How do you construct your work? Working Drawings provides an insight into the question. «I have tried to show as far as possible by what means I have found my way as a painter»

Working Drawings: the working process

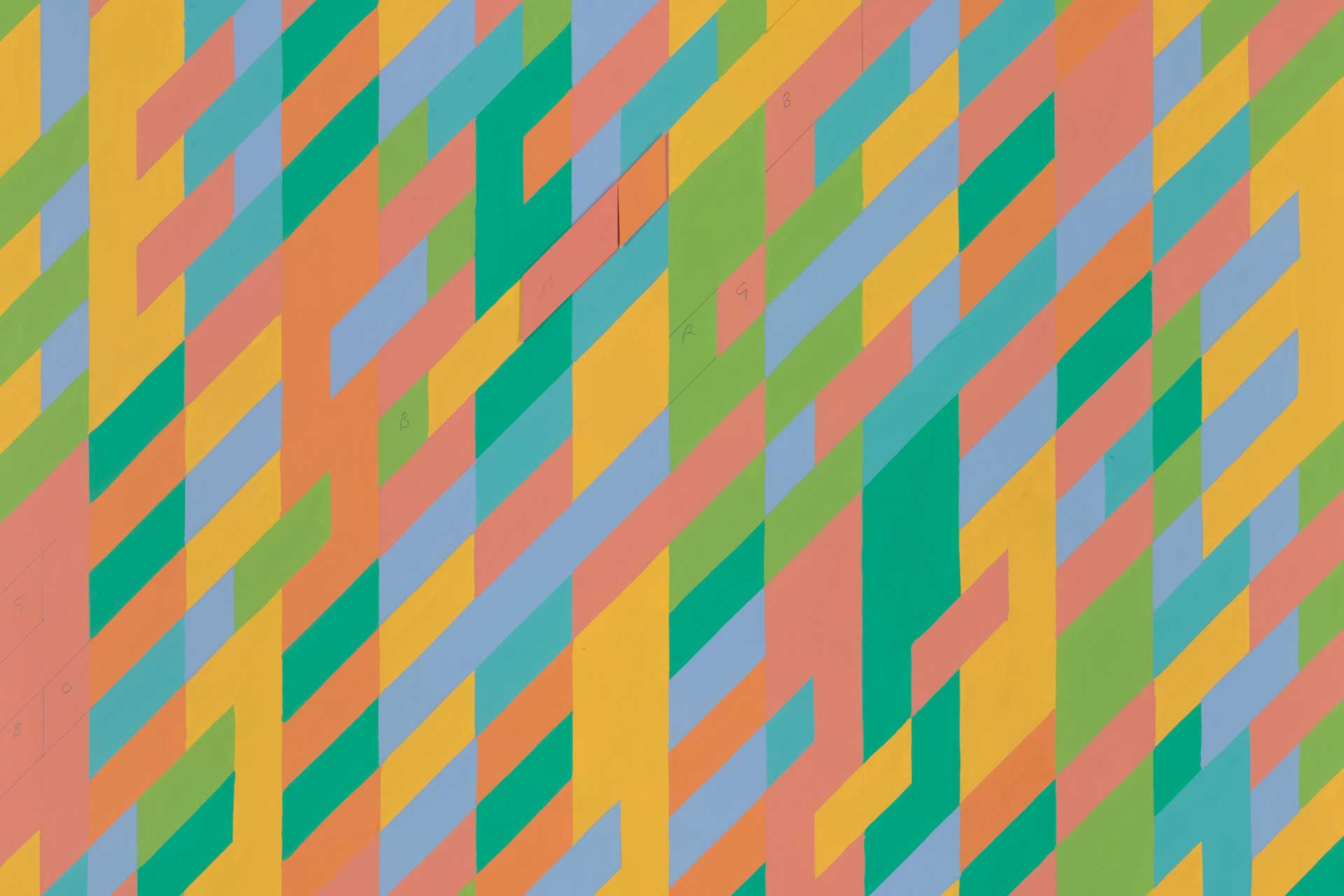

Bridget Riley is an English painter born in Norwood, London in 1931. Known for her op art drawings and paintings. A term used to describe an art movement in the 1960s which used geometric practices to create optical effects. The movement has various forms: from a subtle use to a distorting and falsifying application. Riley, along with artists such as Jesus Rafael Soto and Victor Vaserely were pioneers of this style of work.

Riley’s book, Working Drawings, came out in September 2021. Is the first of her book on her preparatory work. Described as a «core collection» of her work of both studies and drawings still within the process.

Riley gives readers a look into how her paintings, thought about and then brought to life. As a gateway into her artistic process, Bridget Riley imparts of what impelled her to reveal such processes in the foreword to the book. She writes, «I discovered at an early age that this question concerned many visitors to my exhibitions. I have tried to show as far as possible; by what means I have found my way as a painter and some of the steps I have taken». Spanning over 150 pieces of work, the book traces the life of Riley as an artist. The evolution of her work as a revolving process is a parallel to her own and life working as an artist in the studio.

Bridget Riley’s early life growing up

Riley’s spent her childhood between Cornwall and Lincolnshire and in 1949, she went to study at Goldsmiths College in London; her aunt had also been a student there. Following this, she then studied at the Royal College of Art. Riley learnt at Goldsmiths until 1952, a formative time in which in the catalogue, Bridgit Riley: From Life. She talks about her first term at Goldsmiths; describing a feeling of angst and frustration. «I had arrived anxious to make a start. To find a firm basis for the work that I hoped lay ahead». Arriving at University in the aftermaths of World War II; she describes her sentience of privilege to be in position to study art in such an unstable economic time. Acknowledging people older than her, who, after leaving the active service of fighting during the war; were likewise going to study art. «Coming straight from school, I counted myself lucky to be there», she says.

Riley’s education into art: far from unusual

She regards the training which she had as «very important», forming her foundational skills in drawing and painting. Art school raised the importance of analysing the subject and how to use the light-dark scale to establish pictorial spaces. She explains that in her life drawing classes with her teacher, Sam Rabin; he questioned his students to ask, «What is the model doing?». Following their answers, he would question again with why; emphasising the fundamentals to think of when drawing a human figure standing. The subject means deliberating all the parts of the body; manoeuvred and positioned to allow that motion to happen. «One has to work to full consciousness» she says.

Seemingly for Riley, her words on the time of settling into art school suggest she had spent time contemplating what it means as an artist to question the process. Was she looking for a distinction of her own work? Or perhaps something which moved away from the traditions of painting as she currently understood it then. The art which had dominated the 1940s was abstract expressionism which centred mainly in New York. The 1940s was a time of change worldwide, relics and reminders of the Great Depression. An ongoing World War II and the onset of the Cold War. Riley looked for where to start. She writes, «To begin at the beginning, that would surely be the best start of all».

Evacuation in WWII

In conversation with John Leighton, a British art historian, Leighton asks Riley about how as an artist to see things foremost before drawing is her origin of her conception of art itself. Describing the time when her and her family were evacuated from Lincolnshire to Cornwall. «In the morning, I awoke to a completely new world, different in every way». For Riley, Cornwall held immense beauty and nature. They spent many hours walking the trails of beaches, farms and cliffsides and Riley found solace in looking at the views from around her. «Looking became more than pleasure, it became a way of life» she said.

The displacement and upheaval of being evacuated wasn’t all bad. Being in a place of serenity and calm. Away from the war meant being absent from the noise and the horror in a physical sense, but its presence was still there. Riley writes, «That summer was one of the most beautiful ever recorded. There was something unearthly about being on the verge of hostilities, and having one radiant day after another». Abstract expressionism’s unconventional and less tradition style during the 40s is often attributed to this time; in which death and war continued to evoked feelings of nihilism. In this type of art, subjects are often distorted and indistinguishable. The lack of observed precision is recognised as a manifestation of the horrors; that were taking place in life at that time, a mere reaction to how bloodshed can be explored and experienced.

Tracing the lineage

Riley’s visits to the Prints and Drawing Room at the British Museum which held the drawings of many Renaissance artists provided much of her own insights into her work today. «It was thrilling and inspiring to see at first hand the drawings by great Renaissance artists and to realise how many of their insights were still, five centuries later, critical to my own endeavour» she writes. Tracing the lineage of art history arises itself as significant work for any artist who wishes to begin to place their own work among the people before them.

By finding a small kernel of relation or similarity it seems to bring a grounded feeling for an artist who is figuring out where their work belongs. Riley describes knowing of Matisse’s work from a very early stage of her career as well as Edward Munch, who herself and her friend Gerald had studied closely whilst she was at Goldsmiths. She also engaged with the artist, Georges Seurat, a French post-impressionist artist who devised informative painting techniques. Writing on him in her essay, Seurat as a Mentor.

The influence of many artists on Bridget Riley

Riley says, «It was Seurat’s painting that first drew me because, after they taught me to draw extensively, I felt at a loss in approaching colour. From his work I learnt something about the interrelationship of colour and tone as well as the advantages and limits of a strictly methodological approach». Many artists at the time inspired her. But it was formal qualities of their work which appealed to her in an initial sense. She says, «I believe that if one continues to be faithful to one’s work, a credo or philosophy will emerge».

Through figure drawing in her life classes, Riley worked to form her own artistic style. She notices the details; the outlines of the subject, how they move whilst posing, their substance or dexterity and the chiaroscuro effect on how their overall shape resembled. Riley seems to find a way to look at all the parts without losing sight of having an overall perspective, she writes, «But the most important thing was to retain the first impression of the whole».

Communicating with op art

When looking through the pages of Working Drawings, Riley’s work emphasises the complexity of us as individuals and the vulnerability of us all. Her subjects are never the same. Nor she idolises or denigrates a particular body or shape. The creases, rolls, and crevices of the bodies are what tells them apart from one another and what gives them their sensitivity and look of being alive.

Curator, Lucy Askew, writes in her piece in the book, Ordering the Ground, of how she identifies the approach Riley to her work. Storying the making of her as a wide-ranging and broadly exhibited artist. Askew portrays her as someone devoted to detail; and the analytical development of her work. Refusing to lapse into a mode of insularity, Riley’s work shows a consideration of colour, form, composition, and style, abetted by the memory bank she has collected with her eyes.

Riley’s work is inclusive

Askew describes how Bridget Riley’s work is inclusive in a dialectical sense using what is seen and heard to create art which evokes emotion through the organised use of lines and their direction. She describes how Riley would write down her observations, encouraged by her teacher, Rabin, who raised the importance of focusing on what the subject was doing. Annotating bits of paper, Riley would write, «the landscape is ‘dominated by white’, there is ‘tonal equality’ a ‘close and limited tonal range’ and ‘Sandy dominated harmony’». To write about drawing is to connect the relationship between the two enabling the words to give an ability to analyse, reflect and critique. Riley has been known for her notes accompanying her work, Askew noting how they «appear as aides-memoires, directions for painting assistants, or to provide explanation».

Bridget Riley

Bridget Riley is a British artist. Riley studied at Goldsmiths College and The Royal College of Art in London. She began teaching art and working as an illustrator for J. Walter Thompson in the late 1950s. Riley’s early paintings were primarily landscapes influenced by Impressionism and Pointillism. The artist started experimenting with optical effects in 1960, leading to the emergence of Op art several years later. She also discovered the black-and-white paintings of Victor Vasarely. Her recognition of the International Prize for Painting was the first for a woman at the Venice Biennale, 1968. Riley, now 90 years old, lives and works in London.