Cross Cultural Chairs: The Chair as a Form of Identity and Belonging in the World

Matteo Guarnaccia’s project challenges the global standardization of chair design: postures, materials, and practices shared between artisans, designers, and local communities

The Chair as a Cultural Document

Cross Cultural Chairs began as a field investigation: eight months of travel through eight of the world’s most populous countries, focusing on one common object—the chair. Sicilian designer Matteo Guarnaccia built a comparative journey grounded in participant observation and direct collaboration with artisans, design studios, and local communities. The starting point was not form but cultural function. The chair is never a neutral object: it mirrors social models, hierarchies, and spirituality.

“Direct experience allowed me to develop a comparative methodology based on interaction with communities. Immersion highlighted postures, rituals, and meanings related to sitting that vary profoundly between cultures,” Guarnaccia explains. In some regions, chairs are absent from homes, replaced by mats or lower resting surfaces. In others, they symbolize modernity or remain as residues of colonial imposition.

Postures, Identity, Visual Codes

Each chair conceived during the journey becomes an anthropological portrait—a narrative device that conveys the complexity of everyday life rather than a mere stylization. “To avoid simplifications, I worked with artisans, designers, and local students. I sought out the smallest details that speak volumes: postures, materials, recurring shapes.”

Every choice—from materials to construction techniques—was dictated solely by context. This proximity-based approach, rather than theoretical mediation, ensures each object reflects the logic, resources, and habits of its place of origin. “Design followed the conditions on the ground: each chair arose from what was available, lived, and practiced in that territory, without distortion or abstraction.” From Japanese tatami to modular Brazilian seating, each prototype is rooted in its locale and conveys its symbolic tensions.

The Object as Translation Device

In its apparent simplicity, the chair becomes a mediator between different cultural codes. It does not merely represent; it translates. Every element—seat height, backrest angle, presence or absence of legs—encodes local practices and specific social contexts, never to be generalized.

In this sense, Cross Cultural Chairs works by subtraction: it imposes no form, letting environmental conditions, local customs, and available materials determine the outcome. The chair thus plays a dual role: concrete object and interpretive interface, visually conveying collective practices that other languages struggle to express.

Collaborate to Design, Design to Translate

At the core of the project lies collaboration—not a peer-to-peer exchange, but a making-based dialogue. “There was a practical conversation. Traditional techniques were applied in real time to new ideas. This made it possible to create objects that are both authentic and contemporary.”

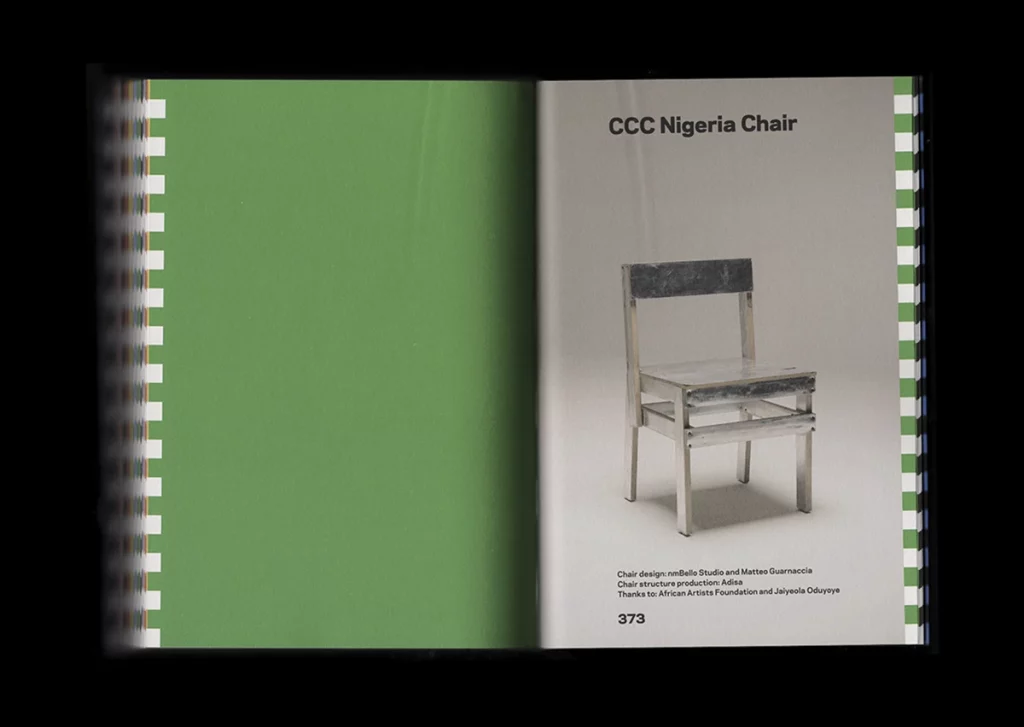

In each country visited, Guarnaccia activated a network of partnerships with museums, galleries, independent studios, and photographers. Construction always happened hands-on, in a situated design process. Among those involved were Studio Jose de la O, SP+Architects, Benwu Studio, NM Bello Studio, Mikiya Kobayashi, and Brunno Jahara Studio.

Localisms and Globalization: The Designer’s Role Today

The work questions the limits of globalization through an object often taken for granted in Western cultures. Yet half the world still sits on the ground. “Global design tends to flatten differences. But every object carries a way of life. That’s why it’s crucial to refocus on local specificities.”

In the countries visited—including India, Japan, Brazil, Russia, and Nigeria—the encounter with new generations of designers revealed a complex panorama. Some develop hybrid forms; others grapple with colonial legacies or indigenous material cultures. “Some adopt globalized postures; others remain anchored in local practices. This duality tells the story of our times.”

The Body in Space as a Relational System

The chair is both tool and sign—a prosthesis for the body and an index of social, familial, and religious codes. “In countries like Japan or India, the act of sitting is ritual. It’s not merely practical but a gesture that marks space, intention, and relationship.”

Sitting on the ground often means removing shoes, choosing loose clothing, inhabiting low-level spaces, and reducing architectural barriers. It implies a symbolic orientation toward the earth and others. In this light, Cross Cultural Chairs offers an unprecedented cartography of the body in space, interpreting furniture not only as utility but as a vessel of cultural language.

Seat-ing Exercises: Improvisation and Critical Reflection

From July 6 to 12, 2025, at Domaine de Boisbuchet in France, Matteo Guarnaccia will lead the workshop Seat-ing Exercises, a design and pedagogical extension of Cross Cultural Chairs. The studio focuses on material exploration and the improvised construction of seating using organic elements, production residues, and found objects.

“We work with waste materials, with minimal planning, leaving room for improvisation. But it’s not merely a creativity exercise: it’s also about reflecting on the meaning of everyday objects and how we can rethink them culturally.”

The workshop draws on Alexander von Vegesack’s collection of seats and saddles, offering a historical and contemporary reference archive. The saddle—as a nomadic object—becomes a symbol of movement, adaptation, and transport. In this context, the design gesture departs from industrial production to become a critical, conscious experience.

Toward a New Ecology of Design

Cross Cultural Chairs moves between artifact and archive, between performative design and ethnographic document. The project does not purport to offer answers but raises questions about identity, representation, and cultural appropriation. The object becomes a threshold between worlds, a lens for examination, a device for dialogue.

“With CCC I aim to show that design is not just aesthetics or functionality: it’s also a means to tell stories and spark critical thinking about the world around us.”

The intention is not to define replicable models but to convey what emerges from direct experience in the territories traversed. Here, the chair is not merely exhibition furniture but a social microcosm. Through its hands-on, collaborative, contextual creation, design returns to being a tool for reading reality, capable of recording the profound shifts of contemporary life.

Alessia Caliendo