Rough Lampoon #30: The Identity of a Magazine for the Future of Publishing

From the double O of Lampoon to the identity of a Rough Magazine: in-depth journalism dedicated to culture, where culture means transparency for both sides of the scale—the dirty and the clean

The word Lampoon and the Double O

I came across the word Lampoon while reading a book by Orson Welles, which mentioned The Harvard Lampoon. I noted it down because I liked the sound of it—even though I never thought it would become the reason for all my work. The term is American, not British—in England, when people ask me what Lampoon means, they assume it’s something like a harpoon, a weapon used for hunting whales. In Italian, Lampoon could be translated as a sharp, ironic, biting, or even satirical publication. We could say a rough publication. Nearly ten years have passed since Lampoon was founded—this is the 30th issue—and only recently did I realize that Lampoon contains the legendary double O.

Like Google and Yahoo—and also Facebook, Yoox, and many others. In America, they talk about the double O syndrome when searching for the right name for a digital startup. It’s as if the double O guarantees success, luck, and the future. Perhaps because the two Os, when they touch, resemble the infinity symbol.

Publishing: Credibility and Identity Form Authority

To grow and regain its dominant role in other markets and industries, publishing must strengthen itself on two pillars: credibility and identity. Together, they form authority. The internet is a jungle where people express themselves without any filter or restraint; where offense, provocation, and hate are an arena spectacle, as if everyone is waiting to applaud scorn and infamy. In this jungle, publishing is an escape from anger, shouting, and annoyance

People often say that print endures while digital fades. A false cliché, and the opposite is true: print products are lost once they leave the distribution flow; they get damaged and end up in boxes; counters and tables are renewed with more recent editions.

A well-constructed online page, built according to SEO architecture and focused on a specific topic, will always be found by user traffic for questions it can at least partially answer.

Print Publishing, Digital Publishing – Analog Photography and Rough Writing

Digital publishing needs print publishing. A photographer who has made a name in the image industry—an industry born from the blend of culture, fashion, and market—will not agree to shoot for a commission that doesn’t include print publication. A professional photographer is motivated by the print publication because it involves typography that confirms both the financial investment and the involvement of other craftsmen—the art director, the graphic designer, and the photolithographer. Typography guarantees commission value and relevance. It’s the certainty we all seek when we use effort, passion, and intellect in our work: not casting pearls before swine.

The photographs we publish in Lampoon are lightly retouched: we balance the colors for the printing process but do not reduce the image imperfections. Whenever possible, we use an analog camera, work with film, and actively seek the grain of the film. In this case, the light impressions become the substance of our photography. Furthermore, at Lampoon, we aim for rough writing. No adjectives, no adverbs, no rhetoric, no flattery, no compliments.

Words like important are banned—there’s no need to warn that something may be important; it just needs to be demonstrated. If demonstrated properly, it doesn’t need to be said. Similarly, words like extraordinary, fundamental, and essential are not used—they apply to everything and nothing.

He, she, they—are objects, not subjects. A main clause doesn’t start with a conjunction. And so on. By adhering to these and other guidelines, writing becomes more comprehensible because it mirrors our logical thinking, making it cleaner and more streamlined. The reading flows more smoothly. Fluidity isn’t the opposite of rough, but otherwise complementary—because only fluid can embrace all the thorns and corners of our literary life.

Like all historic editorial offices, at every meeting, we gather editorial proposals. Before proceeding with a topic, it must meet five questions, five criteria. Why is it rough? Why is it sustainable? Why is it cultural? Why is it strong in SEO?—SEO understood as the architecture of a text, the verticality of this topic—and also for the current SEO trend. Finally, why does this topic work with the publisher’s network?

Publishing Authority and Luxury in the Common Imagination

Authority demands that we become well-prepared professionals on a specific subject. There is nothing more appropriate for human and entrepreneurial evolution. Lampoon is a magazine that will celebrate ten years of activity in 2025: ten years of journalism that evolved in the market, sometimes anticipating, sometimes following. In 2015, we introduced the concept of digital tribes and discussed how the luxury world of Prada and Valentino should become a popular topic for everyone—the title was Snob and Pop.

At that time, luxury was a niche conversation for a few affluent individuals. Those who could afford it wanted to buy what others only dared to dream of—but if others weren’t dreaming of luxury because they had no idea of it, then even those who could buy it no longer knew what luxury was. Generation X didn’t know what Galliano was designing at Dior. Today, we are at the opposite extreme: luxury has become so widespread and accessible in the common imagination that it has annihilated the sense of privilege that should satisfy those who can afford it. Today, middle schoolers want Dior backpacks.

Lampoon, a Magazine of In-Depth Coverage Focused on Culture

In ten years of in-depth journalism, Lampoon has covered many, too many, topics—which the technical verticality of SEO can no longer allow. Lampoon today is a magazine of in-depth coverage focused on culture. Lines, pages, and time for flipping through and reading. These are never the articles or services you would choose for easy or light entertainment. Pausing or lingering over complex, non-immediate reasoning requires concentration and, hopefully, open-mindedness.

This means playing with culture in a broad sense—in a narrow sense, today culture means sustainability; sustainability means respect. Culture is the art of respect. Today, in every industry or manufacturing sector, and in every production chain, from agri-food to textiles, from tourism to energy, there is nothing more expensive than sustainability. The only market that can afford sustainability over consumerism is the luxury market. We could settle for a bit of avant-garde experimentation for a marketing strategy—as long as we avoid the humiliation of greenwashing.

Definition of Greenwashing and the Only Antidote: Transparency

There is only one antidote to avoid greenwashing: transparency. In describing any operation positively, a company that guarantees transparency will reveal its compromises, inaccuracies, counterpoints. There are only a few companies that are prepared to do so. They are governed by managers, not owners—no manager would give the go-ahead to communicate any negative aspect of a strategy or activity: they would risk being held accountable.

As a manager, you set your employees to tell the positive side of the scale instead of the negative side—without realizing that the scale works on balance. The positive side is appreciated by the interlocutors only when they assess the opposite side. When companies only tell the good variables, operating under the illusion that people won’t guess the dirty side of that good, it’s called greenwashing. Exposing the dirt along with the effort for cleanliness means transparency. At Lampoon, we use the word transparency instead of the word sustainability.

Lampoon, a Rough Magazine – What Does Rough Mean?

In this context of transparency, Lampoon today seeks everything that can be rough. Lampoon, a Rough Magazine—what does rough mean?

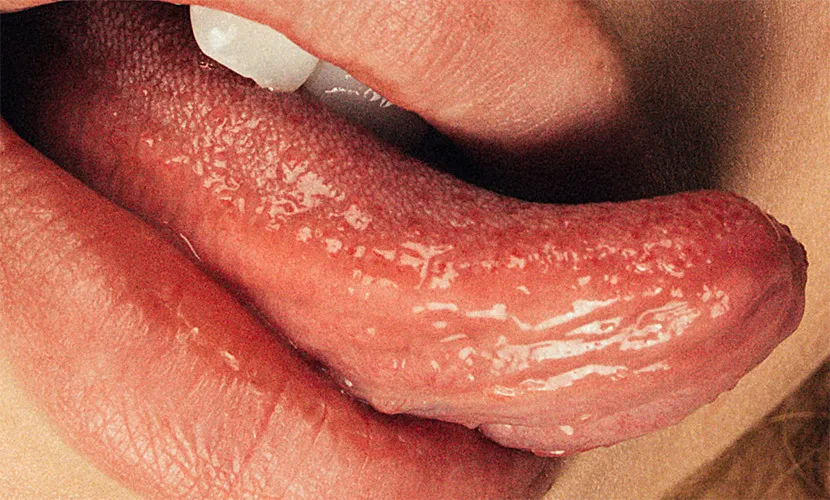

In nature, the earth is rough, the wood is rough. Nature in the wild, in our collective imagination, is rough—it appears untamed, resistant to domestication. So is love: we get entangled in the roughness of our characters, rub against each other, and touch between our hairs.

Lampoon has a single enemy against which we fight, curse, and rage. An enemy that is anything but rough, invented to appear smooth, perfect, sterile, and rounded without cracks and without roughness. Plastic.

The skin, the hair, the bruise, and the redness, the tired eyelid, the bitten nails, the anus, the roughness of the heel, the muscle’s volume before the armpit’s hollow, the flaw, the crease for the drop of sweat, the stale smell that you want to swallow.

What is Lampoon at the count of its 30th issue going to print? A rough magazine that talks about the power of fragility and the intimacy of a human body in all its most sincere grooves.

Rough is a surface that feels three-dimensional and abrasive to our touch. The surface contains textures, layers, reliefs, wedges, hollows, cracks, wrinkles, suggesting resistance to our passage.

Carlo Mazzoni