Who said carbon is a market? When offsetting becomes upsetting

“Outsourcing the consequences of your own bad decisions is not the path.” The illusion of carbon neutrality: why climate change can’t be solved by buying carbon offsets and outsourcing responsibility

Interview with Tega Brain: Why carbon offsets may be delaying climate action instead of solving it

On a Monday afternoon, New York-based coding artist Tega Brain sat in her studio overthinking dominant responses to climate change. Carbon offsets: an economics system that allows businesses to compensate for their greenhouse gas emissions by supporting ‘carbon positive’ projects. As if these emissions never happened, because the damage was accounted for. As if money can buy anything – even a way out of climate change.

“Leaving aside that offsets are so boring and technical – this is the system underlying all the net-zero commitments we see from corporations and governments,” says Brain. “Yet there isn’t much critical scrutiny or cultural engagement with what offsetting or a carbon marketplace is. How do these registries work? Who’s running them? Who’s checking up on them? Who even knows if it’s working at all?”

How the carbon offset market works—and why many say it’s a climate scam

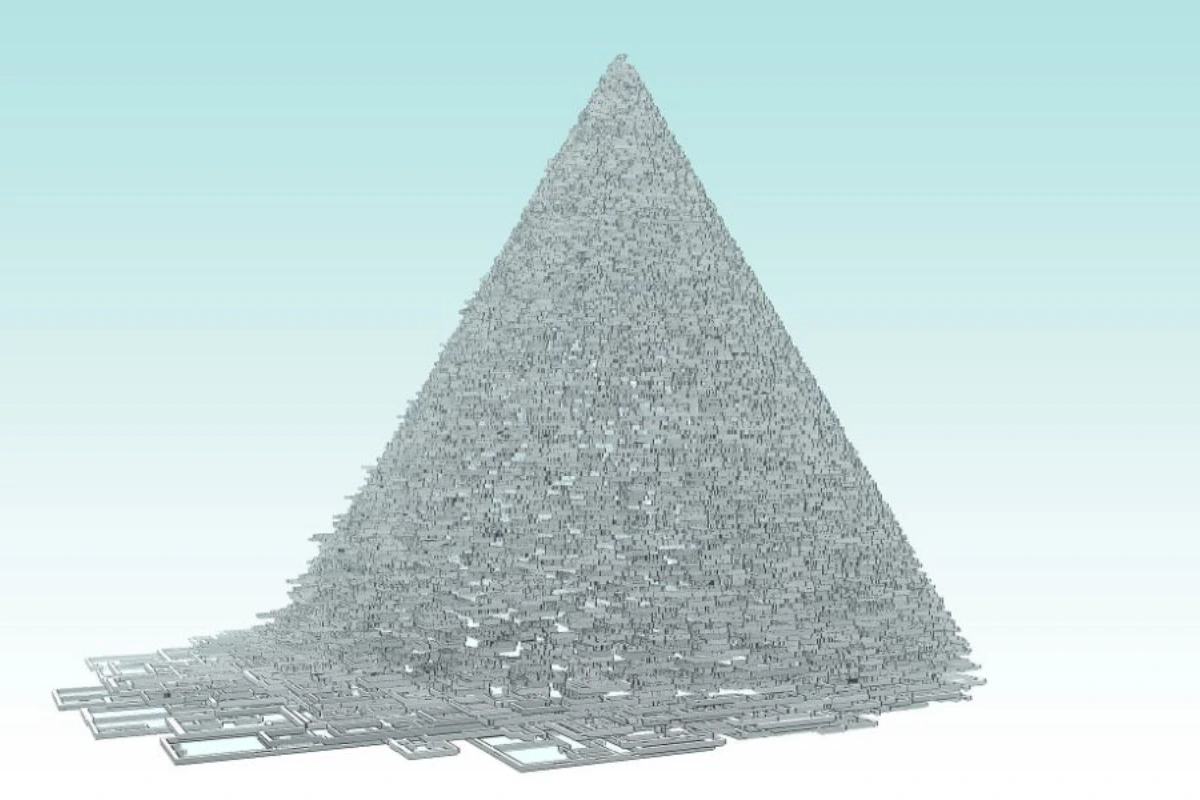

The carbon offset market is said to work like a scale: you put ‘bad’ emissions on one side, and supposedly positive climate actions on the other – be it planting a tree, preserving a carbon sink, or preventing new emissions elsewhere. To Brain, it’s a scam. She teamed up with fellow computing artist Sam Lavigne to think of better alternatives to deal with our growing carbon burden. Their ongoing project, Offset (2023), is a rebellious registry of alternative offsets composed of activists’ attempts to halt emissions using industrial sabotage.

The carbon benefits of these human disruptions can be calculated with a popular form of method from forestry offsetting: temporary carbon storage. This approach works by crediting landowners for keeping carbon in place. “It’s like saying: I won’t cut my forest down for now, but I will in ten years – and then financially benefiting from it”, says Brain, who consulted many carbon experts beforehand. “Every single one of them said it’s bullshit. That offsets are delaying the damage, keeping the earth healthier today while shifting the burden to future generations, under the assumption that they’ll have better technologies to deal with it.” When one expert told her she could apply the same flawed methodology to a group of protestors shutting down a plant, delaying the burning of coal for ten days, Offset was born.

Offset project by Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne turns climate protest into carbon credit calculations

Since 2023, Brain and Lavigne have been gathering submissions through their project website, conducting case studies, and gradually adding them to the Offset registry, complete with emissions impact calculations. The computing artists seek voluminous, infrastructural interventions that fit within the carbon accounting paradigm. Such as the Waorani Kawymeno people shutting down the Ishpingo oil field in 2023, or protestors disrupting crude oil flow from the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2017.

Being provocative, Brain explains: “We thought it was a massive oversight that activists who shut down infrastructure and prevent fossil fuel expansion aren’t credited for their efforts to ‘offset.’ If the logic of net zero is to measure and quantify all actions in terms of carbon, then surely, we should be taking all of them into account. What if political protest activities were remunerated? Wouldn’t we see much greater climate benefits?”

Can carbon offsets uphold colonial mechanisms? A critical look at Global North vs South responsibility

Seven sabotage cases are now complete and live. Their accompanying share of carbon credits will enter the market like any other offset – paired with an exhibition in September. The money will flow back to the protesters, whom Brain believes deserve far more recognition and dignity for their efforts. By ridiculing the system, she wants to provoke a deeper discomfort with carbon accounting. “Many people like me today are starting to wonder if they’re crazy: how is it legal that we’re still opening coal mines, yet shutting down a pipeline is illegal – and people are jailed for it?”

She adds that carbon offsets uphold colonial mechanisms. “Where is the acknowledgment that those of us in the Global North bear far greater responsibility for the crisis than anyone else, and that the burden of transformation should rest with us? It’s ridiculous to say: I will just pay the Global South, and they’ll have to figure out how to remove the carbon. They’ll need to change their agricultural practices and regenerate their forests. It’s unjust – and it’s not working.”

Interview with Barbara Haya: Why most carbon offset schemes don’t reduce real emissions

Barbara Haya, a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, has been picking apart carbon offset programs since 2003 – the year she jumped on a plane to India to pursue a PhD on one of the UN’s first offset schemes under the Kyoto Protocol. What she found on the ground didn’t quite match the promises: most of the projects weren’t actually cutting emissions.

“They were mainly paying developers who claimed they wouldn’t have continued their projects without the offset income – even though those projects had already been planned years earlier, with other subsidies and preferential tariffs. Because there was already interest in projects like wind, biomass and hydropower – both nationally and internationally. I saw plenty of those being allowed to register – even though the stories didn’t make sense.”

The carbon credit system is broken: Two major flaws you need to know

Over twenty years and many questionable carbon cases later, Haya sums up the carbon credit system with two major flaws. “The first thing,” she says, “is that the term ‘offset’ is a misnomer. Offsets don’t cancel out emissions. Production involves greenhouse gas emissions – no matter what is done outside the value chain. If you produce a cotton T-shirt, there are emissions associated with growing the crop. You can’t pay for reforestation somewhere else and say: we’ve undone the impact of growing cotton.”

The second issue is that many credits don’t represent real emissions reductions. “The market is hugely overcrediting across many project types.” Haya has spent years studying California’s offset program. “Three-quarters of the credits in the program come from so-called improved forest management, which allows forest landowners across the U.S. to generate credits simply for holding more carbon per hectare than a set average – as if they were about to cut their forests down to that average. That isn’t credible. Plus: half the forests were already above that average before the program even started.” Haya’s team used satellite data to compare participating lands with historical land use and with similar non-participating forests. The findings: “No clear fingerprint of the program” – in other words, no real change in forest management. Meanwhile, companies buy credits now and emit more than the legal cap, while the supposed carbon benefit may – or may not – happen decades later.

Protecting one forest won’t save the planet: the hidden problem of carbon leakage

Another issue is leakage. Protecting one forest doesn’t reduce demand for timber – it shifts harvesting elsewhere. One of Haya’s studies found that proper accounting for leakage would cut the credited impact by fivefold. Within the current methodology, the effect is averaged over a hundred years. “That only makes sense if what you want to do is keep credit prices low.”

How can a system this flawed continue to exist? Because nearly everyone involved benefits from excess crediting and exaggeration of the projects’ benefits, says Haya. Project developers want to maximize the number of credits for the same activities. Buyers want cheap credits. Third-party auditors – hired and paid by the developers – face a conflict of interest that encourages lenient reviews. Even registries – which issue and verify the credits – are paid per credit and compete for market share. Meanwhile, the system’s complexity and lack of transparency shield it from outside scrutiny. “Studying its effectiveness is (made) hard because a lot of the data is provided by the registries themselves. The carbon market is a perfect storm for poor quality – one that’s hard to remedy.”

Not impossible, she says. Take cookstoves – the fastest-growing project type in the offset market. A new methodology, currently under public comment at the UN, uses the best available science to monitor actual stove usage and translate fuel savings into tons of carbon saved. “Here is science making a difference – in policy and on the ground. Let’s first reduce internal emissions, and only then contribute to climate mitigation projects elsewhere. Let’s treat those as contributions – not offsets. Let’s invest directly in those programs. Cut out the middle people – too much money has gone into the pockets of brokers. We don’t need carbon to be a market.”

Alternative methods to carbon offsetting: Interview with Gallery Climate Coalition

There are other ways to pay our climate debt built up over the Anthropocene besides offsets. The arts sector is rapidly creating alternatives. Take the Gallery Climate Coalition (GCC), founded in 2020 to tackle the sector’s footprint, which non-profit Julie’s Bicycle estimates at 70 million tons of CO₂e (carbon dioxide equivalent). The organization steers two thousand galleries, museums, individual artists, and other art institutions globally toward environmentally responsible behavior and decarbonizing their share via so-called strategic climate funds.

Each member pledges to build one, based on a rough estimation of its (over)stock of emissions. Some feed their funds by charging a small premium on artworks; others budget a fixed percentage of annual revenues. Donations flow to frontline organizations with proven decarbonization strategies.

How Marianne Boesky Gallery and Nomad Exhibitions turned art into climate action

For example, Marianne Boesky Gallery in New York has seen 68,000 acres of land protected through donations from their climate fund to Art into Acres. Similarly, Nomad Exhibitions, a producer of sustainable touring exhibitions, translated its fund into helping to build a clean energy future in Africa. Sometimes, art organizations bond to grow bigger funds.

In 2021, over sixty galleries connected through the New York–based network Galleries Commit created one dedicated strategic climate fund for protecting high-biodiversity or Indigenous land. Their pooled resources consist not just of cash, but also artworks – which might be even more admirable. By using the products of our cultural sectors, from visual arts to the record industry, the arts can directly support climate justice.

Why climate funds are better than carbon credits for real environmental impact

According to community coordinator Lula Rappoport, money is better spent on climate funds than on carbon credits, exactly because budgets are allocated outside of the free market, with careful consideration of suitable frontline organizations. “Carbon offsetting is a passive act. You’re just checking a little box or sending some money to balance something out. While with strategic climate funds, you become an active participant in climate action through frontline organizations. I’ve seen arts organizations feel quite connected to the work they’re doing – it’s richer.”

What gets lost is the direct relationship with the company’s emissions – though one could argue whether there ever was one. Rappoport: “The thing with carbon offsetting is that it feels crystal clear. You can say: I’ve taken this flight, and a tree was planted instead. So, it’s fine. Nothing is that simple – especially when it comes to living ecosystems.”

The three biggest carbon challenges facing every creative organization today

Neither offsets nor donations from a fund can replace internal decarbonization goals. According to Rappoport, any creative organization that is ‘building’ something – be it an arts space, an event, or a fashion show – must deal with three carbon-hot issues: the building and its energy consumption, shipping, and travel, which often have much more room for improvement than an organization realizes.

You can look into sustainable energy tariffs, installing solar panels, and shipping by sea freight instead of air. Even climate control within buildings: most museums enforce restrictions around temperature, but the art world is starting to realize that these don’t need to be as strict as they are. Rappoport: “Restructuring the art world is a big ask, but you can ask: ‘Do I need to get this artwork to a client tomorrow, or could I suggest we take a couple of weeks and ship it by boat? And if we want the curator to see that artwork, does she have to fly on a private jet?’”

How Tate Modern, Hauser & Wirth and Thomas Dane Gallery are reducing emissions

These considerations often lead to considerable reductions in carbon emissions. In 2023, Tate Modern (along with the wider Tate estate) not only met but surpassed its carbon reduction goals – which wouldn’t have been possible without switching to green electricity and sustainably sourcing food in its restaurant-bar. In 2022, Zurich-based gallery Hauser & Wirth avoided emitting 200 tCO₂e (tons of carbon dioxide equivalent) by sending six exhibitions by sea instead of air. Similarly, London’s Thomas Dane Gallery managed to reroute shipments from the US and China, saving not only on emissions but also on costs: £24,000 that, in an ethical world, they would have put into their climate fund.

Fashion’s climate crisis: Why voluntary carbon offsets won’t fix a broken system

The same is true for fashion – a creative sector that, according to Bain & Company, is only 11 percent on track to meet its climate goals. Offsets alone won’t fix that, admits carbon expert Jos Cozijnsen. “In fashion, there are no clear legal caps like there are in industries such as maritime or aviation, and voluntary offsets face a lot of criticism.”

He advocates for a more direct approach that is ethically sounder: insetting. “Offsetting often means doing a project somewhere far outside your supply chain – because, technically, it doesn’t matter for the atmosphere where the reduction happens. With insetting, you organize impact within or near your production regions, creating a direct effect on your own operations. Apparel, in particular, calls for this kind of thinking, because of its fragmented, vulnerable value chains. With climate change, they need to get more resilient. It’s a personal industry – you’re dealing with farming, factories, local environments. Why not put your climate budget straight into those links?”

How insetting can help fashion brands reduce emissions within their own supply chains

Cozijnsen has been helping fashion businesses figure out what insetting can look like in practice – “it’s a relatively new approach,” he says. For example, a brand might work with affiliated local farmers to restore degraded land: planting cover crops that attract beneficial insects and improving soil health to boost carbon sequestration. The impact can be measured and verified on-site by a third-party auditor. H&M did something along these lines in 2022, in Indian cotton plantations, working with WWF. The project delivered quicker carbon results than expected, along with added benefits like lower cultivation costs and improved wildlife corridors – helping tigers and leopards move between protected areas. “Insetting may not get you any tradable credits or certificates,” Cozijnsen says, “but you do get primary, reliable impact data and a climate benefit that’s actually part of your own supply chain.”

While companies and governments must quickly navigate their way to real and just decarbonization, consumers get to continue their lives as usual, while pointing the finger – which isn’t entirely fair either, says Tega Brain. “We go on holiday all peacefully, thinking: If I pay the CO2 compensation for my flight, it’s fine. Offsetting gives us all a sense of control, as if we’re doing something meaningful.” She points at British geographer Sarah Bracking, who once said that much of climate financing functions as spectacle, with money playing a cultural role in that performance. It makes us feel like something is actually happening. Science says it’s not. Too much of our climate actions are still up in the air.