We Are Workers: Working-Class Heroes on Route 66

Through the raw lens of Rupert Tapper, explore a neighborhood that once marked the start of Route 66, capturing both the promise and disillusion of the American Dream

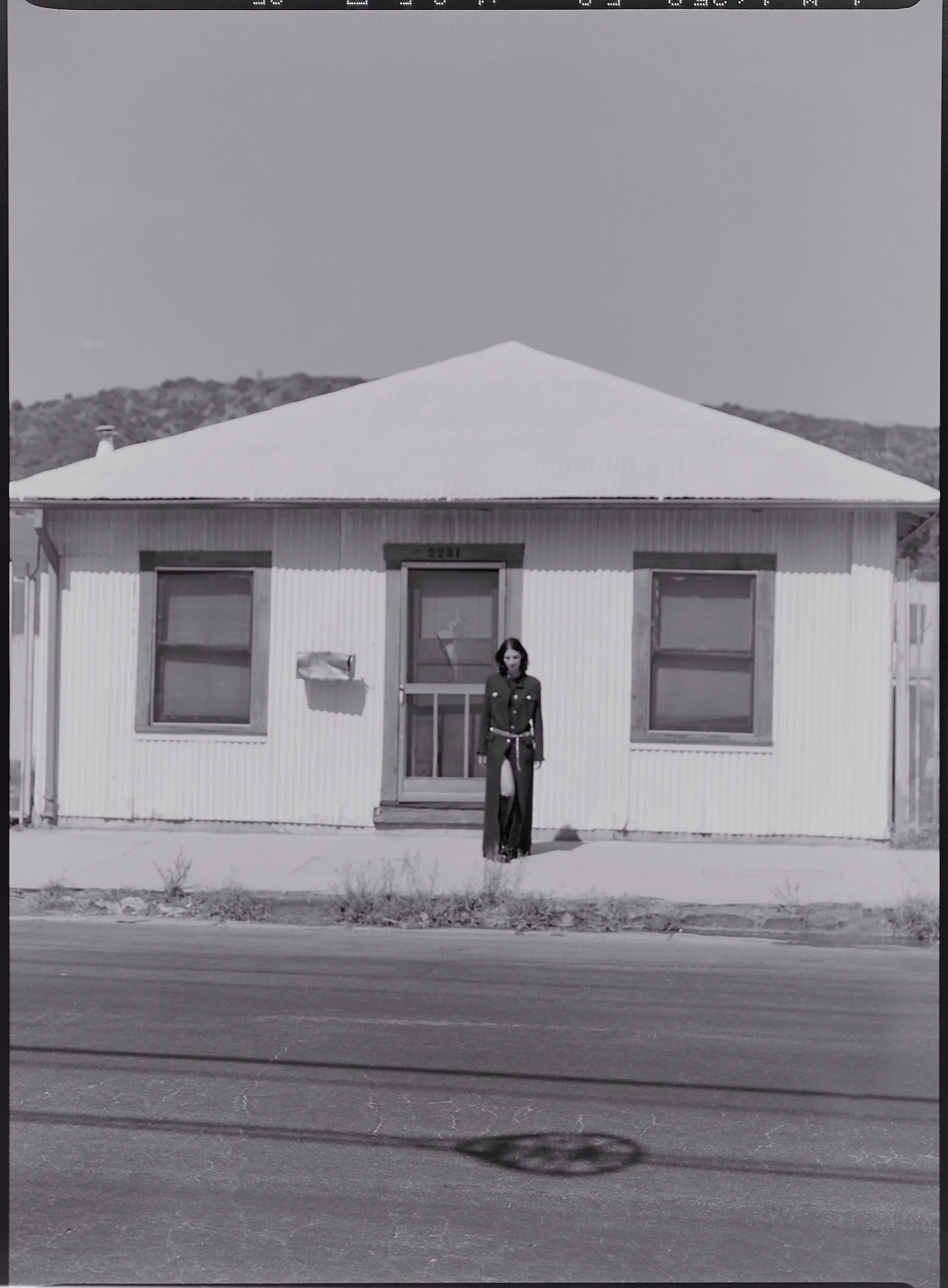

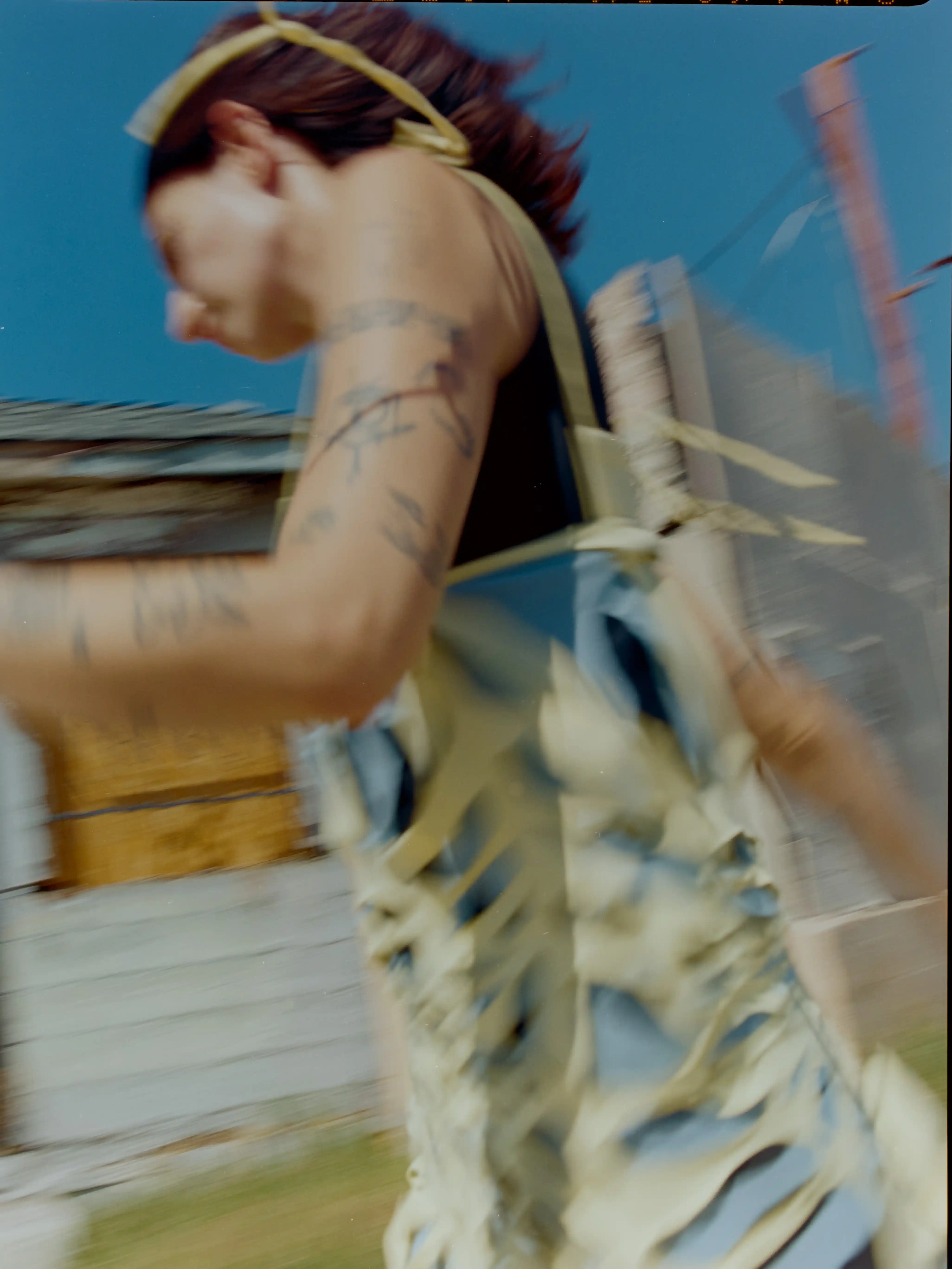

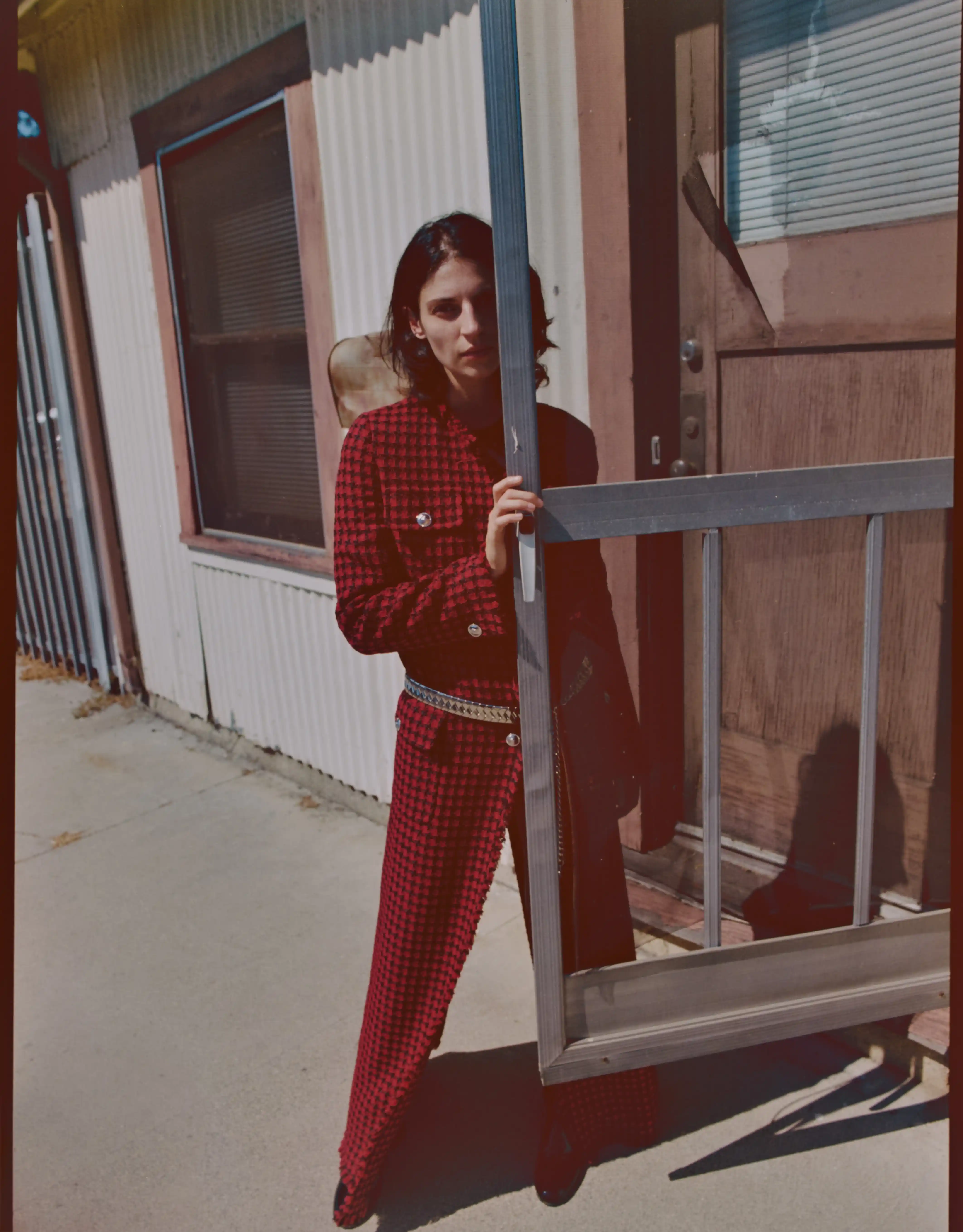

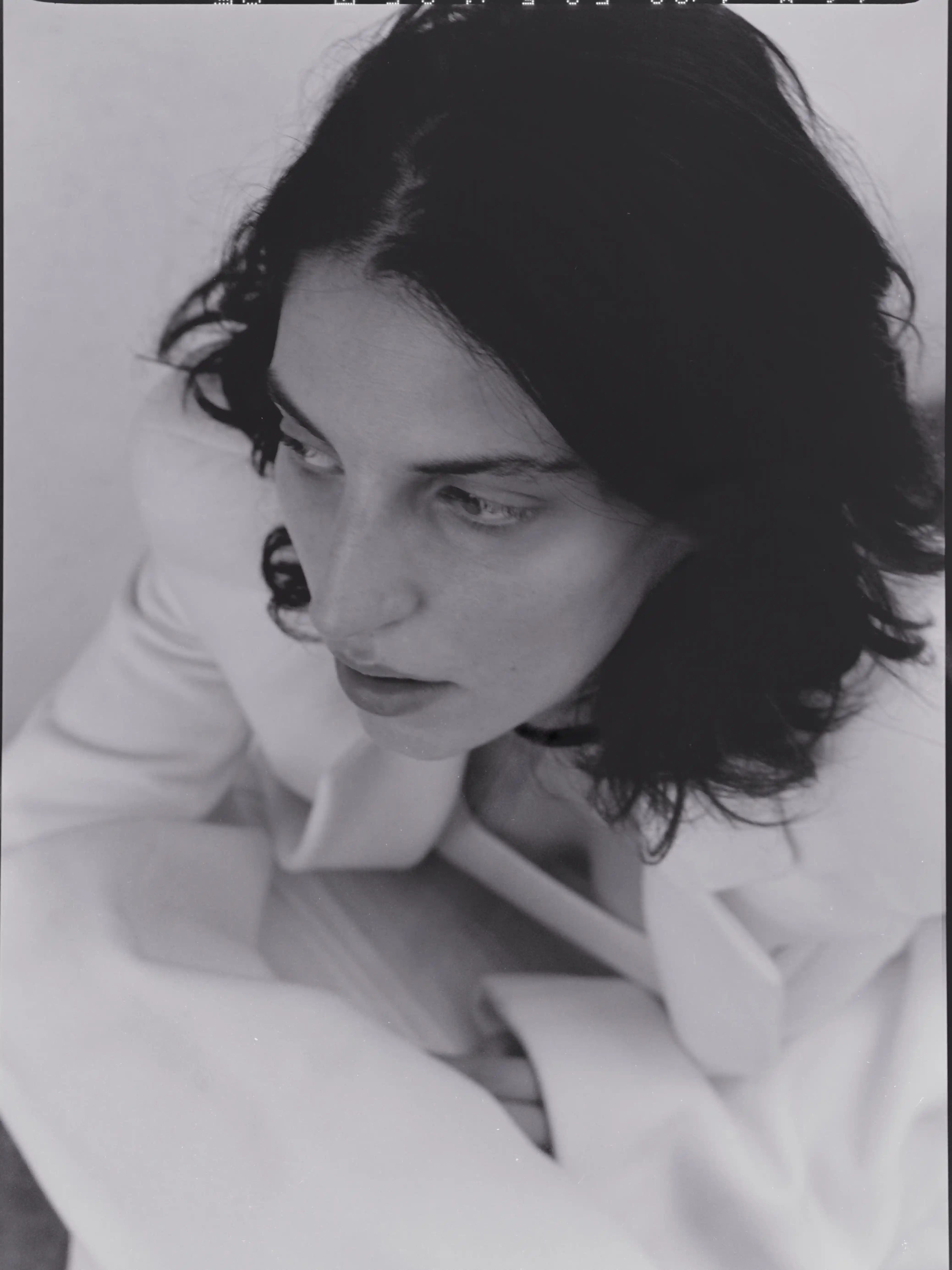

Rupert Tapper: “Take a walk through a neighborhood that once marked the beginning of Route 66, where only a faint echo of those booming years remains. Here, the desperation and devastation are palpable—a raw, stripped-down remnant of what was once the glittering promise of Tinsel Town. In this place, a woman seems to embody the struggle faced by so many who ventured west in search of a brighter future, only to end up waiting tables in a diner. This is Eagle Rock, and these are the working-class heroes.”

The history of Route 66

The story of Route 66 began well before 1926, the year when the United States Congress approved the creation of a network of highways connecting booming urban areas with more rural regions. In the early 20th century, American road infrastructure was fragmented and underdeveloped; traveling from one city to another often meant relying on dirt tracks, railroad routes, or stagecoach lines. With cars becoming more widespread, and the growing need for faster travel between towns and cities, the concept of a reliable, continuous highway became urgent.

It was Cyrus Avery, an entrepreneur from Oklahoma City, who played a decisive role in championing a highway that would link the Midwest with the American West. Aware of the economic potential that such a route could bring to Oklahoma and neighboring states, Avery convinced both federal and local stakeholders to rally behind a new project dubbed “U.S. Highway 66.” Originally proposed as “U.S. Highway 60,” political pressure and geographic priorities ultimately led to the change in numbering, thus cementing the “66” into history.

The Route 66 and Its Expansion

Stretching about 2,448 miles (nearly 3,940 kilometers), Route 66 began in Chicago, Illinois, and ended at the Santa Monica Pier in California. Along the way, it crossed a total of eight states: Illinois, Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. The diversity of landscapes was—and still is, wherever the original road survives—striking: from the farmlands of Illinois and the rolling hills of Missouri, to the wind-swept plains of Oklahoma, the rocky deserts and canyons of Arizona, and finally the sun-drenched beaches of Southern California.

Right from the start, this highway served as a powerful catalyst for economic development. Small and large businesses sprang up along its path, offering vital services to travelers. Gas stations, motels, diners, auto repair shops, and souvenir stores popped up in proximity to the route, quickly turning it into a “main street” for commerce and tourism. In the following years, the idea of a transcontinental highway captivated many Americans, luring them with promises of adventure and job opportunities in the expanding regions of the West.

The Golden Age of the Route 66: 1930s to 1950s

Route 66’s first major boom overlapped with the Great Depression of the 1930s. Ironically, economic hardship drove thousands of Americans westward in search of better prospects. The Mother Road became a symbol of hope for migrants—an escape route from the poverty afflicting the drought-stricken agricultural regions of the “Dust Bowl.” John Steinbeck’s famous novel, The Grapes of Wrath, vividly depicts the desperate journey of the Joad family from dusty Oklahoma to California—along what Steinbeck himself called the “Mother Road.”

During World War II, Route 66 maintained its strategic importance for the defense industry’s supply routes. But it was the postwar era that truly marked the road’s heyday. With the economic recovery, the baby boom, and the widespread availability of automobiles, countless travelers took to the highway—either for tourism or to relocate to new homes. Gas stations multiplied, and motels with bright neon signs lined the route, giving rise to a distinctly American iconography still associated with that era’s prosperity and carefree spirit.

Popular culture also fell under the spell of Route 66. Songs, films, and radio broadcasts celebrated the road’s singular quality and the sense of freedom it embodied. In 1946, composer Bobby Troup penned the now-classic “(Get Your Kicks on) Route 66,” a tune later covered by numerous artists and one that helped cement the highway’s reputation as a symbol of boundless adventure and opportunity.

Decline of the Route 66: The Interstate Highway and the End of an Era

Despite its romantic aura, Route 66 had its share of problems. Pieced together from existing roads and progressively upgraded over time, it was sometimes poorly maintained or ill-suited for the rising volume of automobile traffic. Its curves and slopes, acceptable in the 1920s and ’30s, no longer met the safety standards of the postwar period. Consequently, by the mid-1950s, discussions were underway to modernize the entire U.S. highway system.

The answer came in the form of the Interstate Highway System, officially launched by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1956. This plan aimed to create a complex network of multi-lane freeways, providing fast, safe connections between the nation’s major urban and industrial hubs. In the following decades, these modern roads gradually replaced the “old” U.S. 66, relegating it to the background.

As sections of Route 66 were superseded by interstates like I-40, I-55, I-44, and I-15, many local communities along the Mother Road lost their primary source of income. Motels, diners, auto shops, and stores closed their doors, leaving behind faded signs and empty parking lots. The road’s mystique, however, endured in the public imagination—fueled by nostalgia and curiosity.

Finally, in 1985, Route 66 was officially decommissioned from the federal highway system. This marked its administrative demise but did not spell the end of its legend.

A Revival and Enduring Allure

With the highway removed from official signage, Route 66 seemed destined for a lonely existence—little more than a wistful memory. Yet this “outsider” status sparked renewed interest, largely thanks to local initiatives and nonprofit organizations dedicated to preserving its history and cultural significance. By the late 1980s, various associations—such as the Historic Route 66 Association—were mapping out still-drivable original segments, restoring vintage-style buildings, and raising awareness about the road’s unique heritage and tourism potential.

Today, travelers from around the globe come to drive portions of Route 66, eager to relive a slice of American history while taking in the dramatically shifting scenery from state to state. “Nostalgic tourism” has breathed fresh life into communities along the corridor. Many have organized to offer visitors a chance to step back in time: you’ll find 1950s-style diners, carefully refurbished service stations, and small museums devoted to local lore. All of this makes a trip along Route 66 more than just another road trip—it becomes an immersive journey into the past.

Matteo Mammoli