With similarities to Joan Didion, I Fear My Pain Interests You examines issues of power, how it is or is not inherited, what the consequences of being defined by others are, and the ways pain shapes us

Stephanie LaCava on Daily Life

Stephanie LaCava writes about people, interactions, sensations and behaviors. Her previous novel, The Superrationals, is a satire explorative work of fiction which delves into the tropes of people in the literary and art worlds. With some similarities to this novel, I Fear My Pain Interests You, both texts illustrate her observation about the peculiarities of the world and its inhabitants.

LaCava’s writing is grounded in looking at the world and trying to make sense of it, her everyday actions informing her work. «A part of honing your skill is the ability to create these witticisms, even in text messaging, if it’s worth anything, since I hate text messaging» she says. She speaks about the way she interacts with her friend over text, trading messages for more than just communicating, but for the act of exploring words and meanings through what is a mundane task.

Each chapter in the novel has the same effect. She says, «It’s a bit exhausting right? Because everything is always working. I’m out in the world and that’s part of being a writer. Part of me and my work, so much of it is psychological, so much of it is behavioral».

I Fear My Pain Interests You – generational similarities

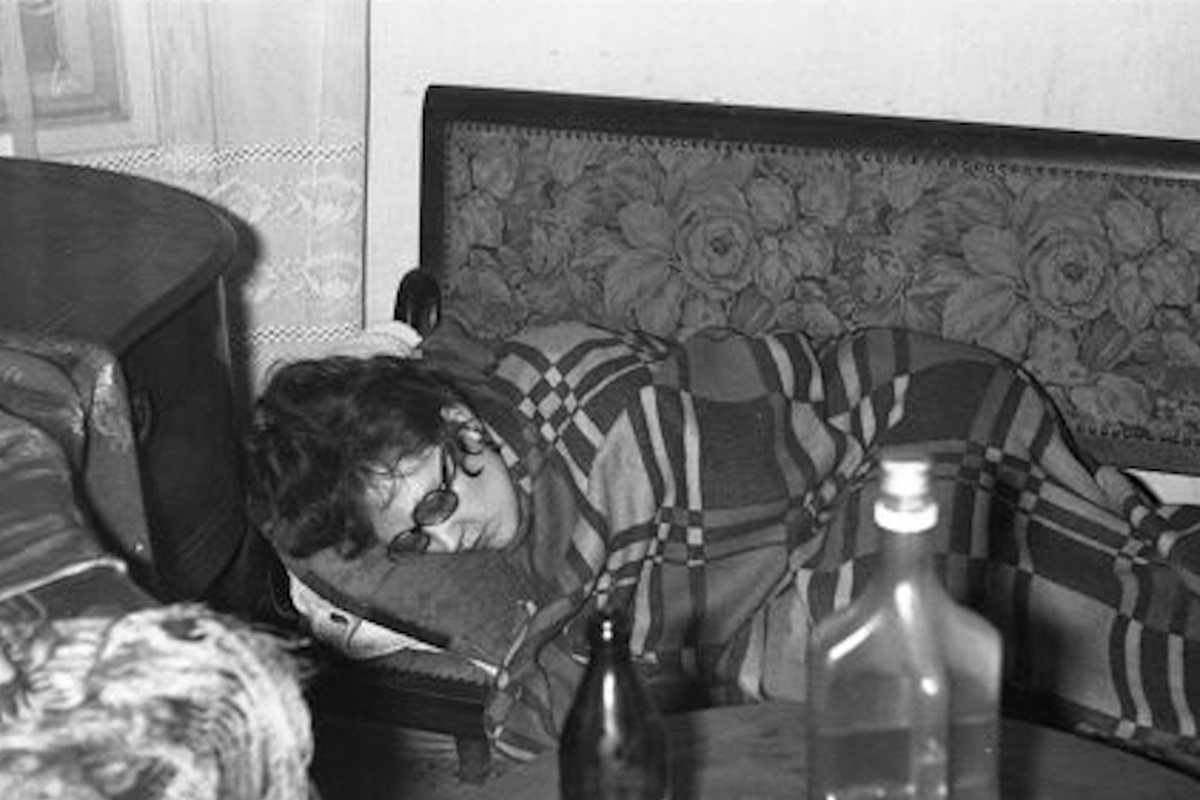

Margot Highsmith, twenty years old, is the distanced narrator who takes the reader through a chaotic, but not abnormal stage of her life. Growing up as the daughter of a famous anarcho-punk musician couple in the counterculture era, Margot’s world is inhabited by the arts, movies, music and a looming culture of the past. There are cultural references and moments which span decades, throughout the book. It is ambiguous for the reader whether it is imagined to be then or now. «Signifiers have always been a thing for me, playing with them. There are some almost-anachronisms throughout the book: visor-mask, plastic straw, landlines. All the 60s/70s,80s music and films as seen through both the parents and their children: the culture industries across decades and generations» LaCava says.

Hopeful regeneration

The novel begins in the sky, Margot is on an airplane from New York to the North Western outback of Montana after a break up from the Director, a 57 year old whose abusive tendencies towards Margot map what is a focus throughout; neglect and abandonment. On the surface some would say the book is sad. Doomed and paradigm for perhaps all that is wrong in the world. On the other hand, filled with cultural references and a subtle political stance, I Fear My Pain Interests You presents the reader with ideas to question. This in some ways, does feel hopeful, like the creation of any form of art. LaCava says, «There is this starfish thing to the story; this idea of hopeful regeneration». She recounts someone who remarks on this full circle feeling to the book; the way it begins in the sky; an abstract place we can go through but not really say we have been. To the end, where Margot and Lucy are in the graveyard in Montana.

Trading pain for experiences

As the child of famed punk non-conformists, there’s an expectation placed on Margot to do something more than just live her life. Experience, however dysfunctional and unstable, can be used as material to work with. Trade your pain to create something real. Talking about her Grandmother, Josephine, LaCava writes, «She told me to stay with a friend, have experiences, turn them into good work». She continues, «Somehow she thought this short term abandonment would help my art». This narrative around how we can use and explore pain in the story, presents characters as void of empathy. Like Margot’s relationship to the Director and then Graves, her pain or lack of it, is the driving force of what sustains their relations; «graves idealized me in my disorder» LaCava writes. What does it mean to commodify pain and suffering? The neoliberal attitudes to pain being treated by therapy, an individual endeavor you can pursue to get better, if you have the means.

‘You, Me, I’ context

The culture industry and individualism are skewered in the book, as all characters around Margot, aside from Lucy, show only concern for themselves. There is a lack of morality in the pursuit of artistic, intellectual aims or, in everyday situations, presenting a world depicting people who are out for themselves. When Margot is bleeding on the flight to Montana, LaCava describes an interaction between Margot and a stranger. Referring to the bleeding bottom lip, the woman says «lady, you should deal with that» – a microcosmo for the way dealing with personal problems is framed in our culture now: within a You, Me, I context.

Margot’s relationship to the Director looks at the extent to which individuals have the ability to emotionally abuse others, in this case in a heterosexual relationship. LaCava cites, «I knew the Director had the ability to put blinders inside his head cavity». «He didn’t evolve, you adapted». Like Graves, the male characters in the story are presented as self invested. Lucy proves the only character who acts with care to Margot and looks out for her throughout. LaCava comments on female friendships, stating that «my books are often about the sustaining force in female relationships, as fucked up as they are».

Capitalism, Resistance, Care and Kindness

In an early part of the novel, Margot remembers a conversation as a child with her father about music, Margot says «I don’t listen to backpack music». She exclaims how she won’t wear merchandise of someone famous enough to be on a backpack; she makes a point of wanting to seek out the less well known, the unconventional. In a conversation between friends of Rose’s, someone says, «Pop stars shape shift all the time, online, everywhere. People can’t match reality. Bad business. Mass appeal». To sell out, is to succumb to it all, to give in to popular culture.

In a world where political action can feel ineffective, cultural criticism seems like the only form of resistance. In the inter-war period, a school of social theory and critical philosophy – the Frankfurt School, wrote ideas about how they were cautious of what they understood as the ‘totally administered society’ – the increasing power of capitalism over all aspects of social life, including the culture industry. Seemingly, at that time, they thought that affirming individuality seemed like the only response to the threat of society becoming one dimensional. Individuality is the world we live in, yet it doesn’t create a society which fosters the things needed: like care or kindness. LaCava says, «A lot of us live with compromises and contradictions in the system as it is. That’s not asking for a pass, rather acknowledging something my writing tries to do, as well: Show this. Present it. Then, feel or think whatever you want of it».

Anarcho-punk

The theme of anarcho-punk is a constant through the book; the references to Margot’s family’s legacy, punk-music and Margot’s discovery, towards the end of the novel of the 1968 Cannes Film Festival in a box in the garage at Lucy’s house. These things add to this idea of resistance, control, power. «There are fun things with it too; like, the anarchist political activist and writer, Emma Goldman’s address is the address where Margot lives in New York». Like Didion’s work, LaCava’s unraveling of the themes in the book are developed through her detail of the minor things; Margot’s interactions with strangers, the body horror and childhood memories with her Mother or Father. «It’s about the small things, about human interactions and human emotions. Thinking about what they magnify to us without making any grand statements». LaCava’s argument isn’t stated in her writing, yet the critique of how we live is whispered through the narrative.

All she wants is consistency

LaCava’s writing and tone has similarities to Joan Didion. She writes, «Not accountable for connection. Sit back and wait. Not ending or beginning anything. If both are ruled out, possibility–everyone is always in play». There is attention to how things feel, sensations at any given moment that make the writing seem like an internal monologue of Margot’s, while retaining an aloofness to her character. «After I threw up and went to the back window, I saw his ashes in the baby-blue porcelain dish. I looked at my phone again. No message. It was nearing ten o’clock. I pushed the ashtray off the sill and watched it smash below». The short sentences, ellipses and questions create an erratic and sometimes franticness to the work. Nonetheless, in suffering, Margot somehow remains relevant «all she wants is consistency».

Stephanie LaCava

Writer based in New York City. Her work has appeared in Harper’s, Artforum, Texte zur Kunst, the New York Times, the New York Review of Books, Vogue, and Interview. Her debut novel, The Superrationals, was published by Semiotext(e) in 2020.