Urban continuity and residential reuse at the former Teatro Comunale in Florence

From historic theater to serviced residential neighborhood, Starhotels Collezione anchors a broader urban regeneration project in the Corso Italia–Via Solferino block in Florence

Florence. The former Teatro Comunale returns to everyday life as Teatro Luxury Apartments

Florence does not give up on the places where it once found its sense of self. It brings them back into use. The story of the former Teatro Comunale fits this pattern closely. Built as a place of gathering, later left closed for years, the building has now re-entered the city’s daily rhythm. Within the block between Corso Italia and Via Solferino, Teatro Luxury Apartments Florence has opened: 156 serviced apartments operated by Starhotels Collezione. The intervention sets change in motion at the scale of the block, reopening permeability and restoring everyday presence to a nineteenth-century neighborhood.

Teatro Luxury Apartments: an urban rewrite in central Florence

Before it became the “Teatro Comunale,” this site was already home to a Theater. In 1862, the Politeama Vittorio Emanuele opened as a large arena designed for a Florence that was expanding in scale and ambition. During the years when Florence served as the capital of the Kingdom of Italy (1865–1871), the area between the railway station, the Arno embankments, and the newly built boulevards emerged as a strategic urban front. Construction intensified, connections were stitched back together, and the city was reshaped on a broader plan. This was the era of the Risanamento, led by architect Giuseppe Poggi.

The theater followed this process of layering and transformation. It was enclosed, modified, and gradually reshaped. In the twentieth century it became the historic home of the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, remaining for generations a cultural and spatial reference point. “Let’s meet at the Comunale” was a practical instruction before it carried any nostalgia.

When the theater closed, it left behind a void. A static block that cut pedestrian movement, eliminated pauses, and weakened street-level life. Corso Italia remained a traffic corridor; Via Solferino an unfinished seam. Today, short-to-mid-term living attempts to set this piece of the city back in motion. This is not another kitchenette-based accommodation. It is a fully serviced residential model, designed for stays lasting weeks or months, with shared amenities, on-site assistance, and common spaces. When it works, it generates repetition: grocery runs, coffee stops, routes, schedules. Urban regeneration begins with those routines.

The historic façade of Teatro Luxury Apartments Florence and the project by Vittorio Grassi Architects

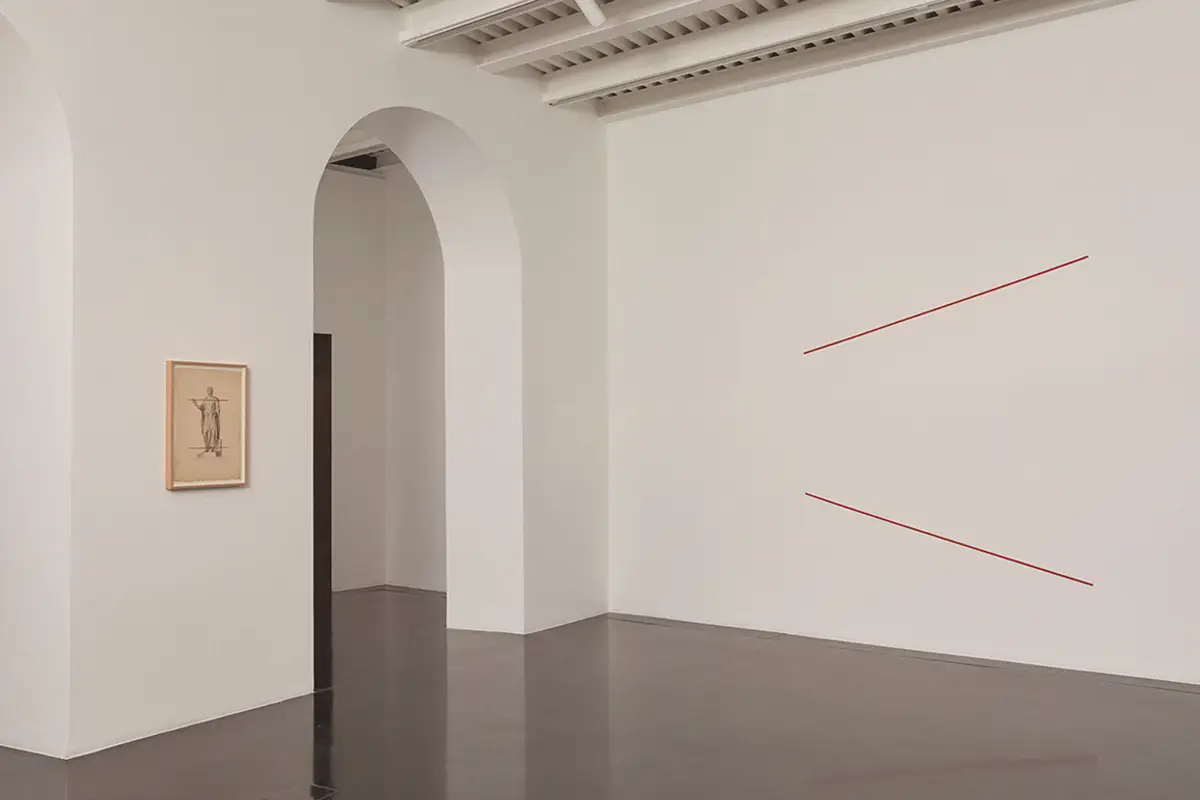

The theater’s legacy remains where Florence has read it for more than a century: along Corso Italia. The historic, protected façade has been preserved. No nostalgia. Its value lies in urban continuity: a recognizable frontage holds together before and after, preventing the street from losing a point of reference.

Behind it, the building changes. The theater was a single, compact body; residential use requires modules, multiple accesses, and long-term maintenance. The project—designed by Vittorio Grassi Architects—recomposes the block into several volumes and raises a question that is distinctly Florentine: how to transform without slipping into pure scenography.

Teatro Luxury Apartments Florence: 156 serviced apartments forming a residential micro-neighborhood in central Florence

One hundred and fifty-six apartments represent an urban threshold. Rather than a conventional condominium, the project functions as a residential micro-neighborhood with its own daily rhythms. The apartment mix ranges from studios of approximately 40–45 square meters to larger units. Each layout is organized around autonomy: a private kitchen, a defined living area, and space suitable for working. The presence of shared amenities shifts the focus from short overnight stays to longer periods of residence.

This aspect is relevant to Florence beyond promotional narratives. Time-based residential models generate continuous daily presence. They extend activity across the day and contribute to the activation of street-level uses.

Apartment layouts and residential typologies designed for short- and mid-term living in Florence

The units are conceived to support extended stays without replicating a hotel format. Storage, circulation, and domestic functions are designed to accommodate everyday routines. The apartments allow residents to establish regular habits rather than temporary occupancy patterns, reinforcing continuity within the surrounding urban fabric.

Material selection follows a functional logic rather than a decorative one. Living areas feature solid wood elements and oak parquet flooring, while doors are finished in Canaletto walnut. Kitchens and bathrooms use porcelain stoneware surfaces with a Calacatta Vagli Oro marble effect. In larger apartments, Saint Laurent black marble with gold veining is introduced to add visual depth without visual excess.

Some units include steam showers. Other design solutions address everyday use: retractable kitchens, pivoting panels that conceal television screens, and surfaces designed to limit visual clutter. Order is approached as a practical requirement before an aesthetic one.

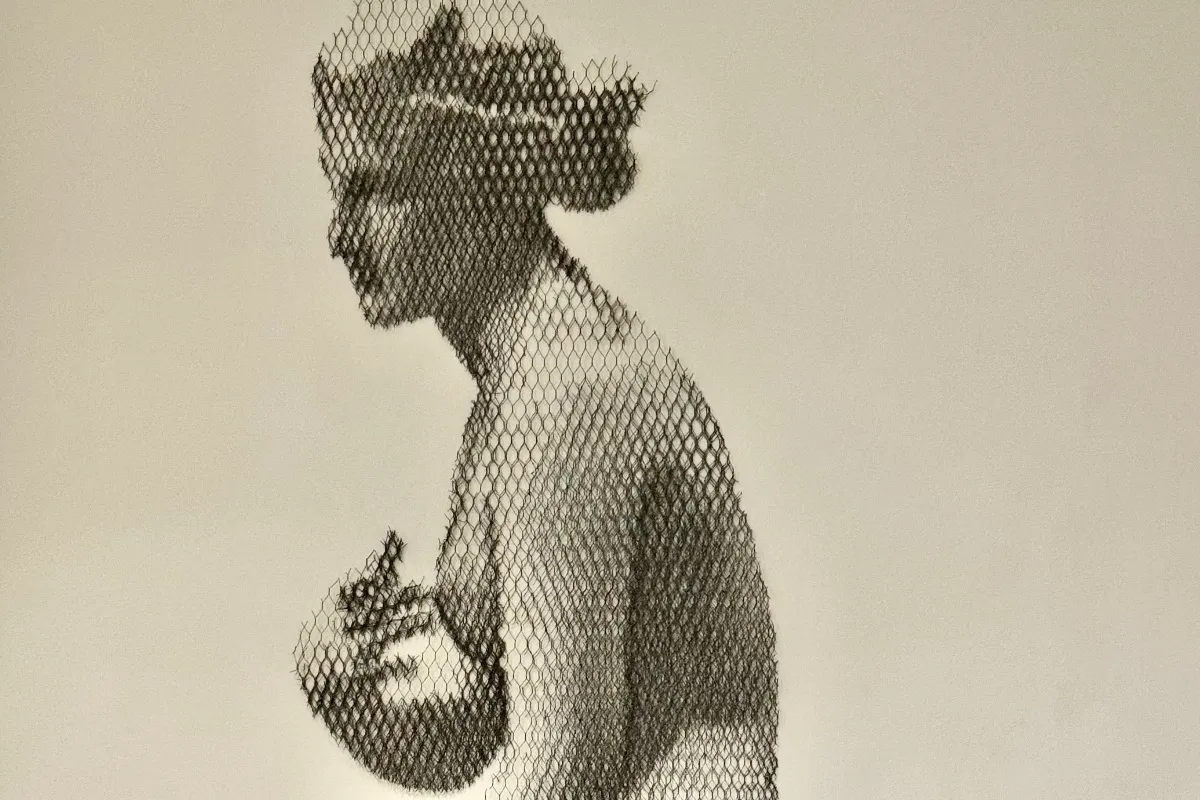

The relationship with the site’s theatrical history is expressed through measured references. Common areas include selected imagery and details drawn from Italian theaters and stage costumes. At ground level, a video installation by Felice Limosani presents sequences of performance, ranging from ballet to opera. These elements remain intentionally restrained, functioning as contextual references rather than immersive reconstructions. The former theater operates here as an archive integrated into everyday use.

Shared services, wellness facilities, and LEED Gold sustainability targets at Teatro Luxury Apartments Florence

The development includes food and beverage spaces, a wellness area with fitness facilities, and an underground parking structure. These services are critical in determining whether the internal square functions as an active public space or remains a transitional area. The project is pursuing LEED Gold certification, with sustainability addressed primarily through energy consumption control and long-term operational efficiency. Maintenance and durability over time are central to the project’s environmental strategy.

The functioning of the complex relies not only on architectural and landscape design but also on daily management. A dedicated on-site team provides continuous support to residents, ensuring operational consistency. This aspect is often underestimated, yet it plays a decisive role in determining whether a development operates merely as a well-designed structure or as a place capable of sustaining long-term use through ongoing care and management.

Piazza Maria Callas: a new point of orientation in Florence

The core of the urban intervention is Piazza Maria Callas. This is the decisive urban move, because it shifts attention from the building to the space between buildings. Here, the word “piazza” carries weight: it must function as a place, not a label. The idea is a permeable inner void, a place to pause, a node that connects residents and passersby.

The name is deliberate. Maria Callas’s connection to Florence is documented history. On November 30, 1948, she sang Norma at the Teatro Comunale. In January 1951, she returned as Violetta in La traviata. In 1952, she took on Armida at the Maggio Musicale. In May 1953, she appeared as Medea: three performances at the Comunale, conducted by Vittorio Gui. Florence encountered her at the moment when voice and repertoire aligned with roles that would become defining. Today, that name moves from theatrical record to toponym: meeting point, address, everyday orientation.

Around the square, three buildings carry names that act as a compass—Puccini, Rossini, Verdi. A legible system that keeps musical memory embedded in the city’s daily navigation.

Giuseppe Poggi’s urban framework: residential density, public space, and tree-lined infrastructure in Florence

The intervention is privately led, yet it directly affects public space. The redevelopment plan confirms a program that is 95 percent residential, with the remaining 5 percent allocated to services and office functions. It reduces the built volume compared to the former theater and ties the renewal of the block to the upgrading of its surroundings, beginning with the central parterre along Via Solferino. This is where the reference to Giuseppe Poggi becomes operational. During the years of Florence as capital, Poggi designed the tree-lined ring boulevards and a system of promenades that still structure the city today. Poggi is not a commemorative name; he represents a method based on shade, continuity, and clearly defined edges.

Along Via Solferino, this approach translates into concrete measures: rows of trees restored as a true boulevard, and a central parterre that moves beyond its role as a traffic divider to function again as a walkable public space. For Florence, this is a political decision before it is an aesthetic one. Green space is treated not as decoration, but as infrastructure.

Development structure and investment partners behind Teatro Luxury Apartments Florence

A project of this scale depends on a structured chain involving ownership, development, and management. The redevelopment is led by Hines and Blue Noble, with investment through the “Future Living” real estate fund managed by Savills Investment Management. Starhotels is responsible for operations. The distinction matters. Developers mobilize capital and long timelines; operators determine how that capital translates into daily presence, maintenance standards, and a working relationship with the surrounding neighborhood.

In a city where any intervention near the historic center generates debate, this structure also functions as transparency. It clarifies roles and responsibilities, allowing the outcome to be assessed on the ground rather than on declared intentions.

Via Solferino today: everyday routines and neighborhood services rather than destination imagery

Change becomes visible through daily habits. At Via Solferino 15–17, within the project’s perimeter, Ditta Artigianale has opened in recent weeks. It is the seventh Florence location of the roastery led by Francesco Sanapo, one of the early proponents of specialty coffee in Italy. The setting is direct: clean lines, industrial materials, a metropolitan tone. In an area that for years offered few reasons to stop, a café of this type operates both as a service and as an indicator of renewed activity.

Another opening is expected shortly: J Firenze, the city outpost of J Contemporary Japanese Restaurant, scheduled to open in mid-March. High-end dining tends to arrive when an area sustains evening activity and when a square can support consistent, non-episodic flows. It does not transform the city on its own, but it signals that the neighborhood has resumed functioning as a destination.