At the Biennale, it’s all sweat: a trillion trees—nothing else will save us

Introduction to Carlo Ratti’s Architecture Biennale: the lone subject is sustainability—a “mind-boggling” number of trees, humanity on its knees, sweat, heat, and a bacterial population boom

Heat and sweat in the Arsenale’s first hall: Carlo Ratti’s Biennale, Terms and Conditions

Carlo Ratti opens the Architecture Biennale catalogue with a blunt reminder: architecture has always answered a hostile climate. In 2024 the planet burned. Global averages pushed past the 1.5 °C ceiling set by the Paris Agreement; Los Angeles burned, Valencia flooded, Sicily withered. Cutting carbon alone is no longer enough. The Biennale’s prologue is a rallying cry—per aspera ad astra, through difficulty to the stars, and back again to Earth.

The first room of the Arsenale is a steamy wake‑up call: pools of water crank up the humidity, the temperature mimics a midsummer city on the plains, and suspended outdoor A/C units—the same plastic‑boxed grids that scar so many facades—hum overhead. The hall’s title, Terms and Conditions, demands that visitors acknowledge the fine print of collective discomfort: thermal stress, sacrifice zones, dependency. Before moving on, we must agree to the rules of survival.

The one and only topic: global overheating—heat, sweat, sustainability

“Sustainability” has been said so often it feels worn‑out, even irritating—yet there is nothing more cool, creative, or new outside its scope. We have to keep repeating the word until it becomes as taken for granted as the air we breathe; nothing should pass muster unless sustainability is baked into its foundation.

Our future against heat—our sweat and hard work: planting trees

As Lampoon has long argued—and as climate scientist Hans Joachim Schellnhuber documents even better—trees are among the few realistic survival strategies. Roughly one billion hectares of degraded land could host trees, but Schellnhuber calculates we would need five hundred billion to one trillion of them. It’s daunting, but not impossible. And planting isn’t enough; felled or dead trees release their stored carbon, so every sector—from construction to textiles, plastics, energy—must learn to use biomaterials. Alongside timber, hemp is often the most versatile.

Defining “sufficiency”: regenerate before you build—over‑population

“Sufficiency” traces back to the Greek sōphrosýnē and Latin sobrietas. Yamina Saheb’s Sufficiency First calls for repurposing idle structures before erecting new ones—and if something new goes up, the old must be demolished, recycled, and responsibly disposed of. France has a law for this; Italy does not. Abandoned industrial shells dot the countryside while brand‑new logistics and data hubs rise on greenfield sites. Production facilities should flank highways—and their backers should be obliged to clear disused buildings in rural areas, giving farmland back to communities.

Europe holds only a sliver of the world’s land and population, yet it once colonized most of the planet. Now it must be the engine of global experimentation—civic innovation, collective avant‑garde, a modern‑day Renaissance.

Giorgos Kallis vs. Thomas Robert Malthus: is urgency or idleness the wellspring of creativity?

Heat, sweat, over‑population. When humanity outruns its food supply, necessity is said to spark invention. Might over‑population actually drive progress? Ecological economist Giorgos Kallis contends that lazy leisure mothers imagination; the 18th‑century cleric‑demographer Malthus retorts that urgency, need, and daily want generate enterprise. Charity, for him, should elevate and foster self‑reliance, not lock people into dependence—“stern kindness,” he would write today.

Planet Earth: in a century we’ll top ten billion

The exhibition’s wood panels will be shredded and reborn as new boards, mounts, whatever comes next. Construction techniques, on‑site renewables, carbon‑sequestering natural materials, advanced cooling and heating, depaving, a plastic phase‑out—all are on display.

Yet sheer numbers loom. Scientists foresee a sharp population drop within the next hundred years. We are heading toward demographic decline—but what happens to the economy, which for centuries has thrived on growth? Will disease, disaster, and cataclysm be nature’s counter to over‑population, or will a gentler genetic shift—say toward greater human homosexuality—prove a blessing in disguise?

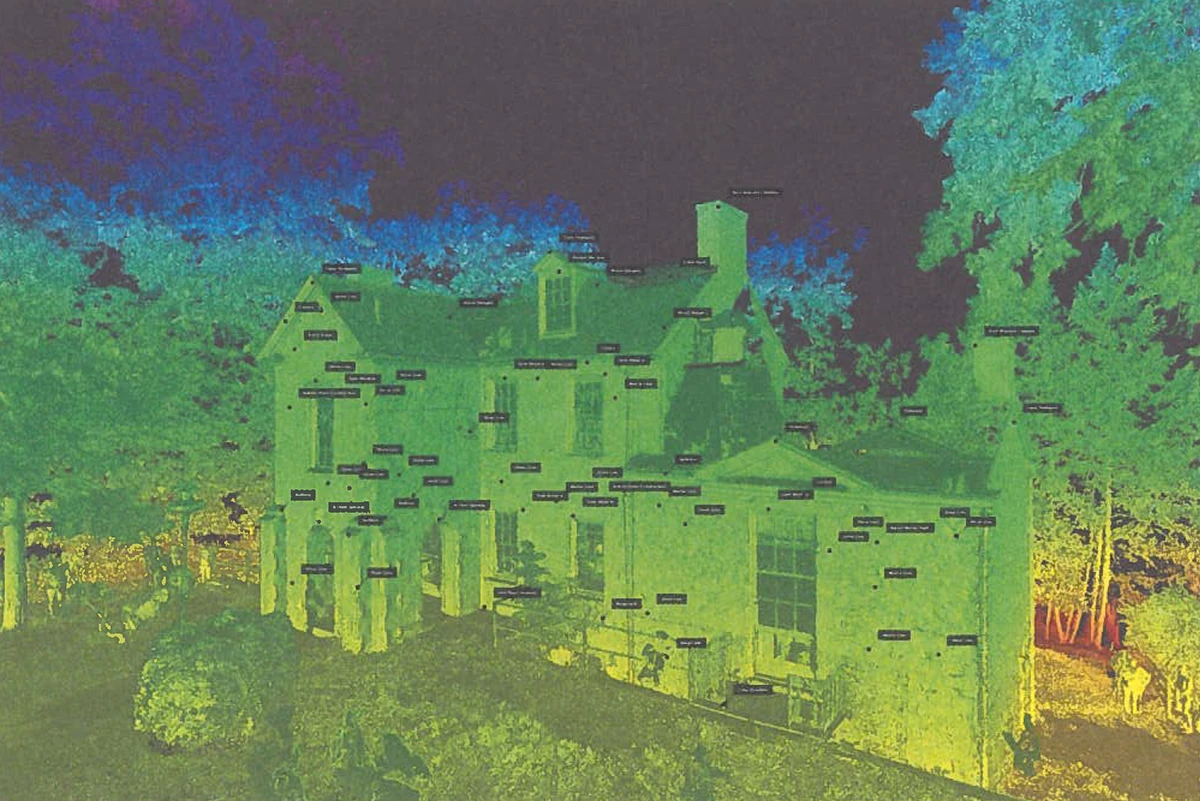

Beyond Terms and Conditions: The Other Side of the Hill

Past the first hall stands a brick wall by Cimento titled The Other Side of the Hill, a collaboration among Beatriz Colomina, Roberto Kolter, Patricia Urquiola, Geoffrey West, and Mark Wigley. The wall’s hyperbolic profile tracks population growth to ten billion; beyond that crest, a descent begins. What lies over the summit? Must decline look catastrophic, or can microbes—our heat‑ and sweat‑loving kin—teach us how to live with natural‑matter bricks before infecting us?

Carlo Mazzoni

Notes

Venice Biennale 2025: Rolex, official partner—architecture can speak of nothing else but sustainability

Rolex is not only the official timekeeper of sport, especially tennis; it has become a cultural brand, achieving an affective resonance other labels covet but rarely match. Far from diluting its aspirational gravitas, this emotional seeding amplifies it. Put simply, Rolex feels at once like a friend and a mentor.

Venice Biennale—Architecture 2025: technical note

Neither catalogue texts nor wall captions delve into the technical guts of the exhibited projects. The priority seems to be emotion, fascination, spectacle—whereas an Architecture Biennale ought to explain with precision and economy. Along the route the writing lapses into repetition, trading scholarly rigor for mass appeal. Over‑wrought rhetoric and buzz‑word loops distract more than they inform.