Jonathan Anderson, Dior, and the British Cultural Scratch

Dissidence, irony, and controlled provocation. This is the British contribution to a house that more than any other embodies wealth, heritage, and symbolic power.

Jonathan Anderson’s scratch at Dior

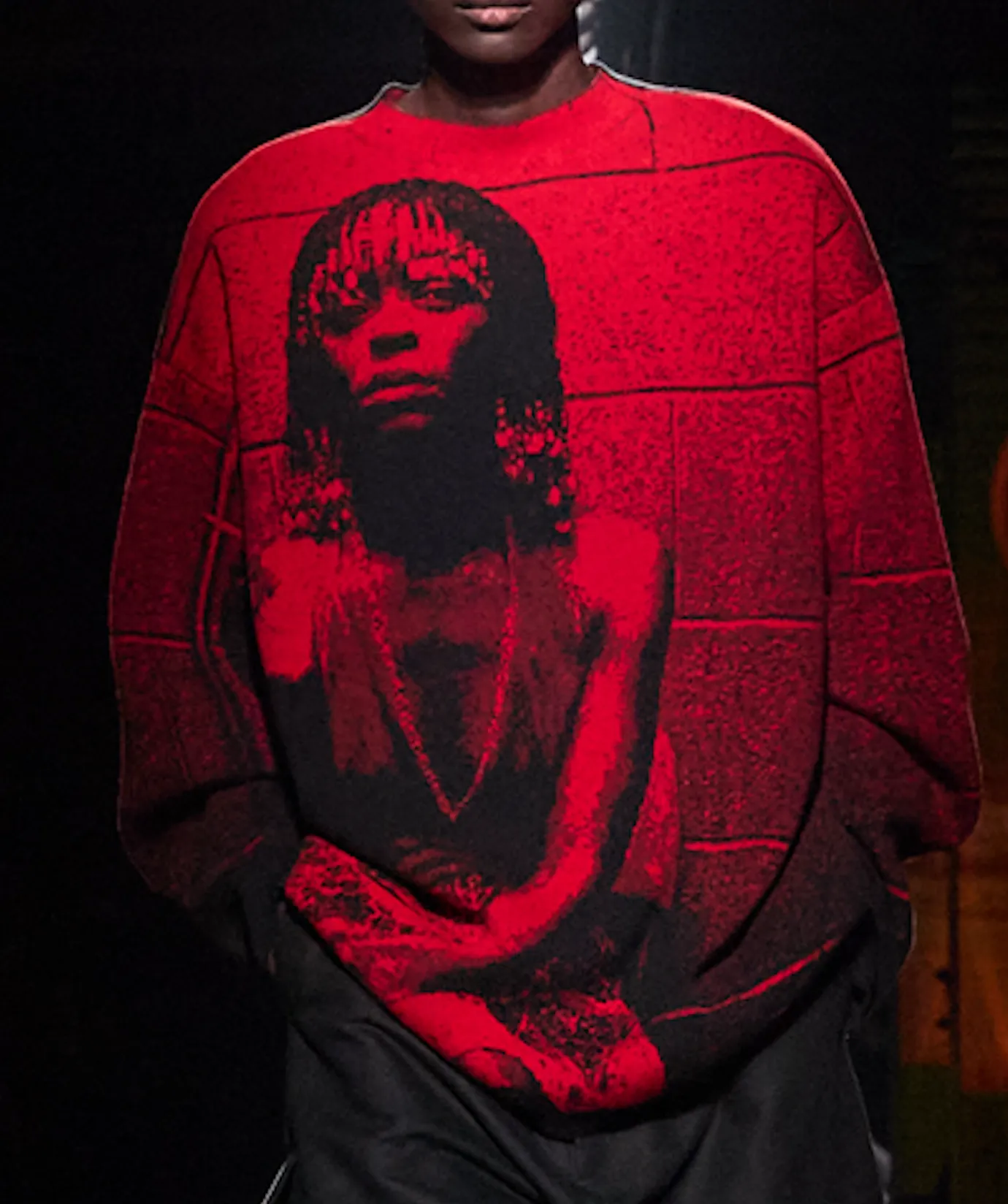

The intention is friction. Jonathan Anderson’s men’s show for Dior is designed to unsettle. A scratch rather than a caress. The effect is amplified by timing: Paris follows Milan, and the contrast is immediate. Milan speaks the language of strategy, sell-through, legibility. Paris shifts tempo. With Dior, the conversation changes.

Anderson greets guests with restraint and politeness after the show. Before that, on the runway, the aim is different. To make you raise an eyebrow. Everything appears refined, controlled, elegant. Yet the underlying mechanism is irritation. The show wants to resist immediate approval. You think you dislike it. Later, it returns. In the evening, at night. The next morning, the resistance weakens. The work settles. What disturbed begins to attract.

Anderson and the British designer lineage

Anderson is British, and he claims that lineage openly. A lineage of designers who never aimed to make “beautiful” clothes. They wanted to press, cut, disturb. Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen, John Galliano. Isabella Blow as catalyst and amplifier. Anderson positions himself within this tradition with clarity.

British humor is dry and oblique. A joke that lands late. Color sharpens under permanent rain. A yellow wig. Sequins. Epaulettes and fringes borrowed from military fantasy already filtered through 1970s rock culture. Cropped jackets sitting above the waist. Aggressively printed trousers. Bombers that lean toward club culture.

Then tailoring enters. A long coat. A sculpted suit. Pieces anyone would want to wear. The tension lies in styling. Garments no one would choose alone are paired with garments everyone desires. The reference to Paul Poiret is readable, but not essential. Anderson’s work stands without annotation.

Milan and Paris, two systems

Paris and Milan operate on different logics. Paris performs indifference as power. A city of hostile taxi drivers and young men convinced of their own allure in every café. Shirts open in January, regardless of rain. Everything is staged for vanity. Even decay becomes part of the pose. Paris places you on a stage whether you ask for it or not.

Milan works differently. Milan works. Prada may celebrate imagination, but the reminder follows: these are clothes meant to be bought. Fly high, but know how to land. Life happens behind gates and courtyards. Snobbery is coded as understatement. There is little decor, but strong design. Books are meant to be read, not displayed. In Paris, books are large, visual, and decorative, placed on consoles and coffee tables. Dior carries Versailles and Rococo in its DNA. Milan carries modern rationalism.

Jonathan Anderson, Dior, and institutional wealth

Jonathan Anderson at Dior brings a cerebral British culture into the most explicit symbol of global luxury. Dior is gold. Dior is excess without apology. Dior allows itself arrogance, hauteur, accumulation. By definition, luxury has no internal limit.

The house is led by an imperial figure. It stands as a Parisian emblem capable of ignoring history itself. Today, this institution is shaped by a tall English designer with tired blue eyes, hands in his jeans, a soft-spoken presence that masks control.

Anderson is among the most respected designers in the industry. At Loewe, he destabilized Spanish craft, pushing it into unfamiliar territory. In his own label, he built a wardrobe where garments coexist with memory, pop references, and private jokes. The “I Told Ya” T-shirts with Luca Guadagnino. “Drink Your Milk,” echoing Fellow Travelers, Matt Bomer, Jonathan Bailey, and the doubled body of dancer Ivan Ugrin. A phrase repeated until it turns uneasy. Milk as innocence, threat, excess. Even desire is treated as material.

At Dior, the question is structural. How will this density of references—high and low, ironic and severe—interact with markets where luxury demands composure, embroidery, and formal perfection? Asia. The Middle East. Systems that value control over disruption.

Jonathan Anderson and craftsmanship

Anderson is a designer of applied craft. Many of his ideas resist industrial execution. They require hands. Not because of nostalgia, but because machines are insufficient. His imagination exceeds available processes.

In a moment when artificial intelligence is framed as a challenge to human creativity, Anderson insists on excess, difficulty, and manual intelligence. His work asks for time, labor, and risk. It remains open-ended.

What comes next matters. The industry watches, even if much of the press no longer does. Journalists have largely been replaced by proximity seekers and image brokers. Opinions give way to access. Presence replaces critique.

Between Milan and Paris, the work persists. It scratches. It stays.

Carlo Mazzoni