Humans can learn from the cooperative system of bees

“Even though the hive is structured as a monarchy, its foundations are provided by a cooperative system”. Photographer Maurizio Annese visits Cascina Linterno, Milan, to explore the dynamics among bees

Maurizio Annese explores the realm of bees to grasp the importance of the sense of community

Even though the hive is ruled as a strict monarchy, its survival depends on the collective work of thousands of individuals. Bees have always fascinated humans because they embody paradoxes: a society that appears hierarchical and rigid, yet is founded entirely on cooperation, interdependence, and constant adaptation. At Cascina Linterno in Milan, this paradox becomes tangible. In the restored rural complex on the edge of Parco delle Cave, centuries of agricultural tradition intersect with contemporary practices of urban ecology, education, and beekeeping. It is here that photographer Maurizio Annese set his lens, not only to document bees at work but to explore what their social structure reveals about our own.

Cascina Linterno: a rural stronghold in Milan’s urban fabric

Cascina Linterno is one of the last surviving examples of the traditional cascina that once surrounded Milan. These rural farmsteads provided food and labor to the city for centuries, connecting urban life to agricultural rhythms. Today, while many cascina have disappeared or been converted into commercial venues, Linterno maintains a cultural mission: to preserve memory while embracing sustainability. Managed by the Associazione Amici Cascina Linterno¹, the site has become a hub for environmental education, urban farming, and biodiversity projects.

The beehives hosted here are more than an agricultural tool. They are symbols of resilience in the face of urban sprawl, pollution, and ecological disruption. By observing bees in this setting, visitors are reminded that even within metropolitan landscapes, fragile ecosystems can survive — provided humans act as custodians rather than exploiters. The Cascina organizes workshops and guided tours where children and adults learn about pollination, the seasonal cycles of bees, and their critical role in food production².

Bees: a strict monarchy that relies on cooperation

When we describe the hive as a monarchy, we refer to the presence of a queen — the only fertile female, whose primary role is reproduction³. Yet the queen does not govern as a sovereign ruler. She depends entirely on worker bees for survival: they feed her, clean her, and regulate the temperature of the brood chamber⁴.

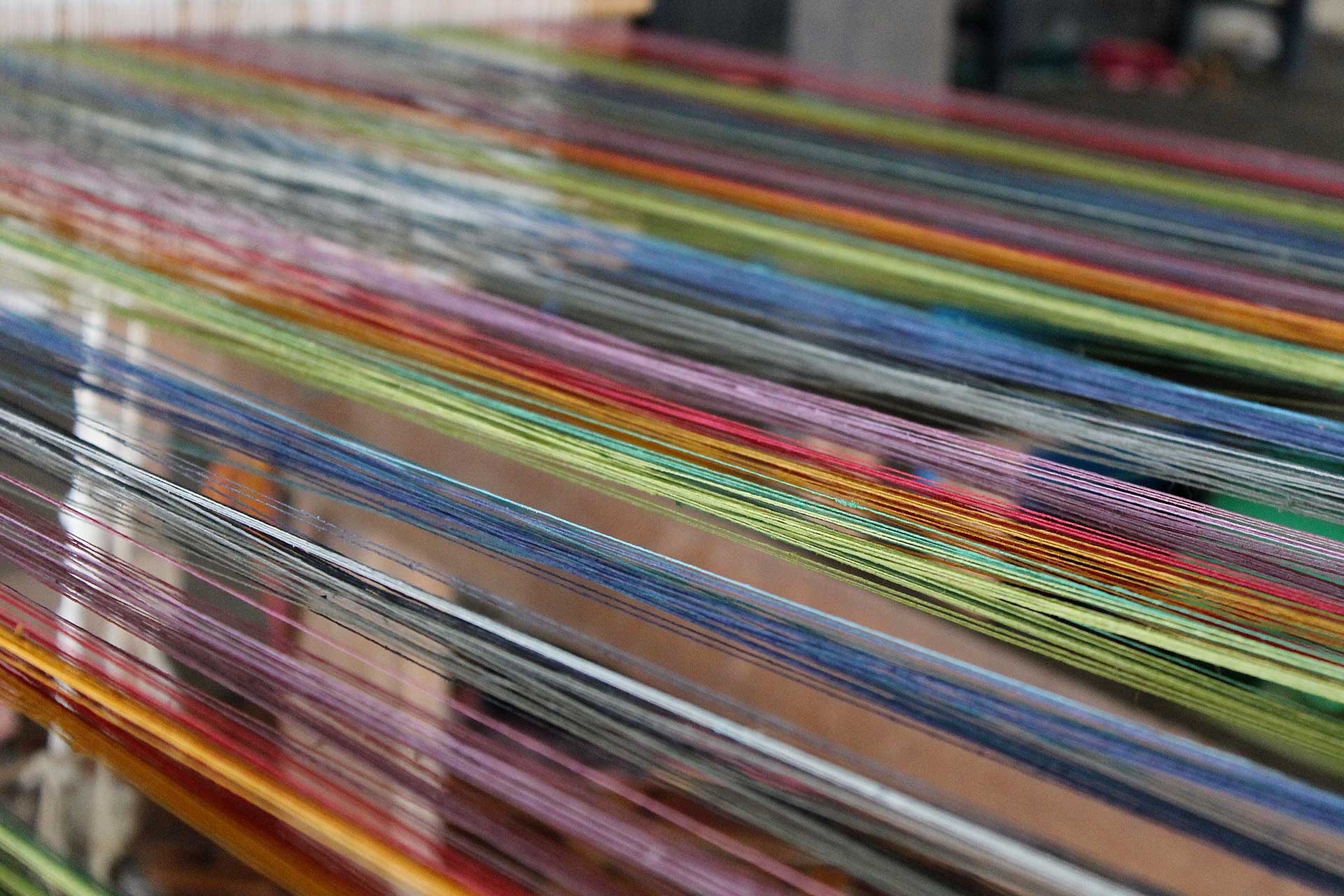

The real functioning of the hive lies in the cooperative efforts of the workers. Thousands of sterile females carry out tasks that shift with age: young bees nurse larvae, later they build combs and store nectar, then they guard the entrance, and finally, they forage outside⁵. This rotation of duties ensures balance and efficiency. Drones, the male bees, exist for reproduction only and are expelled from the hive when winter approaches⁶.

The apparent strictness of the monarchy hides an advanced form of collective intelligence. Decisions such as swarming — when a colony splits and part of it migrates to establish a new hive — emerge from a process of debate and consensus among scout bees. Researchers have shown that these scouts perform dances to communicate potential sites and that the group chooses collectively, with a system resembling democratic voting⁷.

Learning from the cooperative system of bees

Humans often look at bees as metaphors for hard work and productivity. But their cooperative system offers deeper lessons. Unlike human societies driven by individual ambition or profit, bees embody an economy of survival. No bee accumulates wealth, status, or personal power. Each action is calibrated to benefit the hive as a whole. The health of the colony depends on the balance of roles, the distribution of labor, and the capacity to respond to change⁸.

At Cascina Linterno, this lesson resonates strongly. Urban communities often struggle with fragmentation, individualism, and competition for resources. The hive demonstrates that survival is not about domination but about coordination. Cooperation is not a moral choice but a functional necessity. If one group of bees fails in its task — for example, if foragers cannot return due to pesticides or habitat loss — the entire colony collapses⁹.

In ecological terms, the hive mirrors the interdependence of species within an ecosystem. Pollination connects bees to flowers, plants to animals, and ultimately to humans who depend on fruits, vegetables, and seeds¹⁰. The cooperative system of bees is not limited to their hive; it extends to the environment they inhabit. Every act of pollination creates continuity in the food web.

Photography as an act of translation

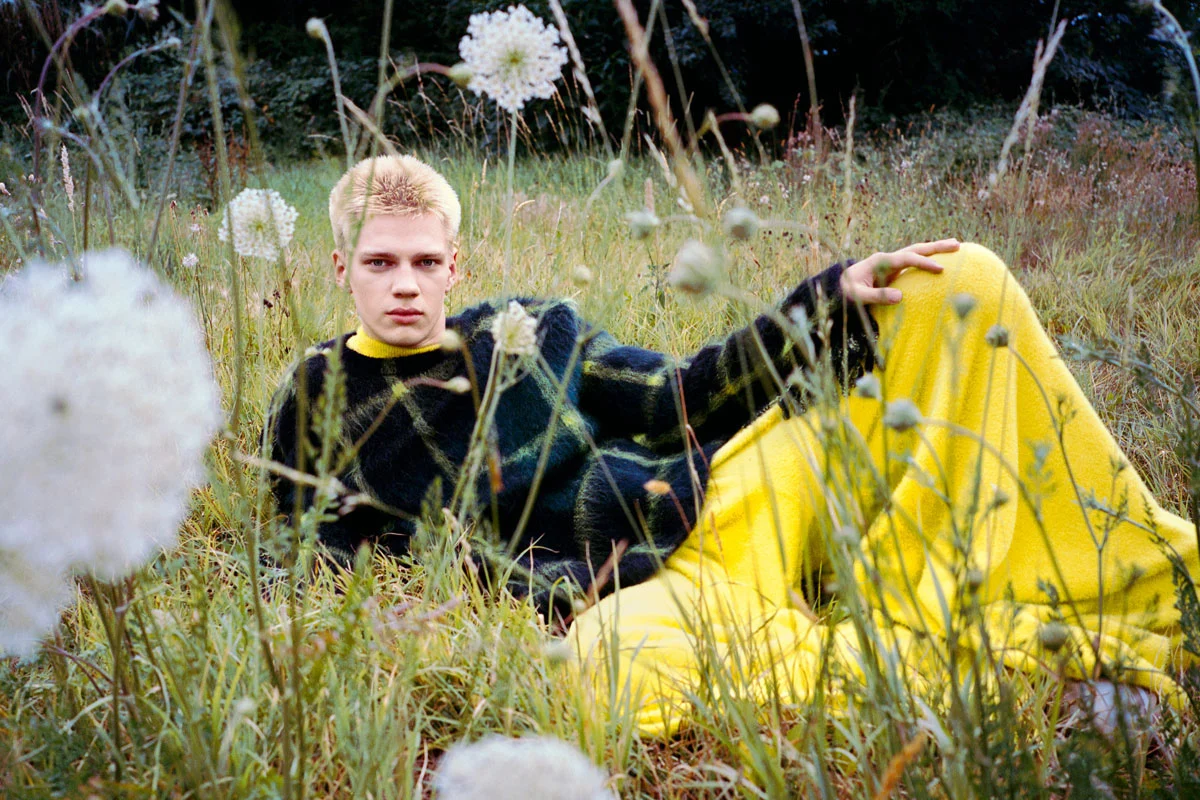

Maurizio Annese approached this subject by seeking to capture the bees’ point of view. Wide lenses distort perspective, allowing the viewer to sense immersion within the swarm, as if the camera were another insect moving through the hive’s world. Bees flew across the frame, sometimes landing on the photographer’s hands or lens, collapsing the distance between observer and observed.

This visual strategy mirrors the cooperative logic of the hive. Just as no bee exists in isolation, no image exists detached from context. The photographs document not only the insects but the broader environment: the cascina’s architecture, the fields beyond, the garments styled by Umberto, which referenced apicultural headgear and protective clothing. The interplay between fashion, environment, and biology highlights the porous boundaries between disciplines.

Urban beekeeping as cultural practice

The reintroduction of bees in urban contexts like Milan is not simply about honey production. It is about reestablishing a dialogue between humans and nature within environments where such connections are often severed. Beekeeping at Cascina Linterno links past and present: medieval farmers once relied on beeswax for candles and honey as one of the few available sweeteners¹¹; today, beekeeping speaks to sustainability, biodiversity, and ecological awareness.

Urban beekeeping also challenges assumptions about where nature belongs. Bees can thrive in cities, often more easily than in pesticide-heavy farmlands, because urban biodiversity provides a variety of flowers across seasons¹². Milan’s parks, gardens, and balconies become unexpected allies in sustaining hives. In this sense, the cooperative system of bees extends to humans who cultivate plants, whether intentionally or not. Every balcony flower box contributes to the survival of pollinators.

What bees reveal about human society

The hive raises uncomfortable questions about human systems of governance and economy. We often equate monarchy with tyranny and inefficiency, yet bees demonstrate that hierarchy can coexist with collective intelligence and cooperation. The queen symbolizes continuity, not absolute power. Authority, in this case, is functional rather than oppressive.

At the same time, bees remind us of the fragility of collective systems. Colony Collapse Disorder, a phenomenon where hives suddenly die, is linked to multiple stressors: pesticides, parasites like the Varroa mite, loss of habitat, and climate change¹³. These crises are human-made, and they reveal how dependent even the most resilient cooperative systems are on environmental conditions.

The cooperative system as a paradigm for sustainability

Cascina Linterno, with its bees and its fields, becomes a metaphorical classroom. Observing the hive allows us to rethink sustainability not as a slogan but as a structural principle. Cooperation among humans, and between humans and non-human species, is not an idealistic vision but a survival strategy. Bees offer a model of resource distribution where nothing is wasted: nectar is transformed into honey, wax into combs, propolis into protection. Waste does not exist, because every substance finds a purpose within the system¹⁴.

This logic could inspire human economies that reduce extraction and waste, moving toward circular systems where resources are shared and repurposed. The hive demonstrates that prosperity is collective or not at all.

Credits

Photography: Maurizio Annese

Styling: Umberto Sannino

Hair: Alessia Bonotto

Makeup: Angela Montorfano

Casting: Irene Manicone

Male model Marvin

Female model Margot

Photo assistant: Andrea Biancofiore

First stylist assistant: Giulia Frogioni

Second stylist assistant: Alessandra Bernasconi

Production: Ksenya Ohorodnik

Beekeeper: Mauro Veca