Restored coral can grow as fast as healthy reefs

A new study shows that coral reef restoration initiatives provide a temporary solution to restore compromised marine ecosystems – concrete climate actions for ocean preservation

Ocean preservation and climate action: coral restoration efforts undertaken in the Coral Triangle (CT)

The findings of a recent international study on the effects of coral restoration action give us good news for ocean preservation and climate action. In addition to increasing coral cover, these coral restoration efforts undertaken in the Coral Triangle (CT) area show that these restoration efforts can, within a short time frame, restore crucial ecological processes in addition to increasing coral cover, benefitting local marine life and the nearby coastlines.

«We found that restored coral reefs can grow at the same speed as healthy coral reefs just four years after coral transplantation», said Doctor Ines Lange, Senior Research Fellow at the University of Exeter, in the United Kingdom, in a press release. «This means that they provide lots of habitat for marine life and efficiently protect the adjacent island from wave energy and erosion». The lead author explained. «The speed of recovery that we saw was incredible», she says. «We did not expect a full recovery of reef framework production after only four years».

Understanding ocean preservation – What is coral reef restoration?

Ecological restoration is defined by the conservation organization the Society for Ecological Restoration (SER) as any action taken to aid in the recovery of a degraded ecosystem with the objective of attaining a significant ecosystem recovery in comparison to a suitable reference model.

The reasons why these restoration actions in the form of coral restoration are being implemented across the seas and oceans of the world are the anthropogenic worsening of the environmental conditions caused by climate change, the physical effects of storms and ship grounding, and invasive species.

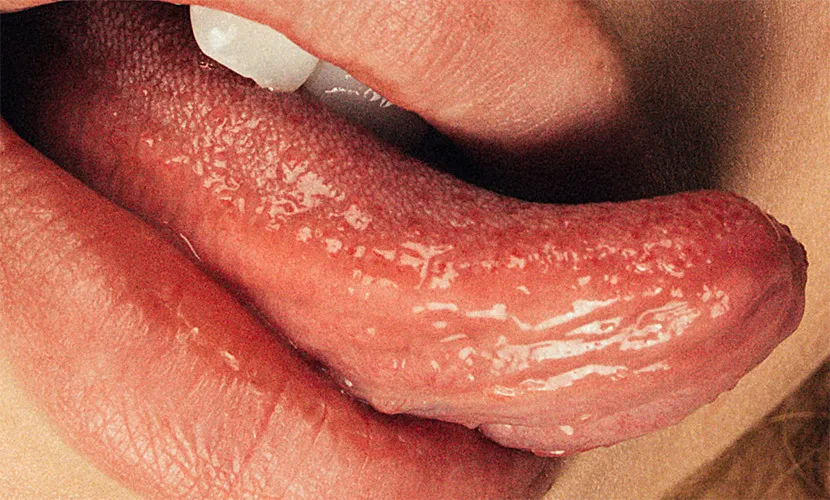

There are a plurality of restoration approaches addressing the restoration of lost coral habitats, such as direct transplantation and coral gardening. What makes these coral restoration projects feasible is the coral’s capacity to reproduce asexually. Thanks to this characteristic, individual corals, named polyps, can create colonies if they are grown in conditions conducive to their growth.

Reef Stars and coral restoration efforts in the Coral Triangle (CT) – climate action and ocean preservation

The study by the international team of scientists led by Doctor Lange was titled “Coral restoration can drive rapid reef carbonate budget recovery,” and it was published in “Current Biology,” the American scientific publisher Cell Press’s bimonthly biology journal, earlier this year.

The data used in the study was collected at the Mars Coral Reef Restoration Programme in South Sulawesi, Indonesia, one of the most significant restoration projects on the planet in collaboration with Universitas Hasanuddin, which is located in the nearby Indonesian town of Makassar. The Mars Coral Reef Restoration Programme is an initiative that seeks to restore reefs ruined by blast fishing thirty to forty years ago by using coral transplantation and substrate addition.

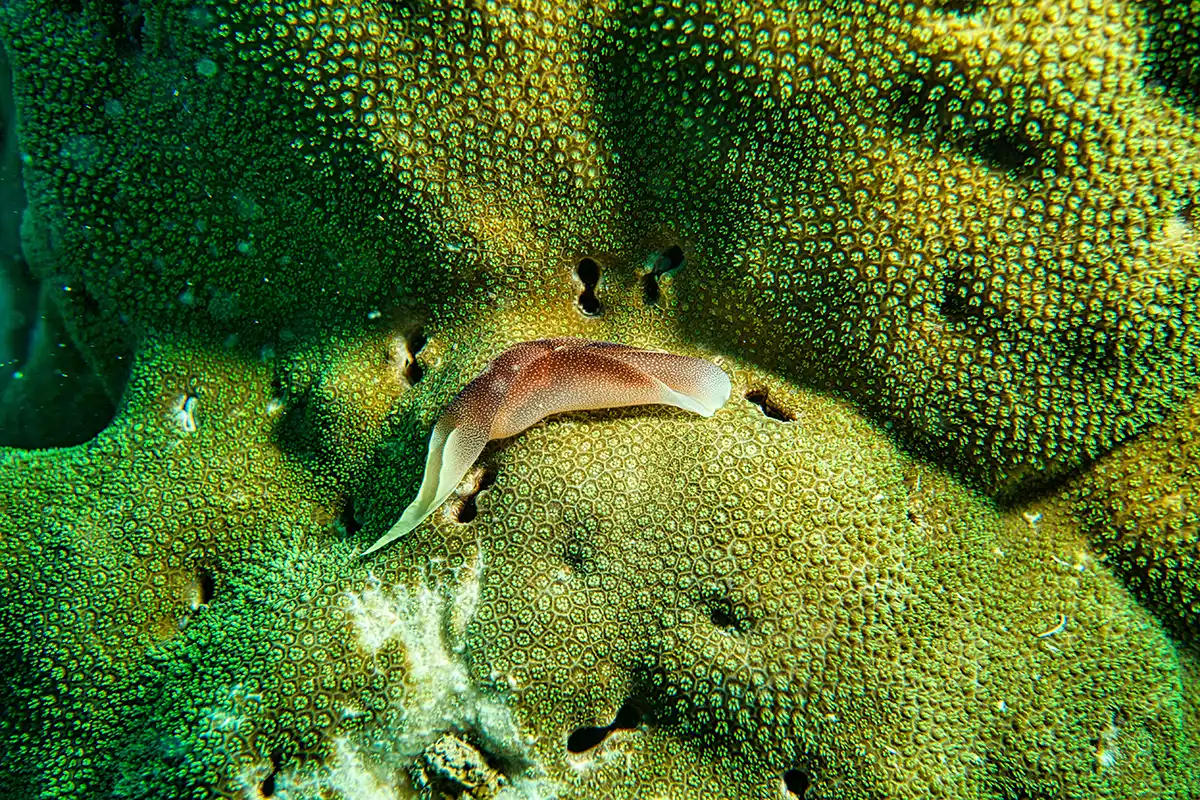

Within these sites, they replant healthy coral fragments onto interconnected, hexagon-shaped metal sand-coated frameworks called “Reef Stars,” which stabilize loose debris and offer a sturdy surface for the growth of this outplanted locally sourced coral. These structures are meant to become fully incorporated into the reef as the coral overgrows and engulfs them within a few years from their implantation.

The use of these tridimensional “Reef Stars” is a methodology fitting for the specific conditions of the examined sites. In these areas, coral larvae are not lacking, but the presence of mobile rubble impacts the survival of young corals, making a natural recovery of the sites without anthropogenic action unfeasible.

Ocean preservation in number – assessing the success of active coral restoration

This team of scientists assessed these restored reefs’ carbonate budgets to understand their trajectory. Carbonate budgets are a quantitative measure of a reef’s health and function state employed by scientists to determine the outcome of a coral restoration initiative.

«Corals constantly add calcium carbonate to the reef framework while some fishes and sea urchins erode it away, so calculating the overall carbonate budget basically tells you if the reef as a whole is growing or shrinking», Doctor Lange said. «Positive reef growth keeps up with sea-level rise, protects coastlines from storms and erosion, and provides habitat for reef animals».

The scientists conducted ReefBudget surveys at 12 coral restoration sites, part of the Mars Coral Reef Restoration Programme. Some of these had been restored for a handful of months, while others were restored up to 4 years ago. The reference sites were 3 healthy reefs and the same number of damaged ones. Doctor Lange’s and her team’s research marks the first reef carbonate budget trajectories carried out at coral restoration locations.

Good climate news – encouraging outcome from coral reef restoration efforts

This international study’s results are good news for these highly productive shallow marine ecosystems on the frontlines of climate change.

According to the analysis of the data collected through this research, transplanted corals proliferate, which helps carbonate production and coral cover recover. In their analysis, after a mere 4 years, the net carbonate budget increased to the level of healthy reference sites, thanks to high coral cover and fast coral growth rates. Established restoration sites have, in fact, some of the highest rates ever documented for reefs worldwide.

Restored coral reefs vs. healthy coral reefs

In the study, a few significant variations between healthy and restored coral reefs emerged. The regenerated reef communities have different compositions because branching corals were transplanted more frequently than other coral species. This is a recurrent practice in coral restoration programs all over the world, as it comes with several practical advantages. Because of this, the restored reefs might be lacking in biodiversity and habitat provision compared to healthy coral reefs.

As scaling up coral reef restoration efforts remains challenging, the sizable greenhouse gas emission reductions required to tackle climate change are still vital to preserving the coral reefs in the long term. Still, this study shows that extensive and multifaceted reef restoration initiatives provide a temporary solution to restore several critical ecosystem services provided by these marine ecosystems impacted by anthropogenic action on multiple levels. «As is so often the case, there is no one-size-fits-all solution, but we hope that this positive example can be used as inspiration for other reef restoration projects around the world», Doctor Ines Lange explained.

Ocean action and climate action go hand in hand – local management strategies on a warming planet

Coral reef restoration faces a significant challenge due to the increasing frequency and severity of climate-related stressors. Marine heat waves are expected to become more frequent in the coming decades, with projections of high-frequency severe bleaching by 2040-2050.

According to the researchers, coral reef restoration can be deployed strategically to address these issues. This approach can mean locating them in thermal refugia areas, places where transplanted corals are less likely to encounter lethal environmental conditions.

In addition, species selection should balance ecosystem value against the risk of future extinction which could be attained by transplanting species that are common in a location of a wide set of phenotypes.

Local stewardship should be ensured to reduce direct anthropogenic stressors, incorporating social-ecological frameworks into these projects, which lowers the risk of direct anthropogenic stressors.

«These results give us the encouragement that if we can rapidly reduce emissions and stabilize the climate, we have effective tools to help regrow functioning coral reefs», said Tim Lamont, a study co-author at the Lancaster Environment Centre, Lancaster University, UK.