Can cinema define itself as a sustainable and inclusive industry?

Inside the film industry’s green awakening: from solar-powered sets and recycled costumes to mentoring programs like Women in Film & TV and the BFI diversity standards

Behind the magic: how temporary film sets reveal the hidden waste and fleeting illusion of movie making

On a bright August day, walking home from grocery shopping, a strange sight caught my eyes – a fleet of wooden huts, rattan reindeer, spools of festoon lights and dozens of security guards dotted around Glengall Bridge in Crossharbour. It was awfully early to open a Christmas market. Only when I saw a shopping cart chock full of candles making its way towards the bridge that I realised – this is a set build.

A week’s construction later winter coated supporting artists, idling action vehicles, neatly netted Christmas trees, endless market knick knacks and a Santa with a giant sleigh took over the fake snowy streets. The commotion lasted for a few days, then in a single day every reindeer got packed up on trucks, all the decoration disappeared and the last bits of fake snow got shovelled into skips.

Overbuying, overbuilding, overshooting: how the film industry’s excess culture fuels waste and unsustainable practices

Filmmaking is a wasteful endeavour. We pull up mile long street facades in studio backlots only to be taken down in a few week’s time, crash luxury cars in the name of entertainment, and rig massive explosions for three seconds of drama. According to a Screenrant article in 2020 the first 7 films of the ‘Fast & Furious’ franchise destroyed and estimated 1,487 cars, while Michael Bay nonchalantly asked if he could blow up Winston Churchill’s house during the filming of ‘Transformers: The Last Knight’. He was denied the privilege.

It may seem eccentric, but if the script calls us to the middle of nowhere with zero infrastructure in place, filmmakers will build a makeshift civilization in order to operate business as usual. We’ll set up our base camp with generators, catering and wastewater facilities, pave the sand dunes with heavy-duty trackway mats for our cranes, and lay the grass with temporary road panels so our 12 tonne costume trucks won’t get stuck in the mud.

Even the films that don’t have the cash to splurge on glitz and glamour will fight for the freedom of choice. We protect ourselves from getting creatively cornered by overbuying, overbuilding, overshooting. We love amassing a surplus to cover our backs. Duplicate props allow for quick resets, breaks and damages, while racks of costume options guarantee that no last-minute supporting artist will ever look out of place. Backups of the backup hard drives superstitiously ward off the threat of lost footage, even if half of it ends up on the cutting room floor anyway.

The single-use monolith: inside the high-speed, high-pressure production system that prioritizes output over sustainability

No matter the budget, ambitions will usually outgrow resources. During the growing pains, when we can’t stretch the bottom line any further, we reflexively fall back on the only remaining efficiency tool – pushing people to work at the speed of a Formula1 pit stop. Under those expectations, sweet little time remains to research the best solutions to keep the machine running.

Such relentless pressure has smoothened decades of bad industry practice into the path of least resistance. When decision makers prioritize product over process, critical thinking goes out the window, and the autopilot takes over. There’s no rhyme or reason behind our panicked actions, it’s just ‘how we do things around here’. It’s easier to tread the same paths than risk venturing into uncharted territories.

The smoke and mirrors of showbiz is there to distract us from the ruthless single-use culture of old school film production. Traditionally, both planet and people were deemed rather disposable, as long as the show kept going on. After wrap, suddenly heaps of ‘assets’ turned into useless waste, whether we’re talking consumables thrown into skips or the human capital left collapsing under the burnout culture.

But even during my mere 13 years in the industry I’ve seen a radical cultural shift. The autopilot irresponsibility of our elders is gradually getting phased out by a new generation of leaders. We realized that ‘the industry’ doesn’t care about its people. We have to care about the industry.

Two revolutions hand-in-hand: the rise of inclusivity and environmental awareness in modern filmmaking

In tandem with transforming the bro down culture into inclusive sets, filmmaking is also going through its environmental awakening. A diversifying workforce is now starting to demand a more conscious workflow. We won’t turn a blind eye on exploitation and abuse anymore, and that waryness extends to the mistreatment of Mother Earth.

Previously, the blatant gender inequality and lack of cultural diversity created a microclimate that valued fast and furious execution over careful and considerate methods. Nowadays sound stages are designed to be energy efficient, while studio films budget for not only Asset Management teams and Sustainability Coordinators, but also Wellbeing Facilitators to save on the bottom line. We finally have entire departments whose sole job is to build a production’s eco-system from prep to wrap with circularity and social sustainability in mind.

When it’s feasible for a production to work with environmentally friendly contractors, providers, builders, caterers, or equipment, it’s really only the inertia of bad practice that could hold them back from doing so. Admittedly, it took us a long-long time to override that inertia. In the UK, organisations such as BAFTA’s Albert, ADGreen and Greenshoot have been campaigning for over a decade to normalise nebulous concepts like carbon literacy or energy offset, slowly seducing the hard-headed executives to treat sustainability standards as a badge of honour.

The cultural awakening: how diversity, mental health, and environmental responsibility are reshaping the film set

At the infancy of this cultural shift, I worked on a few commercial projects as a Sustainability Steward. Back then the aforementioned organisations just started offering Green Certificates, hoping to lure productions over to the path less traveled. But the whole ‘green initiative’ had the reputation of a prestige box ticking exercise that brought more complications than rewards. Flagship advertising agencies flaunted their certificates without any real care or consideration for the environment while smaller productions stood no chance to afford the luxury of going green.

The old school filmmaking machine hasn’t been designed with social sustainability and environmental wellbeing in its DNA. Electric vehicles, solar powered generators, energy saving LED lighting, recycled fabrics, non-toxic paints or biodegradable tableware were either very costly to source or outright non-existent. It went directly against the industry instinct to go paperless, spend time on plannig a waste strategy, build a shared circular resell market or simply ask drivers to stop idling their engines all day.

Without an industry-wide collective reform both in inclusivity and environmentalism, no individual production would’ve been able to topple the single-use monolith of filmmaking. Even in traditionally male-dominant departments such as camera, lighting, grips or construction, we are seeing the rise of female and non-binary crew members and heads of department. These modern creatives carry an inherent responsibility for their own cultural footprint, advocating long-term planning over short-term problem solving.

Building an inclusive future: how diversity programs, creative networks, and mental health initiatives are reshaping the film industry

Programs such as the mentoring scheme run by Women in Film & TV or Reel Impact geared towards Black and Global Majority filmmakers has helped many with training and resources, while the BFI’s Diversity Standards enforce inclusivity requirements in order to access government funding.

According to the Creative Diversity Network’s latest Diamond report, the off-screen representation of women, LGBTQ+ people, BAME groups, and people living with disabilities have all increased between 2022 and 2024. The rise is incremental but steady since 2016, when the Diamond (DIversity Analysis MONitoring Data) system was established.

The Film and TV Charity’s 2024 Looking Glass survey revealed that all the above subgroups are at greater risk of poor mental health and experiencing adverse conditions or behaviours in the industry. The charity constantly tries to keep a finger on the chaotic pulse of the screen industries with surveys, toolkits and a 24/7 support hotline, as we’re gradually inching away from decades of ingrained malpractice towards an actually inclusive future.

Rewiring the industry’s DNA: the new era of green tech, circular set design, and zero-waste film production

The growing demand for resource-efficient workflows is ushering in a new era of eco-friendly providers, fuel-free power sources, reuse networks, broadcaster funding schemes tied to environmental action plans, and industry-wide pledges to work towards net zero production.

BAFTA albert has a comprehensive suppliers directory for kit rental houses with green solutions for generators, batteries, or lights; transport and facilities companies providing fleets of solar or electric vehicles; builders guaranteeing non-toxic and recycled construction materials; costume and prop houses saving unwanted items from going to waste; caterers offering local, seasonal and plant-based options; and waste management companies who are committed to recyclable and biodegradable solutions.

Initiatives such as Set Exchange or Scenery Salvage have been putting great effort into building a circular network for building materials. Studios in and around London are building their own on-site energy solutions, recycling hubs, and water refill stations. Even organising data storage, handling paperwork, conducting meetings or travelling internationally has carbon-friendly options available and unlike a few years ago, the green approach is often the more cost-effective solution.

Does film have a self-sustaining future? why the industry’s next big trick must be building for permanence

Making a film is no different from operating a purpose-built pop-up village. The infrastructure and the inhabitants are in a symbiotic dance, both parties needing to take the right steps in order to move in the right direction together. The bottom-up desire to maintain a lifelong career in a fast-moving industry and the top-down incentive to make a profit in a risky business need to meet in the middle and build mutually beneficial ways that prioritize collective wellbeing over individualistic greed.

We now have the means to manage productions in ways that don’t destroy natural habitats, don’t leave heaps of waste in landfills, don’t poison the air or waters, and don’t exploit crew and cast. Both social and environmental consciousness have a long way to go but they seem to be rising hand-in-hand. As long as the demand is there, supplies and solutions will keep developing as well.

The illusion of permanence: why the future of sustainable filmmaking depends on building systems that outlive the spectacle

So is film a sustainable business? Historically, far from it. But in recent years dedicated professionals kept proving that we can endlessly reinvent ourselves and build work environments that serve and sustain us. Even if the change is incremental, it seems to be irreversible.

The industry of illusion now needs to master a new trick — permanence. Even if our worlds appear and vanish overnight, our systems must carry a thoughtfulness that outlives any single production. Our care has to extend to the industry as a whole. If we want to keep snowing down streets in the middle of summer and conjuring grand spectacles for fleeting moments of wonder, then it’s our collective duty to design ways of working that endure — not for a week, but for generations.

Text: Alex Mill

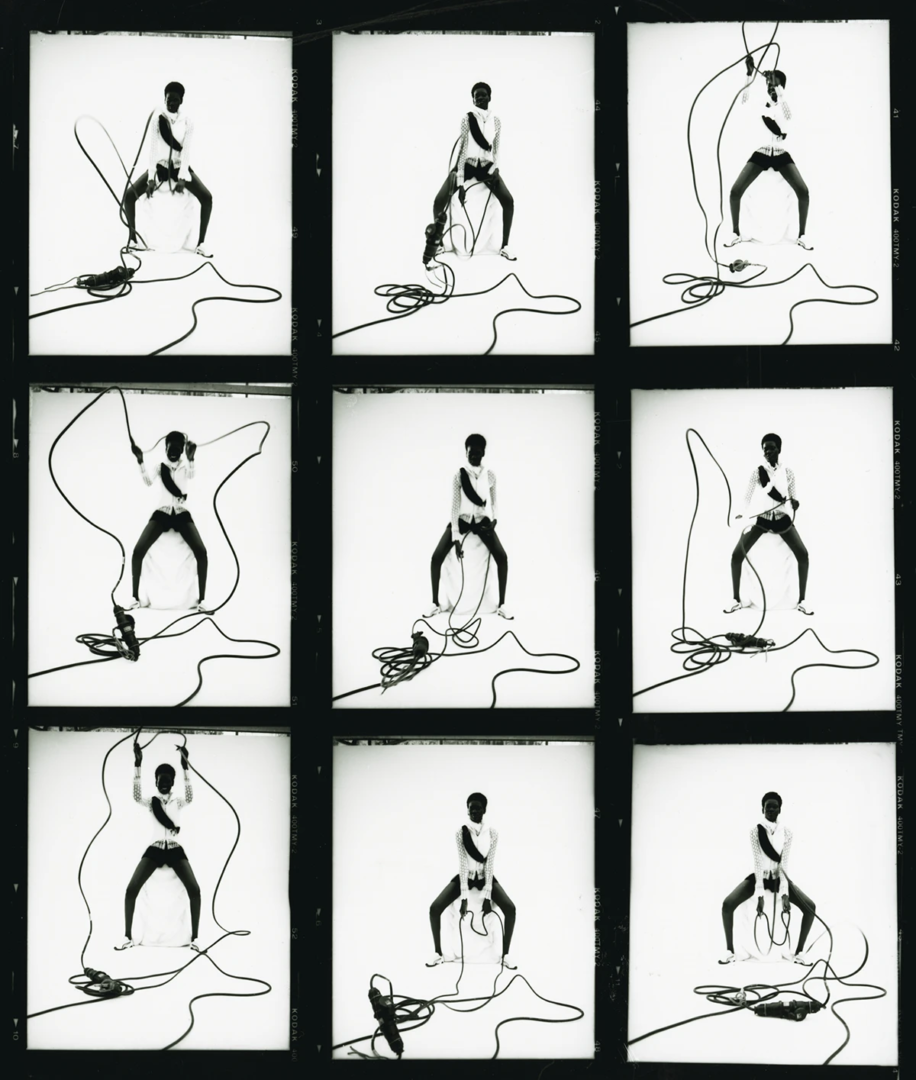

TEAM

Photographer and Director James Deacon, stylist Sophie Cloarec, casting Lucy Rogers, makeup Tina Khatri, hair Takumi Horiwaki, nails Megan Cummings using @Essie, light assistant Petros Poyiatgi, DOP Rami Hassan, stylist assistants Sadie Wyer-Manock and Isobel Atkinson, makeup assistants Elena Broccoli and Sasha Chudeeva, hair assistant Chinami Hamaguchi, video edit Jonathan Middleton, set and props Megan Mandevile, talents Nyagoa Diu and Lei Johnston @Select, Madison Warnford Davis and Holly Griffiths @PRM, Pien Laureijnssen @TheHive, Ivy Nicholls @Sway