Royal Champagne: the Architecture of Balance in the Vineyards

Reopened in 2018 above Épernay, Royal Champagne Hotel & Spa occupies a former post house and operates with low-impact architecture, LED lighting, water-saving systems and extensive waste sorting

Royal Champagne Hotel Architecture in the Champagne Vineyards

There’s a moment, on the hills above Épernay, when you realize the building isn’t trying to compete with the landscape. It’s trying to disappear into it. The Royal Champagne Hotel & Spa stretches horizontally along the slope like an animal settling into its territory, low and wide, refusing to interrupt the vineyards that define this place.

This is no accident. When the five-star property reopened in 2018, occupying the site of a former post house, it did so with a clear understanding: in Champagne, the land comes first. Always. The hotel is the public-facing anchor of Champagne Hospitality’s collection, but it knows its place in the hierarchy. Architecture here doesn’t perform. It frames.

Royal Champagne Hotel & Spa: Architecture Embedded in the Landscape Above Épernay

The original stone structure remains intact, a nod to what came before. But the modern extension does something more interesting—it follows the natural contours of the hillside, built to capture uninterrupted views of the Champagne vineyards without announcing itself. Architecture and landscape operate as a single system here.

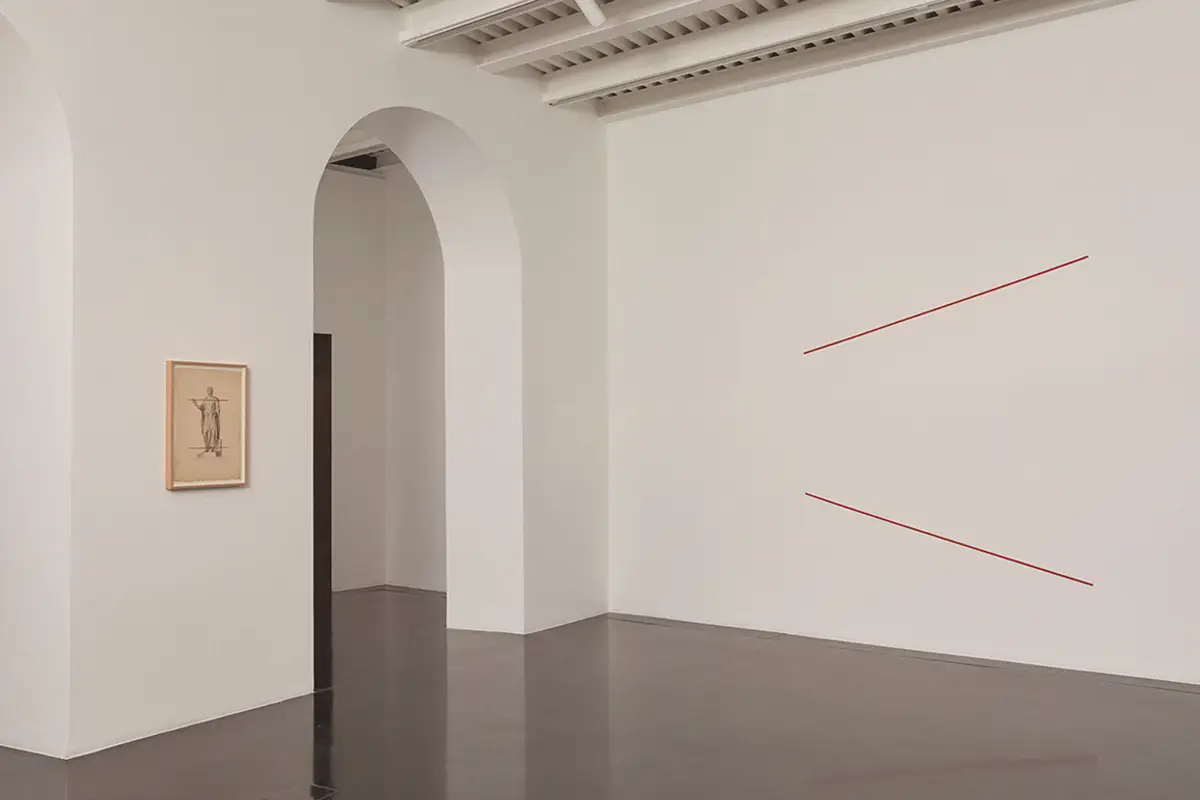

Broad openings, controlled volumes, an emphasis on natural light that orients the hotel outward, always toward the vines. Inside, the same logic applies. Materials stay restrained: mineral surfaces, muted tones, natural finishes used for continuity, not display. Restaurants, spa, shared spaces—all designed to function with precision rather than excess. Even in its most public areas, the hotel avoids spectacle. Design choices privilege proportion, material clarity and spatial calm. The setting remains dominant.

Royal Champagne Hotel Sustainability Systems and Environmental Design

At Royal Champagne, environmental responsibility isn’t an add-on. It’s the syntax through which the entire experience is built. The hotel operates within a regional ecosystem where sustainability is not a marketing theme but an operational condition, governed collectively by the Champagne appellation.

Energy and resource management starts with the basics. LED lighting throughout the property limits unnecessary consumption. Water use is controlled through low-flow fittings, regulated irrigation schedules and a reduced linen change cycle. Paper has been largely removed from the guest experience—check-in, documentation and information systems operate digitally by default.

But it’s in waste management that you see the obsession with detail. Sorting exceeds regulatory requirements, extending to materials often ignored in hospitality operations. Cigarette ends are collected, processed and chemically neutralized through a closed-loop system that converts filters into insulation materials. Cork caps are recovered and reintroduced into specialized recycling streams that fund medical research.

Food and beverage operations follow the same logic of reduction and proximity. Short supply chains are prioritized. An on-site aromatic garden feeds the kitchens. Bread and pastry production is calibrated daily to occupancy levels, with surplus redirected internally or repurposed through partnerships aimed at reducing food waste. Takeaway options exist intentionally as waste-reduction tools, paired with recyclable materials.

This isn’t environmental heroism. It’s operational logic in a region where viticulture, hospitality and environmental management are already interdependent. The hotel’s actions mirror this collective logic—incremental, measured, continuous.

Champagne Vineyards, Terroir Limits, and Regional Regulation

To understand Royal Champagne, you need to understand Champagne itself. This is a region that is narrow, controlled and difficult by design. Vineyards press into chalk slopes and tight valleys across the Montagne de Reims, the Vallée de la Marne and the Côte des Blancs. Land is fragmented across hundreds of villages and worked by thousands of growers rather than consolidated estates. Expansion is structurally impossible. What exists is measured, classified and maintained under constraint.

Geography functions as discipline. Chalk subsoil dominates—porous and reflective, regulating water and temperature while forcing vine roots deep underground. The climate sits at the northern edge of viable viticulture. Cold winters, unstable springs and modest sunlight make ripening uncertain. Champagne exists because of this tension. Its wines are built on acidity, restraint and delayed maturity rather than power or volume. Chardonnay, Meunier and Pinot Noir share the territory without hierarchy, shaped less by variety than by exposure, slope and soil.

Comité Champagne and the Governance of Champagne Wine Production

Production is distributed across more than sixteen thousand growers working within a tightly regulated appellation. This fragmentation defines Champagne’s character. No single actor controls the territory. Coordination replaces authorship.

The Comité Champagne functions as the region’s central organizing structure, aligning growers, houses and cooperatives under shared production rules, environmental commitments and long-term strategy. Its role is not symbolic. It maintains equilibrium in a region where scale exists only through collective agreement.

Champagne is a working territory before it is a destination. Viticulture comes first, logistics second, hospitality last. Hotels don’t overwrite the landscape. They insert themselves into it. To operate here is to accept limits, pace and permanence. The region doesn’t adapt quickly. It absorbs slowly.

Circular Economy in Champagne: Waste Recovery and By-Products

Material results matter. Bottle weight has been trimmed industry-wide, cutting thousands of tons of CO₂ emissions in production and transport. Plastic, glass, cork and even used oils are collected, treated and reincorporated into supply chains. Wine by-products become bioethanol, fertilizer, animal feed, grape seed oil. Vine shoots are shredded and returned to the soil. Roof timbers feed energy recovery systems.

Shared treatment facilities, aerated storage tanks and biological effluent processing normalize these practices across hundreds of producers. Nearly ten thousand tonnes of waste are managed this way annually. It’s invisible to the visitor but structural—a quiet infrastructure for a complex industry.

Climate Change in Champagne and Regional Adaptation Strategies

Champagne has warmed over the last thirty years, shifting from a very cool-fresh climate to cool-temperate. Growth is easier, but extreme weather events are increasing, threatening consistency and terroir. The industry is preparing with soil management, hedgerows, regional energy projects and local carbon storage. Offsets are considered alongside emissions reductions. Every lever is tested, debated and implemented collectively.

Adaptation is as much a technical exercise as a cultural one—the appellation’s long-term survival depends on it. Carbon assessments started here in 2003. Champagne was the first wine region in the world to quantify its footprint. They’re updated every five years. The goal is to anticipate, measure, reduce and offset. Wine, land and climate operate as a single system.

Biodynamic Viticulture in the Champagne Region

Biodynamic production remains a minority practice in Champagne, covering less than ten percent of the vineyards, yet its visibility is increasing with climate pressures. A growing number of growers and producers have adopted holistic farming methods that avoid synthetic inputs and emphasize soil health, plant resilience and ecosystem balance, especially in warmer years when acidity and sugar balance become harder to manage.

Estates like Leclerc Briant in Épernay have worked biodynamically for decades, and others in the Côte des Bar and Marne Valley report marked differences in structure and crop consistency from biodynamic parcels. These methods still cover a small fraction of the region’s vineyards, but they signal experimental adaptation alongside Champagne’s broader sustainability efforts.

Waste sorting, energy efficiency, water conservation, low-impact transport and locally sourced food all mirror the broader Champagne ecosystem. The hotel is not a guest or observer of this process. It inherits the regional framework and translates it into hospitality—a measured extension of the same structural responsibility that sustains the vineyards.

Villa des Trois Clochers by Royal Champagne: Private Vineyard Residence

Among the vineyards of Villers-Allerand, there’s a different kind of silence. Villa des Trois Clochers occupies a quiet position as Royal Champagne’s sister property, recently restored and operating as a private residence with full hotel services. It’s part of the same Champagne Hospitality portfolio, sharing operational structure, staffing standards and hospitality framework.

But where Royal Champagne is public-facing and panoramic, the villa remains inward, controlled and deliberately low-profile. It responds to a clear shift in luxury hospitality: privacy without withdrawal from service. It’s neither a hotel nor a private home. It’s a controlled hybrid for guests who want autonomy without managing logistics, discretion without isolation.

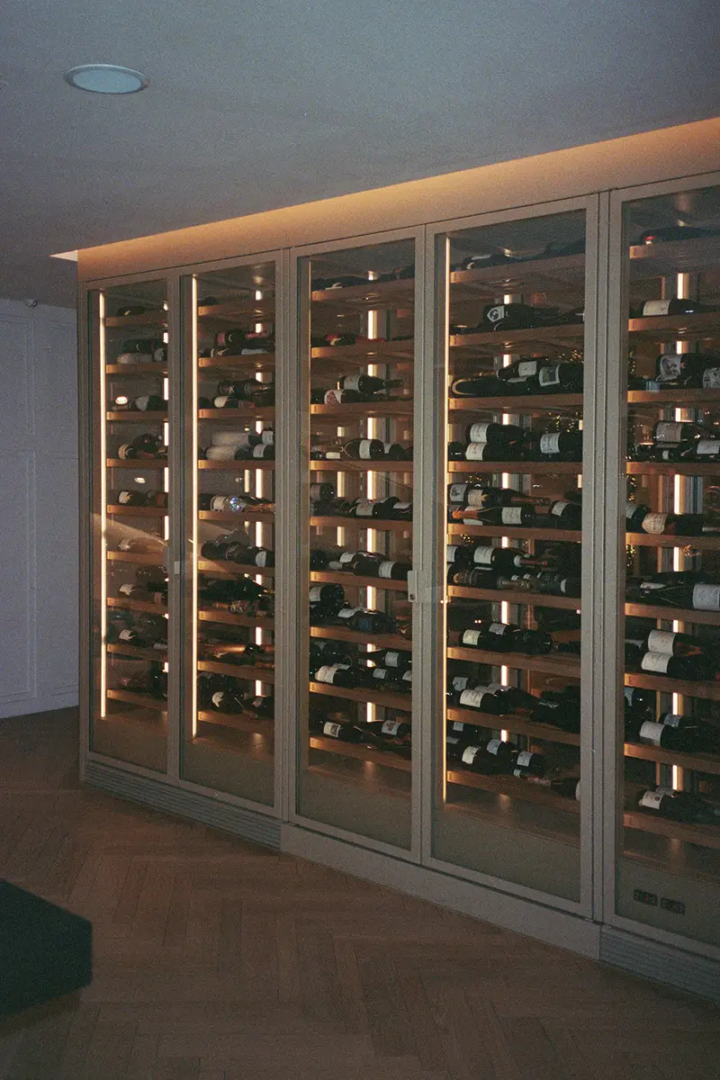

Butler-style service, in-villa dining by private chefs, curated Champagne tastings, vineyard picnics and cellar visits through neighbouring maisons are delivered with minimal visibility and no performative excess. The experience is residential in structure but hotel-managed in execution.

Villa des Trois Clochers: Art Déco Architecture and Interior Design

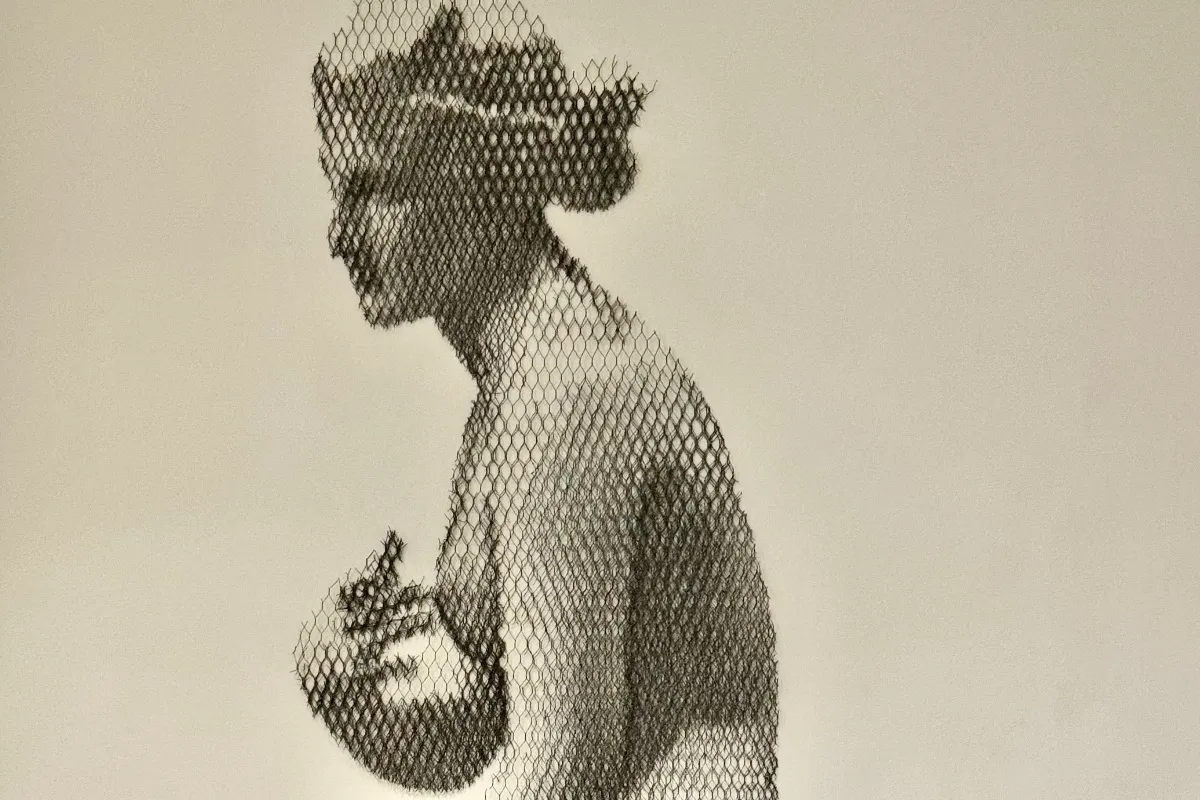

Architecturally, the residence retains its 1920s Art Déco structure. The restoration avoids decorative nostalgia. The interior palette is deliberately reduced, favoring mineral neutrals and muted vegetal tones. Smoothness is avoided in favor of material depth. Patterned wall surfaces, oak elements and small-format tiling introduce texture as a structuring device without creating decorative noise. The result is a space that retains character while allowing architecture and landscape to remain visually dominant.

The layout is organized around five large suites where scale matters more than turnover. The rhythm of the villa is intentionally unprogrammed: meals, tastings and leisure are arranged on request instead of a fixed schedule. Privacy and functionality become the currency of luxury.