Hygiene and the fracture of modernist architecture, Ignazio Gardella never designed through purity

Dispensario Antitubbercolare: Ignazio Gardella responded to political and hygienic pressures with calibrated disobedience, embedding spatial misalignments into a structure born of regulation

The origins of the Dispensario Antitubercolare Ignazio Gardella, Alessandria: public health architecture under fascism

Ignazio Gardella designed the Dispensario Antitubercolare in Alessandria between 1934 and 1938, at a time when fascist Italy was launching large public health campaigns to control tuberculosis. These programs promoted the construction of dispensaries—small outpatient facilities meant to screen and monitor the population. Gardella’s building was one of the clearest products of this policy and reflects the political, social, and medical concerns of the period.

The commission came to Gardella under unusual circumstances. It followed the death of his father, Arnaldo Gardella, a respected engineer in Alessandria. Ignazio, still in his twenties and newly graduated, inherited the assignment even though he had no formal architectural training. The program was already defined in detail: the clinic had to meet strict hygiene and health regulations. It needed separate routes for male and female patients, sunlight in every treatment room, and surfaces that could be washed and sterilized. These requirements deeply shaped the design and gave Gardella a framework in which to work.

Ignazio Gardella’s early modernism: asymmetry, resistance, and material economy

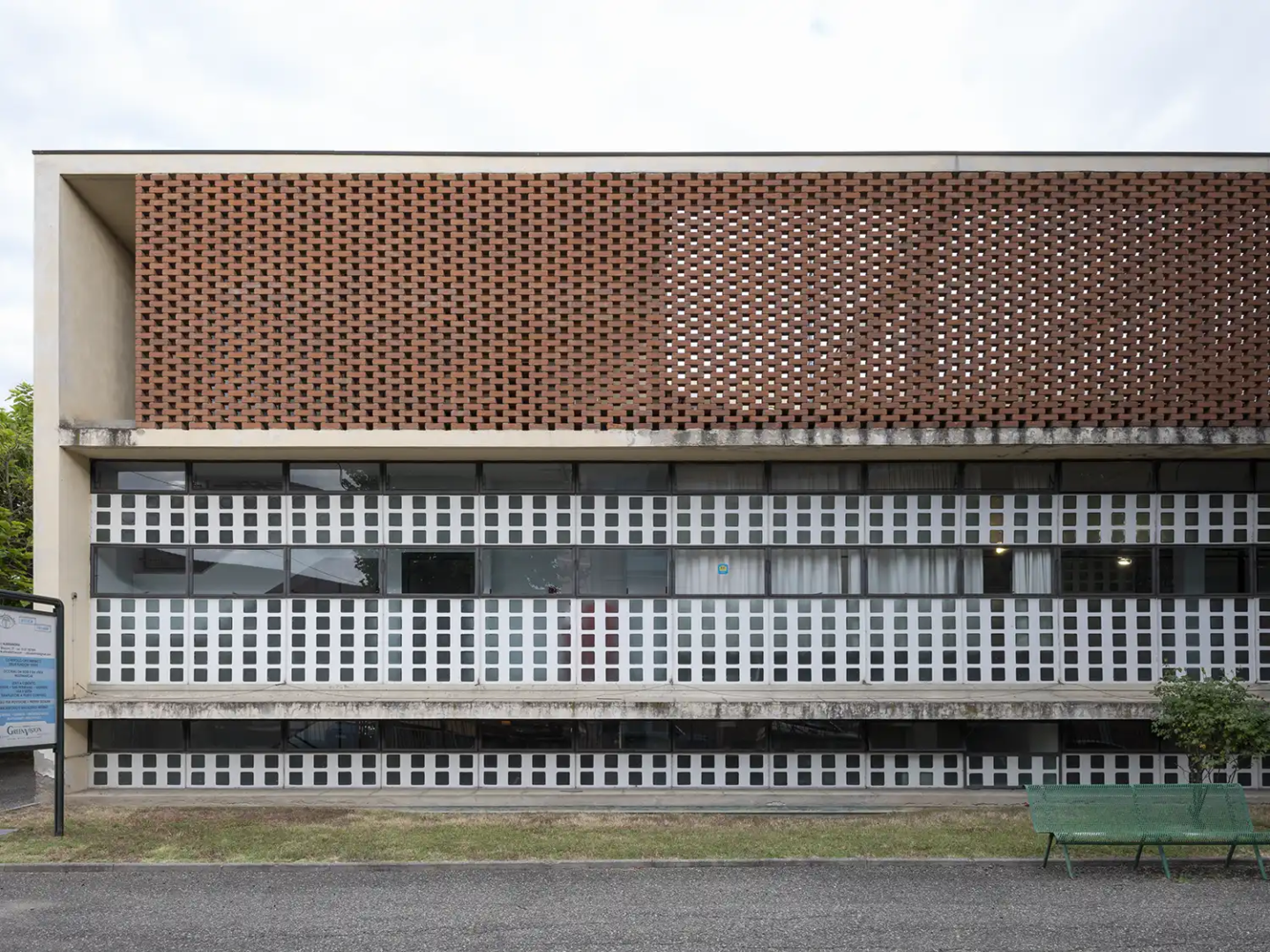

The building took the form of a 35-by-35-meter cube, with two floors above ground and one below. The structure faced east to west and relied on a clear, rational grid that guided both the plan and the elevations. Circulation followed an ordered system of axes. At the center, a main staircase and a waiting area received daylight from above through a skylight made of glass blocks. Load-bearing pillars gave rhythm to the spaces, while the non-structural outer walls allowed for wide horizontal windows and translucent surfaces. Ventilation was constant, and the arrangement of openings created both light and privacy.

Despite the strict medical regulations, Gardella introduced subtle gestures of freedom. He questioned the symmetrical division and gender separation imposed by the health authorities. His first design included an off-center entrance, which would have disrupted the rigid symmetry and encouraged a more fluid use of public space. The authorities rejected this proposal and required a central access point. Gardella adapted, yet the final building preserved traces of his initial idea: the circulation paths remained slightly misaligned, and the internal rhythm resisted perfect balance. Through this quiet shift, Gardella managed to challenge the official order without open defiance.

He also experimented with materials in ways that anticipated his later work. The façade combined brick, glass block, and steel, creating a dialogue between solid and transparent surfaces. A visible steel beam cut across the front, breaking the monotony of the grid. Inside, curved iron handrails ran along walls covered in glazed tiles. The building mixed industrial precision with handcrafted detail. These choices reflected economic necessity, since Italy was facing material shortages, but they also revealed Gardella’s early interest in combining efficiency with warmth and imperfection.

From decay to restoration: Gardella’s return to the Dispensario

The dispensary was completed in 1938 and opened the following year. For two decades, it functioned as a tuberculosis screening center, serving as part of a nationwide effort to reduce infection rates. In the 1950s, as the incidence of tuberculosis declined, the facility was converted into a general outpatient clinic. Its modern layout adapted well to new uses, though maintenance became irregular.

By the 1980s, the building had fallen into decay. The plaster peeled from the walls, graffiti covered the façade, and pigeons filled the stairwell. Vegetation grew in the joints between concrete slabs. For many locals, the dispensary seemed abandoned and forgotten, another relic of the rationalist era. Yet for Gardella, it remained a deeply personal work—his first built project, the place where his architectural thinking began.

When the municipality of Alessandria decided to restore the building in the early 1990s, Gardella was invited to oversee the project himself. Now in his eighties and widely recognized as one of Italy’s leading architects, he approached the restoration as both a professional and personal return. This time, he reinstated the off-center entrance that had been rejected in the 1930s. He simplified the internal configuration to improve circulation and carefully studied the original colors, recovering traces of light yellow, pale blue, and white hidden under layers of institutional paint. While he replaced fixtures and modernized the systems, he preserved the essential structure and character of the building. The restoration was completed in 1996, six decades after the original construction.

The legacy of Ignazio Gardella: beyond rationalism and beyond style

Throughout his long career, Gardella resisted stylistic rigidity. He worked within constraints—political, social, and technical—but turned them into creative opportunities. His work evolved from fascist-era commissions to post-war reconstruction and later to university buildings and office complexes during Italy’s economic boom. He moved across movements—rationalism, post-rationalism, and even brutalism—without adhering fully to any of them.

Born in Milan in 1905, Gardella trained as an engineer, and this background shaped his precise yet flexible design method. After the Alessandria dispensary, he designed hospitals, housing blocks, churches, and public buildings. In 1947, he joined the CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne) but left quietly a few years later when he felt Le Corbusier’s principles had become too rigid. During the 1950s, he collaborated with Franco Albini and Ernesto Nathan Rogers, two figures who shared his interest in combining rational structure with emotional expression.

One of his best-known works, Casa Tognella (1947–1952), also known as Casa al Parco, stands on Via Marchiondi in Milan. The building combines a brick base with projecting concrete balconies and finely detailed metalwork. It was among the first post-war Milanese buildings to engage with the urban environment without resorting to imitation of historical styles. Its modular structure, open façades, and crafted details anticipated the tone of Milan’s architectural renewal.

Later, Gardella designed the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Genoa (1975–1989), a complex that climbs the hillside in a sequence of terraces and concrete forms. The building breaks the rules of strict rationalism. Corridors expand and contract; windows appear where needed rather than for symmetry. Critics described it as unresolved, but Gardella never responded. For him, architecture was not about resolution but negotiation—between order and freedom, between plan and experience.

A workshop, not a studio

Gardella’s professional life remained intentionally small in scale. He avoided large competitions and preferred to work with recurring clients: regional health authorities, universities, and municipalities. His office in Milan functioned more like a workshop than a corporate studio. Projects developed slowly, through dialogue, drawing, and model-making. He valued precision, but also the unpredictable outcomes that came from collaboration.

Gardella died in 1999 at the age of ninety-four. By then, the dispensary in Alessandria had returned to full use as a public health facility. Locals now refer to it as the “Poliambulatorio Gardella.” It serves around four hundred patients each day. Few visitors know its history—the rational grid, the hidden asymmetry, the story of its decay and revival.

The building is not a monument. It is a fragment of a healthcare program, transformed across generations yet still alive. The dispensary stands as a quiet reminder that architecture can exist between discipline and freedom, between rule and invention. Gardella never tried to resolve that contradiction. Instead, he built it into the walls.