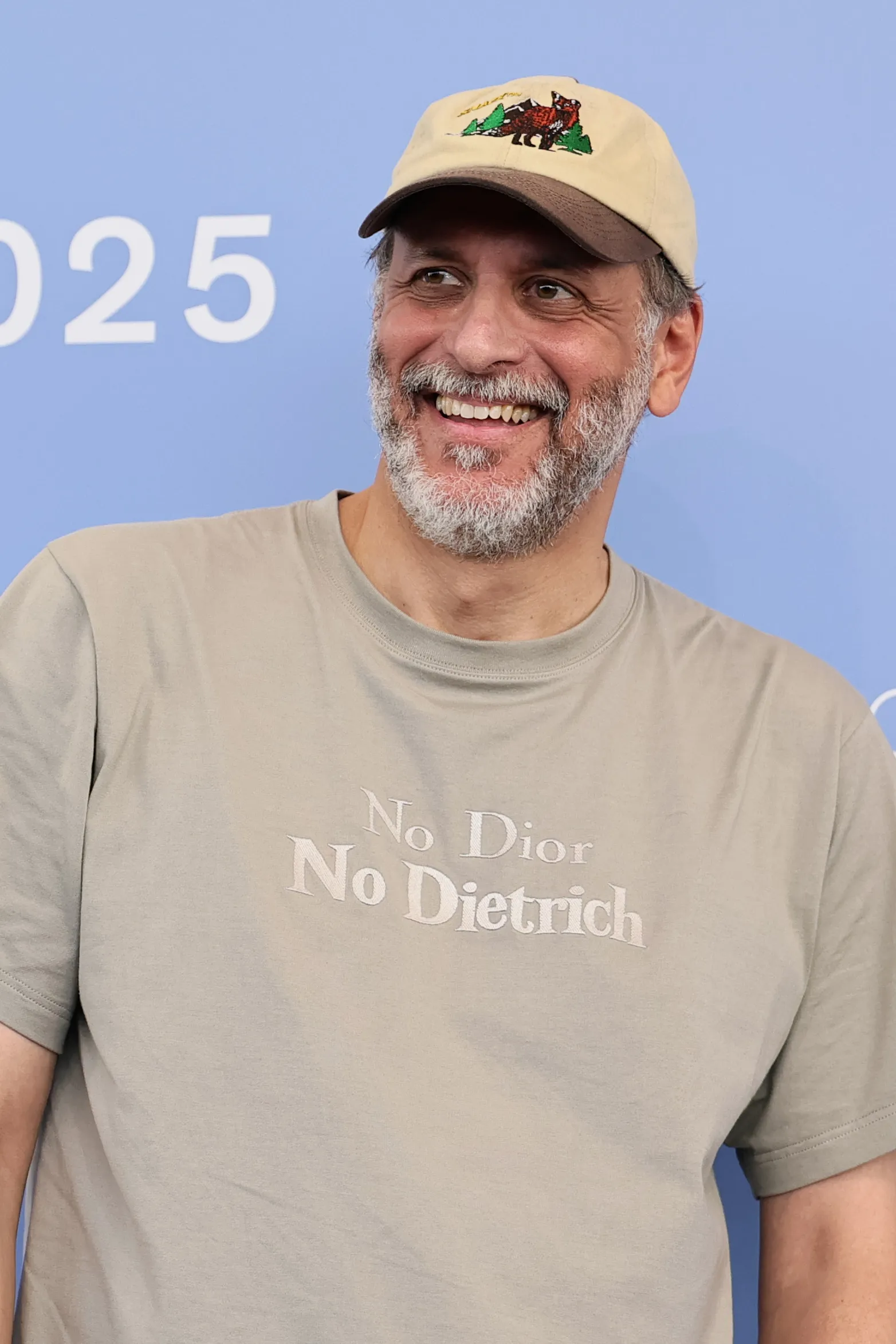

Daniel Kolodziejczak: I design the way an engineer might

Nothing hidden, no decoration that conceals the system – Daniel Kolodziejczak: a designer translating structure into marble, wood, geometry

This conversation is part of Lampoon’s column on “Talent, Taste, and Transformation” curated by Anouk Jans.

From ateliers in Paris to workshops in Pietrasanta and São Paulo, Daniel Kolodziejczak builds furniture as architecture — structures defined by weight, balance, and craft. His career moves from jewelry to interiors to large-scale design, each stage refining a language of visible construction and material honesty. In this conversation, he retraces the steps of that path: the studios, collaborators, and processes that shaped his way of working, and the meaning of permanence in contemporary design.

This conversation is part of Lampoon’s column on Talent, Taste, and Transformation curated by Anouk Jans.

AJ:You began in jewelry before moving into interiors and furniture. What prompted that shift?

DK: “Jewelry was my starting point in fashion. I began working with local ateliers in Paris around 2010, producing limited pieces in brass and bronze. Jewelry taught me construction — the discipline of proportion and precision. A clasp or hinge has to be engineered as carefully as it is designed.

In 2017, I started translating that same approach to interiors. I worked with private clients in Paris and London, developing custom furniture and lighting. Interiors introduced scale and atmosphere — how materials interact with light, temperature, and architecture.

Furniture became the meeting point between those two worlds. It carries the refinement of jewelry and the permanence of architecture. My first furniture line was presented in Milan in 2020: the Antechamber collection. Each year since, we’ve developed a new “room” — 2021 was the study, 2022 the living room. The process is sequential, like constructing a house piece by piece.”

AJ: You often speak of design as structure. What do you mean by that?

DK: “Every joint, every connection must be visible and resolved. I design the way an engineer might: nothing hidden, no decoration that conceals the system. The goal is permanence. When I work with marble, the grain dictates the form. When I work with wood, I look for density, for silence in the surface.

The Copan sofa from last year’s collection, for example, came from studying the curves of Oscar Niemeyer’s architecture in Brasília. The base is bronze; the structure is visible; the upholstery is minimal. You can read how it’s built.”

AJ: What materials define your current body of work?

DK: “Marble, wood, and metal. The marble comes from Carrara, Verona, and sometimes Minas Gerais in Brazil. The woods are usually oak or walnut, depending on tone. Metals are mostly bronze or brass — I prefer alloys that change over time. Each piece carries traces of its making; oxidation and wear are part of its identity.

The connection to jewelry remains: each component is finished by hand, polished to a level closer to ornament than furniture. The process is slow. A dining table can take three months from first sketch to installation.”

AJ: How has travel informed your projects?

DK: “Travel sets context. I’ve produced in Italy, France, and Brazil, each for different reasons. Italy is about precision, the technical tradition of furniture. Brazil offers freedom in form and material. France allows a dialogue between the two — rigor and experimentation.

The light in Brazil changed my perception of color and shadow. The Italian marble industry refined my sense of proportion. Each location leaves a technical imprint rather than a stylistic one..”

AJ: Do you see yourself as part of a design lineage?

DK: “Yes, in terms of continuity of craft. My references are Diego Giacometti, Jean-Michel Frank, and Brazilian designers such as Sérgio Rodrigues. They all combine sculpture, structure, and domesticity. Their work reminds me that design evolves through artisanship, not trend.

At the same time, our generation has access to materials and digital tools they never had. We can work faster and share more openly, but the challenge is maintaining depth. My approach is to slow it down again.”

AJ: How would you define taste in your work?

DK: “Taste is the sum of decisions over time — what you accept, what you reject. Mine oscillates between rigor and excess. I’m drawn to contrasts: smooth and rough, cold and warm. The interiors of Pompeii, for example, fascinate me for that reason — geometry and decay coexisting.

In practice, taste becomes editing. Hundreds of prototypes are made before a piece feels resolved. I stop when the object no longer tries to impress, when it simply belongs.”

AJ: What are you working on now?

DK: “The next collection continues the idea of a house. We’re developing a bedroom series — smaller, more intimate pieces. There’s also an exhibition planned for next year in Paris, focusing on the process: sketches, molds, and prototypes.

I’m also returning to jewelry on a small scale — creating handles and hardware for furniture, turning a hinge into something collectible. It closes the circle from where I began.”

AJ: What does longevity mean to you in design?

DK: “Longevity is built through use. A chair or table must improve with time. If the surface changes color, if the metal darkens, that’s a record of life around it. The goal is not to preserve the object as new, but to allow it to mature.

Design, for me, is a language of permanence — not to resist change, but to hold it.”