For Lampoon Issue 27, The RuVido Issue, Photographer Paul Mpagi Sepuya and Dan Rubinstein reflect on looking at bodies in a non-white way, queer representation and the meaning of raw

Lampoon Issue 27: Paul Mpagi Sepuya in conversation with Dan Rubinstein

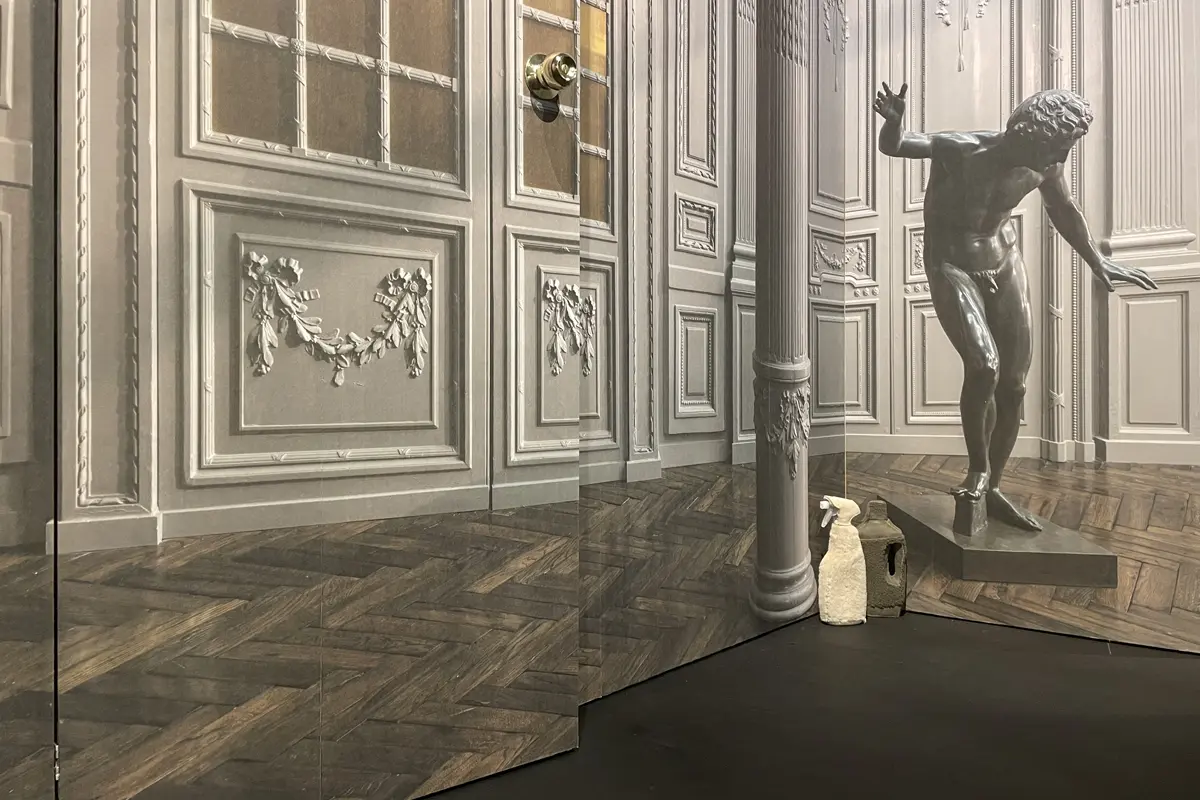

The first time Dan Rubinstein saw the work of Paul Mpagi Sepuya was at the exhibition ‘Being: New Photography 2018’ at New York’s MoMA. The works had a voyeuristic quality. Rubinstein can liken them to a chef who can whip up a meal with just only the most basic ingredients. His work began with portraits taken in people’s homes and evolved into studio portraiture. Some works of his create illusions, like collage, without the aid of a computer, where prints are assembled and photographed using mirrors. Other works are self-portraits or pictures of subjects that appear to celebrate the body and queer identity. Other works have used a photographer’s black shroud to conceal subjects partly or entirely, creating images that feel intimate without being salacious.

Dan Rubinstein: In terms of immediacy, or even naivete, do you remember the first time you took a photo as an artist?

Paul Mpagi Sepuya: Not the first photograph, but I could think about the time I had started taking pictures regularly. What you’re talking about is like a kind of surprise, the equivalent of moving a leaf from a rock and seeing that an impression was left where the sun bleached around it.

The early days of Paul Mpagi Sepuya: Photographer

DR: Do you ever think back to your early works?

PMS: When any new kind of work is forming, it’s like trying to make a photograph in a way that I

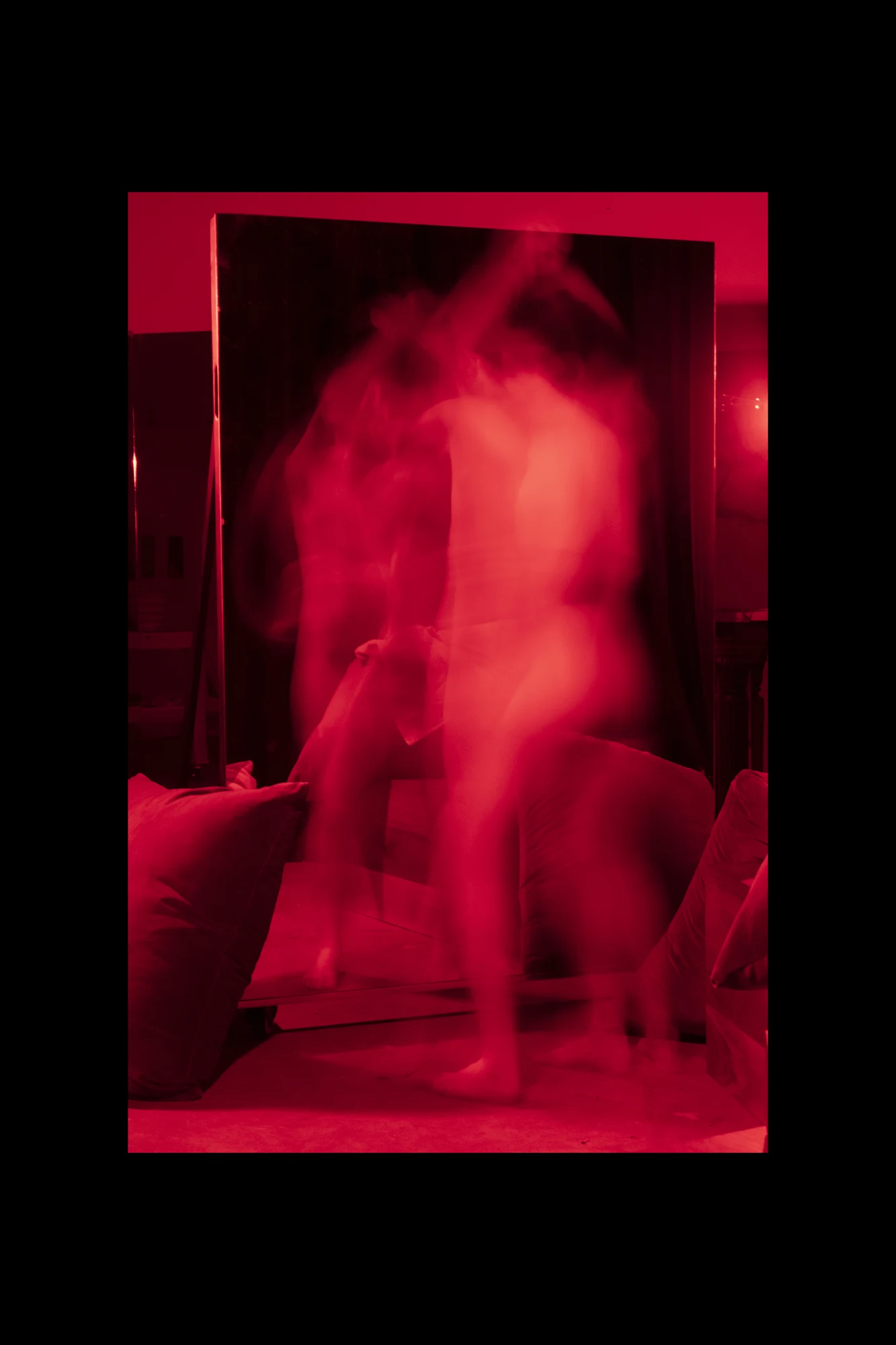

haven’t before. It’s a constant in my life. The dark room series – the ones made under red light.

That experience was unknown to me. I’ve been making work using natural light for the last dozen or so years. It’s a similar shift to when in 2010 all of my photos until that time were images taken in someone’s home, with controlled strobe fill lighting to have a consistency and not create a sense of time of the day. Trying to create new work at night, just on a practical level, was a leap. I used safe lights and then a red one, then LED lights kind of dialed into that same red. There was a lot of trial and error, just taking tests and seeing what it looks like, letting it happen over months, or even a year. After that, experimenting with how to produce them, and then how to print them. Between the last series and this one, there was a break in terms of how the studio is filled out. It’s about pairing a kind of disclosure and explicitness.

Experimenting and forming new projects: Paul Mpagi Sepuya

DR: Do you find that kind of experimentation pleasurable?

PMS: There’s something fun about it, but it’s also nerve-wracking. It’s different as you just go from

being young or just starting out, trying to make those first artistic statements, versus once there’s a body of work that you’re already responding to.

DR: Is the experimentation getting harder over time?

PMS: There’s never a point of just sitting in silence and trying to draft an idea or a thesis of something that’s just been executed. It’s always going to be about responding to what’s around me, what’s in progress. When you look back, only then do you realize that a new project has formed. I’m never afraid of not being accepted. Sometimes, I’ll spend time looking at everything I’m making, look at all the stuff that never makes it past a first review. I get so into things that I think by the time the work is being shown that, oh my God, this is so boring. People have seen this for two years now. I have to remember it’s just me that’s seen it for two years.

DR: You need time to fully digest your work.

PMS: Yes, I need distance from the work. If raw is just like throwing things out there that aren’t fully cooked, I’m the opposite. People should only see the evidence that there was a banquet, from the friends that were there, the recipes used, the tablescape, the eating, the conversation, the wine we drank, how we slept really well that night, and then thinking about how the banquet was the next day. And only then do you tell people about it later. It’s the opposite of raw. For me, that’s what an exhibition is.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya on zines and making connections

DR: In your book, published by Aperture, it mentions your early Zines.

PMS: Zines are something raw and fast. The way in which the early portraits and images I made were just put out in the world in a rapid way. I had all this material and had to do something with it. I was about 23 or something. I would print it and bike around, drop it off to bookstores, and put some in the mail. That’s how I made the first connections and relationships with an audience or art world people and queer zine fans. If I were that age now, would I be making one? Would I just have an Instagram account? I used to have a site where I posted everything, sell prints, and I had a blog where I posted about what I was reading or thinking, or posting contact sheets. It was the opposite of how I work today where things have a one- or two-year time delay.

Rawness – Dan Rubinstein and Paul Mpagi Sepuya discuss the process

DR: Does your work and process feel raw to you?

PMS: It requires being – if I’m going to interpret the terms – not overly planned. There may be certain parameters. When I’m in the studio, there’s only a certain part of what’s possible within the frame. A camera’s going to be on a tripod, which means it’s going to be at a certain height. There’s a certain amount of space. I’m not sitting around sketching out a scene and then trying to construct a tableau. So, in the making, everything has to be within parameters that are open for spontaneity.

DR: Your work is done without Photoshop manipulation.

PMS: That’s something that I had to emphasize, with my studies from 2014 to 2017. The ongoing mirror studies were the ones that people call collage photos. People look at things and just assume it was created using the easier way to go about it, with Photoshop. People have to understand how they’re made and not composites. That’s where the names of the pieces come from, where I used file names and parentheses. Even before the file names, when they were shot on film, I used letters and numbers associated with the roll of film and frame numbers. Now it’s all from a digital camera.

David LaChapelle, Lucas Blalock and Roe Ethridge

DR: When you’re out there, could someone like you be into a photographer that produces

manipulated imagery, like David LaChapelle?

PMS: When I was a teenager I was obsessed with David LaChapelle. In the nineties, if you were alive and looking at pop culture you had to love LaChapelle. When it comes to thinking about teaching, it’s different. I’m going to ask them why they’re creating the art they’re creating and making sure there’s a conceptual thrust to it. There’s a sense of lazy picture-taking where every picture is just an asset to be turned into something else. I tell my students to stop and think about what it means to consider making a picture. Students can often compensate for not having good technical or manual proficiency, lacking an understanding of how to translate an idea into a picture. I don’t allow students in my beginning photo classes to use any manipulation until we have reached the end of the quarter. That’s when we look at artists like Lucas Blalock or Roe Ethridge, people who use these tools of manipulation not to create illusion.

DR: When you’re finding people to be a part of this work, are they friends or models?

PMS: There are friends who are familiar with the work and the space. The making of the pictures in the studio is just working with the ongoing aspects of a friendship or knowing someone. For the newest work, it’s a lot of friends who wouldn’t already know or have seen pictures from my other projects. There’s always a sense of a mirror image, a portrait I could make. I could take pictures and then cut and arrange them and make another thing.

Racialization, sexualization, and gender in photographs for Paul Mpagi Sepuya

DR: What period of time was that series taken from?

PMS: It was the summer of 2021. It started with me wanting to shoot things at night, when friends just want to come by. It was about exploring how to take photographs at night in the space, without using strobes or anything to reproduce daylight in a studio. It was also about asking: What are the conditions of lighting at night in social spaces, like when you’re at a bar or when you’re on the dance floor? But also, what are the conditions of seeing in that darkened space? The larger conversation is about being a part of a community, and within that community understanding how you approach someone. You’re not going to go up and dance with someone. It would be ridiculous to walk into a club having to discuss what’s going to happen. Everything else plays on the nature of friendship, flirtation, and play that’s already present in that relationship. Thinking about nineteenth century photography to early twentieth century photography, getting a more physical sense for how the construction of these early studios and the objects within them, and the ways in which representation and reflection and contrast are used to create concepts of racialization, sexualization, and gender in photographs. I’ve been thinking about the objects and history of it all and to have fun with it. I moved studios in May of 2022.

A black photographer in the 21’s century: Paul Mpagi Sepuya

DR: When you think of those early photographers, do you envy the simplicity of their work,

or wish you would be able to be an artist at that time?

PMS: There’s not one moment of nostalgia. The only person who could really think nostalgically about that time would have to be a comfortably wealthy property-owning white man. Yes, there’s the idea of traveling through time for a sense of romance, but it’s not a liberating idea for most people around the world, unless you’re considering some mythical past that didn’t exist, but not in the context of Western European and North American photography studios, particularly where the aspects of looking and permissions are so prescribed. It was rare to have someone like Augustus Washington, who was a free Black man with his own daguerreotype studio. It was a rare thing for him to be able to construct a position where he’s allowed to look at things with an eye of examination, at a white subject, where at any moment his entire physical being could be subjected to being kidnaped and taken into slavery at any moment. He even had to include in his advertisement that there’s a white woman attendant so that he’s never in the presence of a white woman alone. Even a century later, you had people like Emmett Till being killed due to a false accusation of just looking at a white woman in the wrong way. Photography is tied up in the politics of permission of who is allowed to look at and examine other people, which is why authorship is more relevant than what’s represented in the pictures when thinking about history. If we’re talking about looking at diversity – whatever that empty word means – it’s not about simply pictures of women and queer people and immigrants, for example, but looking at them in queer and non-white ways. There was an article written about my work that used the phrase I pay homage to the nineteenth century photo studio; I’m not doing that in any way.

DR: What does a contemporary artist such as yourself get out of these kinds of historical references? As time goes on, do you find it harder to top yourself in terms of intimacy?

PMS: It’s a way to keep all those things from settling in, and being taken for granted, so it makes them feel a little raw, questionable, troubled or inserting questions into the histories that historians or artists wouldn’t have thought about. Ways in which non-white artists can look at those images, and find a way of relating to them, and opening them up for examination. In terms of intimacy, I keep making work and things change incrementally, and then you realize there’s another project happening. You start to realize where the questions are.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya

Paul Mpagi Sepuya is an American photographer and artist. His images are focused on the artist and subject interaction. He investigates the naked in connection to the intimacy of studio photography. The foundation of Sepuya’s work is portraiture. He includes friends and muses in his work, which employs photography to develop meaningful interactions.

Dan Rubinstein

Dan Rubinstein is a freelance journalist and writer. He also has a podcast named ‘The Grand Tourist’ where investigates design, art, architecture, food, fashion, and travel — all the elements of a well-lived life.