Rough Culture: Luciano Baldessari was a Rationalist Rebel

Frank Lloyd Wright claimed that Luciano Baldessari was the only Italian architect whose work he knew – matter and spirit, monumental gestures and the fluidity of theatre

Paolo Baldessari recounts Luciano Baldessari

My uncle Luciano was a tough, rough, generous man. Punctual like a clock and strict about education. Every time he visited our home, he instilled a sense of fear in us. He was witty and sharp, with a love for Kraus-like aphorisms. I remember his sayings: “If you want to be an architect, either be rich or marry a rich woman” and “If I were a client, I would ask the architect to show me his unrealized projects.” His greeting was “Cheers.” His favorite aperitif was rhubarb with seltzer, ice, and a lemon peel. We have revived this drink during the presentations of the C.A.S.V.A. Foundation, established by Zita Mosca Baldessari in memory of Luciano’s work, whom she enjoyed calling Archi. He was flâneur, a gentleman with a Central European charm and flair, who never renounced his roots or the poverty of the family he was born into. He preferred austere-cut gray suits, houndstooth or corduroy jackets, and Oxford shirts.

He fought for the Municipality of Rovereto to acquire the Depero fund at a time when the critical fortune of the Futurist artist was at zero. He helped Melotti establish himself and hosted Carlo Belli during his brief stay in Berlin. He involved the sculptor Fausto Melotti and the duo Figini and Pollini in the realization of the Craja Café in Milan, a hub of spirits and a crossroads of talents—architects, poets, artists, and writers. Ambitious and astute, with great intuition, he did not choose Paris but preferred to immerse himself in the innovative and revolutionary crucible of pre-Nazi Berlin. The memory I have of him is testified by the drawings he gave me. One dates back to his New York period between 1939 and 1945 and depicts basketball players. I was fifteen, and he made it more precious with a dedication.

Paolo Baldessari, who runs a multi-award-winning studio in Milan and Rovereto with his sister, remembers his uncle. He is the Vice President of the C.A.S.V.A. Foundation (Center for Advanced Studies on Visual Arts) at Castello Sforzesco in Milan, which houses documentation of Luciano Baldessari’s work from 1915 to 1980.

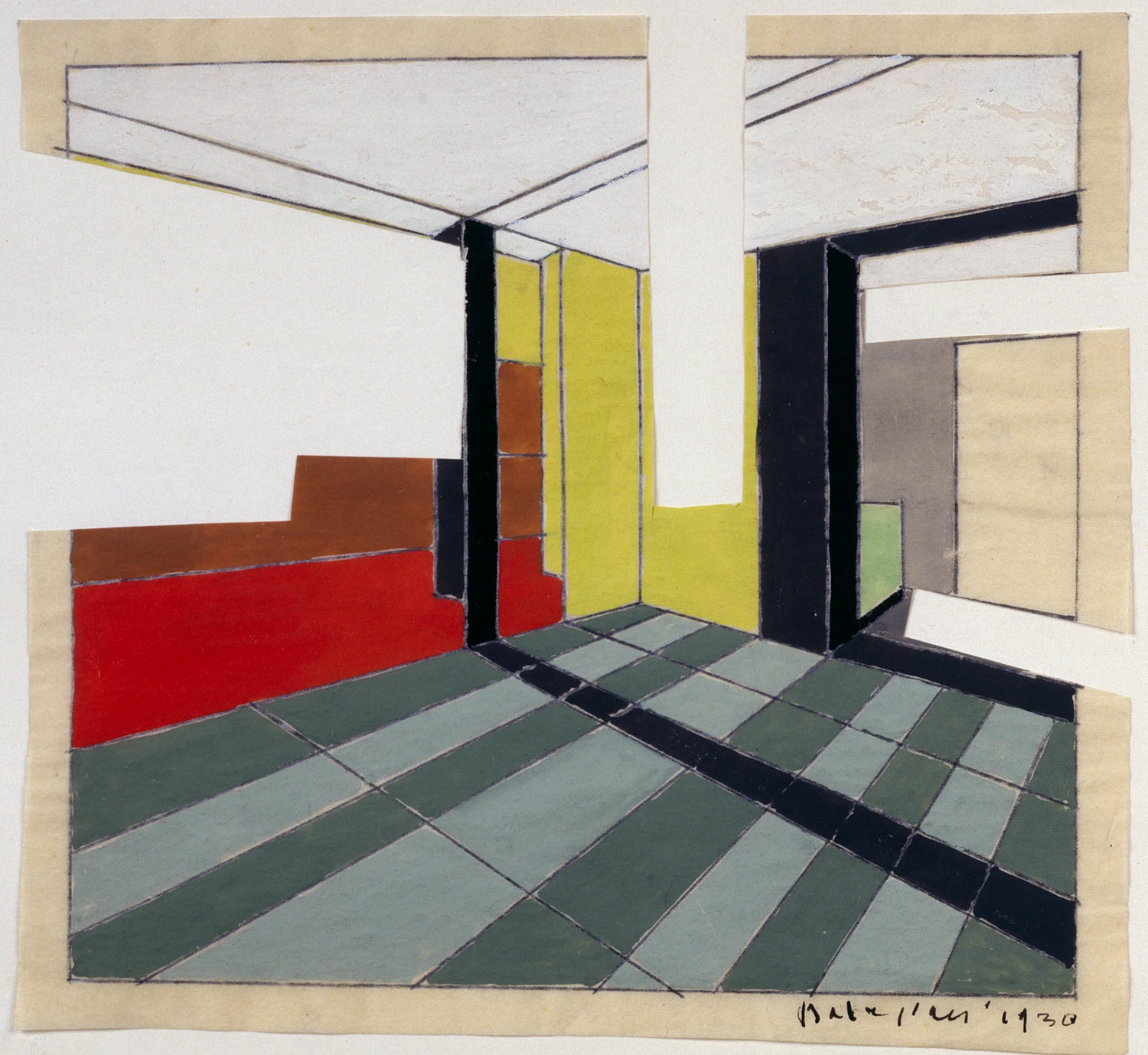

Luciano Baldessari / Drawings

At the Politecnico University of Milan, a further collection preserves 174 projects of urban planning, architecture, installations, and interiors produced by Luciano Baldessari from 1927 to 1982. Another part of his legacy – his personal library, private correspondence, and photographic archive—has arrived at the MART Archivio del ‘900 (Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Trento

and Rovereto). Much credit goes to his second wife, Zita Mosca, a long-term partner in work since 1967, whom he married in 1982 on his deathbed. Zita Mosca had worked as a mannequin in her youth, joined the studio following an advertisement seeking draftsmen. She became Luciano Baldessari’s main collaborator. She was an excellent cook, preparing delicate steamed dishes in their large attic/studio at Palazzo Cicogna, on Corso

di Porta Romana 6, Milano, which boasted

a terrace cut into the roof. It was adorned with some colored iron sculptures designed for the Breda pavilion and now stored in the C.A.S.V.A. archives. Their conversations were enriched by drawings and sketches that explained ongoing projects and accompanied thematic discussions. Besides drawing, he enjoyed composing collages with magazine clippings for color testing and combinations.

Luciano Baldessari / Theatre

He always gave us something, when my sister Michela, who was studying industrial design at the IED, and I left his house, excited and enriched. In January 1982, Luciano and Zita asked us to collaborate on the project to relocate the arches of the 1934 Air Force Hall in Rovereto, reconstructed for the exhibition on the 1930s at Palazzo Reale. Since they would have been destroyed after the exhibition period and given their imposing height of six meters, we had rethought them as urban sculptures with a steel cladding. An idea that remained on paper. Archi has become the name of the series published by the Foundation, the first volume of which Il tempo del Craja was released in Milan last May.

During his career, Luciano Baldessari said: I have designed a lot, realized little and that little not to last but the project is already a sufficient joy. He created many ephemeral installations for exhibitions and trade fairs. He drew with speed and confidence. We are preparing an exhibition that will open on December 16 at the Zandonai Theater in Rovereto (the first public hall in Trentino, erected in wood by Filippo Macari

in 1783). The exhibition celebrates the centenary of the theater’s dedication to Zandonai and its inauguration in 1924, attended by Prince Umberto of Savoy, with Riccardo Zandonai’s opera “Giulietta e Romeo.” It was reborn after the devastation it suffered during World War I when it had been reduced to a stable, a soldiers’ lodging, and a military warehouse.

The focal point of the exhibition will be Riccardo Zandonai, the Rovereto-born composer and conductor, with the prologue, two acts, and an epilogue on a libretto by Arturo Rossato. Luciano Baldessari was called to be responsible for the scenes and costumes for the first performance, which was to be held at the Teatro Sociale in Como in 1927. Everything remained at the level of sketches. After several postponements, the premiere finally took place at the San Carlo Theater in Naples on February 4, 1928, with more traditional staging. Later this year, at our proposal, the sculpture garden of the MART in Rovereto will be named after Luciano Baldessari.

Luciano Baldessari / Villa Letizia

In 1962, he embarked on a creative season that revealed his ability to fuse poetry and functionality, form and spirit. Among the most significant works of that year is Villa Letizia in Caravate near Varese. This is a project conceived for Angiola Maria Campari. In this residence for the blind, Baldessari distanced himself from stricter rationalist dictates. He created a place that is both a refuge and a sculpture, imbued with a sensitivity for architecture as an experiential space. The Chapel of Santa Lucia in the complex is a small Italian Ronchamp where the echo of plastic and vibrant curves resounds in a play of lights and volumes that speaks of transcendence. These projects testify to Baldessari’s desire to explore new languages while remaining faithful to his dynamic vision of architecture, always open to dialogue between man and environment, between the sacred and the everyday.

Luciano Baldessari / Condominio Milano

The Milano Condominium in Rovereto is an architecture that defies conventions and reveals an idea of living where art and form find a high synthesis. Baldessari involves his friend and ally, Lucio Fontana, with whom he shares a vision of rupture and experimentation. Fontana intervenes with one of his ceilings: a surface where the material comes to life and opens into fissures and reliefs in the plaster, taking the spatial dimension to a new level of expressiveness. The result is a blend of languages where the rigorous geometry of rationalist architecture merges with the explosive energy of the Spatial Concept, creating a dialectic between content and container, between rigor and artistic gesture. Breaking away from the rigor of 1920s and 1930s rationalist architecture, Baldessari had already moved the boundaries between sculpture and architecture, abandoning orthogonal axes.

Luciano Baldessari / La Campana dei Caduti

The monument for the Bell of the Fallen (Campana dei Caduti) in Rovereto remains a deep regret for him, after he participated in and won the competition for its realization between 1961 and 1964. Baldessari remained tied to his hometown, although the epicenter of his work was in Milan, where he opened his first studio on Via Santa Marta in 1928. Milan was a continuous experimentation ground, the ideal stage for an architect and set designer with a free and irreverent mind. Milan, with its frenzy, ambitions, and thirst for innovation, thus becomes the faithful mirror of a Baldessari who never stops imagining and interpreting urban space, suspended between tradition and avant-garde.

Luciano Baldessari / La Sala delle Cariatidi

The restoration of the Sala delle Cariatidi

by Piermarini in Palazzo Reale Milan in 1971 marked a moment of reflection and inner return for Luciano Baldessari, almost a temporal bridge to the Berlin of his youth.

That European capital, which in the 1920s and 1930s pulsed with avant-garde and innovative tension, was also revived in the Hansa-Viertel with the skyscraper designed for Interbau, built in Berlin in 1955-57 with architect M.P. Matteotti and engineer Saliva. The neoclassical Hall of Caryatids, a late18th-century spatial ghost populated by fragments of stucco sculptures and decoration, devastated by Allied bombing in 1943, becomes under his hands a stage suspended between ruin and rebirth. Memory dialogues with the present in a play of formal and structural balance. The echo of Max Reinhardt’s stage designs and the functionalist rigor learned in Berlin find new resonance here.

Luciano Baldessari / Luminator

The Luminator lamp in chromed steel, designed by Luciano Baldessari in 1929, stands out as an iconic object of modernist design, a synthesis of avant-garde, functionality, and luminous plastic. Anthropomorphic forms represent the spinning movement of a dancer. This lamp is not just a piece of furniture but a visual manifesto that draws on a crossroads of influences. On one side, it recalls the geometric and theatrical aesthetic of Oskar Schlemmer with his mechanized and stylized bodies of the Bauhaus; on the other, it is rooted in the propulsive dynamic of Futurism with its drive toward technological progress and speed.

Baldessari orchestrates a subtle tension between form and function – a slender, vertical column that channels light, embodying a formal rigor that never relinquishes a subtle spatial poetry. The Luminator celebrates the fusion of art, architecture, and design in a pioneering vision that anticipates the times and remains faithful to the avant-garde spirit of its creator. It was first produced thanks to entrepreneur Antonio Bernocchi. The Luminator Italiana edited it in 1931. Then, the patent passed to Luceplan in 1979. Recently, it has returned to production thanks to Codice Icona, a Verona-based company that identifies and revives emblematic objects by the great masters of the 20th century.

Luciano Baldessari / Caffé Craja

In 1930, in Milan, Luciano Baldessari designed a project of great symbolic significance, the Craja Café-Bar – dismantled in 1964 – on Vicolo Santa Margherita, where he involved the young Luigi Figini and Gino Pollini, recent graduates with Piero Portaluppi, and for the decoration, Marcello Nizzoli – responsible for the metallic mannequin that recalls Oskar Schlemmer – and fellow countryman Fausto Melotti, who was responsible for the fountain made of nickel-plated metals. Melchiorre Bega was entrusted with the wooden furnishings. A stone’s throw from La Scala and the Galleria del Milione, the Craja, like Vienna’s Cabaret Fledermaus, Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire, and Strasbourg’s Aubette, was a laboratory of future ideas, especially under the totalitarian fascist regime.

A rationalist and anti-bourgeois planetary station of thought, an alternative to the overloaded 19th-century décor of Milan’s historic central cafés. Regulars included Marinetti and Persico, conductors like Toscanini and Victor de Sabata, de Chirico and Sarfatti, the Chiaristi painters, and the Campo Grafico Group, who debated animatedly, sometimes leading to violent disputes. They were all desperate for love and passion, rebellious anarchists, as sculptor Luigi Broggini described them. Baldessari would distance himself from this circle as soon as he felt trapped. Once again, he rebelled and refused to be a cog in a homogeneous cultural system.

Luciano Baldessari / Triennale

Luciano Baldessari left an indelible mark on 20th-century Milan with buildings that embodied a dialogue between experimentation and functional rigor. Among his most emblematic works of the 1950s is the complex for Breda, where industrial architecture is reinterpreted in a modernist key with a bold and visionary approach that reflects the essence of a metropolis projected toward the future. Similarly, at the Milan Triennale, Baldessari conceived exhibition spaces that transcended mere function, transforming them into a kind of architectural theater where visitors found themselves immersed in a sensory and conceptual experience in which form became language. On the ceiling of the Triennale’s grand staircase in 1951, Lucio Fontana installed his luminous cloud, now housed in the Museo del Novecento. These buildings are closely linked to an evolving urban fabric, whose cosmopolitan breath recalls the architect’s Central European heritage, distilling in his creations an unprecedented synthesis of rationalism and avant-garde, united by an underlying spatial lyricism.

C.A.S.V.A. Foundation’s President, Anna Chiara Cimoli

C.A.S.V.A. Foundation’s President, Anna Chiara Cimoli, teaches History of Contemporary Art at Università degli studi di Bergamo I was friends with Zita Mosca Baldessari for three decades – she passed away in 2021. Upon her death, she decided to entrust me with the presidency of the C.A.S.V.A. Foundation, which she established at her will, donating both the archival collection she owned, the paintings and studio to the city of Milan. As an equal colleague of Baldessari, Zita was allergic to the concept of being a vestal or guardian of memory. She staunchly defended her competence as an architect and designer, her identity. Zita entered Baldessari’s life in 1967. She knew he was looking for a collaborator, and there she was, climbing to the floor where Baldessari had his studio and home. It was love at first sight. Baldessari never let her go because she was a designer, serious and well-prepared, as well as a woman of charm and intelligence. The story intertwines with something dear to the architect: fashion. Baldessari always loved fashion.

For him, it was another way of expressing himself, a concentric universe in relation to all the various visual languages. Baldessari was interested in fashion like photography, cinema, music. There is that Bauhaus imprint where all this becomes a piece within a vast creative mosaic. The architect immersed himself in Expressionism and the Bauhaus atmosphere during his Berlin years. One flowed into the other. Maybe the shocks of Expressionism had subsided somewhat, fitting into a more New Objectivity dimension. Oskar Schlemmer was a benchmark for Baldessari. Dance, theater, corporeality. Baldessari’s work is full of body

Luciano Baldessari / New York

In 1939, he moved to New York. He was very adept at languages, knowing several. He left for the United States relying solely on his talent. Some connections stemmed from projects imagined for Milan, but never realized, such as the complex in Piazza San Babila. This complex included designs for a cinema, theater, residential area, and shops. Thanks to the American clients of the project, who were also connected to the Rockefeller family, he decided to depart. However, this prestigious entry point did not lead to any tangible results. We are not aware of any successful architectural commissions in the United States. Baldessari’s Politecnico degree was not recognized in the U.S. Fascist Italy posed an obstacle. During those years, Italian architects in the States struggled to sign and build. Baldessari, with the humil-

ity that was his hallmark – despite being a master of drawing and painting – enrolledin courses just like any budding student.

He frequented a series of interesting circles around the MoMA, Philip Johnson, and Calder. At the MART in Rovereto, all the playbills of the ballets, operas, and theater performances Baldessari attended in New York are preserved. One interesting commission he received was from Elizabeth Arden for a fashion theater: the idea was for everything to take place in a true theater. Baldessari envisioned a structure for which we have no blueprints, only visions teeming with people, movement, dynamism, and lights. It almost feels like you can hear the hum of the crowd. This was something he had absorbed directly from his Berlin years. The project was never realized, and no documentation helps us understand it further. As always in Baldessari’s work and in that of great thinkers, nothing is ever lost. Some of these intuitions would surface in his work when he returned to Italy in the late 1940s. We will find them in the setups for the Milan Triennale or in large exhibitions, including those on the Etruscans and the Vincent Van Gogh exhibition.

Luciano Baldessari / Politics

As opposed to other architects who made architecture a banner of militancy, Baldessari never participated in political debates. He kept his distance, a clear-eyed critic, free from any ideological constraints. Yet, he fought fiercely over political issues. He defined himself as an anarchist without having a history of belonging to the anarchist movement. He maintained a combative libertarian attitude, a need for independence beyond constraints, individualistic and politically aware until his last days. Many of his private letters contain sharp observations and harsh critiques. He broke friendship after friendship due to political disagreements. Whenever he sensed a corporate atmosphere, he would flee. He distanced himself from rationalism. He avoided the entire circle around Caffè Craja.

Any group provoked an allergic reaction in him. He paid a high price. Returning to Italy after the war, he was branded as someone who hadn’t been there, as one who had renounced the fight. He avoided competitions because they seemed to carry a corporate air, and he did not want to be flattered in any way. Zita was the same, like him, reserved and almost hermetic. Perhaps they didn’t achieve the fame they deserved for this reason. Baldessari’s work speaks for itself.

His first wife, Shifra Gorstein, whom he married in 1965, was an actress and performer from the Berlin scene of the 1920s and 1930s. We found a photograph online in which she appears in a swimsuit along-side Walter Gropius at Monte Verità. Josef Albers took it. She must have been a special woman, of whom very few traces remain.

At some point, she developed a mental illness. When Zita met Baldessari, he was still married to Shifra, who was already institutionalized in a care home. Zita had very few stories and images of her. I think she met her in person. A ghost from the Bauhaus who brought leaven and then disappeared, a bit like Zelda for Fitzgerald, in a clinic for nervous disorders.

Luciano Baldessari / Zita Mosca Baldessari

Zita was 40 years younger; they lived together without being legally bound. The marriage took place on his deathbed. Total freedom of thought. I didn’t see them together, but I knew Zita well enough to know there was no bourgeois imprint on their relationship. They were open-minded, free people. I believe that their intellectual bond kept them together until the end. Zita was very Milanese, the daughter of Milanese engineers for many generations. She liked to express herself in that dialect which has now been lost. Zita was also colorful in her interactions.

Luciano Baldessari / Scenography

Baldessari was a scenographer perhaps more than anything else. His visions, whether architectural details or building design, were framed. He framed his drawings as if he were looking through a theatrical viewer. A mental device that made him look at things like they were on stage. Anyone who studies his drawings understands this. Baldessari did not follow a style, his own dogma, or a manifesto. Baldessari managed to be abstract in a bourgeois theater world in the 1930s. He worked with Max Reinhardt and then smoothly transitioned to Piscator’s theater, more avant-garde and radical in its representation. He traversed antithetical territories. No one would have asked Baldessari to conform to his language.

Baldessari did not think binary: missed opportunity or not. Time returns. He would revisit his creative steps years later, reinterpreting them, working on them, rethinking them with the mind of that moment.

A unified and ongoing discourse that continues without pause. In Caravate, in the province of Varese in the 1960s, Luciano Baldessari worked on Villa Letizia for the Campari-Migliavacca family, to whom he was connected through his friendship with Depero. He was commissioned to restore this ancient building in a very beautiful landscape area, on the first hills outside the city, to adapt it for residences for the blind. He was ahead of his time in terms of sensitivity: in years when accessibility was not discussed and the tools we have today did not exist, Baldessari envisioned a series of tricks, situations, and methods to assist people. I’ll give just one example: the path leading from the blind residents’ homes to the chapel not only featured handrails and architectural devices, but it was also marked by the scent of different natural essences. There were lavender and thyme areas which guided us through smell. The entire garden was designed to be a place where light and shadow became sensitive, intelligent. The residences were conceived as small housing units that fostered as much autonomy as possible, even though it was a para-hospital structure.

Santa Lucia needs restoration. It is a building filled with spirituality. Baldessari’s ashes were initially brought there before being transferred to Rovereto years later. As the C.A.S.V.A. Foundation, caring for these few still-visible buildings, we would like to carry out a cultural project around the still-consecrated and visitable chapel, a property of the Milan Institute for the Blind. We would like to promote its knowledge to a wider audience, not only as a place of worship but also as a platform for reflecting on accessibility.

The last point I want to emphasize is the ethics of fun. Fun is not an accessory but a component of the project. Designing worlds is a way of living, a way of being in the world. We will eventually publish Baldessari’s letters. They are a sublime experience even from a literary perspective because they mark the story of a person who is having an amount of fun, with confidence and courage, while creating projects of appropriateness. A lesson to remember when complaining: experience everything as a torment, as an immense effort. That ability to express pleasure, even in anger, frustration, and when things go wrong, makes all the difference. As if to say: I’m in it, so I can’t not have fun, I can’t not enjoy this situation to the fullest.

Luciano Baldessari / Biographical notes

Luciano Baldessari was born in Rovereto, near Trento, in 1896 and died in Milan in 1982. His conceptual independence often cost him in a system that demanded allegiance. In 1939, he fled to New York, escaping not just the war but the oppressive totalitarianism imposed by fascism in Italy. Despite difficulties, he connected with Alina Griffith, the sister-in-law of director David Griffith, befriended Alexander Calder, and conceived the Theater of Fashion for Elizabeth Arden, drawing on a similar project he had created in Milan in 1927. In 1945, during a meeting of the College of Architects in NYC, he surprised everyone by advocating for the reinstatement of professionals who had been active during the fascist regime. His humanist vision was too strong to accept judgments and trials. He claimed to be an anarchist.

Baldessari was the sixth child of a shoemaker and orphaned at an early age. In 1909, he began studying drawing at the Reale Elisabettina School in Rovereto, which was influenced by the German Werkbund teaching methods. In 1913, he joined Fortunato Depero’s Futurist Circle. Depero, four years older and a lifelong friend, influenced Baldessari’s creative imprint, which was further enriched by international and experimental contributions. After serving in the Austro-Hungarian army, Baldessari graduated from Vienna in 1918 and obtained a degree in architecture from the Royal Technical Institute (now the Politecnico University of Milan) in 1922. His life reads like a Bildungsroman, set within a dynamic and ever-changing dimension where change was embraced as a necessary means of growth and understanding. Meanwhile, he attended stage design courses at the Brera Academy.

The turning point came in 1923, when Baldessari moved to Weimar, Germany. He settled in Berlin, where he collaborated as a stage designer with theater and film directors such as the Viennese Max Reinhardt (a close associate of Karl Kraus and a co-founder of the Salzburg Festival) and Erwin Piscator (a radical Marxist creator of the Piscator-Bühne, a collective that included Brecht and Döblin). In Berlin, Baldessari came into contact with modernist Walter Gropius, one of the Bauhaus founders, and designed with Piscator a Total Theater where the spectator was involved in a technologically advanced moving machine. He was inspired by Bruno Taut’s transdisciplinary method and met several times with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. He also approached painters Oskar Kokoschka and Otto Dix, a representative of the Neue Sachlichkeit.

In the summer of 1925, he stayed in Paris and exhibited his watercolors in Berlin at the Gurlitt Gallery. Returning to Italy, he aligned himself with the rationalist architects of Gruppo 7 and the Como abstractionists, beginning to form a relationship with the industrialist Carlo de Angeli Frua, who would later become one of his most faithful clients and friends.

In 1927, Luciano Baldessari designed the setup for the Silk Exhibition at Villa Olmo in Como, an event that unfolded between fabrics and a vision of avant-garde exhibition architecture. His work was enriched by international influences and a modernist aesthetic that looked to the future, where space became a living frame of matter and light. Baldessari immersed himself in the interior design of Umberto Notari’s bookstore on Via Montenapoleone in Milan. Here, amid precious marbles and woods, his conceptual hand defined a sober and sophisticated environment. This was perfect for hosting the literary and artistic intelligentsia in a space that reflected 1920s Milan’s cultural fervor.

A restless and creative soul, he never abandoned his passion for stage design. Returning to this expressive language marked a dialogue between space, body, and vision, where his futurist roots and experimental spirit mingled. Baldessari was associated with figures like Giuseppe Visconti di Modrone, with whom he shared a refined and visionary idea of theater. He also embraced Tatiana Pavlova, the Russian actress and director whose avantgarde theatricality he embraced. His collaboration with architect and stage designer, Franco Ferrieri, further fueled this path of contamination, where architecture and stage design merged into an evolving whole.

Cesare Cunaccia