To Love Milan, We Still Need Armani

We need to insist on what Milan looks like. The city’s palette is gray, never flat, altered by rain. Armani, today under the direction of Leo Dell’Orco, remains the clearest expression of the Milanese logic

Armani: seriousness, irony, the body

We say Armani as shorthand, yet the first collection still carries his name: Giorgio. That distinction matters. Mr. Armani used to in total charge—design, image, every decision-making. Even without personal proximity, one understood this immediately. Giorgio Armani projected authority. He was deliberate, uncompromising, exacting. He took himself seriously. Irony belonged elsewhere, outside the work. That separation gave weight to everything he did. Respect followed naturally, and with it, today, we feel a bit of nostalgia.

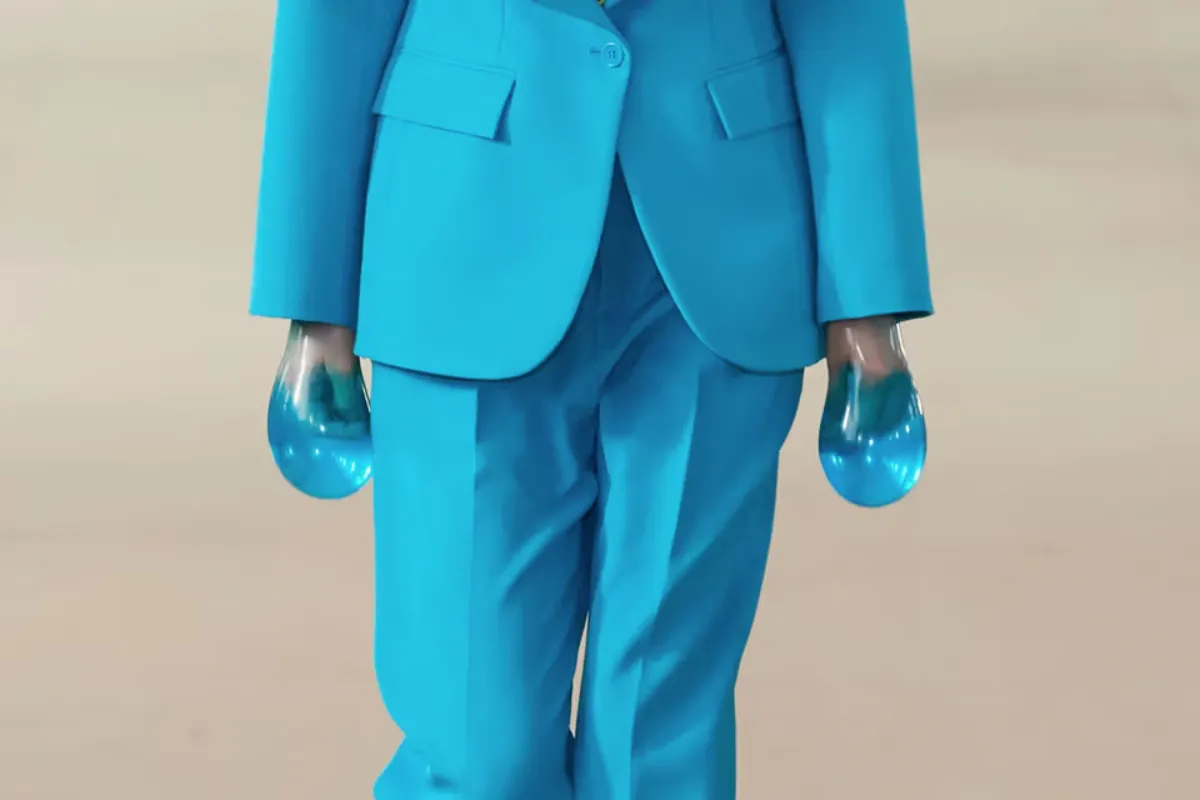

The point is not to erase that nostalgia, but to convert it. The clothes do the work. Trousers fall softly, engineered rather than relaxed. A belt loop becomes a technical detail, not a decoration. The casting search for sensuality. The male bodies recall Bruce Weber’s photography—classical, sculptural, closer to Michelangelo than to contemporary androgyny. There are not fragile silhouettes. There is no strategic ambiguity. The sexual appeal is frontal. Flesh is present. Muscles press against silk. The erotic charge is neither ironic nor diluted.

This choice runs against the current logic of the fashion system, which tends to standardize bodies into a neutral, flexible type. Armani resists that flattening. Under Leo Dell’Orco, the insistence on a virile, sexual masculinity is explicit. It is not nostalgic; it is operational. Even when it’s a revising process of the archive.

Armani menswear continues to define what fashion does for a guy. Sex sells. Armani sells. More precisely, sincerity sells. Sensuality here is not a concept; it is a fact. The eroticism of these clothes—variable, tactile, exposed—cuts through nostalgia and replaces it with desire. A desire for beauty, for proximity, for contact. Faced with this, much of contemporary conceptual menswear recedes. The intellectual posture gives way to something more direct, bodily, and deliberate.

Giorgio Armani, male beauty, the bourgeois city

Giorgio Armani was, quite simply, a very handsome man. Recently, his image returned to the collective imagination: sharp features, precise lines, as if drawn with ink and softened with watercolor. That image still projects forward. For Armani, male beauty is not incidental; it is structural. Physical attraction is not decoration but a driver of meaning. It may well remain the key to the brand’s future. Leo Dell’Orco himself began as a model. The continuity is not accidental.

Milan likes to describe itself as a bourgeois city. The term is used without discomfiture. Discipline and desire coexist easily here. If the body attracts, if the bed is wanted, that only reinforces the point. Armani makes this coexistence legible.

Milan is a city raised on manners rather than ceremony. Children were corrected quietly. If you misbehaved at the table, you ate in the kitchen. Conversation mattered. Posture mattered. Elbows in. Voice measured. Courtesy was practical, not ornamental. These children grew up playing tennis, studying Latin, learning how to occupy space without excess.

Milanese apartments reflect this ethic. Dining room and kitchen connected by a hidden tiny corridor. An antechamber mediating public and private. These were not expressions of hierarchy, but of efficiency. Formality, in Milan, has always been stripped of reverence. Formality belongs to Rome, with its exhausted aristocracy and its attachment to ritual. Milan prefers function. Politeness accelerates exchange. Encounters are efficient. Even etiquette as a word feels out of place.

What remains is a dry irony, a certain roughness in the smile, the severe eyebrow of an elderly woman—or of a master tailor. This is the cultural ground Armani emerges from. Milan, seen this way, is unmistakably erotic.

Via Borgonuovo: domestic scale

Via Borgonuovo 21. Below street level, a theater space few knew existed. Upstairs, the early salons. Stairs leading to a first-floor lunch: rice, risotti, involtini. Milanese food, without commentary. Windows opening onto an internal garden: lawn, magnolias, camellias, jasmine. A winter veranda for plants. Few works on the walls, except at the entrance: Andy Warhol’s portrait of Armani.

The layout is precise. An atrium. The main salon. A study to the left. It is the Milanese home at its most legible: urban, contained, intentional. This domestic scale explains more about Armani as a brand, than any branding exercise. If Milan is a city of people who act—who say “we’ll handle it”—then Armani is its most coherent interpreter.

Work comes first. Rhetoric is unnecessary. Impatience is allowed when things are poorly done. Conversations are brief unless they matter. Time is not wasted. Clothes must sit correctly on the shoulders, allow movement at the thigh. Comfort is not indulgence; it is a requirement. Feeling good in a suit is part of functioning properly. Physical training, like work, is a matter of discipline.

The runway: shifting surfaces

The fabrics clarify the point. Velvet and chenille are not interchangeable. Velvet is a weaving technique, dense and uniform. Chenille begins in spinning, as a constructed yarn with a pile—short or long—that produces surface variation once woven. Chenille introduces marbling. Velvet remains compact. The distinction matters. Milan does not blur processes.

Both materials are shifting. They respond to light. So does rain. Milan was once defined by constant rainfall. Now even that has become an object of nostalgia. The word “cangiante” – iridescent – captures the collection, but also the city itself: a January day, low clouds, muted light filtering into an apartment where shadow is not avoided but welcomed. Rain alters blues and greens. Fabric behaves the same way. Soft trousers move like veils; their folds resist the rigid geometry of classical tailoring while remaining technically precise. This is not softness as weakness, but as control.

Iridescent is the color, the surface, the attitude. The term iridescent describes Milan’s temperament and its restrained irony. The irony is not defensive; it is functional. It is what allows the city—and Armani with it—to move beyond nostalgia without denying it. What remains is clarity, discipline, and an undeniable sensual charge.

Carlo Mazzoni