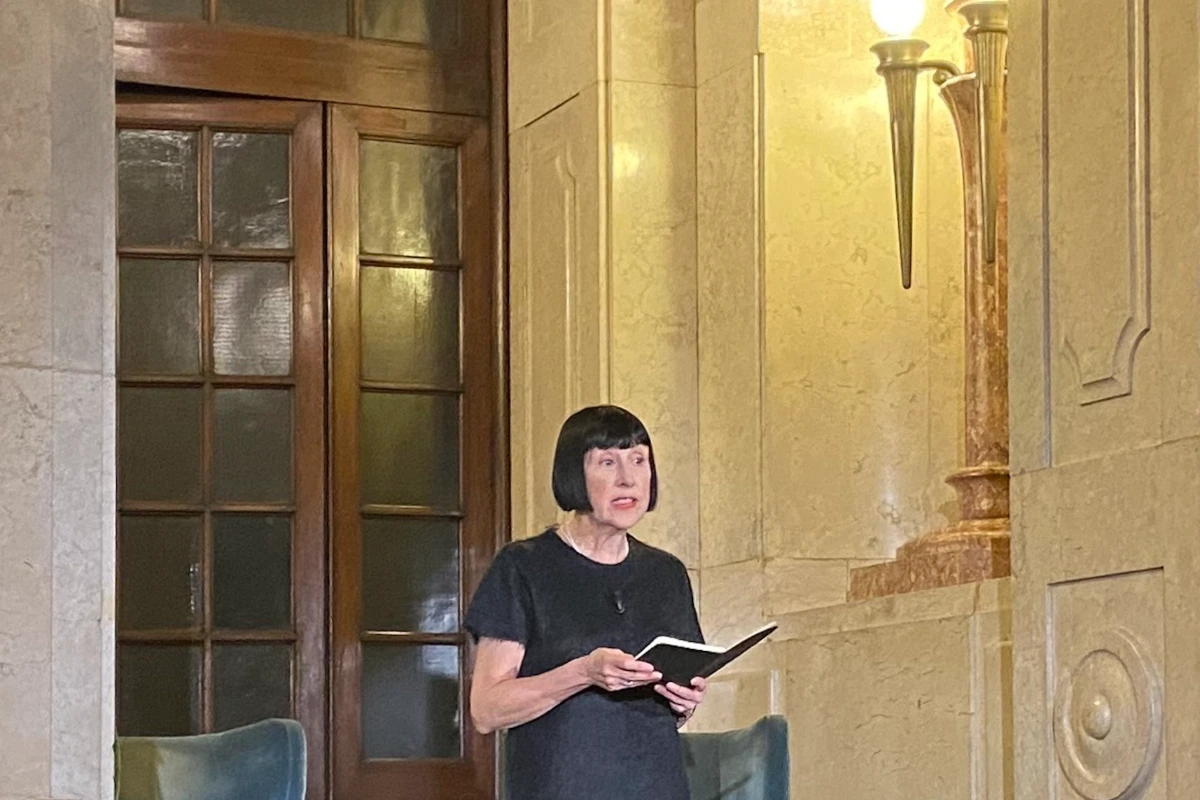

Alice Rawsthorn on design, critique, and global challenges at Prada Frames 2025

Inside Gio Ponti’s Arlecchino with design critic and former New York Times columnist, Alice Rawsthorn at Prada Frames 2025. “I felt design was misunderstood, marginalized, not taken seriously. There was a mission I could undertake”

Alice Rawsthorn in conversation with Lampoon

Alice Rawsthorn, one of the minds behind Design Emergency and a long-time design columnist for The New York Times, leads Lampoon up the steps and into Gio Ponti and Giulio Minoletti’s recently revived Arlecchino train—the locale for the 2025 edition of Prada Frames. The entrance gives way to a staircase so steep it delivers a bodily jolt, a sense that you’re stepping not just into a train, but into another era—one governed by different building codes than those that shaped the Trenitalia coaches lined up behind it at Milan’s Central Station.

Against the deep green of the Arlecchino, Rawsthorn’s pink satin heels, tipped with silver, catch the light. Of all the possible details to signal her presence—her voice, her intellect, her blunt bob—it’s the shoes that offer something tender. There’s a quiet confidence in that small design choice, as if to say: I’m here, I’m speaking, and yes—I’m wearing the pretty pink shoes. It adds to the aura of a woman so deeply embedded in the collective consciousness of the design world.

Her grasp of communication is pointed but never pretentious, sharp but never pop. Like the silver toe of her Prada pump, it leads the way—onto the train, into the dialogue, and through the world she helps us see more clearly.

Formafantasma, In Transit, and Prada Frames 2025

Annalise June Kamegawa: You’ve been part of Prada Frames since the inception of the program. How have you seen it evolve over each edition? Is there something within In Transit that has been accomplished for the first time?

Alice Rawsthorn: “The objective of Formafantasma (Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin) and Prada, who’ve collaborated since the start, was to add critical discourse to Milan Design Week. It was the biggest global design event of the year, but no one really talked seriously about design in a wider context.

They’ve continued to fulfill that original mission while always introducing new elements to it. They’ve identified really interesting general themes for the whole symposium and brought in speakers from all over the world.

Also, it’s been wonderful to discover beautiful historic buildings in Milan and amazing things like the Arlecchino train. In Transit, with its location, has taken Prada Frames to a different level in terms of the experience. With each edition, the event itself has grown with stature, not just within Milan Design Week, but also within the international design community.”

Working with Paola Antonelli on Design Emergency

AJK: Often in your work, you’ve cited Formafantasma as a case study in good design. In terms of your other collaborator on this event, Paola Antonelli: How did you first meet and how did you begin to work together?

AR: “Paola and I have been friends for years and years—so long I actually can’t remember when we first met. We obviously bonded over a mutual love of and obsession with design and we were lucky enough to be invited to many of the same international design events to speak. We would meet several times a year. Whenever I went to New York, we’d get together for lunch or dinner; ditto whenever Paola was in London and so our friendship really grew. We’d always contributed to one another’s projects and talked over ideas we had.

We’d always wanted to collaborate on a project that we developed together from scratch as friends. During COVID’s first lockdown, we were zooming, as you did with your friends during that period. I had started a series on my personal Instagram called Design in a Pandemic, which was obviously a response to COVID and the global design response to it. Paola was really interested in it and said, ‘why don’t we think of a way of developing the series?’

The idea came. I had been researching and identifying the global leaders participating in different aspects of the design response: designing public information campaigns, the spiky blob image that symbolized COVID as its official medical illustration, and so on. We decided to use Instagram Live as a platform to interview global leaders in the design response to Covid about their work. They were obviously all over the world and in very different circumstances. We focused on design for Covid for the first 10 weeks. We started in Spring 2020 and it was a big success—we had a fantastic response to it.

Our real goal has always been to raise public and political awareness of design’s role as a social, political, cultural, and ecological tool that can really help us to crack complex challenges. We felt that the amazing global design response to COVID would help that. It was really a great example of what design could do in this global calamity.

Then we focused on our endgame which was the elemental role of design as a tool of positive change. Now Design Emergency, much to our astonishment, is nearly five years old. We didn’t have any agenda or expectations for it. We certainly didn’t think whether it would still be going in five years time. It’s been great fun and we’ll carry on doing that. We’re happy to have it.”

Contextualizing and moderating for Prada Frames

AJK: Are you part of also the program curation for Prada Frames?

AR: “No, not at all. If Andrea, Simone, and their team ask me for my opinion or for specific suggestions, I’ll give it to them. But it’s curated by Formafantasma. They identify the theme, discuss that with the Prada team, and understand how it can be developed.

I’ve just been incredibly lucky that every year they’ve invited me to be part of it, which has been really fun.”

AJK: You’ve been a moderator for Prada Frames for many editions. Is moderating these live conversations something that came naturally to you as a writer? Or is this something that you had to adapt to?

AR: “For Prada Frames, I would describe myself as a moderator, but really what they ask me to do is to contextualize. But it would sound preposterous and pretentious to describe myself as a ‘contextualizer’ and I’m not even sure it’s a word. I give an introductory talk at the beginning of each session which puts the specific issues that are being addressed into a broader political, cultural, and ecological context.”

A journalist in many media

“Throughout my career as a journalist I was very lucky. I didn’t set out to do any of these things, but I would regularly be invited to be a talking head on TV programs. Then, with an experienced TV production team, I made small films for use on news and cultural programs or documentaries. I also gave lectures and talks appeared on the radio a lot—here, you are using your voice rather than words as a communication.

I always see myself as a writer. When people ask me what I do I say, ‘I write on design,’ but actually those other media of communication take up more of my time. I have no training in them, and I didn’t set out to pursue them, but they became really interesting additions to my broader work in design.

When I graduated from university I was a Times graduate trainee—I received a very nuts-and-bolts journalistic training. I also received brilliant training at The Financial Times from the discipline of working in such a rigorous platform. I apply those journalistic techniques, which initially were simply for publication in an old-fashioned printed newspaper, to all these different media and I really enjoy that. I don’t know whether I would still want to be a writer-type journalist if I had continued to practice the profession in the same way throughout my entire career.

I tend to approach design similarly to when I was a foreign correspondent. We had to cover all aspects of life in France—politics, economics, corporate affairs and so on—and I treat design as if it’s a country and I’m responsible for it as a foreign correspondent.”

Critique, admiration, and the pursuit of better design

AJK: Even as a critic, your writing is often marked by admiration for the people you write about. How did you come to that approach in critique?

AR: “I became a design critic having spent over 20 years as a general journalist. After being a foreign correspondent at The Financial Times, I wanted to focus on one subject I was really passionate about. I chose design. I discovered it by accident when I was a student reading the great Italian design journals of the late seventies and early eighties.

I felt it was misunderstood, unfairly marginalized, not taken seriously, and its power underestimated. There was a mission I could undertake to raise expectations of it so it would be used more widely to address complex issues: that had been my objective from the start when I was The New York Times design critic and then through my books and Design Emergency.

One thing I always did was also write about the negative side of design and what happens when it goes wrong. Whilst I have huge admiration for the often unfairly obscure design heroes and heroines of the past, I’ve also always focused on what went wrong. By being honest about that, it’s the only way people can actually take the subject seriously. Those failures are something that design culture, like every culture, has to own. When I did this, it was slightly unusual in design criticism, which had been much more celebratory.”

The degrees of success in humanitarian design

AJK: You often write about environmental and social justice in design, but no single product or system can serve every individual need. When designing, how do we decide when it’s better to hold back—and when it’s worth going forward? I suppose this is really a question about risk assessment and the cost of progress.

AR: “I think probably a designer, which obviously I’m not, could answer that more fully than I can. I think what we do have to do is celebrate the potential of design and help intelligent, responsible, sensitive, and aware designers to realize plausible, credible, and achievable plans whilst also raising the alarm about sloppy design practice.

If you look at humanitarian design in the late 20th and very early 21st century, there were a litany of ambitious, publicized, hyped projects that then failed dismally.

There were many other examples of ambitious failures like the PlayPump debacle. It was a US non-profit foundation with the idea of installing merry-go-rounds in parts of African countries with little or no access to clean water and embedding pumps within them so that children could play pushing the merry-go-round around and pump water up. Children can’t play 24 hours a day: they don’t want to. The pumps ended up being broken, abandoned, and again, there was no repair strategy.

High profile failures like that raised the alarm about design and sapped the confidence of politicians, NGOs, and philanthropic foundations. But in recent years, we’ve seen so much incredible work on an increasingly ambitious, strategic scale and I think that is why design is taken increasingly seriously by politicians and other power brokers. It also can generate the funding it needs, whether it’s from crowdfunding or big foundations.

All of that has been very encouraging, but design protagonists have to accept that, just as every intelligent and sensitively designed success is a step forward, every sloppily designed flop is several steps backwards. It affects, not just them, but the credibility of all designers.”

Covering the design response in Ukraine

AJK: In your introduction of Lorenzo Pezzani and Marta Foresti’s lecture at Prada Frames this morning, you mentioned how the motorway journey from Beijing to Tianjin left an impression on you. Design and journalism can take you to very interesting corners of the world. What is an unexpected place this career has brought you to?

AR: ““The most fascinating trip I’ve been on recently was to Kyiv. I had covered the Ukrainian design response to the war since the outset which has been fascinating, but also heartbreakingly sad. Ukraine has led the world with the network of underground hospitals and emergency medical clinics that they’ve designed and built close to opened by the frontline. It’s a subterranean network, obviously, so it can’t be detected by Russian bombs. There are also the trains they’ve repurposed as ambulance trains with operating theatres and intensive care units. The Ukrainian design response has been phenomenal.

Through the work I’d done on the design response to the war, I had made a lot of contacts in the country. Going there to meet people and learn their personal circumstances during the war was a different dimension.

Tech designers and a lot of the creative industries are exempted from conscription because they earn so much foreign currency for the economy. That is regarded as their most valuable contribution to the war effort and all of them accept that it’s their contribution. Though many of them spend their free time volunteering to help the military, by taking on administrative responsibility for particular groups, for example.

However optimistic and courageous all the people I met were, when you spoke to them, they have all lost someone they love. Among the many problems the country is going to have to deal with are the mass trauma of children and the huge number of amputees caused by drones. That visit to Ukraine was unexpected It’s something I wouldn’t have done had it not been for my work on the Ukrainian design response to the war.”

Responsibility in design and journalism

AJK: That’s the most beautiful part of this job—the exposure to human narratives.

AR: “It’s a privilege but the quid pro quo is you have to respond responsibly and be as accurate and sensitive as you possibly can be while identifying the issues, the causes, and the developments that are going to make people want to read.”

AJK: It’s very tricky to bring empathy to truth. I think it presents a constant tension.

AR: “But then I suppose that’s the only context it should be brought into.”

Alice Rawsthorn

Alice Rawsthorn is a design critic and author whose writing has appeared in publications such as The New York Times and the Financial Times. She co-hosts the podcast Design Emergencywith curator Paola Antonelli; the duo also co-authored a book of the same name. At the 2025 edition of Prada Frames—In Transit, held during Milan Design Week—Rawsthorn contextualizes the contributions of guest speakers exploring the impact of design. The symposium is curated by Formafantasma (Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin) in collaboration with Prada.