Andrei Ujică: An Aesthetic Eye on Revolutions

From the fall of the Soviet Union to the arrival of the Beatles, the Romanian master filmmaker Andrei Ujică’s work draws on archival footage to depict the upheavals of the Twentieth century

Interview with Andrei Ujică – Discovering the Beatles in Soviet Romania

CB: Andrei Ujică is a Beatles fan. Born in 1951, he was a teenager when the British Invasion swept the world, and he couldn’t help but be carried away by the beat phenomenon. There’s a difference between being a teenager in a Western country and being one in Soviet Romania. The first question is how the Fab Four’s music so quickly crossed the Iron Curtain between the West and the Red East. He is chain-smoking Tuscan cigars and sipping a double espresso in a café in central Milan. A few hours later, he would be giving a talk at the Triennale for the Fondation Cartier.

AU: I’m from Timișoara, one of the westernmost cities in Romania. My mother was an agronomic engineer, and around 1962, when I was ten or eleven, she was reassigned to production as Stalinist collectivization was winding down. So they moved us even further west, to a little village eighty kilometers from Timișoara.

CB: Already near the West, Andrei now found himself living less than two kilometers from the Yugoslav border, in a village whose population was overwhelmingly German.

AU: My mother was half Austrian – she could speak German to the villagers who worked on the farms and in the factories. Every summer, all those who had emigrated to West Germany after the war would come back on vacation to visit their relatives. Many of them had children my age or in their teens, and they brought all their latest records. Where I lived, the pop culture revolution reached us at the same time as the rest of the West. In ‘mainland’ Romania, in Bucharest, to cover those six hundred kilometers, Beatlemania took at least two more years.

Radio Luxembourg and the Beatles Cover of Chuck Berry’s “Rock ’n’ Roll Music”

CB: From this privileged geographic corner of the Soviet bloc, Ujică and his friends managed to pick up the medium-wave signals of the crucial radio stations that disseminated pop culture, especially Radio Luxembourg. In 1964, somebody played the Beatles’ version of Chuck Berry’s Rock ’n’ Roll Music, featured on the band’s fourth album, Beatles for Sale.

AU: From that day on, we threw parties every night with that song on repeat. It was the only Beatles track we had. We’d listen to it all night, until six in the morning, just dancing. One morning I was on my way home – it was broad daylight. I drew the blinds and went to bed, but I couldn’t sleep. I realized that night we had truly dived headfirst into our generation’s sea.

In TWST / Things We Said Today, Andrei Ujică Freezes a Weekend in 1965 America: A Film About Two Parallel Revolutions

CB: In his latest work, TWST / Things We Said Today, Ujică uses the Beatles as an entry point to freeze a snapshot of a 1965 weekend in America – a few days packed with events that almost manage to explain the chaotic turbulence of the Sixties.

AU: I didn’t want to make yet another film about the Beatles. There’s an endless filmography about them already. I wanted to make a film about what the American critic J. Hoberman defined as the ‘Beatles effect’ – how the Beatles shaped our pop generation and the ones that followed.

CB: Having identified the moment of peak Beatlemania, Ujică also zeroed in on the place: Shea Stadium in Queens, New York, where on August 15, 1965, the Four from Liverpool played for the largest concert audience to date – 55,000 people.

AU: At the same time in Los Angeles, Black neighborhoods were rebelling against systemic injustices – during the Watts riots – and that New York was hosting a World’s Fair, I realized there was a convergence going on. Reconstructing that weekend through archival material would give a view of the entire decade. American society changed in those few days: the revolution of Black Americans for a dignified life; a cultural revolution among white youth that shook off old prejudices.

CB: Though the Beatles radiated inclusivity, championing Black Americans’ fight for rights, they arrived like a bolt from the blue, driven mostly by aesthetics – and only later by politics.

AU: Their political engagement wouldn’t surface until about three years later, with the 1968 Summer of Love. I wanted that to be clear: their revolution started with aesthetics – from the mop-top haircuts to the suits and ties and later the colorful, eccentric outfits. Perhaps that’s why it was so seductive and successful. Political revolutions don’t explode that quickly.

Making a Film with Archival Material: Andrei Ujică as Half Historian, Half Novelist

CB: Anyone who, like Andrei Ujică, works almost exclusively with archival footage has a responsibility. On one hand, there are hundreds of thousands of hours of forgotten video and audio gathering dust on dark shelves; on the other, the historical burden of selecting, refining, and delivering possibly the only version the wider public will ever see about a given event.

AU: The first film I made, Videograms of a Revolution, overlaps with the gradual downfall of the regime in Romania but also with the rise of the amateur video camera market.

CB: You can see the excitement and panic on the faces of those revolutionaries who seized control of Romanian national television, sweaty-palmed and dry-mouthed, as they proclaimed the end of Ceaușescu’s regime to millions of viewers.

AU: I can’t imagine making a historical film on a contemporary event without using original footage. I want to document reality, then interpret it, just as historians have always done. As for my responsibility, it’s no different from that of a historian working on past writings.

“All True Historians Were Writers Tackling Historical Themes”

CB: A historian inserts their own personal viewpoint. He tries to be as objective by filtering sources on a single event, when sources agree on. Even Tacitus imparted his own slant in his Annals.

AU: The truly great historians – aside from some exceptions – were all writers who tackled historical themes. From Shakespeare to Tolstoy, nobody surpasses the historical accuracy these figures achieved in their works.

2 Pasolini (2000), with Support from the Fondation Cartier – A Short Film Inspired by Pasolini’s Sopralluoghi in Palestina

CB: In 2 Pasolini, a short film produced in 2000 by the Fondation Cartier, the director starts from Pier Paolo Pasolini’s documentary Sopraluoghi in Palestina, created as research for The Gospel According to Matthew. One wonders why, in 2021, Ujică decided to revisit his work and re-edit it.

AU: At the time, they asked me not to include subtitles. So you had Pasolini speaking Italian and Jesus speaking French. I wanted Jesus to speak the language Pasolini had chosen – Italian. While I was at it, I changed a few cuts, but not much.

The funny thing is that in the documentary, Pasolini says he was disappointed by how modern the biblical landscape looked. The truth is he actually filmed many of the Holy Land scenes in Sicily, because he already knew Palestine no longer resembled what it was two thousand years ago. Let’s say his trip to Jerusalem was more a promotional expedition.

CB: Ujică draws a parallel between Tupac Shakur, the rap legend murdered in 1996, and Pasolini. The short ends with a remix titled 2 Pac 2 Pasolini, juxtaposing two prophetic figures who both met tragic ends yet remain revered for their art.

AU: That was a connection I wanted to underscore. Tupac was a rebel for his generation, much like Pasolini was a messiah of his art. In The Gospel According to Matthew, Pasolini laid revolutionary Russian songs over scenes of Jesus walking through Galilee. So I thought, ‘If he did that, then I’ll end my film with Tupac.’ I like his music; I discovered it because my son listened to him.

Transnational Cultural Shifts Triggered by Iconic Music Events

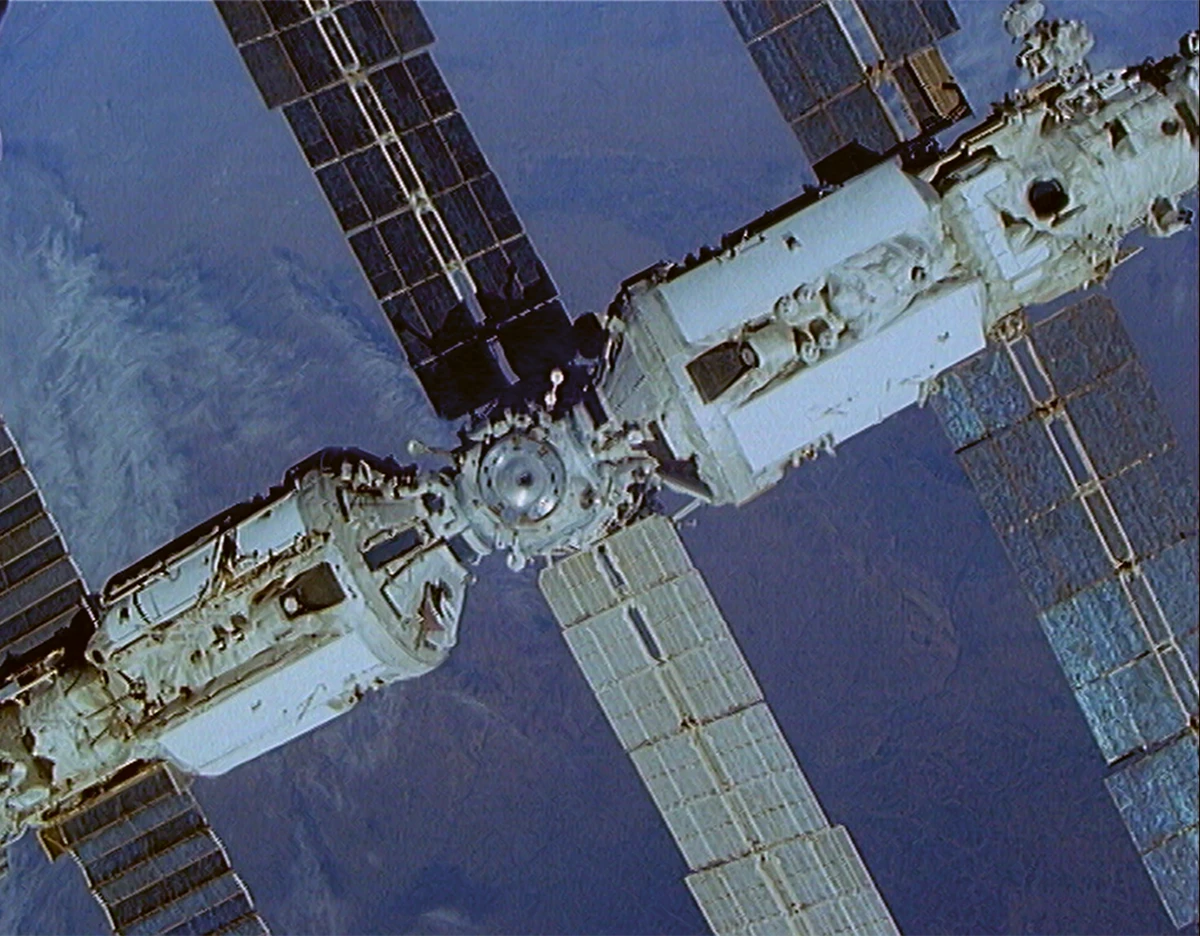

CB: Eurodance, techno, and trance underscore the images, serving as a kind of glue linking that present moment – the early Nineties – to the cosmonaut’s orbital isolation.

AU: On New Year’s Eve in 1991 – the first after the fall of the Soviet Union – there was a rave at the Cosmology Pavilion of the Moscow fair. I only arrived in Moscow two years later to make the film, but people at the government energy company told me about that rave. It marked the start of a new era for Moscow and Russia – nobody had ever heard German techno there before.

CB: One of the main reasons Ujică prefers archival material is one I suspected and that he confirms: there’s no need to ask producers for anything. There’s no epic hunt for the vast sums required to bring an idea to the screen.

Long-Form Documentary Funding Models and Budget Optimization

AU: Remember that in the Nineties, a film that wasn’t fiction was considered marginal niche. Today it’s a little better. Back then, finding genuine financial backing that understood your project was nearly impossible. Even my latest film on the Beatles cost about two million dollars. The network footage we had to buy – ABC, NBC, CBS – ran as high as 17,000 dollars per minute. I ended up with about fifty minutes of black-and-white material in the film.

CB: First the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, then the attack on a U.S. healthcare insurance CEO, then an attempted coup in South Korea, and finally the liberation of Syria from Assad’s regime. Someone like Ujică, who has witnessed and documented plenty of revolutions, should know one when he sees it.

AU: The West is crumbling. We’re witnessing a grassroots revolution from the most downtrodden elements of the capitalist system. Over the past few decades, there’s been a gradual, inexorable, and now total split between academia, the arts, and people’s everyday needs. The elites haven’t grasped or accepted that break. The handful of media outlets they control also fail to see the huge crowds who’ve turned their backs on them. The intelligentsia’s mistake, born of comfort, is the same as it was in the 20th century: not recognizing that socialism is an intellectual movement, while fascism responds from the gut to popular discontent. The same dynamic is at work today: it’s a grassroots sentiment demanding the privileges of the ruling class, which is by now completely alienated.

How Long Does It Take to Produce a Film Using Archival Material? – Andrei Ujică

CB: Andrei Ujică’s creative process for each film takes around five years. Between his The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceaușescu and the newly released TWST / Things We Said Today, 14 years have passed – quite a gap for the director.

AU: From the initial idea to developing the structure, then to researching and obtaining funding, it all takes time. Just reviewing archival material alone can take three years, plus a year for editing and another for post-production. In general, that’s five years.

This project was delayed by several misfortunes in the last strange decade. One was a family tragedy that brought the project to a halt for two years. Around 2015, I had rights issues with the Beatles’ Apple Records, so I changed the script – but that proved an artistic blessing. It made me realize that I could expand the film to the historical context of the ‘Beatles effect’ without getting hung up on the band’s story. Then came two more years of pandemic. So, in the end, we did spend five years on it – spread over three times that period.

Claudio Biazzetti