Art curator Ben Broome, interviewed by Lampoon, discusses his pathway to exhibition making, his passion for performances and unanswered questions

Ben Broome is a London-based curator whose work supports promising young artists and challenges the stereotype of exhibition making. Aiming his shows at wide audiences, programming live performances in his exhibition spaces, Broome is a self-taught curator who almost fell in it by chance, but there is no doubt was made for it. For the past six years, he led a group-show series in London, Paris, or New York called Drawing a Blank and organized a month-long exhibition at the Gladstone Gallery in Harlem.

An introduction to curation through friendship

Growing up in northeast England, Ben Broome moved to the capital aged nineteen years old, eager to find a crowd of people that would be his own. He soon befriended creative youngsters, photographers, musicians or artists picking up whatever was around them and making art out of it. «The best thing about cosmopolitan major cities like London, Paris or Berlin is that creative minds gather there. For people who feel disenfranchised, it’s a way to find those people», explained the curator.

But Broome did not really have a practice. He loved punk and rave music, American artist Raymond Pettibon’s album covers, graffiti and skateboarding. He always collected postcards, stickers and a lot of other ephemera, collaging them onto his bedroom’s walls. «I’ve always been a bit of a magpie… I suppose my brain works through physical things», said Broome. At that time, he also worked for a London gallery and thus knew how to hang paintings. The desire to do something with his newly found crowd and being constantly surrounded by artistic people, soon pushed him to organize an exhibition collecting his friend’s work.

In Peckham, not far from the curator’s current place, he found an uninhabitable old house he rented for two hundred pounds a week. He then found some speakers, hung his friend’s art, and programmed various performances. The show was full and happened to be a big success. «For a twenty-year-old, creating something people wanted to see and had a good time at, really sparked something and became a big motivational force», recalls Broome.

Drawing a Blank: A six-show series rooted in youth

Today, Broome keeps on working with people he can call his friends —people that understand him and that he understands—. His approach on curation could be described as very human, putting almost the personalities first and the art second.

He said, «I try not to work with anyone that I wouldn’t go on holiday with. This is a very loose motto. Because if you can spend an intense period of time with someone in a place that isn’t home to either of you, it means that you could probably do the same thing in an exhibition context». For six years, Ben Broome worked on an exhibition series called Drawing a Blank — a pun he came up with when twenty years old—.

«It’s this idea of having no clue what you’re doing, but still doing it», explains the curator. Sort of DIY, those exhibitions were made possible because of Broome’s great network of creative friends. Together they created a community of artists, performers and musicians and within their means, did whatever they could to make those Drawing a Blank group shows happen.

«We had kind of ‘beg, borrow and steal’ a space, a sound system and lights. Everyone chipped in, bringing their artwork in suitcases, hanging it themselves»,explained Broome. Drawing a Blank was a project very much rooted in youth, but the series traveled from closed down bookshops in London to a car garage in Paris or a shut down police station in New York. It got Broome some acknowledgement and taught him to be resourceful.

Ben Broome. Audiences – The formation of taste and opinions

For curator Ben Broome, art should exist alongside conflict. «The best artworks will have unanswered questions…or are in pursuit of an answer. If you find it immediately, it’s not challenging enough. There should be this notion of uncertainty, a feeling that things aren’t easy in order to make good art», he said. However, in his vision any emotions or feelings in relation to artwork — not only fine art, but any artistic practice— is of value.

«Even though an artwork feels bad, it only serves to exemplify and spotlight the things that are good. Bad things provoke conversation. I want to talk to someone who thinks an artwork I find really good is really bad. And vice versa», said the curator, who is very curious about the formation of opinions. Broome believes in the democratization of taste and ideas, for him, no one’s point of view is any more or less valuable than another.

Ben Broome: Why am I doing this?

«I think the opinion of the person who mops the floors at the museum is just as valuable as the director of that museum. It’s just a different perspective. And because of who they are, they could never have the same one», he said, explaining that «we can learn something from everyone in relation to art but also just about life in general».

In this sense, Broome is not very concerned about people liking or not his curation and even find just as valuable not to like it. Nevertheless, viewership is central, and while at work, the curator keeps on asking himself «what am I trying to say here» or «why does that matter?».

He explains: «As any creative person, whether you’re a curator, an artist, a musician or a writer, it’s key to ask yourself, ‘Why am I doing this?’ ‘Why should people care?’ And often the answer is, they shouldn’t care. But having that constantly in mind allows you to check and challenge yourself».

Lack of understanding or lack of explanation

In his vision of curating, a lack of understanding doesn’t mean art isn’t speaking for itself nor is bad. For him, there are places for conceptual work, others for work rooted in academia whether it needs to be explained in simple terms or not. «I think all of those things have merit and it just relates to access points», explains Broome.

For him exhibitions aimed at art educated audiences are as interesting as those for people that are not. But he added, «I do think there is value in a lack of explanation. I like seeing something and not knowing what I’m seeing, not knowing the artist or their ideas behind it. And just absorbing the art piece». In his show Broome does not display many texts on the walls, there might be one at the entrance, and, of course, a press release but there’s one thing the British curator dislikes, is telling the viewers what or how to think.

Ben Broome – exhibition outside institutional settings

«The difference between the exhibitions most people have been to, and mine, is that exhibitions outside institutional settings, [in private galleries], leave more space for people to figure it out for themselves», he said.

If Broome was working for a museum, providing an educational and conceptual framework for the audience would be a requirement, saying that «it’s key that resources are there for people to learn more if they want». Understanding what the curator and artist are thinking also gives the viewer additional context to make up their own mind.

But Broome begins curating for his peers for whom references seemed useless. «Now I think more about the viewer, because I believe in the artists I work with. They’re making interesting work that has power to inspire beyond my immediate social circle. So moving forward it’s relevant to think about strangers in that context», admits the curator.

Entry Points: performances and wider audiences

«At museums, looking at artworks deemed by the establishment to be masterpieces —and many of them are—, I sometimes ended up bored (as a lot of people). Because when presented along with thousands of them, they lose any sense of individual identity», explains Broome before adding, «but there is such a power in boredom».

For him boredom is interesting and does not mean the artwork or the curation is not good, nor does it mean that the institution is failing. But when an artwork snaps you out of that boredom, it’s usually because of how good an artwork is and, in that sense, Broome encourages us —the viewer— to celebrate that boredom and sit in it for a little while. He then added, «When I’m bored, and my mind is lucid, I’m free thinking and often really good ideas come out of that state».

Ben Broome: I’m interested in the power of performance to disrupt gallery spaces

One way, curator Ben Broome found to engage his audience is programming performance on the duration of his exhibitions. «It’s an incredible tool to engage with new audiences. On a totally simplistic level, it gives people a reason to come back and see an exhibition, or maybe just come for the first time», he said. In that way, Broome programmes from musicians to artists talk or performance arts passing by film screenings and poetry reading.

«I’m interested in the power of performance to disrupt gallery spaces and create or redefine the feeling of an exhibition», said the curator. For instance, inviting techno musicians to perform in a white wall gallery space is thrilling in the sense that it’s a forum for disruption, it challenges people, making them uncomfortable or leaving questions unanswered.

«To think about performances alongside art pieces, allow people to continually view the spaces that I curate in different contexts. And maybe it also allows viewers to recontextualize the work. They might think differently about a piece if they’ve seen a performance happen in front of it, or maybe not.» (Laughs.)

Gladstone Gallery

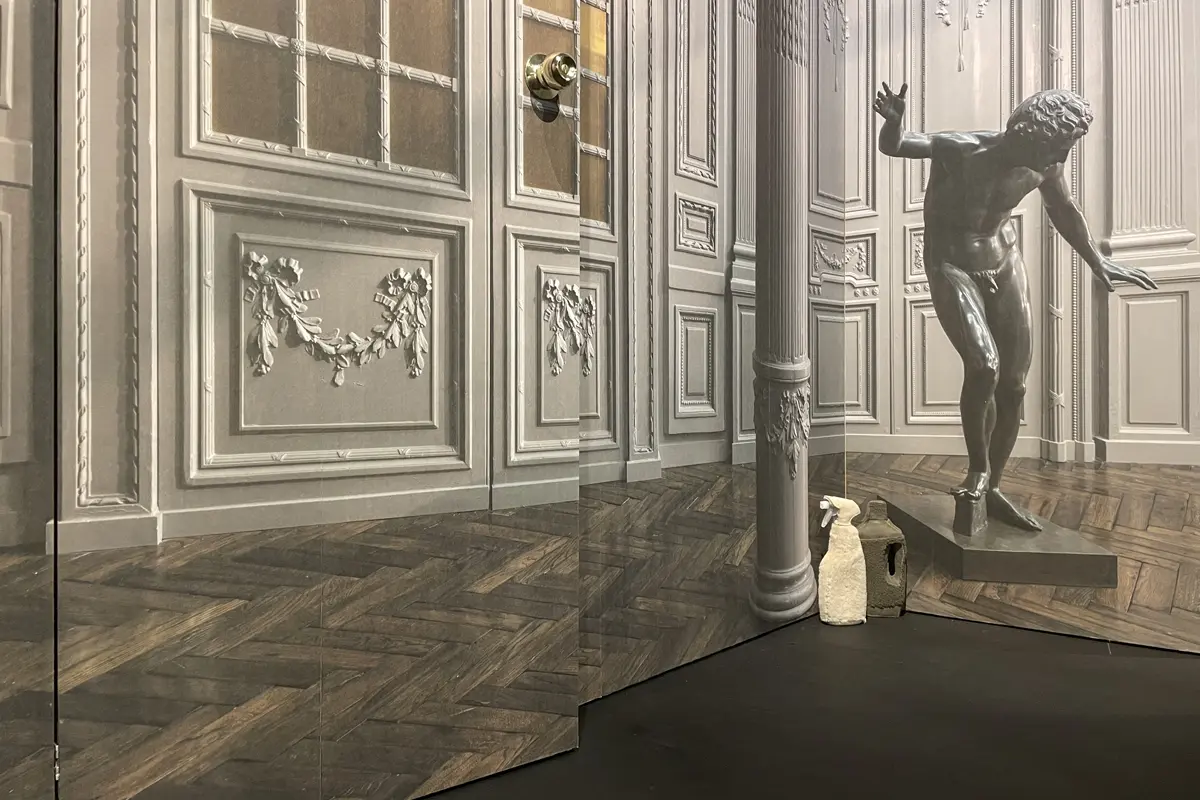

In September, in New York at the Gladstone Gallery, a four-floor building located in Harlem, Broome organized Real Corporeal, a group show reuniting, among others French painter Pol Taburet, performer Sara Sadik or London multidisciplinary artist Rhea Dillon with an accompanying performative program, including French pianist Chassol, Italian DJ Gabber Eleganza, or American performer Joan Jonas.

«I got some really amazing feedback from a whole spectrum of society, which is, what art is supposed to do: engage different people from a seventeen-year-olds, who walked in off the street to an eighty-year-old museum director», said Broome. «People must relate to or have a point of reference from which to get something out of, they don’t necessarily need to like it, but just to engage with it», he exclaimed.

Moving forward: solo shows and replacement

For now, Broome remains in his house in Peckham, focusing his time on individual artists’ solo projects. « Whilst the power of a group show is in this notion of bringing people together and creating community, there’s also value in working with one artist and making something exhaustive — the true reflection of a body of work», he explains.

Drawing a Blank series

Thinking back to his Drawing a Blank series showcasing young emerging artists, he thinks about how this project should keep on living and keep on being anchored in youth. He thus wishes to pass it on to a younger someone.

«I’ll show how I used to do it», said the curator but today his ambitions have changed and Broome feels almost too old to keep on doing it. «So if any twenty-one year-old aspiring curators are reading this… Well, get in touch».

Ben Broome

British curator and founder of Drawing a Blank. After a stint working in a central London gallery, Ben Broome was tired of adhering to the constraints that conventional galleries placed on artists, driven to his own exhibition series and realize his vision, he founded Drawing a Blank in 2016.