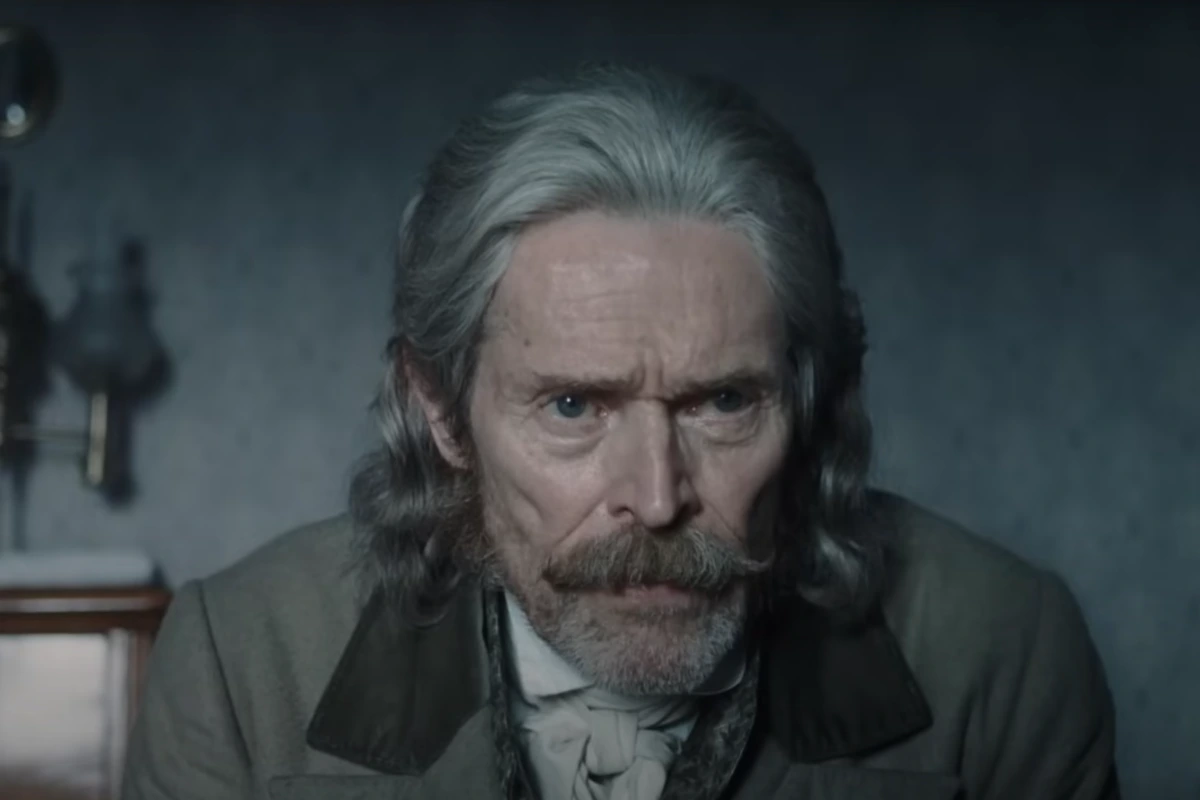

The star-studded cast, featuring names with whom the American director had already collaborated successfully (Willem Dafoe in The Lighthouse) and significant debuts as protagonists like Lily-Rose Depp (a gamble, in my opinion, that paid off), the sublime photography by Jarin Blaschke (now Eggers’ right-hand since his 2015 debut with The Witch), with some scenes—such as those shot in candlelit inns—so dark that you might suspect Eggers has dabbled in being the Kubrick of Barry Lyndon, a feature film set in the 1700s and famously shot solely with natural light. Additionally, the meticulous study of costumes and sets to faithfully recreate early 19th-century Romania and Germany: these are all crucial elements that added tremendous value to the work. But these things alone did not answer our initial question.

Something innovative was necessary, especially to present scenes from a plot that we already know very well from a different perspective. The narrative had to be not radically, but drastically rethought, even if it meant taking apocryphal liberties that go beyond Bram Stoker’s sacred texts. Well, Eggers did all this and more.

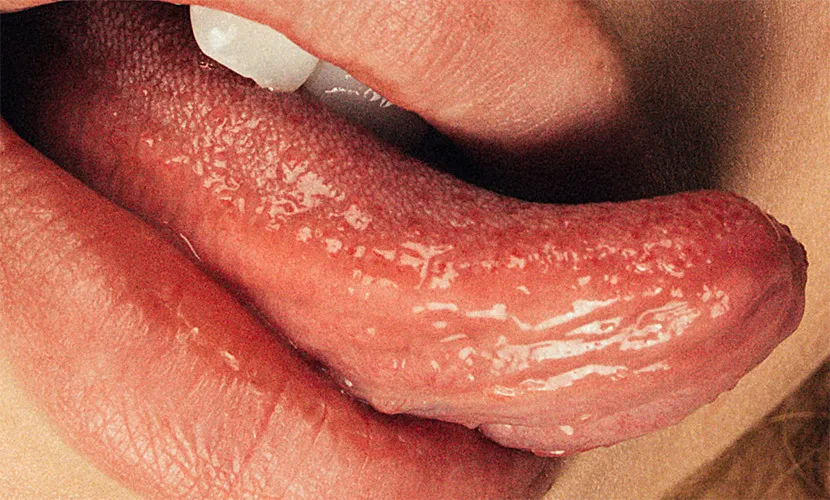

Dracula Introduces Sexual Promiscuity into 19th-Century England

The character of Hellen Hutter (Depp), modeled after Stoker’s Mina Harker—a classic damsel, defenseless and helpless against a dark demon—becomes a central figure, with an active role rather than a passive one as the Victorian-era imagination of the story dictates. However, the story already disrupted norms at the time by also giving a masculine figure, Jonathan Harker, a passively homoerotic role, also helpless against the jaws of his dark lord. It should not be forgotten that Dracula’s importance also lies in the pioneering sexual promiscuity it introduces into 19th-century England, where both male and female vampires share the same prey in an embrace of flesh and blood that always exudes sexual tension during the act. Between Bram Stoker and Oscar Wilde, a close friendship is documented, and it is likely that Stoker himself was gay. The drafting of Dracula itself began a month after Wilde’s incarceration for homosexuality.

What Eggers Infuses in Bill Skarsgård for the Role of the Evil Count Orlok

Essentially (quoting directly from an interview with the actor), “interpret a dead sorcerer.” Nosferatu shifts the ontological supernatural aspect of the vampire into the more specific realm of the occult, alchemical arts, and cabalistic practices, rather than justifying vampires’ existence with the usual half-explained legends. It is clear that Eggers, like all his fans (including myself), is primarily attracted to the dark side of magic, grimoires, and the rituals of demon evocation from who-knows-which extraplanar dimension. At this point, it is not far-fetched to say that Eggers’ most congenial habitat, aside from the costume film setting, is precisely black magic.

In this sense, Dafoe’s character is perfect: an illustrious doctor now repudiated by academic circles due to his obsession with alchemy and the occult arts. He is a blend between Stoker’s Van Helsing, from whom he retains a comedic flair, and a sorcerer who lives in a dark, dusty house filled with ancient tomes from floor to ceiling. It is he who, at one point, to prove the vampire’s real existence, lashes out against the positivistic view of the world, which, according to him, has nullified all forms of mysticism and the ability to see beyond mere empirical scientific methods. These words somehow reminded me of Mace’s comments a few months ago regarding the discourse on spirituality in the modern world.

The Importance of Absence: A Flaw Among Shadows

Nosferatu is a good film. If we must find a flaw (and it is our task to do so), which in reality the various trailers hid very well, it is the physical and visual presence of Orlok. What had struck and evoked fear in the film’s early teasers was precisely the fact that the vampire’s face was never seen—only an eerie, dark black silhouette immersed in the fog. Orlok was a dark presence, a shadow that moved within shadows. Inevitably, I realize that putting myself in his shoes, Eggers had to give the vampire a face, a voice, a physical presence within the scene. He had to, we agree, but perhaps he showed him a bit too much as a decaying body and too little as a shadow, as an unknown entity, thus sacrificing a bit of terror in light of the golden rule of horror: when it comes to fear and suspense, nothing is more present than absence. Just like in a Year Without a Summer.