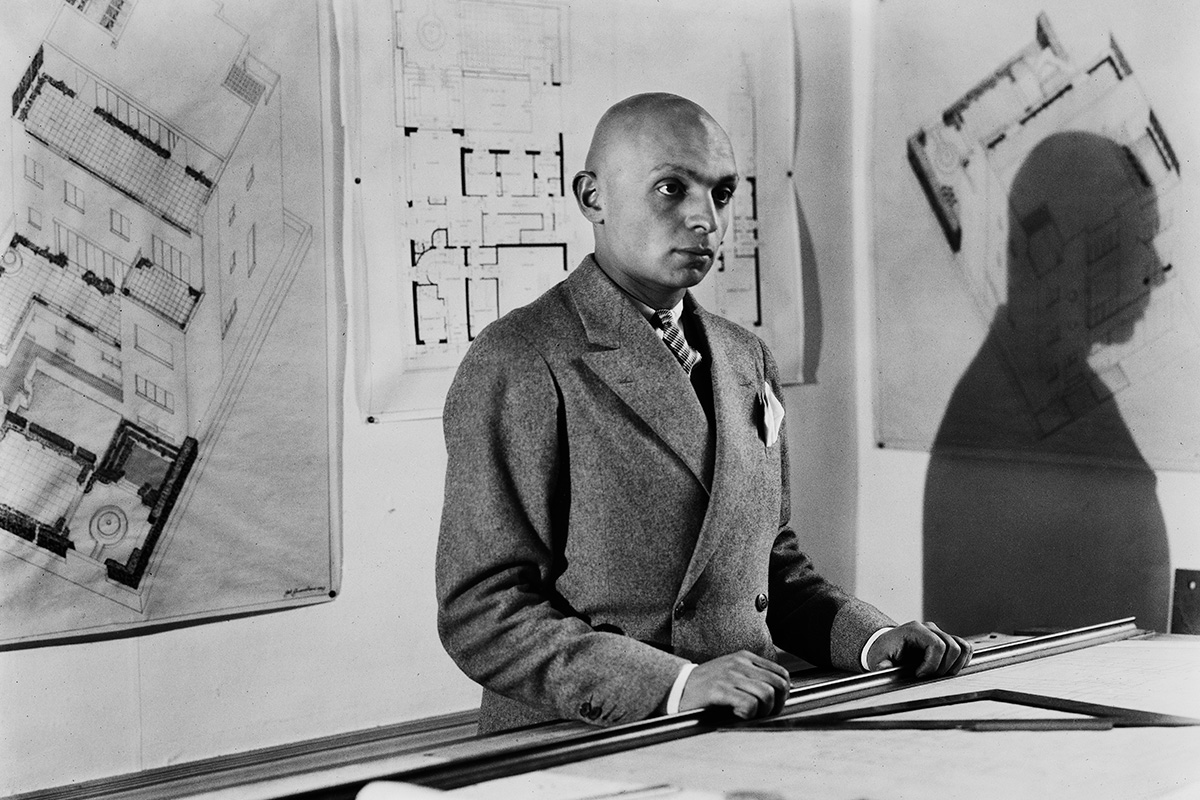

The lithe social muscle of an early freelancer: «As a reader and later as a writer of his character, it was not difficult to imagine [Gabriel Guevrekian] in Gertrude Stein’s house or in a poetry session with Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald»

The Multiple Lives of Gabriel Guevrekian

In his seminal work, Menschliches, Allzumenschliches (E.W. Fritzsch, 1878), German philosopher Friedrich Nietzche wrote: If a man 80,000 years old were conceivable, his character would in fact be absolutely variable, so that out of him little by little an abundance of different individuals would develop.

First published as The Multiple Lives of Gabriel Guevrekian (AA Files No. 71, 2015), an article in which Hamed Khosravi singled out thirteen distinct personae, The Elusive Modernist (Hatje Cantz, 2020) represents the culmination of Khosravi’s systematic and fact-driven post-doctoral research project on Gabriel Guevrekian (1900-1970), which references archival material from forty archives and libraries across thirteen countries.

Despite Guevrekian’s life spanning only seven decades (in comparison to Nietzche’s fictional man 80,000 years old), Khosravi documents the way in which, enabled by the deftness of his social muscle, out of this singular protagonist of the Modern Movement developed twenty personae or modern identities.

Twenty Personae, Twenty Chapters

«It was a challenge to design the book as a document, as a narrative if you like. I spent at least two years just thinking about how to write about this character, because what are discussed as facts and evidence in the book are very scattered», begins Khosravi. Separating The Elusive Modernist into twenty chapters or micro-narratives — Armenian Émigré, Academy Fellow, Family Man, Iranian Socialite, Parisian Radical, Persian Garden Designer, Fashion Lover, Obscured Pioneer, Austrian Interior Designer, UAM Ambassador, Active Publisher, Secretary General, Viennese Modernist, Tehran City Architect, Anarchist Partisan, French Military Urbanist, Nomadic Avant-Garde, American Professor, Eminent Master, and Postcard Collector — Khosravi acknowledges and, to some extent, exaggerates these personae, while challenging the chronological order of the book. «It gave me the flexibility not to follow a linear narrative and therefore not to stick to the framework of a monograph which starts with the birth and ends with the death», he explains.

Borrowing from Cinematic Editing, Methodologies and Techniques

Focusing on those personae most closely associated with Guevrekian’s lithe social muscle, Khosravi explores how this technique borrowed from «cinematic editing, methodologies and techniques in order to give each life it’s own independent character and, at the same time, lead them formally, conceptually or temporally to the meta-narrative or grand narrative of the book».

Here, Khosravi points to the Nineties films of his youth that came to inspire the structure of the book: from The Double Life of Veronique (1991) directed by Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieslowski, which tells the story of two identical but unrelated women and inspired the title of his 2015 article; to Four Rooms (1995), which was directed thanks to the combined efforts of American filmmakers Allison Anders, Alexandre Rockwell, Robert Rodriguez, and the debut film of Quentin Tarantino; and Run Lola Run (1998) directed by German filmmaker, producer, screenwriter, and composer Tom Tykwer, which proposes three alternative outcomes that hang on a minor event along Lola’s run.

The Armenian Émigré

In the opening chapter of the book, Khosravi presents Gabriel Guevrekian as Armenian Émigré. Born in Constantinople to Armenian parents in 1900, through Armenian Émigré Khosravi contextualizes the way in which, as an infant, Gabriel’s family was forced to flee the Ottoman Empire. Scattered to the winds in one afternoon, Khosravi writes how Gabriel’s family dispersed from Tehran to Mumbai, Philadelphia, Vienna and Marseilles.

The Family Man

Imbued with both great tragedy and favor, it is through Family Man that Khosravi examines the extraordinary nature of Gabriel’s childhood and how it was thanks to Gabriel’s father — a successful merchant with enterprizes extending from Armenia and the Ottoman Empire, to Persia and Europe — that Gabriel’s nuclear family came to reside in Tehran and into contact with the city’s aristocratic, cultural and intellectual elite.

«Iran is a specific case amongst the neighbouring countries of the Ottoman Empire, because there has been a very close relationship between Armenia and Iran throughout history. There are mixed ethnic groups, mixed cities, which are Armenian — although proportionally or statistically they are a minority, they are the heart of the social life of any community, especially the intellectual community, writers, cinematographers and so on», he explains.

In deed, during the rule of Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar (reign: 1896-1907), Gabriel’s father was appointed as Registrar of the Royal Treasury and would become the first person to list and value the royal jewelry of the Qajar dynasty (1779–1924): a historical diamond collection of such rarity that, today, the national treasury use the crown jewels as a reserve for their currency. Even after the death of Mozaffar ad-Din Shah, Gabriel’s father maintained his working relationship with the Government of Iran and later settled in Northern Tehran in a large mansion located at 3 Nobahar, where Gabriel would spend his early childhood. The property with an immensely huge pool was almost one full city block and the mansion had numerous rooms and also underground living quarters, remember Marina and Simon Guevrekian — Gabriel’s niece and nephew — in an excerpt from their 2018 interview with Khosravi.

It is also through Family Man that Khosravi details how Gabriel and his older sister, Lyda, were sent to Vienna in 1910. While Lyda trained as a pianist, a young Gabriel first trained as a violinist at the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Conservatory of the Society of Music Lovers). However, after coming to terms with the fact that he would never be a virtuoso, it was at the Kunstgewerbeschule (Academy of Applied Arts) that he would go on to train as an architect under the direction of Austrian architects Oskar Strnad, Josef Frank, and Josef Hoffmann. After graduating, Guevrekian — along with fellow student and lifelong companion, Hans Vetter — would go on to work for the offices of Strnad and Hoffmann, before moving to Paris to work with French architects Henri Sauvage and Robert Mallet-Stevens in 1922, where Lyda would later join them to marry Vetter in 1924.

The Iranian Socialite

Although their lives would take them on different adventurous paths, these two siblings shared large parts of their lifetimes together: in Tehran, in Vienna and in Paris, writes Khosravi. In the following chapters, he explores how it was in the glittering postwar capital of the arts that Gabriel — as Iranian Socialite — and Lyda became part of the Parisian avant-garde, which at the time included Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Gertrude Stein, and Pablo Picasso (at whose wedding Guevrekian would later be honored as Best Man).

«It’s very difficult to find out whether it was through Lyda that Gabriel came into these circles of writers and artists or the other way around, but they seem to be both very much appreciated at the center of these circles — in Vienna and in Paris», contemplates Khosravi. What is clear, is that their hyper-mobility, command of languages — which included Armenian, Farsi, French, German and English — and bohemian characters made them highly socially attractive people: «Being able to be in Paris and hang out with Americans, at that time, was a matter of language. We know that there were very few American artists then ended up in Paris during the avant-garde movement and they struggled because even the very famous Parisian artists of the time were not able to speak English. Guevrekian was a bridge between the Viennese section, the Parisian, and the American».

Le Deux Magots, Le Select and Dingo American Bar

It is also through Iranian Socialite that Khosravi documents Guevrekian’s social movements in exacting detail: Guevrekian was a night owl. After finishing work — usually 10 p.m. — he would often meet up with friends for dinner at either Les Deux Magots in Saint-Germain-des-Prés or Le Select or the all-night Dingo American Bar in Montparnasse, where the barman was Jimmie Charters, a former lightweight boxer from Liverpool, and where the clientele, in the mid-1920s, included Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Isadora Duncan, reads an excerpt from Guevrekian’s Tribute to a Radical interview with David Hansen, which was originally published in the The Ricker Reader (March Issue, 1966).

A Delightful and Unexpected Pastime — The Weekly Basketball Game

Beyond evenings spent at literary liqueur cafés, Khosravi also reveals a delightful and unexpected pastime — the weekly basketball game played with Le Corbusier and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret. One time forward, the next time guard. We all played all the positions, reads a direct quote from Tribute to a Radical. «As a reader and later a writer of his character, for me it was not difficult to imagine him in Gertrude Stein’s house or in a poetry session with Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, but something that came out as a surprise — a very nice surprise — was the weekly basketball game. To be honest, I didn’t believe it at first», reflects Khosravi. «Even a couple of weeks ago, I found a letter between Guevrekian and Tristan Tzara, the playwright, where he mentioned that he would see Guevrekian in the basketball game on Tuesday and that Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret would be there», he adds.

The Parisian Radical, The Persian Garden Designer and The Austrian Interior Designer

In the central chapters of the book, Khosravi goes on to explore the varied works produced by Guevrekian during his time in Paris. Through Parisian Radical, Khosravi details Guevrekian’s designs for the 16th Salon d’Automne in 1923, which included the Reinforced Concrete Villa and Hotel Touring-Club as conceptual projects.

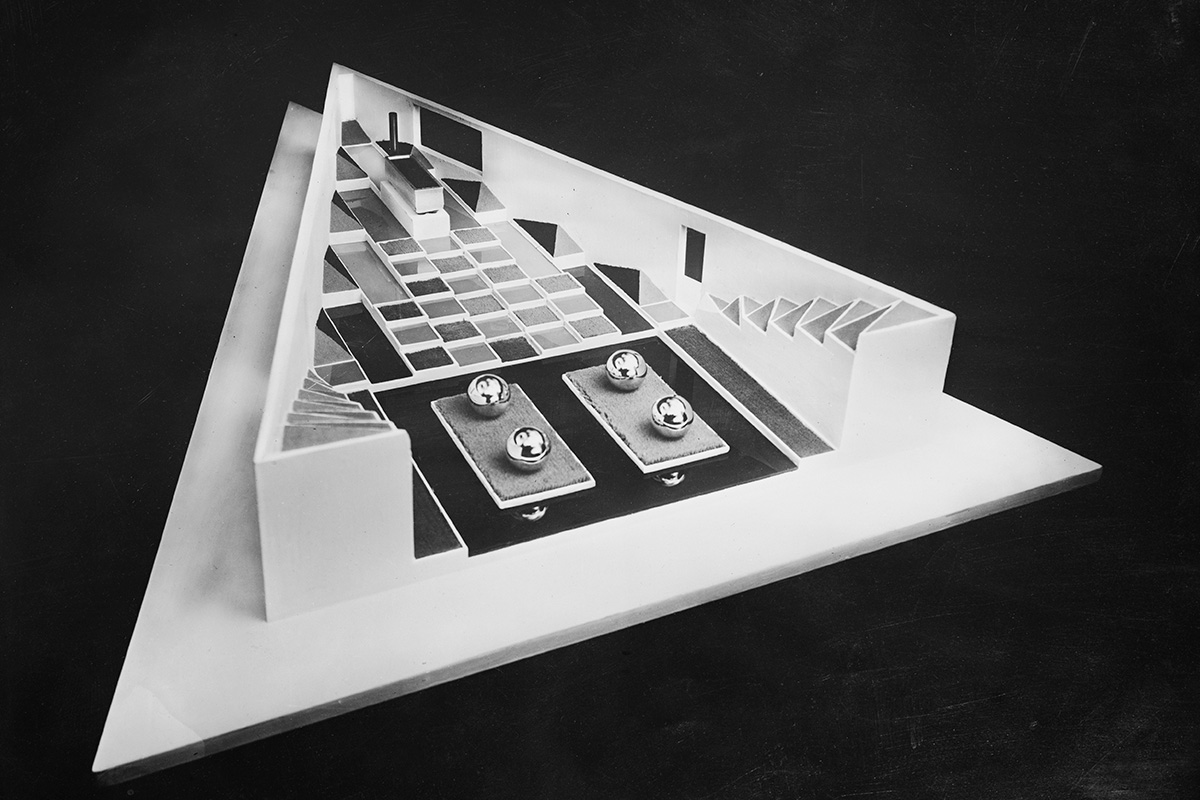

Through Persian Garden Designer, Khosravi details Guevrekian’s design of the Persian garden for the landscape section of the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris. Commissioned by French landscape-architect Jean-Claude Nicholas Forestier, pairs of architects and artists were asked to create ‘instant’ gardens to flank the pavilions (instant because they had to bloom immediately and last for the duration of the fair, which ran from April to October).

For the Exposition, Guevrekian created Jardin d’Eau et de Lumièr: a tiered fountain with a revolving sculpture by French glass artist Louis Barillet, surrounded by triangular patches of flowers and grass in vivid hues of orange, purple, red, and green, and contained within a geometrically patterned wall of pink cement tiles. Attended by Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles, wealthy patrons of the arts who, at the time, were collaborating with Mallet-Stevens on the design of their holiday home in Hyères on the Côte d’Azur, Charles would later write to Mallet-Stevens saying: I very much liked this garden at the Decorative Arts and would gladly ask [Guevrekian] to design one for here, if you think this kind of thing would amuse him. Khosravi writes that Guevrekian — as Persian Garden Designer — was overjoyed to accept this commission, which evolved into the à la mode triangular, checkerboard garden design at Villa Noailles (1926) for which he is still best known today; thanks to the project being featured in the July 1930 issue of the French edition of Vogue.

After opening his own atelier in 1926, through Austrian Interior Designer Khosravi details Guevrekian’s furniture designs. Although his furniture remained almost unknown to the public, Khosravi also writes that among his social circle he was becoming quite famous, with certain pieces of tubular-steel furniture going on to influence Irish-British painter Francis Bacon (1909-1992).

These personae in particular emphasize the deftness of Guevrekian’s social character. «He has been registered as a Turkish architect, Turkish artist, Armenian architect, Armenian artist, Austrian architect and so on. Interestingly, when he moved to Paris he was at first not really accepted into the circle of architects as they were more closed off and because they didn’t want to have an Austrian among them. However, when he was invited to design two houses in Vienna, he was invited back to Vienna as a French architect — so there were all these layers which suggest that he was so much dissolved into the social and even the spatial characters of the places he lived», discusses Khosravi.

The Tehran City Architect

Nevertheless, Khosravi suggests that «from Paris onwards, his movements seem to be much more affected by restrictions, illnesses, conflicts, War and the Economic Depression of 1929». In deed, when the Great Depression took hold in France, many architects began looking for commissions and projects outside of Europe: from Russia to Egypt, Lebanon, South America and the Middle East. In 1933, Guevrekian and his wife would return to Tehran, where he was immediately commissioned the first of twenty private urban villas. Later that year, as part of the Shah’s effort to refashion Iran in a modern image and away from all traces of its Qajar past, the Iranian Government would appoint Guevrekian as Chief Architect of Tehran (1933-37).

Asked to prepare the plans for the city center, the former Qajar Royal Quarter, and the National Garden, it is through Tehran City Architect that Khosravi investigates how Guevrekian drew up a master plan of the city that did not follow the concentric urban form and, preferring to be his own boss, redefined his relationship with the government as an independent contractor. However, in 1937 and before the completion of many of these projects, he was again forced to move due to his wife’s ill health and, as such, no comprehensive archive of his works in Iran exist.

The American Professor

In the closing chapters of the book, Khosravi presents Guevrekian as his final guise, a genial professor in the United States. After living in Saint-Tropez during the War, Guevrekian was prompted to join the exodus of his friends — many of whom were Jewish — in the United States. In 1948, Guevrekian and his wife arrived in Alabama where he would take up a job teaching the Advanced Architectural Design studio of third and fourth years at the Alabama Polytechnic Institute. However, after less than a year in the Deep South, Guevrekian had had enough.

«He’s coming from Europe — he’s coming from Vienna, Paris, London and Tehran. He doesn’t want to live in Alabama», sympathizes Khosravi. In deed, in a letter to American architectural historian and former colleague Turpin Bannister, Guevrekian confided: I want very much… [to be] nearer to an intellectual center. And by the end of the following summer Guevrekian was installed as a professor of Architecture at the University of Illinois.

«It’s interesting to see that it’s not only the architecture that takes him in. In one of his interviews with David Hansen, he mentions that he very much enjoys being at the University of Illinois because he can go to very good orchestra and opera every week and there are really good libraries. In the interview that we had, David Hansen said that the discussion sessions, or even drinking at his place, were almost about music not architecture», muses Khosravi.

A Revolutionary Architectural Pedagogy

Guevrekian’s nomadic life — or rather multiple lives — not only presented him as a man «full of ideas and unknown mysteries», but inspired his revolutionary architectural pedagogy. «This being used to moving and not settling, made him so inventive and innovate in his later years as a professor of architecture», explores Khosravi. «He established the first cross-continental educational programme between the United States and France, the United States and Europe. Heestablished the first joint school with Salzburg and then with Nice in the South of France. And again, going through his correspondence, he was always suggesting nomadic projects: traveling exhibitions, traveling talks and conferences. He knew people in Salzburg, in Vienna, in Paris, in all those cities and he could connect cities and places through this network, not only professionally but in solidarity of friendship».

Guevrekian made every discipline meaningful, every city central, every period epochal, writes Khosravi — for whom Guevrekian remains a key figure for the contemporary role of the architect as writer, practitioner, educator and public intellectual: «It is something that I briefly mention in the introduction of the book, but he is a contemporary figure for me, an early example of a freelancer if you like».

The Personal and Professional Struggles Faced by Modern-Day Architects

In closing, Khosravi makes a point to discuss the personal and professional struggles faced by modern-day architects and what he hopes they can learn from The Elusive Modernist: «I’ll use my own example here, but it’s almost a universal situation of architects finding themselves in such a dilemma between being the bearer of their own intellectual autonomy or serving the industry, the client. This might sound idealistic, but through the shaping of architecture as a profession, architects began to define themselves as intellectuals rather than craftsmen or fieldworkers; they separated themselves from the construction site deliberately. But, instead, it has been almost two centuries of these roles dissolving into one market, with other forms of exploitation. So, if we as architects — as a collective or as individuals — want to preserve some sort of autonomy in our ideas, in our intellectual values, in our intellectual capacities, we face difficult conditions, even when we are teaching in Universities, because these days you have to comply with many regulations and educational frameworks that are purely bureaucratic and reduce ideas into measurable numbers and assets based on the economy of the school. That’s why architectural biennales and triennials are so fashionable, they are escape routes for architects in order to do something that they cannot do in their own offices, in the Universities in which they teach, or even in the books that they write, because even then there is a publisher that measures the content of the book against the market, a very general idea of the market. These events, festivals and exhibitions attract architects and artists looking to preserve their general autonomy, their intellectual autonomy, and, at the same time, fulfil their social task: to talk to people and not have the mediator of the market, the ministry of education, or the client» — a task in which Guevrekian was triumphant.

Hamed Khosravi

Architect, curator, educator and writer. He received his PhD in the history and theory of architecture from the City as a Project program at the Berlage Institute/ TU Delft. He has taught at the Berlage Institute, Oxford Brookes University, TU Delft, and is currently a faculty member at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London.