The Bi culture: does bisexuality exist?

From Seventies bisexual activism to the erasure of those living outside straight and homo definitions – Pillion, Euphoria and other movies and TV series explore how visibility can question fixed notions of desire

The Culture of Being Bisexual – bisexuality exist? A definition questioned

Bisexuality exists – yet it is constantly questioned. The term describes attraction to more than one gender, but its recognition remains unstable. In public discourse, bisexuality oscillates between curiosity and denial.

According to Ipsos Global Advisor (2024), seventeen percent of Gen Z respondents worldwide identify as non-heterosexual. In Italy, fewer than four percent openly define themselves as bisexual. The distance between identification and expression reveals a cultural gap: visibility does not equal acceptance.

Within the LGBTQ+ community, bisexual people often describe a double marginalization – erased by heteronormativity and distrusted by the queer movement. Psychologist and researcher Julia Shaw, in her book Bi. The Hidden Culture, History and Science of Bisexuality, defines this as a ‘social invisibility mechanism’: a tendency to simplify attraction into fixed categories, refusing the middle ground.

Bisexuality: a political history of denial – Robyn Ochs and Lindsay River

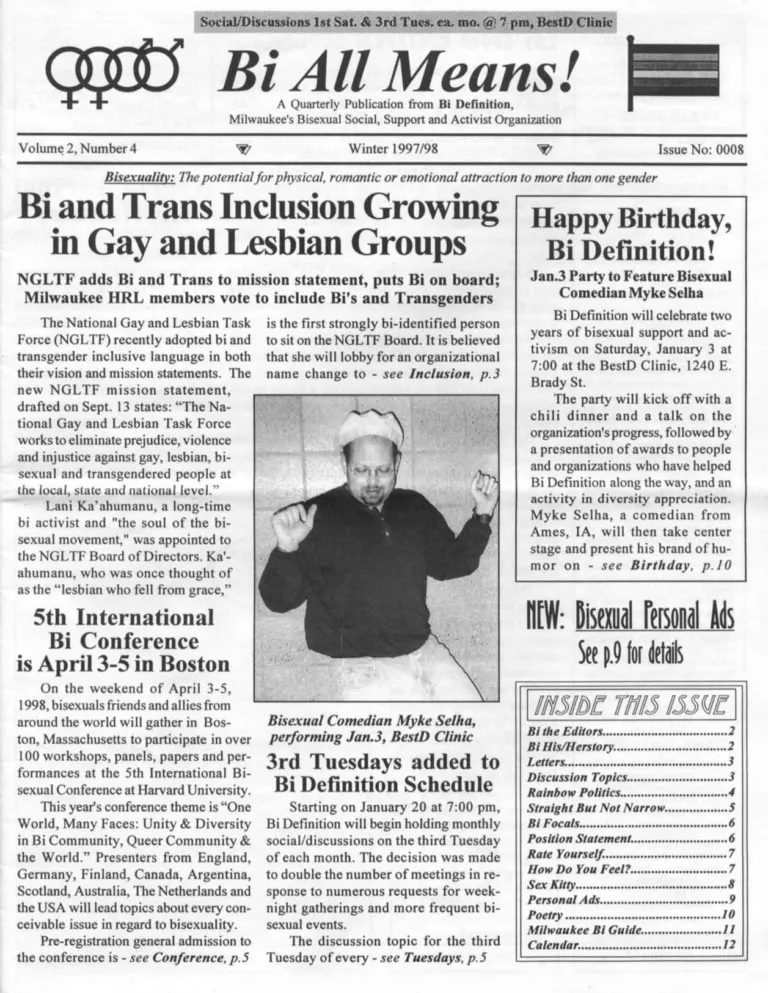

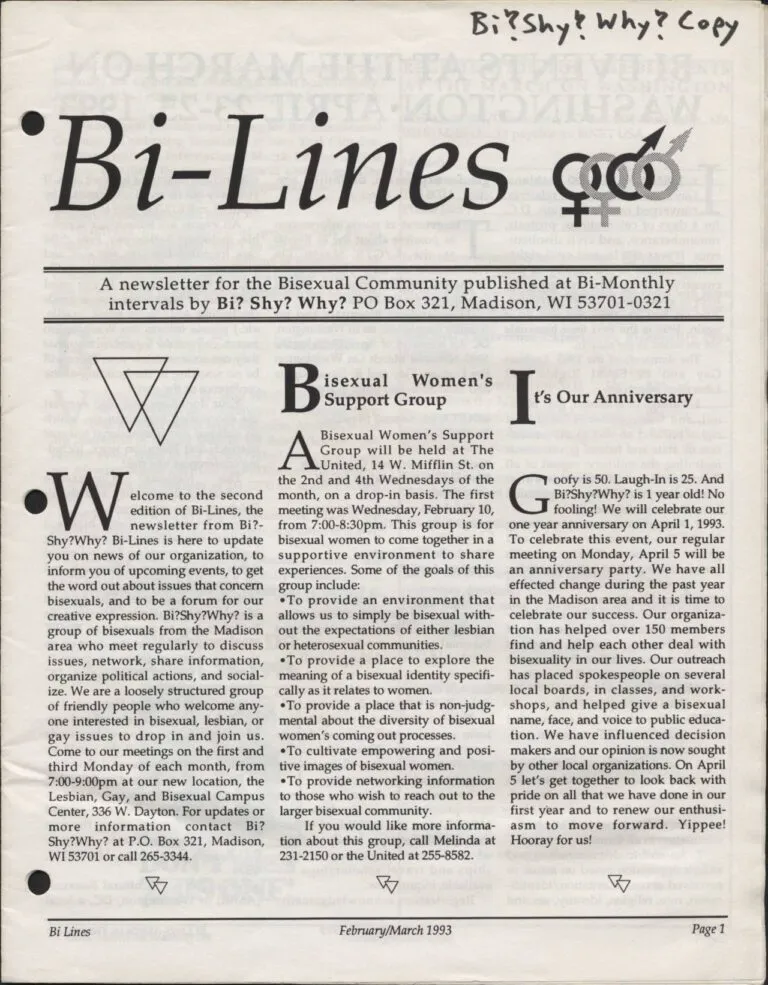

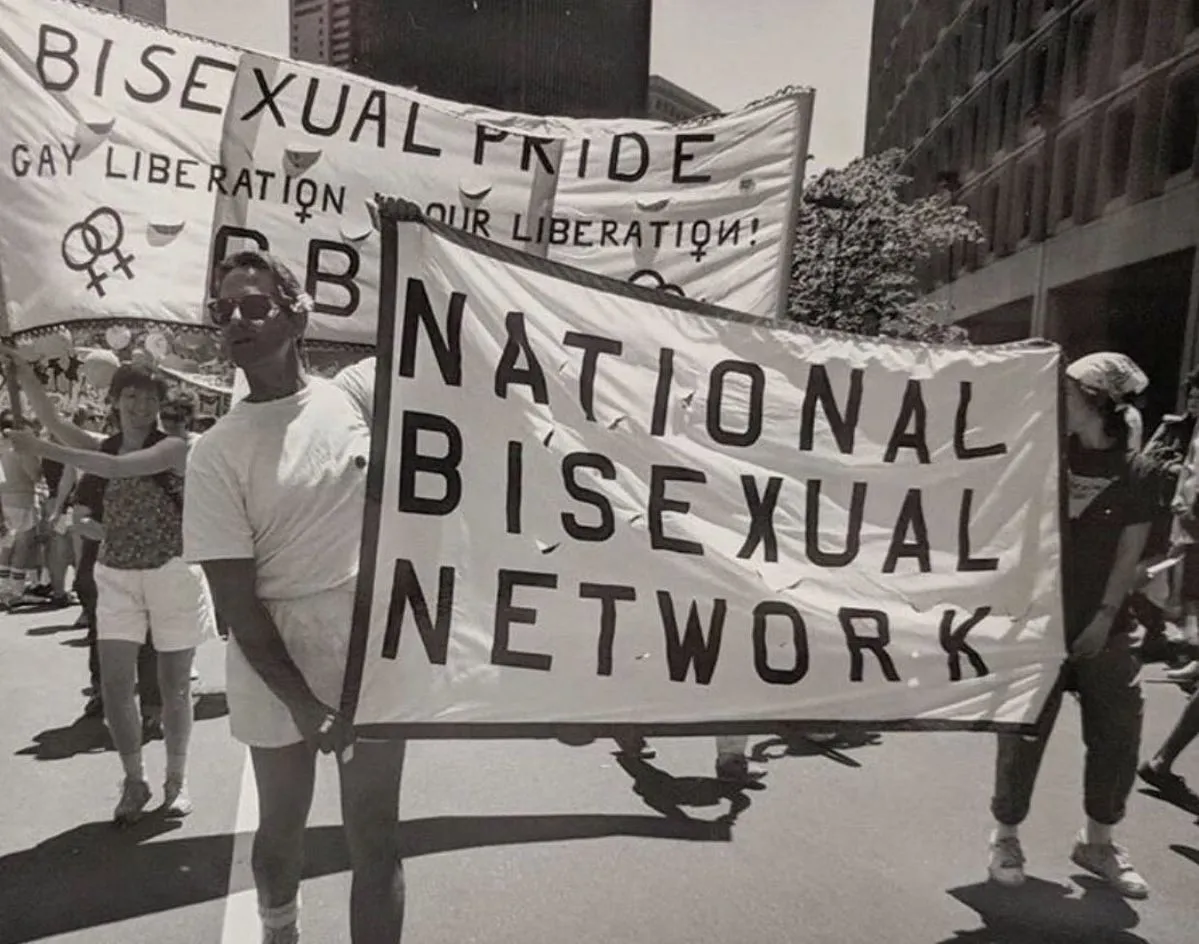

The history of bisexuality is also the history of its erasure. The word appeared in late nineteenth-century medical literature to describe ‘dual attraction’, but it took on political meaning only in the nineteen-seventies.

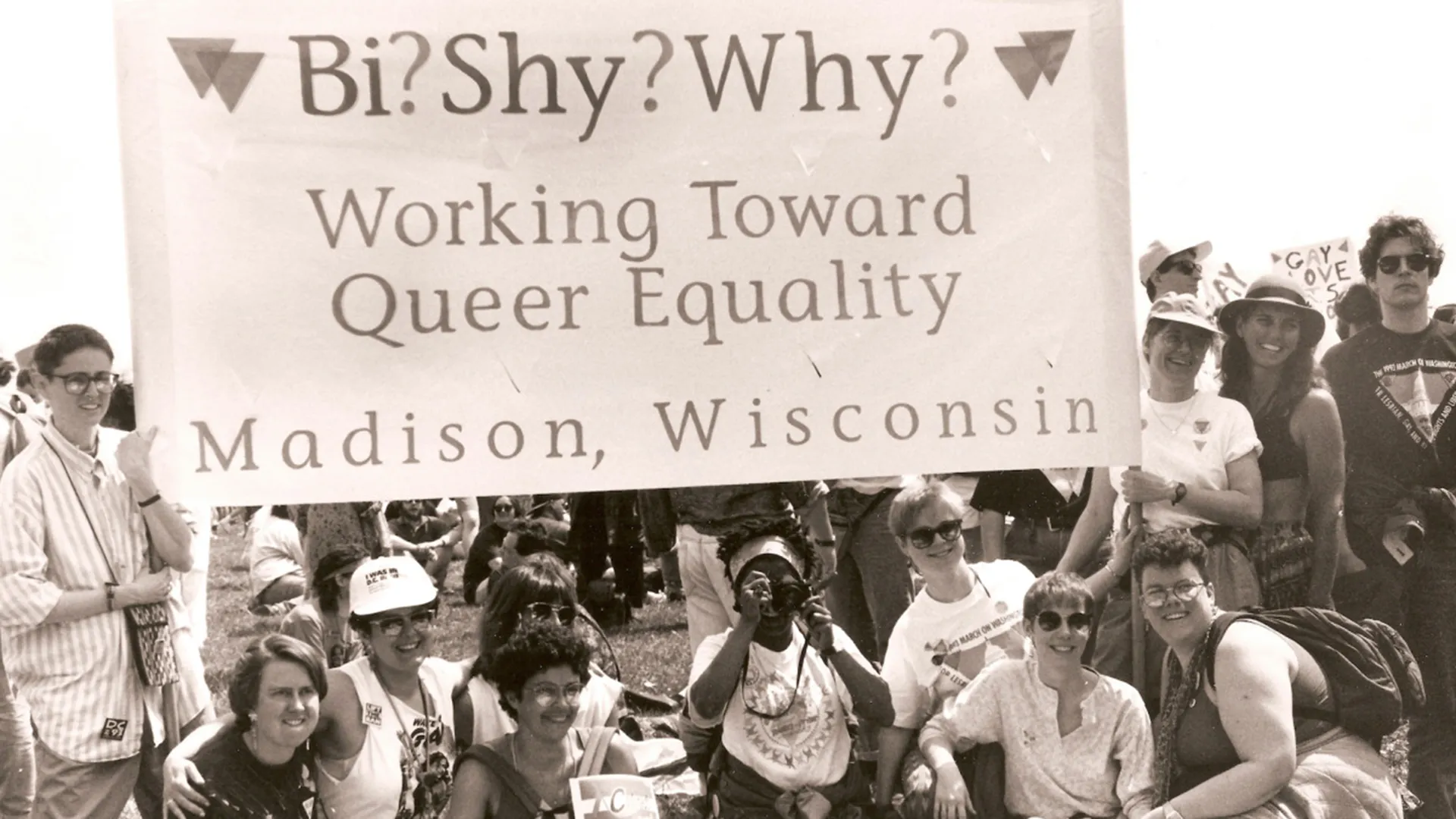

Activists such as Robyn Ochs in the United States and Lindsay River in the United Kingdom tried to establish bisexual visibility within the emerging gay and lesbian movements. Their efforts met resistance: the fight for recognition was framed in oppositional terms – gay versus straight – leaving no space for nuance.

During the AIDS crisis of the nineteen-eighties, bisexual men were portrayed as vectors of contagion between the two worlds. The media created the figure of the ‘bridge’ – a term that pathologized desire and legitimized mistrust. This stigma persists today, shaping how bisexuality is represented and discussed.

The middle erased. Eleni Bakst and Julia Shaw’s book Bi. The Hidden Culture, History and Science of Bisexuality

Sociologists use the expression bisexual erasure to describe how bisexual experiences are routinely dismissed or reinterpreted as temporary phases. Women identifying as bi are often hypersexualized; men are accused of confusion or cowardice.

Julia Shaw writes that bisexuals are «too gay for straight spaces and too straight for queer ones» – a paradox that isolates rather than connects. In 2023, Pew Research Center found that more than half of bisexual respondents avoid discussing their orientation at work, not because of fear but disbelief. Invisibility becomes self-defense.

The activist Eleni Bakst defines this dynamic as ‘the politics of credibility’: the demand to prove identity through consistency. Attraction, however, is not performance – it is presence. Yet both media and institutions continue to frame bisexuality as deviation rather than definition.

Representation of bisexuality in the movies: Pillion, Chasing Amy and Call Me by Your Name

Representation matters, but visibility alone does not guarantee understanding. In contemporary media, bisexuality is most often implied, rarely spoken. Its presence depends on visual suggestion – a lingering gaze, a line left unfinished – more than on language. This indirect mode of storytelling keeps desire aesthetic but not political.

In cinema, bisexual characters appear through ambiguity rather than declaration. In Pillion (2024), the film starring Alexander Skarsgård, speculation about the protagonist’s sexuality became part of the film’s marketing narrative. Neither the actor nor the director addressed the question, yet the visual coding – intimacy between men, an undefined romantic past with women – invited interpretation. This strategy is not new. From Chasing Amy (Kevin Smith, 1997) to Call Me by Your Name (Luca Guadagnino, 2017), attraction between genders becomes a metaphor for freedom, never an identity in itself.

Bisex culture in TV series: Euphoria, The White Lotus, A League of Their Own , Sex Education

Recent series have followed the same pattern. Euphoria and The White Lotus explore fluid relationships without naming bisexuality; Sex Education uses the character of Ola to signal openness but avoids terminology; A League of Their Own reframes historical queerness in coded gestures. GLAAD’s 2024 report shows that more than one third of LGBTQ+ characters on streaming platforms are described as bisexual or fluid, but less than fifteen percent use the term explicitly. Language is replaced by mood – a visual shorthand for inclusivity.

This narrative restraint reflects a cultural tension: bisexuality is accepted as theme but resisted as fact. Media scholar Julia Shaw notes that «ambiguous storytelling keeps audiences comfortable – you can read it if you want to». Ambiguity sells because it allows multiple interpretations, protecting mainstream comfort while appearing progressive. What disappears in this process is the lived reality of bisexual people, whose stories remain fragmented between desire and denial.

True representation would mean allowing bisexuality to exist without translation – neither as experiment nor as metaphor, but as ordinary human structure. Until then, the culture continues to frame the middle as mystery, not as presence.

Fluidity as avoidance. A 2024 GLAAD report on bisexuality

The rise of fluidity as a keyword marks a linguistic shift. The word promises freedom while avoiding commitment. Shaw argues that the popularity of ‘fluid’ allows people – and brands – to engage with non-heterosexual expression without confronting the stigma attached to ‘bisexual.’

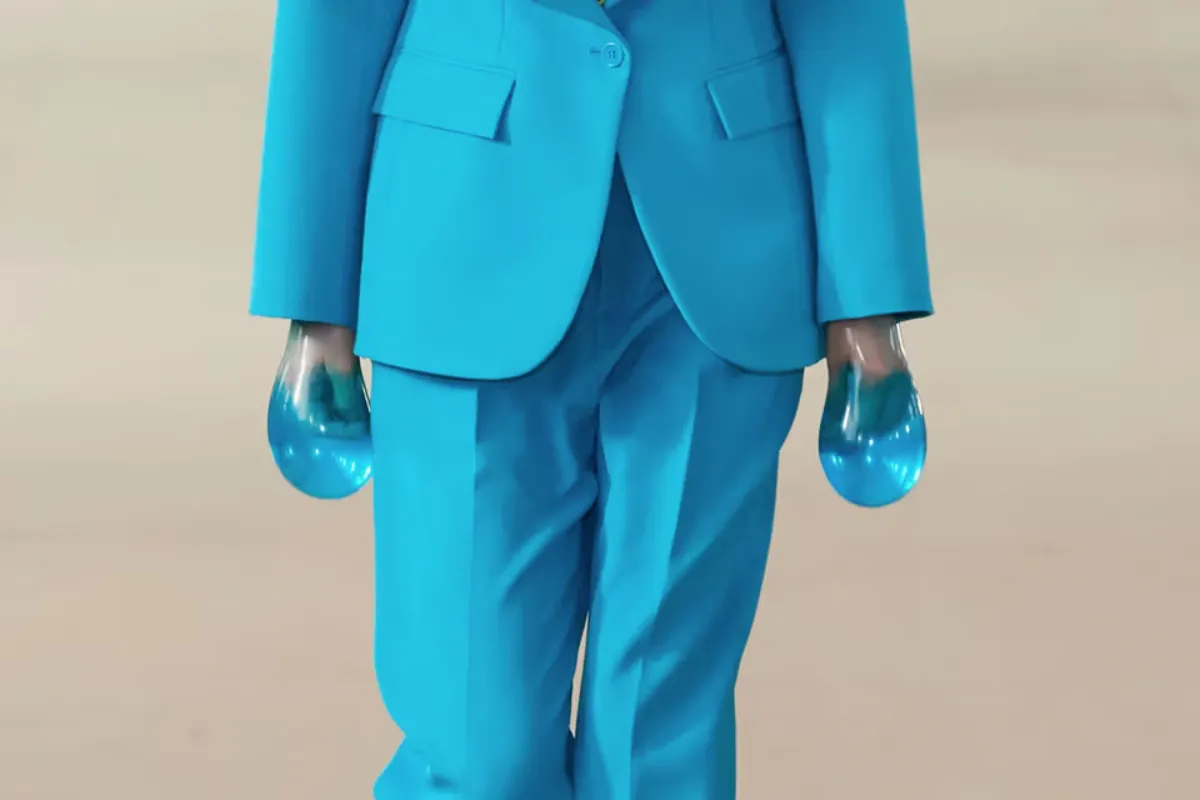

Fashion and entertainment industries have adopted this rhetoric. Campaigns from Gucci, Thierry Mugler, and Bottega Veneta present genderless desire as marketing language. The aesthetic of inclusion sells, but it rarely translates into representation behind the camera or within creative teams.

A 2024 GLAAD report shows that thirty-six percent of queer characters on television are labeled bisexual, yet only a small fraction exhibit long-term relationships with multiple genders. The category exists statistically but disappears narratively. Fluidity, in this context, functions as a euphemism – not as liberation.

A culture of coexistence – bi+ and the question whether bisexuality exist

To be bisexual is to live in the middle – not undecided, but plural. It is a refusal to define identity through opposition. This middle space, Shaw suggests, is inherently political: it challenges both binary thinking and capitalist marketing of identity.

Recognition, therefore, is not about visibility alone. It requires language, education, and empathy.

In recent years, younger activists have reclaimed the term bi+, an umbrella that includes pansexual, queer, and other multi-gender attractions. The movement’s goal is not to multiply labels, but to create vocabulary for experiences long reduced to silence.

The question bisexuality exist? is not rhetorical. It points to a cultural denial – a habit of ignoring complexity. Bisexuality exists every time categories fail. Its culture is one of coexistence, not confusion; continuity, not contradiction.

Bisexuality

Bisexuality describes attraction to more than one gender. The term emerged in medical discourse in the late nineteenth century and entered political language through LGBTQ+ activism in the nineteen-seventies. Today, bisexual people represent the largest subgroup within the queer community.