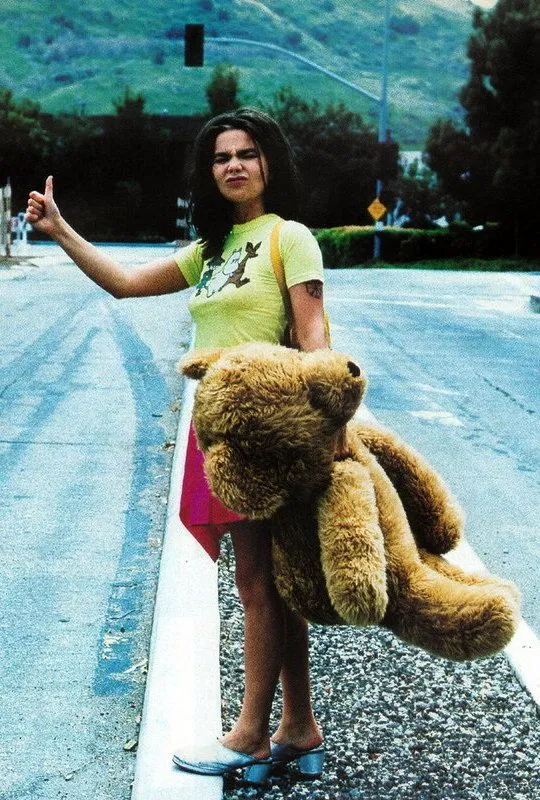

90s revisited: nostalgia for dirt, desire, and irreverent fornication

Why 1990s and Early 2000s Nostalgia Still Shapes Fashion and Culture? The decade that promised endless growth, liberal optimism, and global stability has become the default reference point for the present days

Why the 1990s and early 2000s are remembered as the last happy moment of stability

The culture of the 90s emerged from exhaustion: a deliberate recoil from the Cold War, corporate power and moralized excess that had defined the previous decade. 90s and early 2000s were radically different. A time that now reads as the last happy moment.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, liberal democracy was framed as the endpoint of ideological conflict. Across Europe and the United States, capitalism ceased to appear among others and instead became the assumed destination. Center-left leaders such as Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, and Gerhard Schröder advanced a “Third Way” that promised to align markets with social justice. Globalization was framed as inevitable and largely benign. In Europe, this sense of stability was institutionalized through the expansion of the European Union and the introduction of the euro, making political and economic integration appear irreversible. Growth was expected. Technological progress, financial expansion and rising consumption. Environmental risk, inequality and geopolitical tension were acknowledged, but treated as manageable within an otherwise stable trajectory. Only later would the 2008 financial crisis expose how fragile that confidence had been.

How 1990s and early 2000s stability became the baseline for today’s political and cultural anxiety

The current political-cultural period is widely described as an era of populist mobilization and affective polarization, digitally mediated political communication and intensified culture-war conflicts amidst broader global democratic strains and structural change. Under conditions where new futures fail to take form, recombination becomes more reliable.

Cultural theorist Svetlana Boym distinguishes between restorative nostalgia, which attempts to rebuild a lost past, and reflective nostalgia, which lingers on loss. The contemporary return to the 1990s belongs to the latter. It does not aim to reconstruct the decade. It circles absence. The sense that institutions functioned and progress still carried weight. This became the baseline against which the present is measured.

Why nostalgia for the 1990s reflects a lost worldview of liberal optimism and imagined progress

The fixation on the mid-1990s and early 2000s persists because the period marks a collective threshold. It was the last moment when the future still appeared open and largely unthreatening. Last moment before 9/11, wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, 2008 financial crisis and the always-on brutality of social media.

Nostalgia attaches itself to this interval. What returns now is a worldview shaped by the end of the Cold War, faith in liberal democracy, and an economic imagination that assumed growth could continue indefinitely. The 1990s were confident. The early 2000s extended that confidence long enough for it to feel natural. The shocks that followed turned the period into a symbolic “before.”

How 1990s and early 2000s nostalgia reshapes fashion, identity, and visual culture today

Fashion provides a precise measurement of this shift. In the early 1990s, Grunge emerged as a tactile rejection of 1980s excess, favoring thrifted layers and a deliberate lack of polish. This aesthetic served as the visual foundation for a culture that prioritized raw authenticity over corporate presentation.

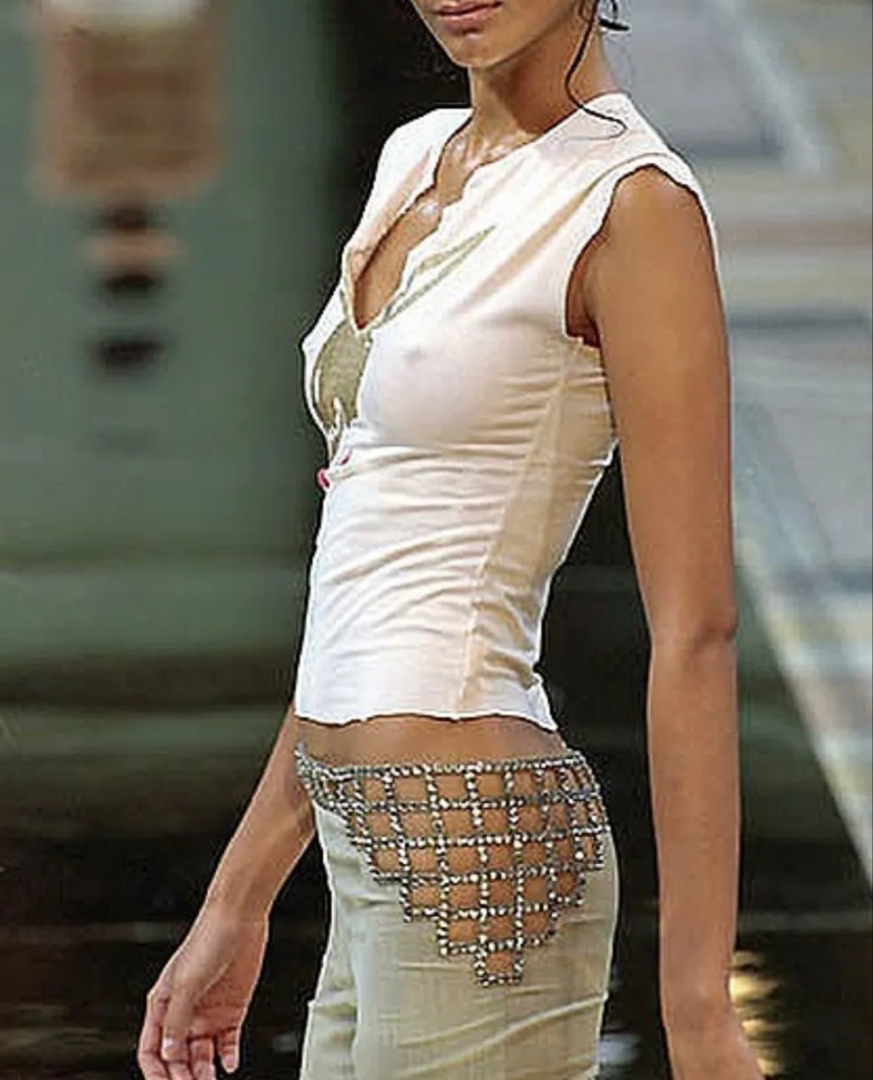

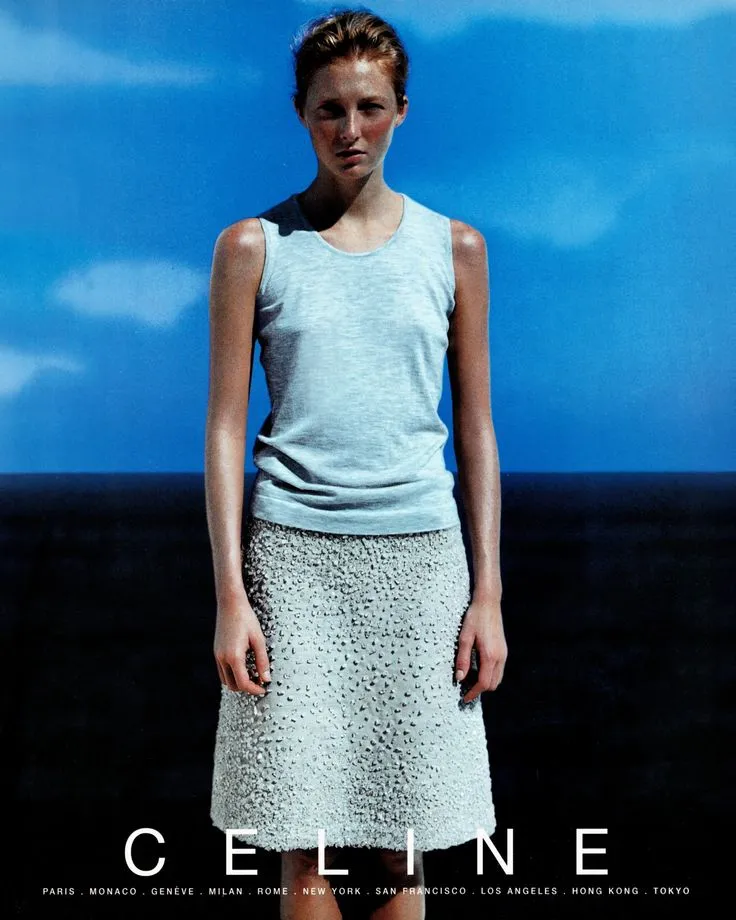

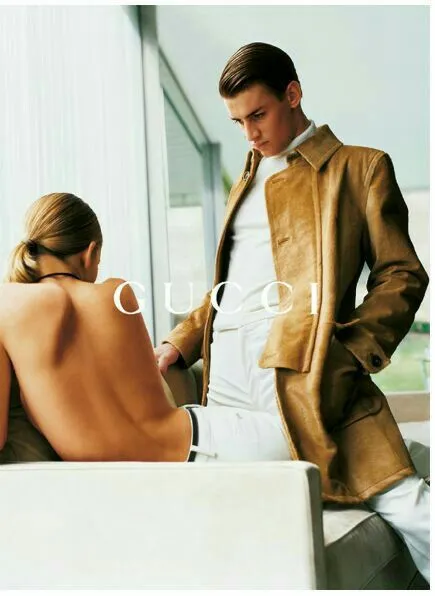

In the mid-1990s, clothing was minimal and calm, aligned with the order of the Third Way. Designers like Helmut Lang, Jil Sander, Calvin Klein, and Miuccia Prada built collections around clean lines, technical fabrics, and restrained palettes that reflected a broader confidence in social structure. The subsequent dot-com boom introduced mass access, digital media, and a new celebrity culture. The expansion of the consumer internet and global image circulation transformed the landscape. The Fendi Baguette, launched in 1997, became the first widely recognized It-bag within this emerging economy. It was small, logo-driven, and instantly legible, marking the transition from the realism of the early 90s to the collectible logic of Y2K.

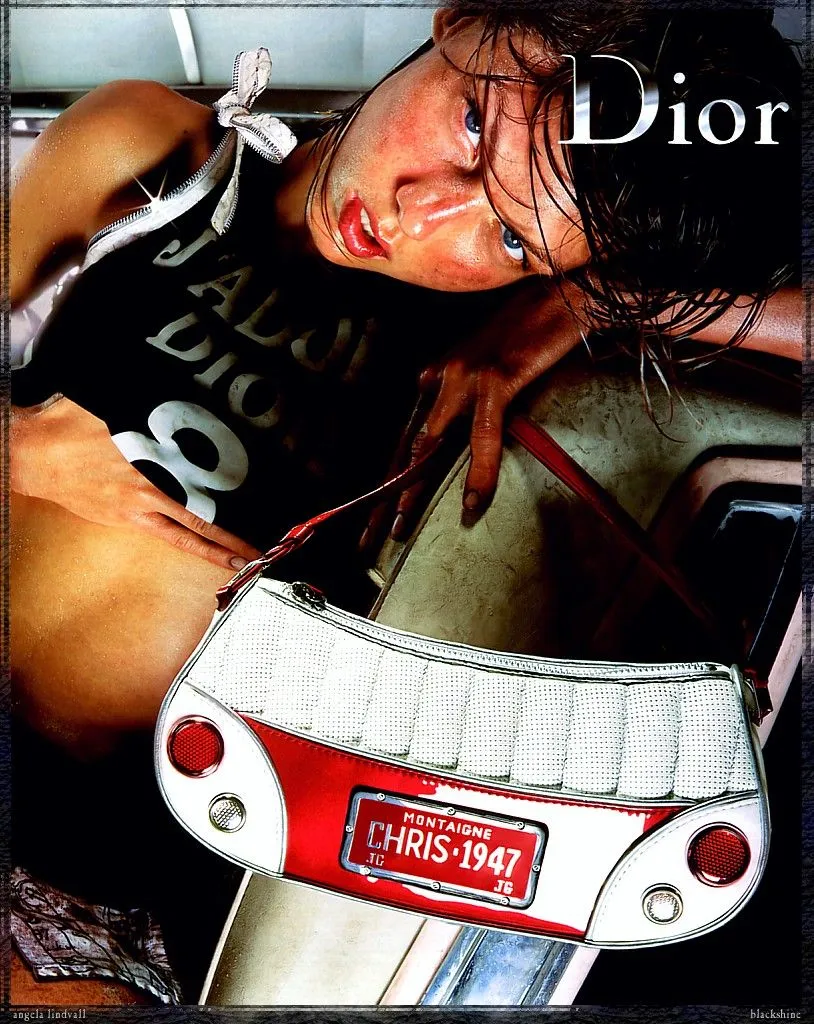

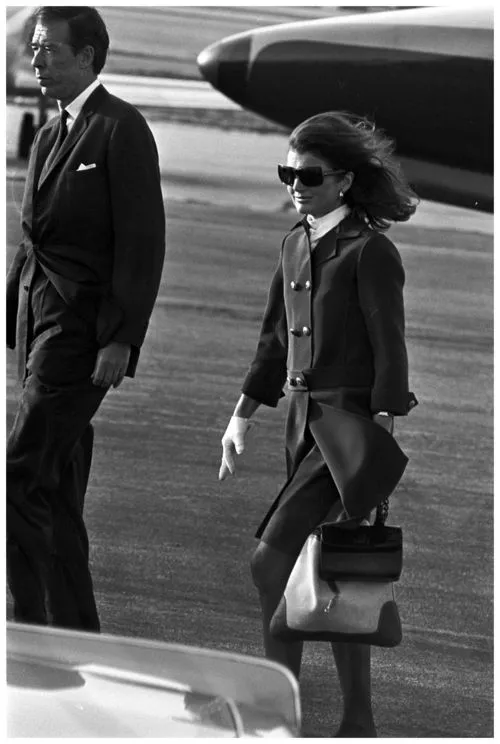

Following the events of 9/11, political trust and economic security declined. Public life became more stressful and vulnerable, and visibility ceased to feel neutral. Fashion mirrored this period through designs aimed at managing public perception. Tom Ford’s reimagining of the Gucci Jackie was directly inspired by Jacqueline Kennedy’s use of the original bag to shield herself from paparazzi. This transformed the accessory into a tool for controlled exposure, rooted in the legacy of a political figure who navigated intense media scrutiny. Simultaneously, the Dior Saddle employed a bold, architectural design to contour the body for photography, enhancing the prominence of the wearer while regulating how that prominence was consumed.

The return of Y2K silhouettes, including low-rise denim, jersey stretch fabrics, and tattoo prints, signifies a desire for an era when identity was expressed through bold visuals but had not yet become constantly monitored. The systematic re-editions of icons like the Fendi Baguette, Dior Saddle, and Gucci Jackie belong to the last phase of digital modernity before metrics and permanent self-display became infrastructural. By reviving these specific archived symbols, today’s culture attempts to reclaim a sense of digital privacy and aesthetic legibility. In a world of fleeting algorithmic micro-trends, these known silhouettes offer a stable identity. They provide a method to engage with the modern image economy without being entirely consumed by its relentless surveillance.

Skin realism, heroin chic, and the lost right to be un-optimized before digital beauty culture

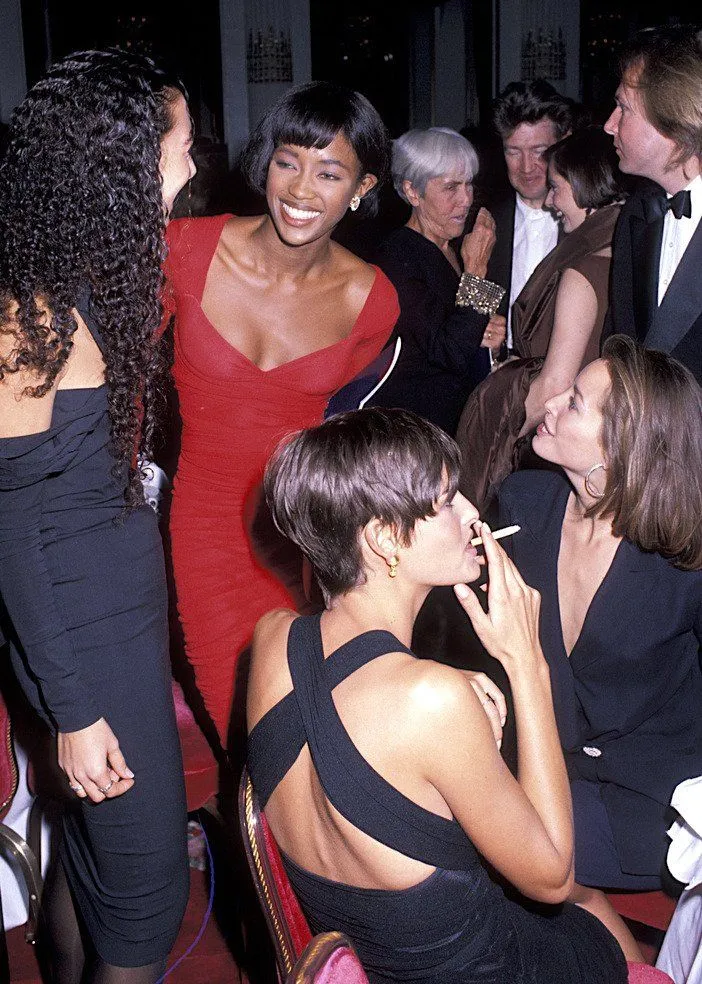

Beauty culture in the early 1990s remained anchored in physical reality. The supermodel era, defined by icons like Naomi Campbell and Christy Turlington, demanded extreme physical discipline, yet the industry still operated through analog film and physical runways. Faces were observed under pressure, but they were not yet technologically corrected in real time. This was an era of skin realism where irregularities and pores were requirements of the medium.

By the mid-1990s, a counter-reaction emerged. Heroin Chic, led by the early image of Kate Moss, shifted beauty toward a deliberate un-refinement. Dark eye circles and visible fragility became a visual protest against corporate polish. This was the beauty equivalent of Grunge. It favored the right to look un-optimized. The face remained biological, but it was now being used to signal alienation inside prosperity.

The transition into the early 2000s marked the collapse of skin realism. The rise of digital retouching and the professionalization of cosmetic injectables reorganized the face around maintenance. Beauty became a surface to be stabilized, designed to eliminate the glitch of aging. The face ceased to be an organ and became an interface.

The current obsession with uncorrected features reflects a strategic desire for the last moment when the face was a biological entity rather than a digital project. Today, a dual-layered return. First, a revival of mid-90s friction occurs through the sudden obsolescence of the filtered Instagram Face in favor of visible pores, hyperpigmentation, and the asymmetrical, thin brows of 1996. Second, we see a return to early 2000s glow, representing a rejection of matte perfection for the humid, high-shine textures of the Y2K pop era. By reclaiming these textures, the consumer asserts a right to exist without the constant, moralized pressure of algorithmic optimization.

Underarm hair, male body hair, and the politics of the un-managed surface

In the 1990s, underarm hair on women is not merely a “beauty” topic. It is a fault line where the image stops being fully sterilized. When hair appears, it rarely reads as glamour. It produces visual friction. It signals a body with biology that does not always collaborate with presentability. The 1999 Julia Roberts moment, later misread as an intentional statement, became a reference point precisely because it exposed how fragile the norm of the perfectly managed body still was.

Male codes swing differently. The 1990s still allow a rougher physicality: chests, body hair, sweat, a sense of desire routed through matter and exertion. By the early 2000s, grooming culture pushes toward a smoother surface. The face is cleaned up, the beard loses status, the body becomes more controlled and camera-ready under a vocabulary that would be labeled metrosexual. It tracks a broader shift: identity enters a maintenance regime. Fewer traces, more management.

A series like Queer as Folk sits exactly on that threshold—late 1990s into early 2000s—when desire is explicit but not yet fully captured by the infrastructure of digital surveillance. The show’s bodies remain legible as bodies, with the grammar of the club and attraction operating as a social space. Yet as the decade turns, a stricter, more screen-calibrated discipline creeps in. You rarely see unkempt beards in the Pittsburgh clubs. The look anticipates what comes next: visibility becoming obligation, and control becoming the condition of being seen.

How 1990s music created collective anonymity before the algorithmic attention economy

The renewed presence of 1990s and early-2000s music reflects structural conditions in which production developed before digital culture became standardized. In the early 1990s, music was the primary engine for Collective Anonymity. This was the era of the scene, involving physical spaces where individuals sought to lose themselves in the mass. Culture moved through broadcast radio and physical distribution rather than metrics, allowing sound to sustain duration rather than delivering an immediate payoff for an attention economy.

From grunge to trip-hop: sound, texture, and temporal density in 1990s culture

Chronologically, this shift began with the eruption of Grunge. In 1991, Nirvana articulated alienation inside the emotional polish of a culture that claimed everything was resolved. This sonic realism acted as the precursor to the minimalist fashion of the mid-90s. As the decade progressed, the Bristol scene, including Massive Attack and Portishead, translated post-industrial Europe into slow, urban sound. Like the restrained palettes and material clarity of Helmut Lang or Jil Sander, these genres refused excess for texture and presence over display.

In a landscape where a song must deliver a hook in the first five seconds to survive an algorithm, the 1990s represent a lost Temporal Density. This was the experience of a room hearing the same snare drum at the same millisecond without the mediation of a personal device.

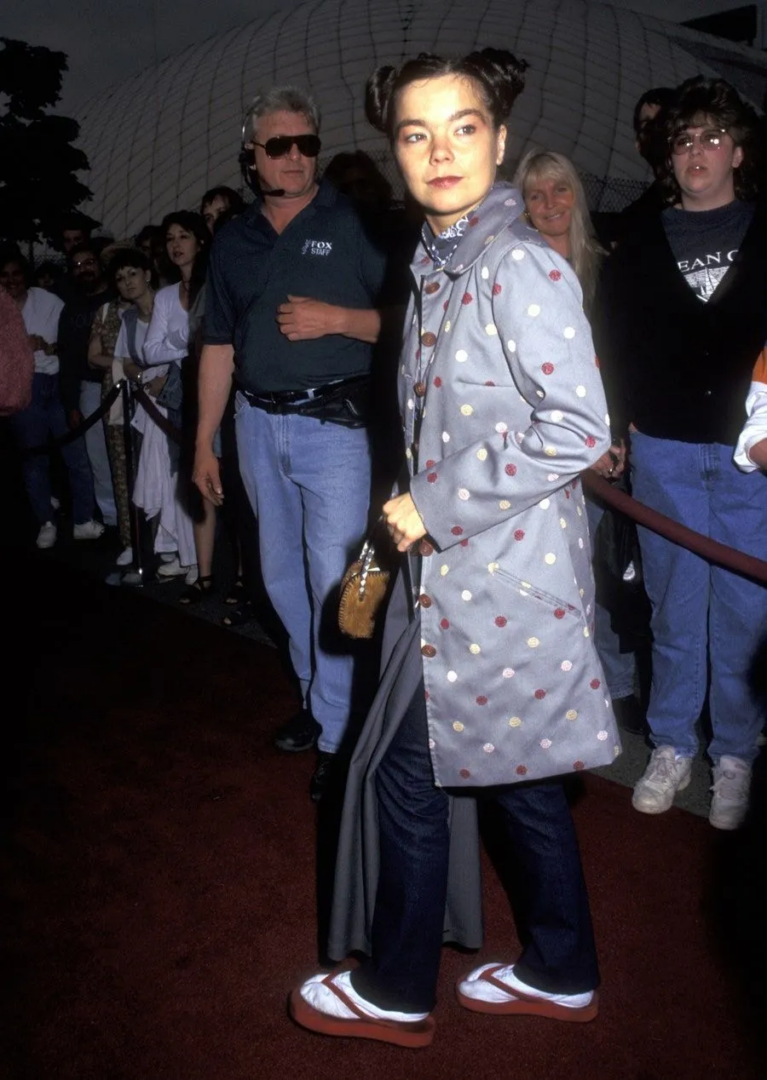

Why Björk, Rosalía, and Y2K club sounds return as resistance to frictionless digital music

This alignment began to break down in the late 1990s as music was reorganized around image. Björk’s Homogenic, released in 1997, marked this transition by keeping the interaction between voice and electronic production audible at the moment digital culture was becoming smooth and spectacular. Rosalía’s return to this lineage, specifically her 2025 single Berghain featuring Björk, reframes that late-1990s tension between body and technology. Where contemporary AI and high-end plugins make music perfectly frictionless, Berghain is a deliberate attempt to put the human back into the machine and show the seams again. These projects do not quote the 90s as nostalgia but as a method of restoring audible mediation in an age of algorithmic polish.

Cyber-pop, Eurodance, and the memory of an open internet before surveillance – and Charli XCX

This was the era of the glossy, loop-driven MTV soundscape that defined late-90s broadcast pop, where music increasingly functioned as a visual object designed for constant replay and recognition. That is why Eurodance, cyber-pop, Y2K club sounds, and Björk-style electronic intimacy now dominate fashion show soundtracks. These genres were built to survive cameras, loops, and visual circulation. They translate emotion into immediately legible atmospheres, making them ideal for a culture where music is consumed as much through screens and short-form clips as through sound

A similar logic shapes Charli XCX’s channeling of cyber-pop and Eurodance. These genres developed alongside the Open Web before surveillance and data extraction structured digital experience. In the early 2000s, the internet felt like a vast, lawless rave that was expansive and exploratory. Today, it feels enclosing and infrastructural. The current revival of these sounds references a moment when digital space was built for the collective. The sounds of the 1990s endure because they were born in the final window of friction, a time when technology was used to expand the limits of music rather than music being used to fill the limits of an algorithm.

How 1990s cinema trusted time, attention, and narrative drift

Just as design and sound developed in alignment with the Third Way political order, mid-1990s cinema functioned as the visual system of a world that believed in stability and structural continuity. Directors like Richard Linklater with Before Sunrise in 1995 and Wong Kar-wai with Chungking Express in 1994 operated on the assumption that time was an abundant resource. This was the cinematic equivalent of Material Realism. Where Jil Sander and Helmut Lang focused on the purity of wool and nylon, Linklater and Wong focused on the purity of the moment. These films trusted the viewer’s endurance because they existed in a confident media environment that had not yet been disrupted by the urgency of the digital.

This alignment began to break down in the late 1990s as the digital transition reorganized narrative around visibility. This shift mirrors the launch of the Fendi Baguette in 1997. Just as the Baguette transformed the bag into a communicative surface, early Sofia Coppola with The Virgin Suicides in 1999 transformed the film frame into the same logic. Meaning was no longer produced solely through the drift of character, but through atmosphere and recognition.

By the early 2000s, this image-led logic became dominant. Films like Lost in Translation in 2003 functioned similarly to the Dior Saddle from 1999. They were engineered for the paparazzi gaze of a new global audience. The narrative became a stage for aesthetics, where the look of isolation, captured in high saturation and high-definition digital palettes, displaced the grounded, naturalistic realism of the mid 90s. Time was no longer allowed to meander. It was now being formatted for availability, circulation, and the emerging speed of DVD and early internet culture.

Contemporary cinema returns to 1990s slowness to resist platform time

Today, cinema’s most compelling work — from Bi Gan’s surreal Resurrection at Cannes to Joachim Trier’s emotionally meditative Sentimental Value — resists the hook-every-five-minutes logic of the attention economy. These films privilege inhabiting time and unresolved narrative, recalling the slow-drift poetics of mid-90s directors. Even Richard Linklater’s self-reflexive Nouvelle Vague, which plays with cinema history itself, gestures toward a collective cinematic time that refuses instant payoff. Critics crowned both One Battle After Another and more introspective fare among 2025’s best, suggesting that audiences and critics alike are hungry for depth over immediacy

The persistence of these film grammars today reflects their position at a historical threshold. The return to the grainy textures of 1994 and the unresolved endings of 2003 is a diagnostic for present temporal exhaustion. Today, where platform time and retention metrics demand a hook every few seconds, contemporary cinema is attempting to reclaim the right to watch a story unfold without the constant pressure of a payoff. This represents a form of reflective nostalgia. Just as the Baguette and the Jackie function as tools for navigating the present, the resurgence of Lo-Fi Noir in 2025 serves as a tool for reclaiming collective time.

Ecological amnesia in the 1990s: when growth still felt compatible with sustainability

The most revealing dimension of this loop is ecological. During this period, economic growth, technological expansion, and rising consumption were widely understood as compatible with environmental protection. Climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource depletion were acknowledged, but they were framed as future risks. Environmental responsibility was discussed in terms of gradual reform, efficiency, and technological solutions. The underlying assumption was that progress could continue while environmental damage was managed over time.

This assumption no longer holds. In the years since, climate disruption, supply chain instability, and ecological limits have become directly visible within daily life. Sustainability now operates within a context of scarcity, regulation, and structural limits y.

The return of 1990s and early-2000s references reflects the memory of a period when environmental consequence had not yet entered everyday experience. That decade appears stable not because it was ecologically sustainable, but because its costs had not yet become unavoidable.

Today, this logic has reappeared in how sustainability is practiced. Environmental responsibility is again framed primarily through products, branding, and technological solutions rather than through structural limits on growth. Climate concern circulates widely as image and language, while production and consumption continue to expand. This reproduces the late-1990s condition, in which environmental damage was acknowledged but treated as something that could be managed without altering the underlying economic model.

Melis Özek