Amanda Wall turns to the bed—not for rest, but for resistance

In an era where everything digital dissolves into vapour, Amanda Wall insists on stains, scars, and brushstrokes that mark time and presence—We’re leaving the rug, this is our life

Amanda Wall paints a world on the brink—where daily life is lived between doomscrolls and dissociation

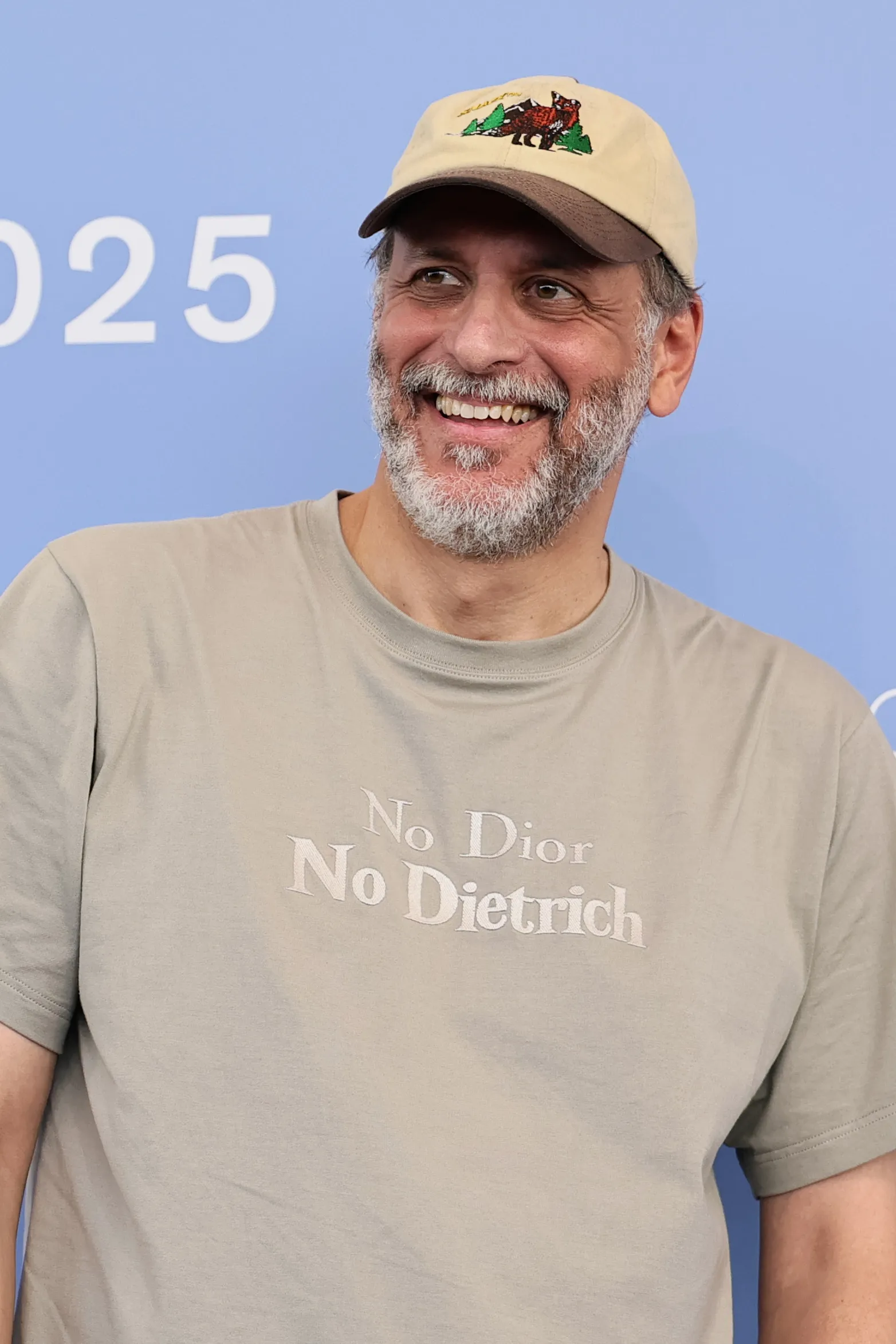

LA-based painter Amanda Wall arrived at her studio to a series of highly choreographed theatrics. Giant tanks rolled through the street, helicopters circled overhead, and 90 members of the armed national guard—some on horseback—descended upon an all but empty MacArthur Park. Born in Oregon, Wall moved to Los Angeles in 2011, drawn in by an ‘edge’ she once described as “apocalyptic”. Fourteen years later, that edge feels closer to collapse.

The past few months have seen the city’s once-exhilarating unpredictability descend into near dystopia—scarred by devastating wildfires, curfews resembling martial law, and a slew of militarized immigration raids, including one she witnessed firsthand.

The surrealist scroll and algorithmic anxiety behind Amanda Wall’s latest body of work

Blink and you might have missed it. The raid—an intimidation tactic with no known arrests—was over in minutes, and footage was quickly swallowed by the feed, overridden by anthropomorphised AI eggs, celebrity surgeries, and livestreamed genocide.

Such is the surrealist scroll we absorb and then forget—every image and atrocity flattened into sensory overload.

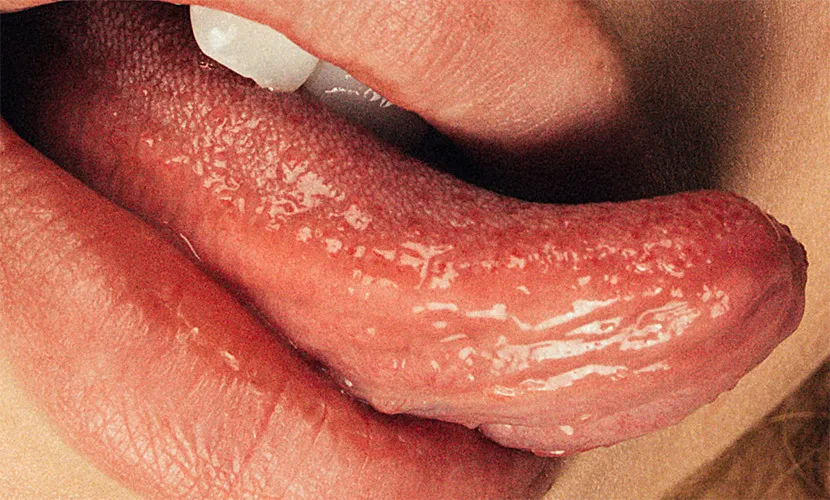

This dissonance—the simultaneity of horror, pleasure, mundanity, and responsibility—is what Wall’s latest work confronts. Her paintings occupy a psychic space of collapse and overflow, where we are unable to compartmentalise anything: joy, death, arousal, despair, the to-do list.

“It came from this idea of disassociating from the world via bed,” she explains. “Basically, our entire lives can be lived in bed now—our relationships, how we work, how we communicate.”

The bed as battleground: desire, disassociation, and digital decay in Beddy Byes

Her show at Almine Rech orbits around the bed—not just as a site of rest, but as a node of passive consumption, retreat, and refusal. The bed becomes a cocoon and a trap. A zone of intimacy and isolation. A portal and a prison. A place to rot, recharge, disassociate, desire, scroll.

Where Wall’s earlier work leaned into hyper-saturation, self-portraiture, and lush bodily excess, Beddy Byes marks a shift: the palette is more muted, the bodies more fragmented.

There’s a sense of dissociation specific to life under algorithmic siege—where the news hits from all angles and every app.

Its title, an affectionate childhood term for bedtime, feels deceptively innocent. Beneath it lies the real question: How do we remain present in a reality that feels increasingly unreal? How do we metabolize a world that invades even our most private spaces?

Wall doesn’t offer answers, only atmosphere—textures of affect, of living online and under threat, of scrolling and sinking deeper into the sheets. The body, like the mind, is suspended: fragmented, flickering, trying to make sense of the feed.

An interview with Amanda Wall on fractured realities, algorithmic vices, and the desire to disappear into bed

AW: The main idea for Beddy Byes was a kind of removal from the world, and this notion of a fragmented self and fractured reality. That’s what’s happening right now—individually and socially. It’s just how our lives are. Every image I look at on a screen, I’m like: “Is it real?”, “What does this mean?” I’m always questioning.

HS: What does your algorithm feed you?

AW: I’m an Instagram girl. It’s a whirlpool of meaningless slop, and I guess I’m still there for it. I’m happier if I’m away from my phone, but that’s partly because I’m constantly alone. There’s no accountability. It’s my dopamine. My phone, my vape… my vices of choice.

HS: At least AI has re-injected some kind of creativity into the content I’m seeing.

AW: It’s the only interesting thing that’s happening in culture. It will probably be the death of us—but there are worse ways to go, maybe? It’s a tool. You want a reference image with a specific lighting and angle, and you can instantly make it. It’s ridiculous to say you don’t use AI—unless you’re morally opposed to it, but if you’re not, it would be like not having a phone.

Painting as instinct and process: Amanda Wall on flailing technique and self-taught freedom

HS: Has the new subject matter changed your process?

AW: I’m still painting the same way—flailing. [laughs.] I’m self-taught. I always say I don’t know how to paint, but that’s a good thing. You’re more open to experimentation. Every painting is an experiment where I don’t know if it’s going to work at all.

There are different iterations of that through portraiture, body composition, and a few still lifes—variations of things I’ve touched on in the past.

You mimic things in the beginning because that’s how you learn. Even as a child, I painted Monet’s water lilies. I didn’t intend to be self-taught; I just started messing around. I had no intention of being in the art world. It was trial and error—buying terrible, cheap materials and amusing myself.

From voids to bed core: Amanda Wall redefines intimacy and interior space

HS: Is your work always figurative?

AW: I’m interested in the human experience, and in narrative—or non-narrative—around that. I’m not a landscape girl. I wish I could paint landscapes, but no. It doesn’t interest me.

HS: How do you decide where to situate a figure?

AW: My earlier work used vibrant colours, bold voids, isolated figures. Now the palette is muted. For this show, I’ve moved into interior-esque spaces—more information, more texture.

They’re specifically “bed core”: sheets and blankets becoming environment and architecture. There’s no real room or depth—anything beyond the blanket slips into a black void, a nowhere space.

HS: In one painting, six cherries seep into the bedsheets—stains running everywhere.

AW: A stain is like a scar. Permanent. You can’t get rid of it. It’s evidence that something really happened.

When I first started painting, I worked in a shitty apartment corner. The rug was always stained—wine, paint. I’d try to clean it and my boyfriend would say, “No, leave it. This is our life.”

I’m a little OCD—I don’t like mess or disorder. Accepting a stain felt like accepting freedom.

Painting against control: intuition, waiting, and the refusal to explain meaning

HS: Do you need structure in order to work?

AW: I’m not clean OCD—I’m order OCD. Things must be in their places. I need visual calm. I can stay in the studio all day and not know if anything will happen.

Painting is mostly sitting, looking, waiting for the moment when something solves itself.

My work is intuitive. If it becomes too planned, it becomes illustrative in a way I dislike. The narrative around my work has been “she’s painting herself.” I’m bored of that. I never meant to make self-portraits—I was just there.

This show is different. It’s the first time there are boys. No individual figures—just groups, fragments of groups. A fragmented self. Viewers can interpret freely.

HS: Do people misunderstand you?

AW: Always. But you surrender. The work isn’t yours after it leaves the studio. People ask, “Is this about this?” and I say: “No, but I’m glad it’s yours now.”

From digital vapour to physical mark-making: Amanda Wall on the need for tangibility

HS: Your background is in fashion and architecture. How did you end up painting?

AW: I loved painting in school, but couldn’t afford to do it recreationally. Painting is a privilege—it’s expensive. I’ve always been obsessed with images, but painting gave me something physical—something that can’t be deleted or dissolved into digital vapour.

At the peak of social media, I realised I was always on my phone. I needed to escape—or create another kind of space.

Artists say, “I wasn’t really there when I made that.” It’s not quite out-of-body, but you are in a zone, almost gone.

HS: A paradox—physically present but disembodied.

AW: The best paintings I make, I look at them and think: “How did I make that?”

Harriet Shepherd

All paintings from Beddy Bye exhibition @Almine Rech Paris, Matignon, photography Dana Boulos