There’s no room for maximalist lines in studioutte’s work

Patrizio Gola and Guglielmo Giagnotti reject sustainability as a trend: it should be inherent to design. Archetypes, simple forms, and a refusal of decor

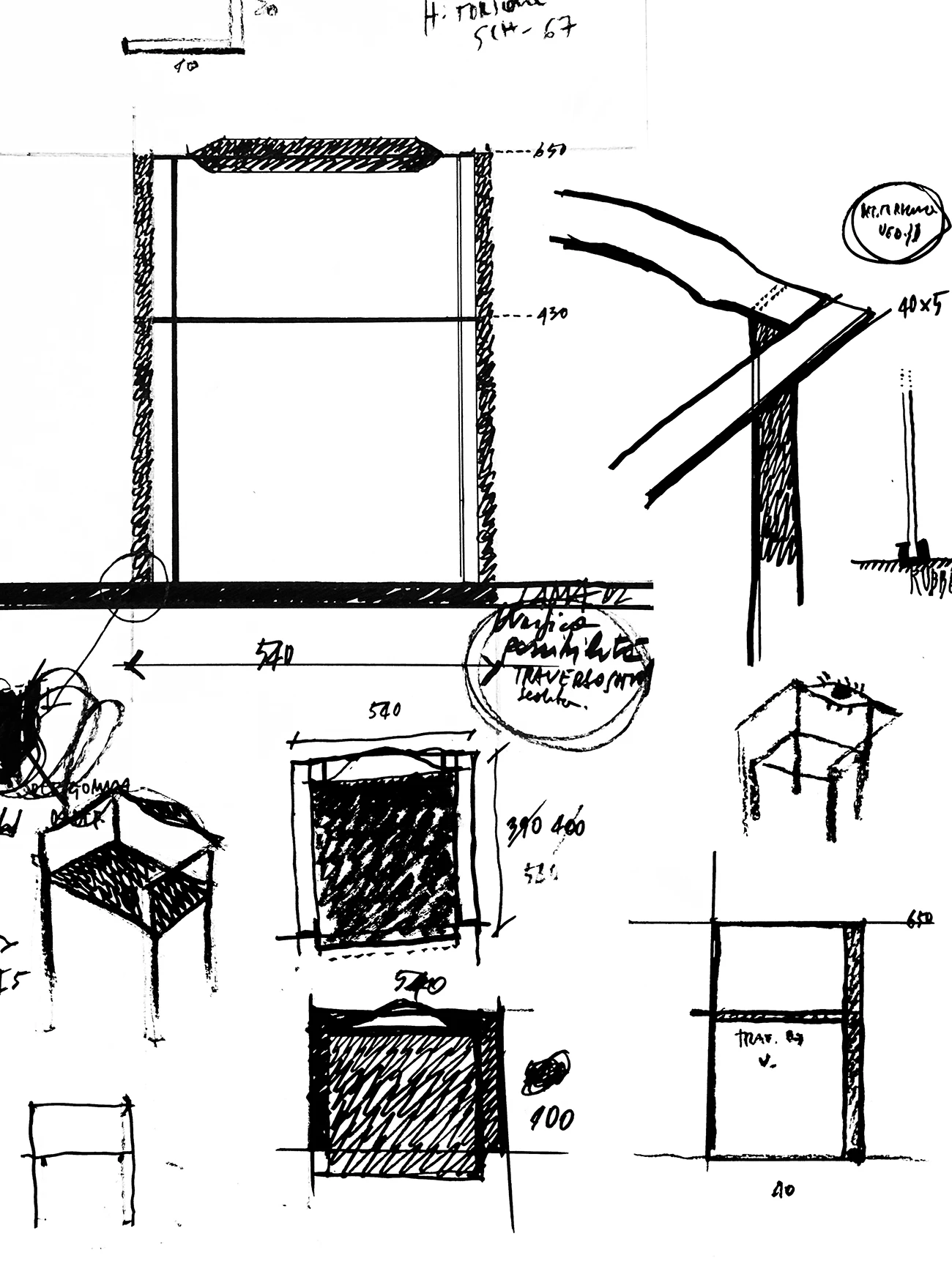

A simple design – in the rudimentary sense. Clean and minimal, yet warm. With a precise idea of sustainability: creating something potentially eternal, or close to it. That’s the core of studioutte, founded in 2020 by Patrizio Gola and Guglielmo Giagnotti in Milan. Their work spans from collectible furniture to interior architecture—chairs, stools, benches, armchairs, lamps, hotels, villas, apartments.

The name “studioutte” (from the German hütte, meaning hut or shelter) evokes their elemental approach. Gola, originally from Sondrio, is an interior designer with experience in hospitality projects between Paris and Dubai. Giagnotti, from Bari, trained as an architect and studied in the Netherlands. When they met at DIMORESTUDIO, Giagnotti had just come from working with Vincent Van Duysen on residential projects.

They describe their work as hybrid—rooted in a study of vernacular architecture, which develops organically in connection with local culture, materials, and practical needs.

studioutte – vernacular architecture and the rudimentary essence of form

The everyday object, whose form “derives from historical adaptability,” is the starting point for studioutte. “It’s a kind of primitivism,” says Giagnotti. “We call it vernacular because it arises from a spontaneous condition—it’s architecture without architects. From that comes a certain austerity, and harshness of form. In the end, all our work in furniture is a pretext to make architecture. What we design as objects is pared down, because it stems from principles and shapes that are inherently architectural. Many brands don’t like the word ‘simple,’ but simplicity—when it’s intentional—is no limitation.”

There’s no room for maximalist lines meant to suggest a contemporary or futuristic taste. No decorative gimmicks. Just a kind of purity—a near-animistic devotion to objects and interiors.

“Everything starts with balancing simple forms, brought to life by specific materials and the combinations between them,” says Gola. “you see what can emerge from extruding simple elements—like a cube—when there’s curatorship, juxtaposition, and a tension between volumes.”

Their vision resists the idea of ergonomics as the ultimate goal: “That’s not our strength,” he adds, “but even absolute forms can be ergonomic. Some objects are necessarily shaped by function. A chair is a chair because it has certain proportions.”

Architectural practices across regions – not geography, but shared language

Another theme central to their manifesto is regionality. Not as a geographic placement. “We mean a shared, almost analog language in architecture,” says Giagnotti. “Our starting point was the regional identity of the Netherlands, especially early 20th-century Dutch neoclassicism. We look to Japan and to forms of vernacular architecture linked to the Alps. Some elements echo African traditions, others the radical Italian design of the 1970s.”

Regionality here refers to a broader human culture—shapes and volumes that become increasingly universal the further back one looks in history. “Some works by Gerrit Rietveld in the Netherlands can be traced back to archetypal Japanese forms. Some aspects of Jean-Michel Frank echo—though more elaborately and differently—certain African elements. It’s all part of a common architectural language,” Giagnotti continues.

studioutte’s idea of sustainability – beyond labels, trends, and historical periods

studioutte’s ultimate goal is to create objects detached from any kind of trend. That’s what sustainability means to them.

“We don’t align our practice with the word ‘sustainability’—in fact, we reject it,” says Gola. “Paradoxically, everything we do is sustainable. To us, it means working with expert Italian artisans to produce high-quality objects that don’t belong to any single era. They can exist dynamically through time. If one of our pieces is made of seven planks of solid wood, you can’t tie it to a specific decade.”

For them, sustainability is about designing products that don’t need to be rethought or revised—things that are, within the limits of the material, as eternal as possible. “Wood, for instance, will never last as long as stone,” Gola adds.

They take a pragmatic approach. Resins or plastics aren’t even part of their design vocabulary. Instead, wood, iron, and stone are. In some cases, a material may not be overtly ecological—because of high extraction costs, for instance— it can still be sustainable if it endures over decades.

We should calculate the fossil footprint of every object

They draw an analogy between the cars we used to drive and those we drive now, including electric ones. The old ones required less maintenance and lasted longer.

Every summer, when Giagnotti returns home, he drives a Vespa from the 1960s. It still starts on the first try.

Gola: “We should calculate the fossil footprint of an object’s production and then weigh it against its full lifecycle. There’s a lot of talk about sustainability, like with recycled products, but then you leave the supermarket with a corn-plastic bag that dissolves in the rain. The environmental impact of each individual piece may be low, but you can’t even use it twice.”

Reuse and repurposing of past installations

This brings up the topic of reuse. “It’s not just an economic matter—it’s a design exercise. It pushes you to rework existing elements,” says Giagnotti.

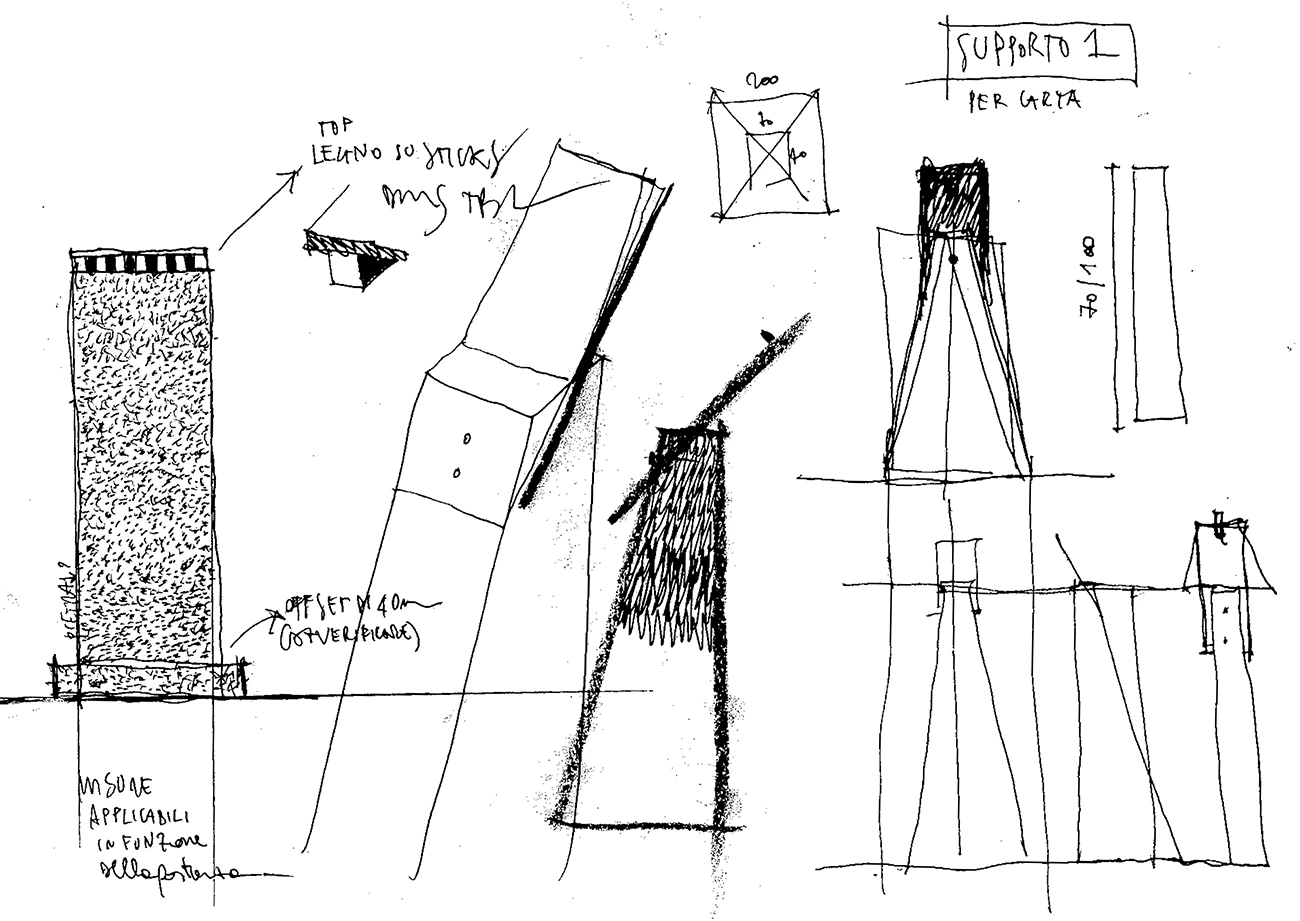

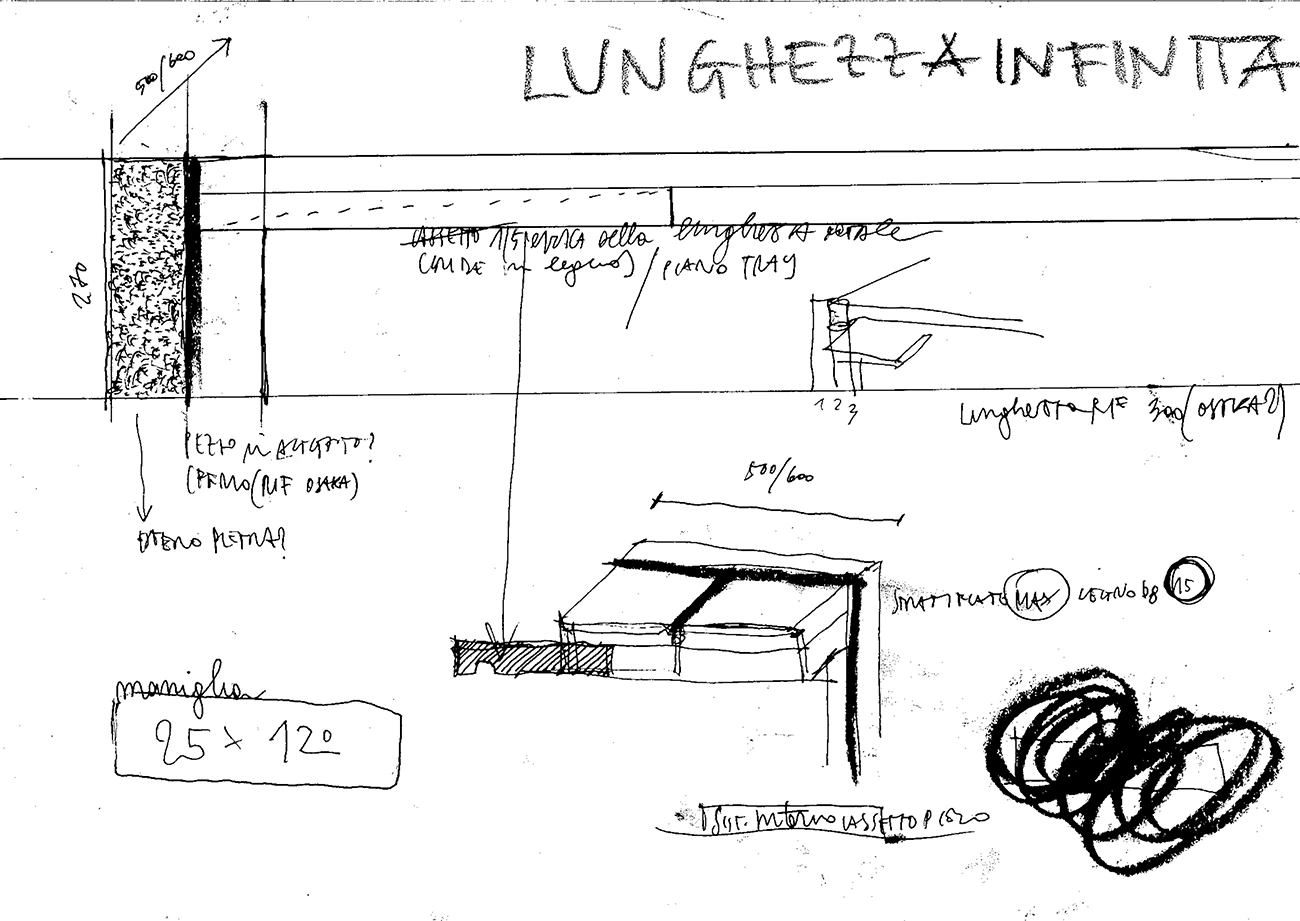

Their 2024 Fuorisalone installation, Waiting Room, was built from drywall studs that were later reused. The aluminum flooring became the desk in their new studio in Milan’s Isola district.

Components from their previous year’s stand for Vietnamese brand District Eight were dismantled and repurposed in the brand’s retail spaces.

For this year’s Fuorisalone, Atollo, they created a monolithic furniture system designed from the start to be long-lasting. It now inhabits their headquarters, with untreated poplar wood paneling concealing doors, windows, and cabinets. A “decidedly humble material,” elevated by a precise geometric scheme.

Milan and design – the risk of losing identity to commercial instinct

Though studioutte’s scope is international, Milan is still home. But with the city in constant flux, is it at risk of losing its identity?

Giagnotti: “In the past, Milan’s design, art, and fashion scenes were grounded in a strong cultural framework. Everything created here had a background—intellectual, literary, theoretical. You could name Munari or Castiglioni, but also the Maniera. That cultural density shaped the product itself—you can see it even in the last gasps of kitsch.”

“Since the 2000s, that approach has faded, replaced by a shallow focus on trends. Now Gio Ponti is back, Sottsass is back, black-and-white minimalism is back. Today everyone’s doing beige homes in the Zara Home style, because the velvet-and-brass phase ended. But these shifts lack a deeper foundation—there’s no theoretical commitment to the objects being designed.”

The Fuorisalone – from design platform to “event factory”

This ties into the debate around Milan’s Fuorisalone—seen by some as the crown jewel of the city’s design scene, but also as an “event factory” driven more by marketing than substance.

“It’s still a key moment,” says Gola. “It gives access to intellectuals, journalists, and high-spending clients who are all in Milan for that one week thanks to the pull of Fuorisalone and Salone del Mobile. But it’s collided with the ‘Milano da bere’ attitude. And now, even among design companies, there’s a tendency to copy one another just to chase trends.”

Gola: “The identity crisis is clearest during events like Fuorisalone. You move from one place to another, but you can’t always remember what you’ve seen. It’s hard to make a lasting impression.”

Giagnotti adds: “Even if you see the most interesting thing in the world, if it’s the last day and you’re overstimulated, you lose focus. It’s like Tefaf Maastricht—a meeting point for the world’s best galleries, from antiques to contemporary. People are there for a purpose. Fuorisalone, by contrast, has become a free-for-all for fashion, automotive, food. Everything becomes commercialized.

Giacomo Cadeddu