Celine in Milan takes the city’s most powerful corner, adapting instead of erasing

At Via Montenapoleone’s most strategic crossroads, Celine’s creative director chooses to work with an inherited architectural shell, framing continuity as both a design and sustainability statement

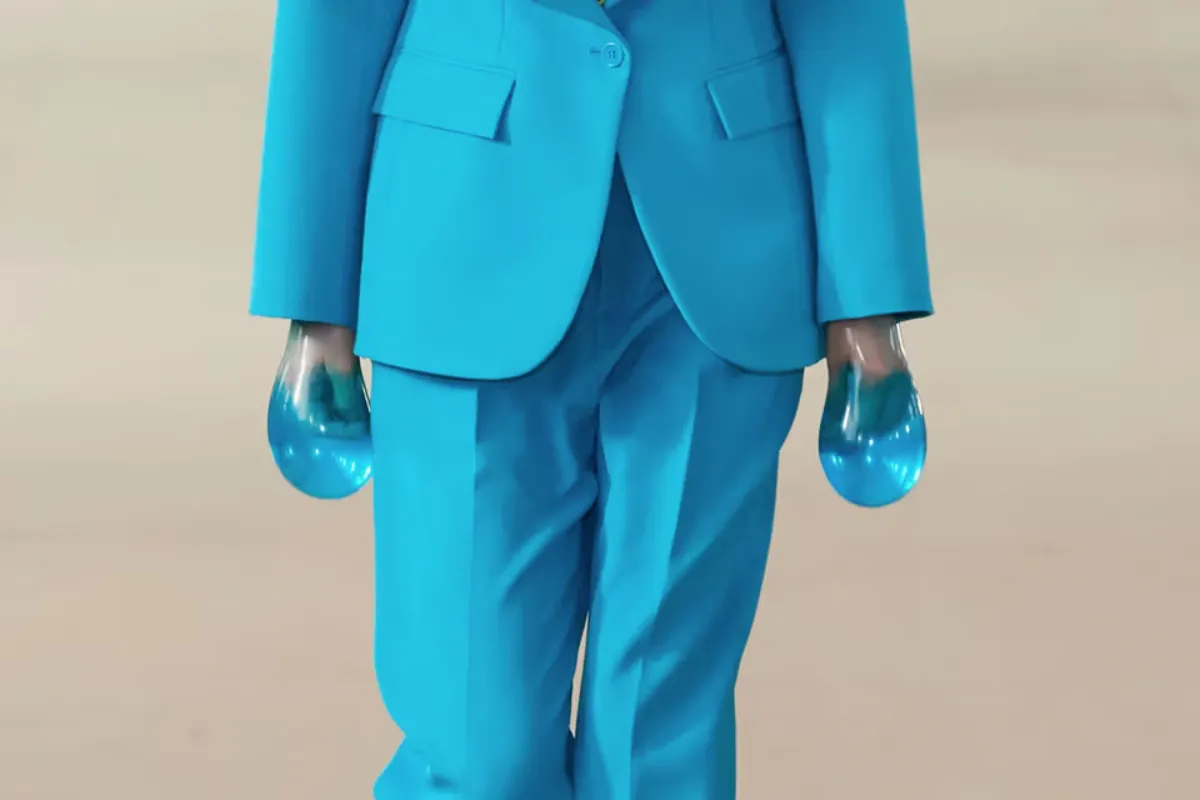

Michael Rider at Celine: a new direction on Milan’s most commercially powerful corner

When Michael Rider took over as creative director of Celine in October 2024, one of his first concrete actions unfolded not on the runway but in Milan, at the intersection of Via Montenapoleone and Via Sant’Andrea. This corner is widely regarded as one of the most commercially powerful points in the city — a place where luxury retail reaches its highest density, visibility and transactional intensity. The opening of Celine’s new flagship here is therefore a strategic move as much as a creative one. This stretch of the Quadrilatero is known for its concentration of global luxury brands, the high footfall and one of the highest average spending levels per transaction in Europe.

Rather than using the occasion to completely erase what existed before, Rider chose a different path. The new Celine store does not announce itself through radical demolition or a spectacular architectural reset. Instead, it is built on adaptation — an approach that treats the existing spatial framework as a resource rather than an obstacle.

Montenapoleone, in numbers: footfall, spending power, real-estate engine

In 2024, the Montenapoleone District recorded 12.6 million unique visitors, up 15% year-on-year and 23% versus 2019. The audience profile is structurally premium (with a high concentration of “high-spender” visitors), and the spending indicators match that intensity: the district’s average tax-free ticket reached €2,525 in 2024 (up 8% vs 2023), a level reported as well over double the national average. Read plainly, this is one of the few places in Europe where high traffic and very high conversion value coexist at scale.

The retail geography is reinforced by real estate numbers that are almost without peers. In the latest global prime-rent benchmarks, Via Montenapoleone sits around €20,000 per sqm per year for top locations — effectively a “scarcity price” that reflects limited supply, long leases, and a constant push toward bigger, more multifunctional flagships. That pricing has gone hand-in-hand with landmark asset moves: in 2024 Kering acquired the trophy building at Via Montenapoleone 8 for about €1.3 billion, and in 2025 the same asset was even reported as the subject of talks around a potential stake sale — a sign that these buildings are treated as financial instruments as much as retail infrastructure.

Openings and upgrades: a district in permanent “flagship escalation” mode

The street’s commercial pressure shows up in the churn of capital projects: the Quadrilatero increasingly rewards brands that build more than stores — destinations that can hold clients longer, add services, and widen the brand’s cultural and hospitality footprint. In this context, “renovation” often means expansion, reprogramming, and experience design rather than a simple refresh.

The “flagship escalation” is visible in concrete, recent moves by the biggest houses. Louis Vuitton, for instance, has turned its Milan presence into a full-scale destination: in 2025 it reopened the historic Palazzo Taverna store on Via Montenapoleone after a major restoration and redesign led by Peter Marino, expanding the concept beyond retail with Da Vittorio Café Louis Vuitton in the courtyard and the DaV by Da Vittorio Louis Vuitton restaurant — a clear signal that the new luxury flagship is expected to host time, services and hospitality, not just product.

A similar logic drives Bvlgari’s repositioning. In 2025 the brand unveiled a new flagship on Via Montenapoleone inside the Taverna Radice Fossati building: a three-floor, 750-square-meter boutique designed to stage jewelry as culture as much as commerce. The opening was paired with “Tubogas & Beyond”, a curated historical selection presented as an exhibition format, and it was also used to announce a patronage project supporting Milan’s Museo del Novecento — again, the flagship acting as a platform for narrative, heritage, and city-facing cultural positioning.

Then there is Fendi, which in late 2025 raised the bar in terms of scale and mixed-use ambition with Palazzo Fendi Milano: a 910-square-meter, four-floor landmark at a key corner of the district, conceived not merely as a boutique but as a “house” with an in-house Atelier and a hospitality layer integrated above, including multiple Langosteria dining concepts. Together, these examples show what “upgrades” now mean in the Quadrilatero: bigger footprints, longer dwell time, more services, and a steady drift from store-as-shop to store-as-urban destination.

Reworking the Celine Montenapoleone flagship through architectural continuity and limited intervention

Celine’s Milan flagship extends over more than 600 square meters on two levels. The project does not overturn this basic arrangement; it refines the way each floor is used and experienced. Existing structural elements are retained, while new surfaces and details define the updated identity of the store.

Rather than inserting a completely new architectural language, Rider and the Celine teams introduce a vocabulary that can sit on top of the previous one. This is visible in the way materials and circulation are handled. Structural walls remain in place; circulation paths are clarified rather than redrawn. The intervention concentrates on surfaces, finishes, lighting and the addition of key elements such as the central staircase.

From a sustainability angle, this choice has immediate consequences. Every wall that is not demolished, every ceiling that is not rebuilt and every façade that is not replaced reduces the volume of waste, the amount of new material and the energy needed for construction. The project frames this restraint as part of Celine’s design culture, not as a separate environmental gesture.

Material language of the Celine Milan store between marble, mirrors and oak staircase

The renewed store uses a controlled palette of stones and metals. Floors on both levels are in Grand Antique marble, a sharply veined black-and-white stone that sets a graphic base for the collections. Walls alternate between Oyster Calacatta and Arabescato marbles, combined with grey travertine. The result is a clear, repeating sequence of light and dark surfaces that can support different merchandising layouts without losing coherence.

Mirrors, framed in antique gold, amplify the depth of the rooms and open diagonal views across the space. Black lacquered walls introduce pauses within this mirrored field, allowing specific product stories to stand out or recede as needed. The architecture is designed to be re-readable: the same planes and reflections can host different seasons and narratives with minimal physical change.

At the center of the project stands a new metallic staircase in polished gold tones. It connects the ground floor to the upper level and acts as a vertical pivot rather than a monument. Oak and glass blades run along its structure and are lit intermittently to underline the height of the space. The staircase does not erase the memory of the previous boutique; it inserts a strong new element into an existing framework, suggesting how Rider intends to work with the brand’s heritage and with the built environment it already occupies.

Store layout in Via Montenapoleone as a flexible platform for womenswear, menswear and accessories

The flagship is organized according to clear, legible functions. The ground floor is dedicated to leather goods, accessories, fine jewelry and Celine Haute Parfumerie & Beauté. Customers enter directly into this universe of bags, small leather items and fragrance, where fixtures are arranged to allow fluid movement rather than rigid zoning.

The upper level hosts womenswear and menswear ready-to-wear, textile accessories and the Celine Maison offer. Here the French-inspired chevron oak flooring sets a different pace from the marble below and recalls domestic interiors more than retail environments. The floor includes open lounge areas and private salons for appointments, fittings and quieter conversations.

This distribution reflects Rider’s decision to treat the boutique as a long-term platform rather than a static set. The layout is intended to support multiple uses: seasonal collections, capsule presentations, appointments with regular clients, as well as potential in-store events. Because the fundamental structure has not been radically altered, these uses can evolve without requiring further invasive construction. This is another way in which the project links sustainability with flexibility: the more scenarios a store can host without rebuilding itself, the longer its architecture can remain in place.

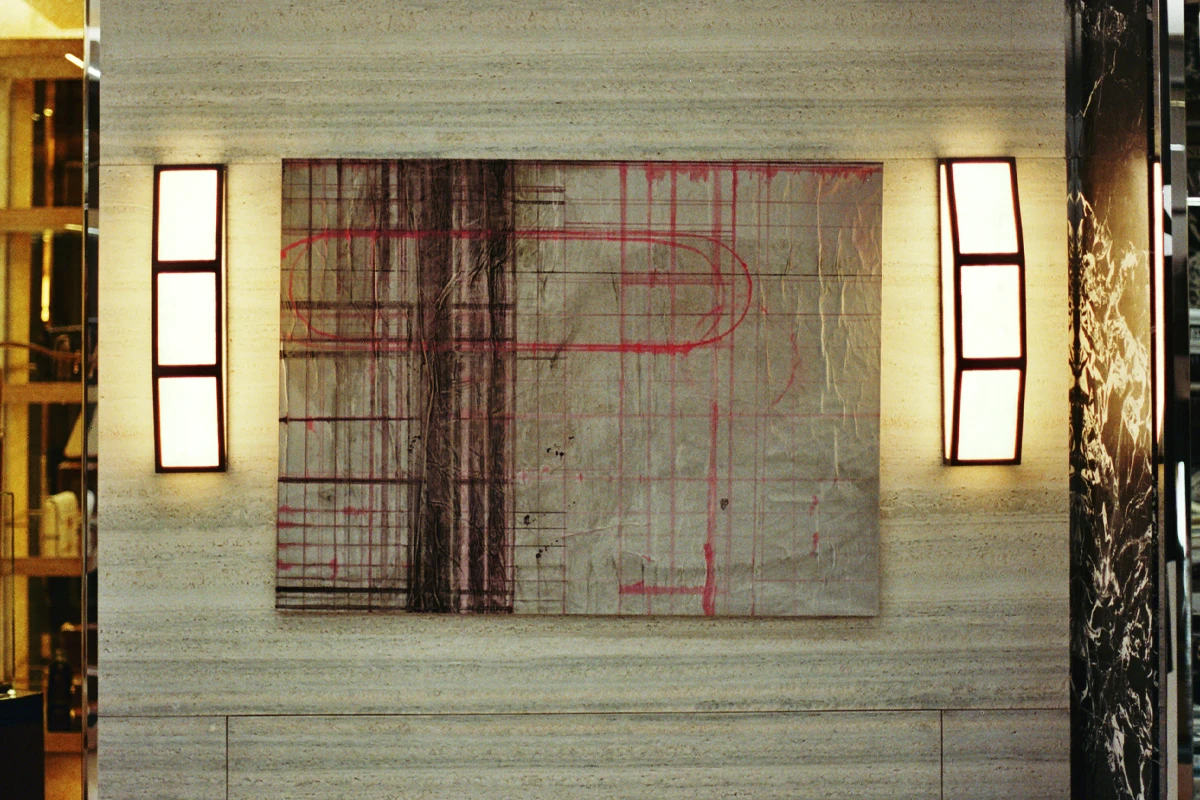

Celine Art Project in Milan: contemporary artworks integrated into retail architecture

The Montenapoleone store also extends the Celine Art Project, the program through which the brand commissions or acquires works from contemporary artists for its spaces. In Milan, this takes the form of a multi-artist presentation across the two floors, in which paintings, sculptures and ceramics share shelves and walls with clothing and accessories.

Visitors encounter glazed ceramic pieces by Peter Schlesinger, a figure whose practice bridges photography, painting and pottery; an early work on paper by Susan Rothenberg; and a relief by Luisa Gardini, where texture and matter blur the line between painting and sculpture. Other works in the store include a portrait by Giangiacomo Rossetti, brass sculpture by Yngve Holen, fiberglass forms by John Duff, stoneware figures by Simone Fattal, a large-scale work on paper by Samuel Hindolo and a wall piece by John Carter.

The presence of this collection is not merely decorative. It changes the rhythm of the boutique and provides a counterpoint to the commercial activity. Artworks offer additional layers of meaning to the materials already present: Holen’s cast agave leaf echoes the metal of the staircase; Fattal’s stoneware interacts with the travertine and marble; Carter’s wall work dialogues with the use of flat color and voids in the architecture. Because these interventions happen at the level of display and curation, they can evolve without requiring structural renovations, again reinforcing the logic of a space that can change while remaining physically stable.

Sustainability in luxury retail: why adaptation of existing stores matters for Celine

The Milan flagship brings into focus a question that is becoming more pressing in luxury retail: how “new” does a store need to be when a brand changes direction or updates its image? Full demolitions and complete redesigns deliver clear before-and-after visuals, but they also come with a high environmental and economic cost. Rider’s decision to work through adaptation, rather than replacement, offers an alternative model.

By keeping the core of the previous Celine boutique intact and concentrating on surfaces, layout and artistic content, the Montenapoleone project demonstrates how a store can signal a shift in creative leadership without generating an unnecessary amount of waste. The architectural narrative aligns with Rider’s broader approach at Celine, which seems to favour continuity and accumulation over rupture: existing codes are not discarded but repositioned; new elements are added in dialogue with the old.

For Milan, a city where historic buildings and contemporary luxury functions often coexist within the same block, this method is relevant. It acknowledges the urban fabric and the investments already made in it, while allowing brands to update their presence. For Celine, it marks the beginning of Rider’s tenure with a tangible, spatial gesture: not an empty box rebuilt from zero, but a carefully reworked space that accepts its own past and treats restraint as a resource.

Matteo Mammoli