Why we keep falling for Elmgreen & Dragset

As their work enters Casa Italia at Triennale Milano, we return to our interview on space, storytelling, and the art of dressing the white cube

Lampoon Editorial Team: an updated introduction

Elmgreen & Dragset at Casa Italia Milano Cortina 2026: The Sky Above Rome at Triennale Milano

Elmgreen & Dragset are among the artists featured at Casa Italia Milano Cortina 2026, hosted at Triennale Milano.

With The Sky Above Rome (2026), in stainless steel and oil paint, the duo introduces a work that places the viewer at the center of the experience. The reflective surface activates awareness: of one’s body, of spatial coordinates, of the act of looking. The reference to the sky of Rome evokes an iconic horizon of Italian art history, turning a symbolic landscape into a conceptual device.

Within the broader framework conceived by CONI for the Milano Cortina 2026 Winter Olympic Games, the project unfolds under the theme MUSA. Casa Italia operates as a cultural platform across Milan, Livigno, and Cortina, where art, hospitality, and Olympic values intersect. In this context, Elmgreen & Dragset contribute a work that interrogates perception and identity while aligning with the narrative of Italy as a source of imagination, heritage, and creative continuity.

Elmgreen & Dragset: from Copenhagen’s queer scene to international fine art

Words Daria Miricola

Images Spyros Rennt, first released on Lampoon ISSUE 30

Everything happened in Copenhagen in the early nineties. We met one night at the After Dark club. Michael wrote poetry and Ingar came from the performance theater scene. We were working in the cultural world and then started collaborating, mixing our backgrounds and doing art performances. In Copenhagen, there was an open scene at the time. It was like a generational shift where we learned a lot from our peers.

There was freedom, because institutions in Denmark were quite conservative. We would never get an invitation to show our work there. We didn’t have to live up to anything, to please anyone, or to get a position to be loved. We could do what we wanted with our friends. We were immersed in queer and identity studies in the US, which had just arrived in Scandinavia.

We met Felix Gonzalez-Torres at some point. He was already sick, but we were inspired by our conversations with him. We met Connie Butler, now director of MoMA PS1 in New York. She looked at our first artworks and helped us formulate thoughts around them. We weren’t fully aware of what we were doing. We acted from intuition.

Dressing the white cube in drag: transforming museum and gallery spaces

We didn’t come from the art world. We didn’t go to art academies. We were surprised to experience that most places that show art are standardized in how they look. It didn’t matter if we went to Asia, the United States, or Europe — all the white cubes looked more alike than McDonald’s.

At the Zurich Kunsthalle the display looked like an art fair. We thought: maybe we can transform it into a different exhibition environment. The idea at the basis of our art production is to use museum or gallery spaces as our canvas. This is our raw material.

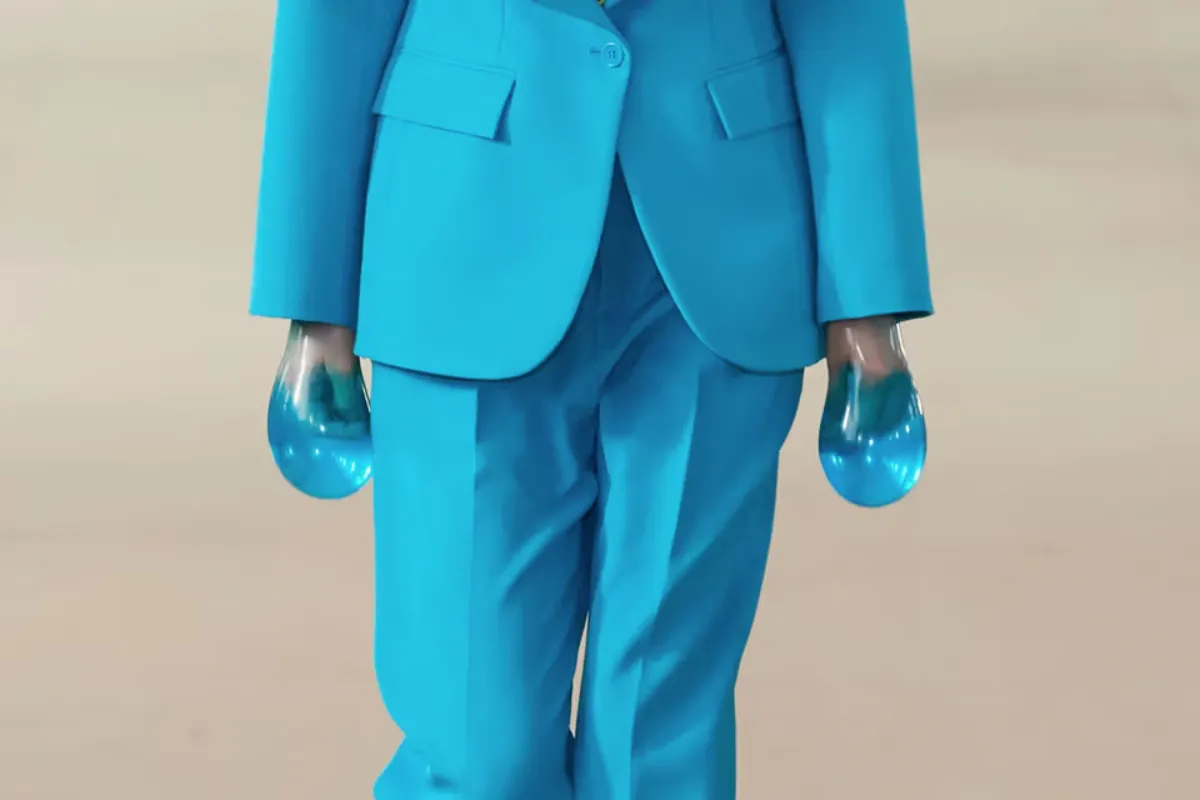

Today we may not break holes in walls or repaint entire galleries as often, but we still “dress the white cube up in drag.” We make it look like something else for the duration of the exhibition. It can resemble a home, a public swimming pool, a hospital room, or an airport.

In 12 Hours of White Paint (1997), we attacked the gallery space, painting it continuously from noon until midnight. We washed it down with a water hose in between, turning the white cube into a mess. In Untitled (1996), we unraveled long knitted skirts in slow motion to construct a softer masculine image within the grungy 1990s context.

We are soft and neurotic. We work on polishing and coating details. We don’t leave surfaces rough. They are smooth — though smooth can also be rough. We hang objects upside down or push them into the ground. We twist situations.

Elmgreen & Dragset in Milan: Short Cut, Useless Bodies and institutional dialogue

Over the last twenty years, we have been working in Milan. In 2003, Short Cut occupied Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II: a Fiat Uno and caravan rising from the marble floor. It questioned contemporary travel and the global tourism system. International media attention turned it into a traveling work.

In 2022, we collaborated with Fondazione Prada on Useless Bodies, a monographic exhibition conceived in dialogue with the institution’s research into the human body — its meanings, its social coding, its assigned value.

Earlier, at MASSIMODECARLO Gallery, in How Are You Today?, we cut a hole in the ceiling of the exhibition space. Visitors climbed a ladder and emerged into the kitchen of the woman living upstairs. The project addressed the lack of relationship between the gallery and its surrounding working-class neighborhood.

Berlin studio: industrial architecture and production processes

Berlin remains our base. Our studio is located in Neukölln inside a 1920s water pumping station, 10,000 square feet. The exterior is industrial brick. The interior is a bright open space divided between ground floor and mezzanine.

Around sixteen people work with us. Some focus on graphic design and image production. Others develop computer renderings. Workshop assistants prepare and model figurative sculptures. We do live casts. We scan people and process data for 3D printing. We travel to bronze and steel foundries, and to our marble carver in Carrara, who helps transform prototypes into final materials. Each day is different.

Powerless Structures and performative sculpture

One of our first sculptures was Powerless Structures, Fig. 11 (1997) at the Louisiana Museum in Denmark: a diving board penetrating a panoramic window overlooking the sea.

We had been invited late to a group exhibition and there was no room left for performance. The only available space was the panoramic viewing room, usually not used for art. We asked for it and received it.

The diving board was humorous, yet carried sadness. An object can become performative, almost human. That was one of the first times we noticed how deeply audiences engaged with sculpture.

The Collectors, Whitechapel Pool and narrative environments

At the 2009 Venice Biennale, we transformed the Nordic and Danish pavilions into two domestic interiors for The Collectors. Visitors walked through furnished homes, speculating about the lives of fictional inhabitants. Storytelling became central to our installations.

With The Whitechapel Pool (2018), visitors believed the swimming pool had always existed beneath the Whitechapel Gallery. Some claimed childhood memories of swimming there, even though it never existed. Fiction merged with institutional memory.

Prada Marfa and viral contemporary art

Prada Marfa (2005) was conceived as a remote installation in Texas, three hours from the nearest airport. Thirty people attended the opening. Through Instagram, The Simpsons, Beyoncé, and Gossip Girl, the work became globally recognizable. Many feel familiar with it without ever visiting.

Digital culture reshaped its reception.

Swimming pools in contemporary art: metaphor, queer imagery and middle-class dream

The swimming pool carries layered meanings. It replicates nature, an attempt to control it. Public pools allow near-naked bodies to coexist in a regulated environment. In queer culture, the pool is iconic — visible in artists like David Hockney.

The pool also symbolizes the American middle-class dream of success and wealth. In Van Gogh’s Ear (2016), installed at Rockefeller Plaza, the swimming pool is turned on its side.

Fine art and swimming pools seem distant categories. The pool is banal, simple, pleasurable. Its apparent lack of art status makes it productive.

Public sculpture vs gallery exhibitions: audience dynamics

There is a difference between gallery exhibitions and public sculpture. Museum visitors choose to enter an art space. Public art confronts people who did not request it.

In public space, viewers bring unpredictable emotional states. Someone might have won the lottery or lost their job. That context matters. When we installed Van Gogh’s Ear, people slowed their cars, climbed into the sculpture, photographed themselves.

At Rockefeller Plaza, competition for attention is constant. A bold gesture can still trigger fearless interaction.