How local ecosystems are risking collapse under the fishing industry – Lampoon investigates interviewing local fishermen on the Spanish island

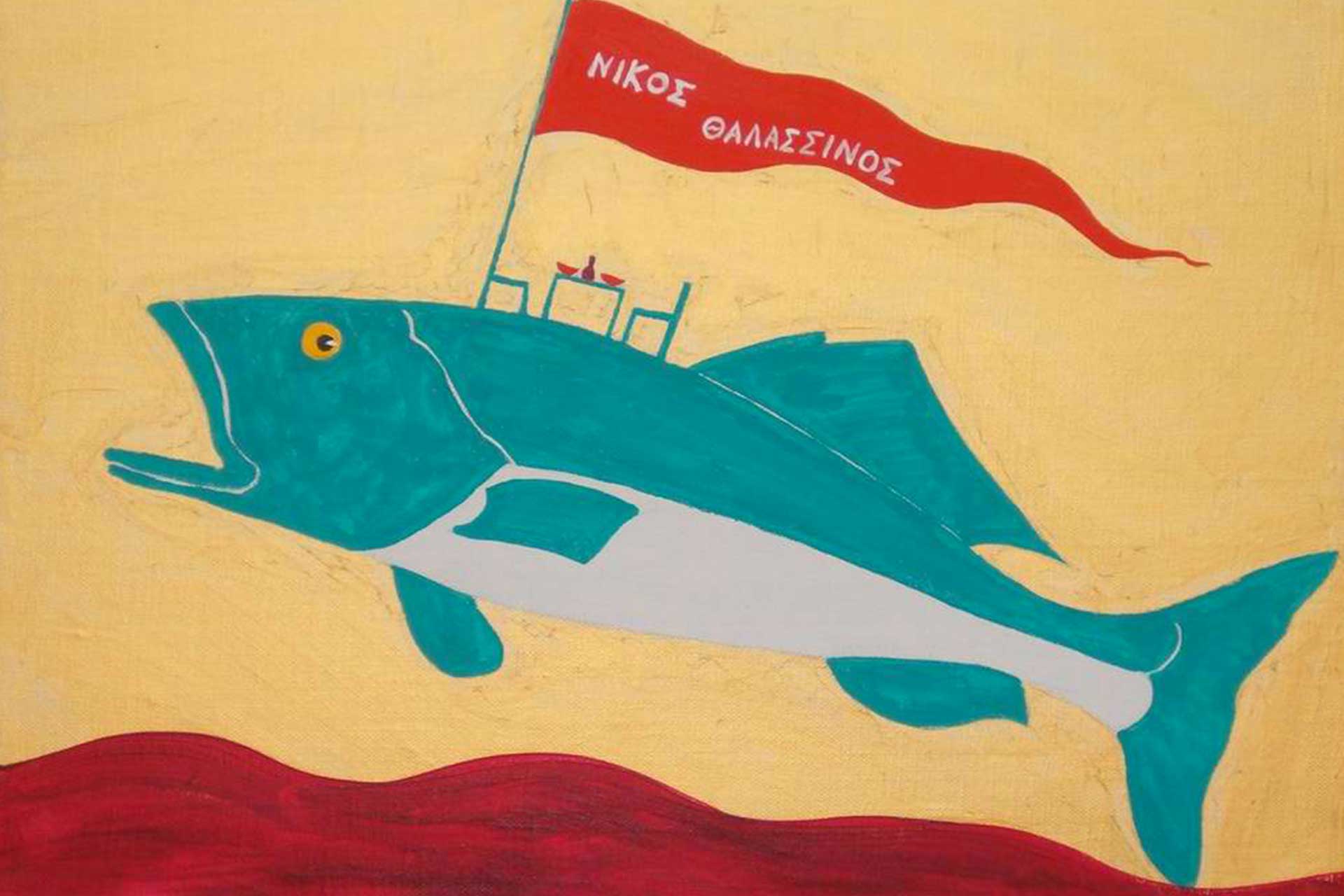

Seaspiracy: Truth or Tales?

The documentary Seaspiracy shot by Ali and Lucy Tabrizi hit Netflix’s top ten both in the US and the UK, sparking widespread debates about the information it presented. While many acclaimed the facts outlined by the documentary, some focused on its shortcomings. The documentary was accused of being sensationalistic and faced criticism on two main points: that the oceans would be virtually empty of fish within 2048 if business continues as usual and that sustainably caught fish does not exist. Seaspiracy’s conclusion is a call to action: that one stop eating fish – including farmed fish which contributes to the problem.

Lanzarote Fish Farming

To investigate the veracity of these claims one can take a closer look at any of the many fish farms across Europe where similar dynamics play in a never-ending loop. On the Spanish island of Lanzarote sits a fish farm operated by Yaizatun SA, part of the larger group Ricardo Fuentes e Hijos. Located in Playa Quemada, the farm produces Lubina (Sea-bass) and Dorada (Sea-bream). In total each year around 2,000 tonnes of fish are sold to national and international markets generating lucrative returns. Playa Quemada is described in guide books as a small fisherman’s village.

Today little trace is left of this tradition. Upon arrival the bay seems empty, with only one fishing boat moored in front of the village, while the other fishing vessels sit ashore in a state of abandonment. Looking out to sea one can see the pens and the many boats that navigate between the bay and Arrecife, the capital of Lanzarote. The marine traffic between Arrecife and Playa Quemada is due to the new fish packaging plant set up in Puerto de Naos, Arrecife’s central port. Here, Ricardo Fuentes e Hijos is expanding their fish packaging plants thanks to large grants by the European and Maritime Fisheries Fund: in 2017 alone 1.175.686 euros were invested in the project.

The Playa Quemada fish farm has contributed to sustaining Lanzarote’s fishing industry as the large plants in Arrecife depend on the steady flow of farmed fish to remain in business, as wild caught fish stocks are rapidly declining. Fish farming is often presented as a sustainable alternative to consuming wild caught fish: because farmed fish is not part of the wild ecosystem, eating it will not cause global fishing stocks to plummet. Farmed fish are actually fattened up with fish-feed composed mainly of wild caught fish. This is because farmed fish does not reach its desired weight on a plant based diet alone. The farms in Playa Quemada use the brand DIBAQ which uses three oils in their range of feeds: came line oil, fish oil and Norwegian salmon oil, displaying how a high number of wild-caught fish are necessary to produce their farmed counterparts.

Lanzarote tuna industry

The island of Lanzarote is home to a second lucrative fish business. Other than farming Dorada and Lubina, the island catches high quantities of Blue Fin Tuna which is considered an endangered species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Located in Arrecife is Optuna n42, a tuna producer association which was created to safeguard the future of the industry and to improve the commercialization of its member’s tuna catches. Optuna’s annual revenue is 4.57 million USD which is divided amongst owners of the fishing boats.

An industrial fisherman who wishes to stay anonymous says: «on Thursday we caught forty-eight Blue Fin Tuna on the Cima de Oro but we gave ten to another boat: this is for commercial purposes because you can only submit a certain number of tuna per day. Because of this, they (Optuna) have formed a cooperative and pass each other the fish». The tuna is caught using 600m lines and is pulled up by hand by members of the crew. The anonymous fisherman continues «I had never been working in a fishing ship. In my town we sometimes go fishing for fun with small poles – but not working like that, in those conditions. They are not humans, they are animals. They are 40/50 year old alcoholic men, working everyday twenty hours. They are strong. I couldn’t do it, I was there for one month and I am dead – not physically but psychologically».

The subject talks about the inhumane conditions aboard the industrial fishing vessels: «Imagine working twenty hours every day and you might not have a finger anymore. One of my friends – he doesn’t have an eye. He has a glass eye. One week ago another lost a part of his finger in the machines. He lost it and I was there with him». Due to the bad pay and the harsh conditions on board the subject has chosen to quit his job and find work elsewhere, however this is a common sentiment: «It is difficult to be a long time of your life in that job. They do not have many people that want to work there. Usually they depend on people from Senegal, from Morocco». The subject concludes: «The price of tuna is like the price of gold because each year there are less and less. We sell our tuna in Japan – they pay better». This comment displays how the scarcity of tuna is what causes its value: on certain markets Blue Fin Tuna flesh is equal or even superior to the cost of gold.

Lampoon review: Lanzarote local perspectives

These large industries have had equally large impacts upon local livelihoods and ecosystems in Lanzarote, and today Arrecife’s central fish market the Pescaderia Municipal is almost empty as a result. The Pescaderia only sells locally caught fish, and while once a vibrant hotspot, today only one of its seven booths is open for business. Marciano, a local fisherman who has been working in Lanzarote for seventy-seven years bears witness to the fact that ten years ago the Pescadoria was full.

Five years ago, only two bancos remained, while in 2021 only one was open. Pedro, another local fisherman with thirty-five years of experience claims that this is a result of both fish farming and industrial fishing in the area. Pedro states that industrial fisheries are funded by the government, and claims that they intimidate small scale fishermen not allowing them to fish in the area. The larger cause appears to be the fish farming or pesce-factoria in Playa Quemada. Marciano adds: «the fish farm is fatal for the fisherman and for the fish».

Both Pedro and Marciano see the pesce-factoria as the main cause for the decrease in wild caught fish in the area. The feces produced by the farm provokes changes in the quality of the seabed which is where wild stock reproduces. The species bred in the pesce-factoria are predators which are non-native to the area: fish which manage to escape the pens eat smaller specimens which does not allow the food chain to replenish itself. Due to the impacts of fish-farming and the large scale fishing industry, local fishermen like Pedro and Marciano have been forced to capture smaller and smaller juvenile fish to try and make a living. This causes further collapse of local ecosystems as the few surviving wild fish are unable to reach reproductive age and replenish dwindling stocks.

Legislation and Overfunding

The issues caused by fish farming and industrial fishing in Lanzarote can be traced to a lack of efficient legislature. Spain is divided into various Autonomous Communities to which the central government devolves a certain degree of power to allow for increased regional governance. According to the FAO Fishery legal framework for Spain: «the Autonomous Communities exert exclusive competence in inland waters, harvesting of shellfish, aquaculture, hunting and riverine fisheries», meaning that each autonomous community can make their own laws in regards to the fishing industry.

More often than not, these legislations are in favor of economic exploitation of marine resources rather than their protection and replenishment and are frequently subject to greenwashing. This relaxed form of governance is further exacerbated by the fact that the European Union provides large sums of money to further develop this badly regulated industry. In 2020 the total available budget allocated to fishery grants was 6.4 billion euros, with Spain receiving 19.55% of the total – by far the largest sum. Each member state is required to spend 26% to develop sustainable fisheries, 20% to the development of aquaculture, and 19% is used to implement the Common Fisheries Policy – a set of guidelines for managing European wild fish stocks.

The coupling of limited laws and overfunding can lead to illicit behavior, and in 2018 Operation Tarantelo uncovered an illegal Blue Fin Tuna racket operating between Spain and Malta worth 12 million USD. The Spanish group Ricardo Fuentes e Hijos was heavily implicated and owned the two ends of the smuggling routes. Illegally caught tuna was being farmed in fish farms off the coast of Malta, from where it was transported to Spain moving through France and Italy. Although the EU has some of the most stringent regulations in place to avoid overfishing, a report by the National Audit Office published in 2018 claimed the CFP enforcement unit was understaffed by a tally of 65 people and was subject to frequent resignations, causing one to wonder where EU funds go.

Local governments had been unable to fill the positions. Seaspiracy may have inflated statistics to increase its impact upon wider audiences; as a result of taking a closer look at the fishing industries in Lanzarote, it appears that most of the points covered in the documentary were true. Farmed fish depend on wild fish in the form of feed and heavily degrade local ecosystems, while both industrial and local fishing is exerting increasing pressure on wild caught fish causing ecosystem collapse. What is saddening is that these industries are funded by European taxpayers money and if change does not happen soon, perhaps Seaspiracy’s thesis will not be so far from the truth.

Seaspiracy

Is a 2021 documentary film about the environmental impact of fishing directed by and starring Ali Tabrizi, a British filmmaker. The film premiered on Netflix globally in March 2021 and garnered immediate attention in several countries.